Cataract surgeons have been trying to avoid, or at least minimize, off-target first-eye outcomes for decades. To this day, however, none can point to textbook solutions that work on every patient. “Things are different today than they were 10 to 15 years ago, when we didn’t have multifocals or the femtosecond laser,” says Doug Grayson, MD, a cataract and glaucoma surgeon at Omni Ophthalmic Management Consultants, a multi-practice group headquartered in Iselin, New Jersey. “We didn’t use PRK for postop touch-ups, and patients weren’t paying for lenses. Therefore, patients didn’t have the same level of precise expectations.” Dr. Grayson and other surgeons also point to an evolving environment—highlighted by new technology, lens-calculation formulas and insights on pathology—that continues to raise the bar surgeons need to meet.

“We’re trying to predict on an order of millimeters how the lens implant will settle within the eye’s capsular bag,” says Jesse Richman, MD, a cataract surgeon at the Kremer Eye Center in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. “If the postoperative effective lens position is a smidge to the left, you could have more of a myopic result than you intended. If you go a smidge to the right, a hyperopic result. It’s so miniscule, but that’s what can make a difference that’ll produce a result that you and your patient don’t want.”

What are your first steps when confronted by a refractive surprise? These and other surgeons may help you consider new ones by sharing their strategies in this report.

Strategies to Consider

Kathryn M. Hatch, MD, director of the refractive surgery service at Massachusetts Eye & Ear, and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, says she avoids rushing to conclusions about a refractive surprise.

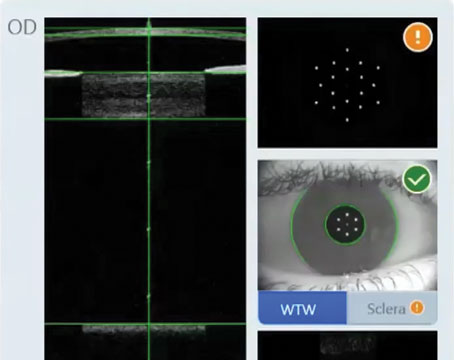

“When the eye’s healed, then you can tell if you have a true refractive surprise,” she says. “You want to make sure your biometry and other preoperative measurements were ideal. If you don’t have good biometry—if the eye’s dry or some other issue is a factor—that may be affecting your outcome.”

|

|

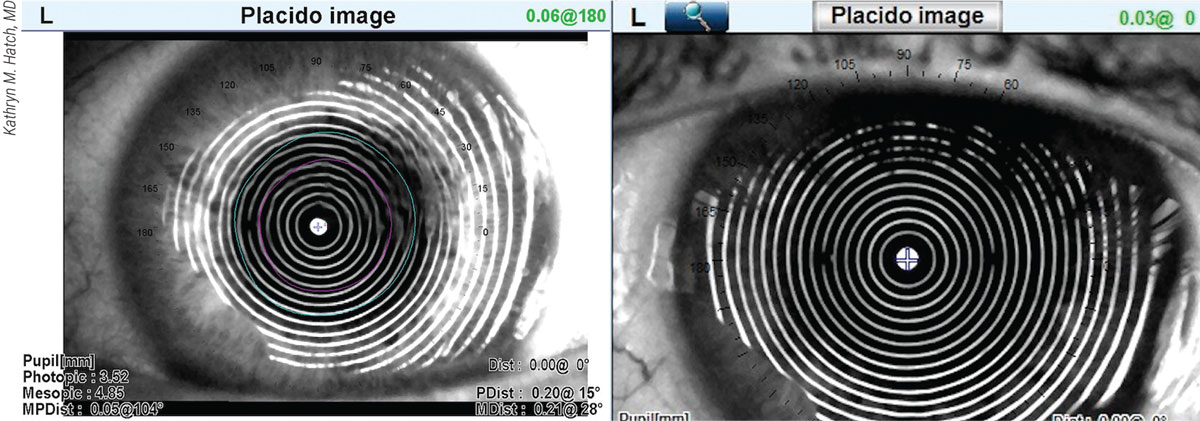

Figure 1. The placido image of an OPD-Scan III shown on the left reveals the likely cause of a post-cataract-surgery patient’s refractive surprise—the wavy rings of dry eye, compared to the normal presentation of rings shown in the image to the right. |

Dr. Hatch also revisits the formula she’s used, considers the implications of long and short eyes and determines if previous refractive surgery might be affecting her results. “I also look for consistency,” she says. “I want to confirm that my IOLMaster 700 measurements reflect tight numbers, rather than, say, three different axes for astigmatism. All of my patients undergo corneal topography and an OPD-III scan. The mire rings on the scan can confirm consistent keratometry values and tell me, for example, if dry eye is a factor, reflected in spots on the rings.” (See Figure 1.)

