Patient unhappiness inevitably comes with the premium lens territory at one point or another, but there are a number of steps surgeons can take both preoperatively and postoperatively to reduce the likelihood of these trying scenarios. “You have to have a mechanism for dealing with the unhappy patient once they’re on the other side of surgery,” says Kevin Miller, MD, a professor of clinical ophthalmology and the Kolokotrones Chair in Ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “Before surgery, it’s a matter of explaining what we can do.”

Here, veteran cataract surgeons share their top tips and techniques for dealing with unhappy premium lens patients and offer pearls for minimizing unwanted outcomes.

Keep Calm & Carry On

“It’s a different thing when you’re dealing with unhappy premium patients and they’re your own patient versus one who’s been referred to you versus one who’s come to you on their own for a second opinion,” says Steven G. Safran, MD, who’s in private practice in Lawrenceville, New Jersey. “The dynamics of these interactions are very different. Usually, patients are less angry when they’re referred to me by another doctor. The patient is still following that doctor’s plan, still on their team. Most of these patients’ complaints are pretty reasonable: negative dysphotopsias, ocular surface issues.

“When a patient seeks me out on their own, very often they’ve broken away from their doctor and have lost faith,” he continues. “They come in, and they’re typically angrier. They want you to validate their misery, and it’s very important not to do that. Instead, get to the bottom of the patient’s concern. Why are they unhappy? Do they have realistic expectations? Is it a lens-related problem? A residual refractive error? An anatomical problem? Are they upset about the money they spent? Figure out where the patient wants to go and how to get them there.”

When your own patient complains, it can be difficult not to take it personally. “Becoming defensive and deflecting the blame is a common first reaction,” says Dr. Miller, “but it’s important to step back and focus on next steps. These patients are frustrated with the situation and may be a little bit afraid of what their life is going to be like in the future. Listen to the patient, let them know you understand, and repeat their concerns back to them, as any psychologist would do. Let the patient know that there’s a plan in place and that you’ll stick with them. The worst thing you can do is abandon the patient.”

Dr. Miller says that at this point, it may not be possible to achieve the outcome the patient is looking for, but you can promise to do your best. “Nobody can promise perfection, and people realize that’s the way life is,” he says. “Patients just don’t want to be kicked to the curb.”

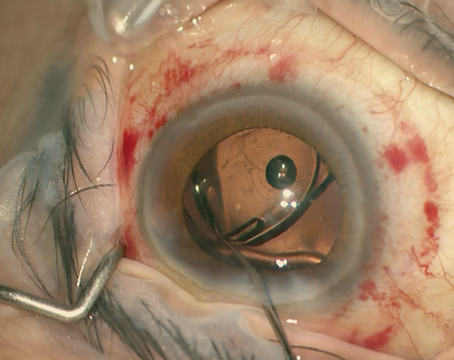

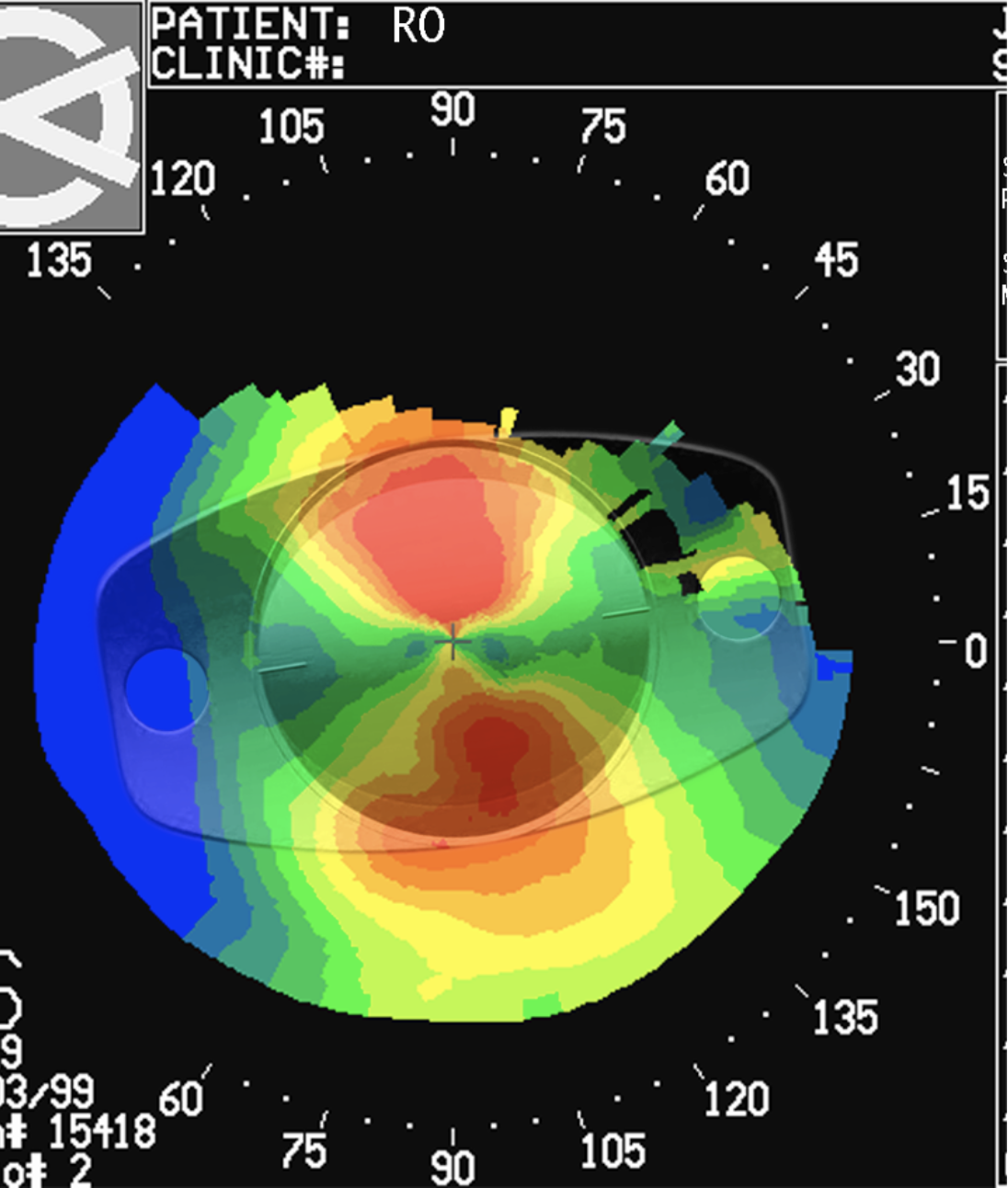

|

| Toric IOLs may end up off axis for a number of reasons, including incorrect positioning at the time of surgery, incorrect calculation of the postop steep axis or rotation after implantation. (Courtesy Kevin Miller, MD) |

No Magic Bullets

Unrealistic expectations about what’s achievable with surgery or intraocular lens technology are a common reason for patient unhappiness. “There’s a lot of hype about premium lenses, but everything in the cataract world is a trade-off or compromise,” Dr. Miller says. “You give up something to get something. For instance, the patient may be giving up the ability to look at lights at night and not see halos in order to have a multifocal lens. We have to counsel patients that halos are just one of the realities of multifocals. That said, most patients who get multifocals are quite happy with them and would choose a multifocal again if given the opportunity.”

Dr. Safran points out that most premium lenses have worse quality of vision than monofocals. “Premium lenses are often sold as upgrades, but patients need to understand they’re not better or upgraded lenses,” he says. “There’s no lens that does everything perfectly. I explain to patients that the lens they may be unhappy with would make a different patient very happy. It’s a matter of making the right match.”

“I make sure to tell all the multifocal patients ahead of time that I’m not going to get them out of glasses,” Dr. Miller says, adding that he often has to remind unhappy patients of this fact. “Multifocals won’t eliminate the need for glasses, but they can reduce dependence on glasses.”

Surgeons say it’s important to set up patients’ expectations for the early postoperative period as well. “Patients are quite patient if they know that they’re not going to be stuck with whatever it is they’re experiencing at the moment and that you have a plan,” Dr. Miller points out.