Dr. Hatch also relies on intraoperative aberrometry, using the Optiwave Refractive Analysis System (Alcon), to safeguard against surprises. “ORA is important,” she says. “Not only does it provide extra measurements I can compare to preop measurements while the patient’s still phakic on the table, it offers real-time measurements that include the incision and everything else that I’ve done to the eye up to that point.”

In the event of a refractive surprise, Dr. Hatch mines her data and typically identifies one revealing measurement that influences her approach to the second eye. “If you’re trying to target a different distance but the patient ends up somewhat nearsighted, there may be some advantages to proceeding with the second eye,” she says. “I tell the patient that we can go back and do something with the first eye, if that becomes necessary.”

She establishes realistic preop expectations for her patient, especially if she’ll be working on a post-refractive-surgery eye or implanting a premium IOL. “It’s important to keep in mind that patients receiving premium lenses want near correction,” she notes. “After standard cataract surgery, a refractive surprise may not be a big deal to the patient who expects to wear glasses anyway.”

Customized Lens Constants

Like most surgeons, Dr. Hatch makes a patient-specific lens-constant adjustment or a formula-specific adjustment. “How I proceed depends on the eye,” she says. “We use our formula to determine where we think the effective lens position will be, but sometimes it doesn’t end up where we expect it to be. Often, that’s why we get refractive surprises. We also have outliers who don’t necessarily follow the formula. They might end up minus when I was targeting them at plano. I may target the next eye a little more plus so I can get them closer to plano with the second eye. Highly myopic patients with long eyes will typically end up better off a little nearsighted, as opposed to a patient who’s extremely farsighted who won’t like that adjustment. So your response is going to be determined by the type of surprise and patient.”

For patients who’ve undergone RK or high-myopic/high-hyperopic LASIK, she notes that the eyes tend to be highly aberrated and extra challenging. “They may take longer to recover, and surgery sometimes results in a refractive surprise,” she says. “Unfortunately, a lot of these patients are used to having really good vision, so they have very high expectations for their postop vision.”

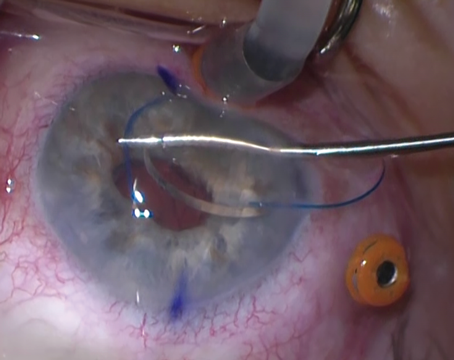

When the First Lens Must Go

Dr. Grayson says he almost always feels compelled to exchange the lens in the first eye after a refractive surprise. “I think the more modern viewpoint is not to necessarily deal with the second eye differently than the first eye, but to deal with the first eye to get it optimal, meeting the patient’s expectations,” he says. “When a patient isn’t completely happy with the first eye, I’ve found that it’s very difficult to tell that patient, ‘Okay. We’ll just take care of that with the second eye.”