For early postoperative unhappiness, complaints usually stem from foreign body sensation from the incision and occasionally some corneal edema. “Reading vision seems to be particularly affected in multifocal patients when there’s any central corneal edema,” Dr. Miller says. “I tell all the multifocal patients that the day after surgery they’ll notice that their distance vision will come in first. That will sharpen first and then a few days later their reading vision will start to come in.

“I also tell them not to panic if their reading vision isn’t that good with just one eye done,” he adds. “Multifocals split light, so the contrast isn’t going to be as good as their other eye, which hasn’t been operated on yet. I tell them that once their other eye is done, the two eyes will work together and then they’ll see the increase in contrast that occurs with binocularity and really appreciate the reading vision.”

“When I see the patient on day one, it’s too early to assess what the refractive surprise is, if there is one,” says Sumitra Khandelwal, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine, Cullen Eye Institute, and medical director of the Lions Eye Bank of Texas in Houston. “Waiting to refract will also give the patient time to experience their new vision. When you bring them back, if they’re happy, that’s great that the outcome is working for them. If they’re still unhappy, we’ll look closer.”

“In the postop period, let patients know that corneal swelling is normal, and that vision will improve as that settles down,” Dr. Miller says. “If they’re concerned that they’re going to have a refractive error, make sure to tell them that you have a plan for that, whether that’s glasses or LASIK/PRK enhancements.”

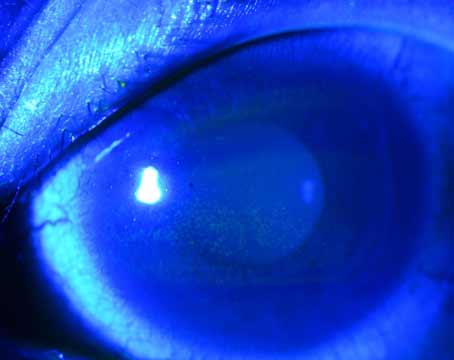

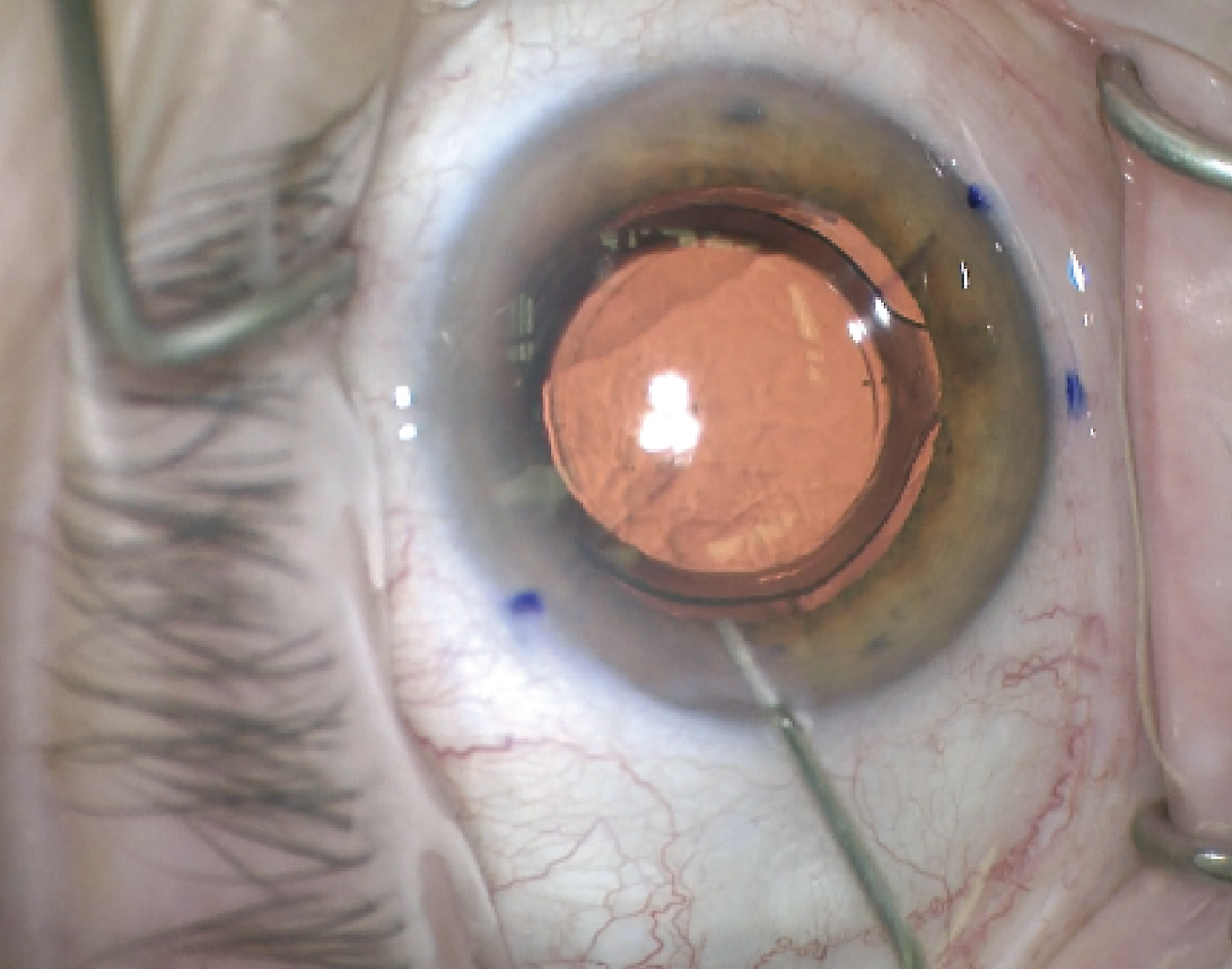

|

| Here, a surgeon aligns the toric lens with the steep axis of postop astigmatism. (Courtesy Kevin Miller, MD) |

Setting Up for Success

Minimizing the chances for patient unhappiness begins on the front end. Catching potential issues early on will guide the discussion with the patient, helping to set realistic expectations.

“We rely heavily on Placido-disc or Scheimpflug imaging like Pentacam or Galilei to make sure the topography is nice and smooth,” says James Loden, MD, who’s in private practice at Loden Vision Center in Nashville. “One of the biggest things is making sure the patient doesn’t have chronic dryness or irregular astigmatism. Then, we also look at an OCT of the macula in every potential premium patient. We don’t like getting bushwhacked by unrecognized epiretinal membranes, lamellar macular holes, partial macular holes or anything that could cause potential distortion of vision. If the patient is paying $5,000 for a premium IOL, they don’t expect you to miss a diagnosis and tell them after the fact that there’s an issue. They want to know ahead of time, and it’s much more effective to just not schedule the patient for a premium service than to have to refund them and go through that process afterwards.”

Dr. Khandelwal says that meticulous preoperative biometry and keratometry will help avoid refractive surprises after cataract surgery. “We never want to use just one formula for refractive cataract patients,” she explains. “We look at several formulas. The most important thing is to make sure you have good data going in, that your keratometry, axial length and other measurements are all reliable to avoid refractive error.

“Secondly, really assess and address astigmatism, especially against-the-rule astigmatism,” she continues. “It’s very easy to dismiss small amounts of astigmatism and implant a non-toric premium lens, but if you’re going to end up leaving residual, against-the-rule astigmatism, you may want to go ahead and take the extra step to put in a toric presbyopia-correcting lens. It certainly isn’t costing the patient any more money or your practice any more money, but it can really affect the outcome. Try to minimize the astigmatism to less than 0.5 D.”

Anatomic Issues

Diffractive lens optics have very complex wavefronts that are easily affected by ocular pathology and astigmatism. “Multifocal lenses have diffractive steps that create in-phase and out-of-phase light patterns,” Dr. Safran explains. “Anything that scatters light, such as dry eye or corneal guttata, will disrupt the quality of vision with these lenses.”