|

|

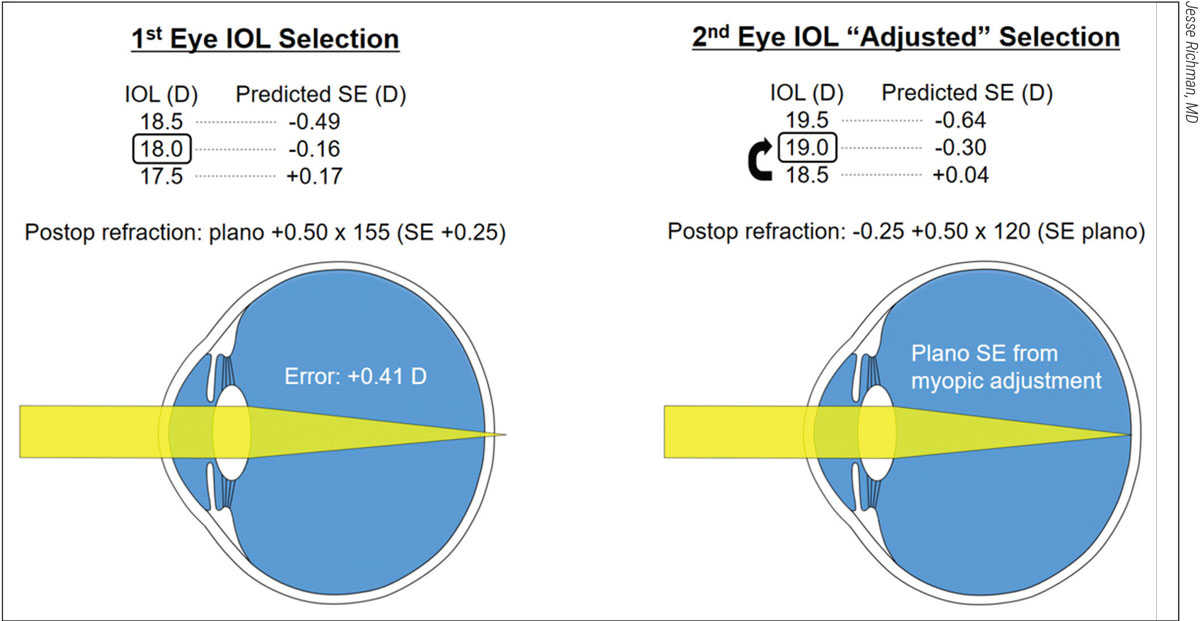

Figure 2. For this patient’s first eye (left), an 18-D IOL was selected, based on a formula that predicted postop vision with a spherical equivalent of -0.16. As shown, however, the postop refraction revealed a hyperopic error of +0.41 D. To compensate for the error, an 19-D IOL was selected for the second eye, despite the prediction by the formula that an 18.5-D lens would get the patient closer to plano. This adjustment worked, resulting in a postop SE of plano. |

Some surgeons try to avoid lens exchanges and take simple problem-solving approaches. Dr. Richman describes a recent example in his practice involving a 77-year-old male with a 3+ cataract and BCVA of 20/100. “On the IOLMaster 700, an IOL with a power of 18 D appeared to be the best option for this patient,” he explains. (See Figure 2.) “According to the formula I used, I expected a result of -0.16, or as close to 20/20 as I could get. If I had put in a 19-D lens and the formula was correct, the patient would’ve ended up with -0.81, meaning more near vision but distance vision that wasn’t as sharp.”

After removing the cataract from the right eye without complications, he discovered the following manifest refraction: +0.50 -0.50 x 65 (SE +0.25). “With a spherical equivalent of +0.25, I’d missed by +0.41 D,” he notes. “Some surgeons facing this type of error might say, ‘Let me take the full amount by which I was off and apply it as a fudge factor, or personalized A-constant, to the other eye,’ concluding that they’ll be off by the same amount in the second eye if they don’t use this fudge factor. However, most of the peer-reviewed papers on this type of postoperative challenge recommend that you correct for about half of your error.”

With this guideline in mind, he implanted a 19-D IOL in his patient’s left eye, even though his IOLMaster 700 reading on that eye suggested he could implant an 18.5-D lens to achieve a +0.04 D result. “However, I’d missed by +0.41 D on the right eye, and the IOLMaster was telling me a 19-D lens would get me to -0.30, which meant I would get pretty close to the same error and, therefore, I should get close to zero using the 19-D lens,” explains Dr. Richman. The postop manifest refraction—proving him right—was +0.25 -0.50 x 30 (SE plano).

“This is just how I do it,” he says. “Because lenses come in half-diopter increments, sometimes you just have to decide what makes the most sense.”

Systematic Approaches

Thomas Chi, MD, a Northeast Ohio surgeon at Midwest Vision Partners in Medina, Ohio, categorizes refractive surprise patients as follows:

- truly unhappy;

- slightly disappointed but potentially accepting; and

- indifferent and seemingly satisfied.

“The truly unhappy patient may require surgical intervention, such as corneal refractive surgery (LASIK, PRK), an IOL exchange or a piggyback IOL,” he says.

He groups the potential causes of surprise into three categories:

- An error could have affected data input or communications among surgical team members.

- Ocular conditions, such as corneal surface disease (including dry-eye disease, anterior basement membrane disease, superficial punctate keratitis and keratoconus), retinal conditions (such as epiretinal membrane and staphylomas) or compromised zonular integrity (pseudoexfoliation) could be implicated. “Ocular surface conditions need to be treated before taking any repeat measurements of the second eye,” he adds.

- Imprecise biometry and keratometry measurements must be considered. “We’ve used many of the biometry checklists (axial length, keratometry, etc.) of Warren Hill, MD, and others to confirm that certain biometry data fall within a certain range and in line with the other eye,” he explains. “We limit the number of staff members who perform these measurements to avoid variabilities.”

Since optimizing their A-constants with IOLMaster 700’s biometry, Dr. Chi says he and his colleagues lean toward using patient-based adjustments with the same surgical technique—while striving to achieve the following during the second surgery:

- performing a capsulorhexis of 5 to 5.5 mm to enable a sufficient circumference overlapping the rhexis with a 6-mm optic, after completion of irrigation and wound hydration; and

- minimizing zonular stress, using effective hydrodissection and/or delamination while employing a phaco tilt technique or femtosecond laser lens fragmentation.

If the target is an emmetropic result and a patient ends up myopic (-0.75 to -1.25 D) or if the target is slight myopia and the patient ends up emmetropic, Dr. Chi says he places an appropriately powered contact lens over the first eye and shows the patient how the intended result would appear.

“Sometimes the patient changes his or her mind and prefers to leave the unintended vision as it is,” says Dr. Chi. “When it comes to refractive surprises, as always, what works can vary widely.”

Dr. Hatch is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision. None of the other interviewed surgeons have relationships with makers of products mentioned in this article.