Ocular pathology that goes unidentified preoperatively or crops up postoperatively is often a cause for patient unhappiness. Here are some issues to watch out for:

• Dry eye. “Dry eye is very common and needs to be addressed before surgery,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “Put the patient on a regimen that works for them to improve their ocular surface and be sure to counsel the patient that they may need to remain on this regimen for life in order to get the best quality of vision from their lenses. It’s very important to set the expectation that something else is going to affect their vision.

“Postoperatively, if they develop ocular surface disease, it’s important to determine whether it’s aqueous deficiency, evaporative dry eye or a combination of the two to tailor treatment,” she explains.

Punctal plugs, artificial tears, Tyrvaya nasal spray, Restasis, Xiidra, steroids and immunomodulators are a few options. “Thermal expression can be done in the office to help patient outcomes,” she says. “Ideally, you should diagnose and treat them before surgery.”

• Anterior basement membrane dystrophy. Like dry eye, one of the challenges with ABMD is that it worsens after cataract surgery. “Patients who didn’t know they had ABMD are going to be very unhappy if it worsens after surgery,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “For the best outcome, you may want to treat the ABMD with a superficial keratectomy or medical management ahead of time.”

• Lid problems. Some patients complain of tearing after cataract surgery. Dr. Khandelwal says to look carefully at the lids to ensure patients don’t have mild ptosis, inferior lagophthalmos or conjunctivochalasis. “Some of those can worsen a bit after doing any procedure that opens up the eyelid,” she notes.

• Irregular astigmatism. “Irregular astigmatism is a pain,” Dr. Miller says. “Most patients don’t want to wear rigid contact lenses to hide the irregularity. Sometimes we can put them on miotic drops to pinhole the pupil, so they don’t see as much of their irregular cornea, but many patients don’t want to put drops in every single day to reduce their pupil size because the surgeon didn’t identify their irregularity ahead of time.”

• Prior RK or LASIK. “I’d discourage multifocal lenses in any patient with prior radial keratotomy,” Dr. Loden says. “These eyes have a tendency to be very unpredictable and the vision fluctuates a lot. They also tend to have a lot of higher order aberrations that interact with the multifocal lens. I’d be cautious in post-LASIK eyes as well. If the patient has a lot of spherical aberration or any residual astigmatism or de-centered ablations, definitely don’t put a multifocal lens in. These patients will be difficult to satisfy.”

• Retinal pathology. Lamellar holes, retinitis pigmentosa, obvious diabetic retinopathy, anything beyond mild macular degeneration and epiretinal membranes involving the fovea will result in poor vision quality with premium lenses. “I repeat the OCT of the macula because sometimes there’s subtle macular edema or subtle worsening of an epiretinal membrane that you want to make sure to catch,” Dr. Khandelwal says.

• Capsular wrinkles. “Capsular wrinkles or opacities are very common causes of patient unhappiness,” Dr. Miller says. “When the refractive error is good and almost no glasses prescription is needed, and the patient still isn’t happy, most of the time there’s some wrinkling in the capsule behind the lens implant. I tell those patients that the wrinkles may pull out over time or may get worse over time, and either way we have to wait until the capsule locks on and is holding the lens implant securely before we can address it. Bring the patient back six months later to reassess and then you may ultimately perform a laser capsulotomy.”

• Neuralgia. Many patients have subtle neuralgias from the incision. “Anytime you make a cut in the cornea, you’re cutting through nerve endings, and those nerve endings don’t always regenerate normally,” Dr. Miller says. “So, patients can get a kind of funny feeling at the incision. Sometimes it’s just a matter of hand-holding the patient through the recovery phase, which may take several months.”

• Neurological problems. In particular cases, if there’s any question of atrophy of the nerve or glaucoma, Dr. Loden looks at the nerve as well to make sure there’s nothing neurological affecting the outcome.

• Loose zonules. “This is an example of what’s called a ‘potentially problematic condition,’ where you could probably get away with it but down the road, it may not go so well,” says Dr. Miller. “A patient with loose zonules and pseudoexfoliation, for example, may have a perfectly centered lens for a few years but over time the lens may start to decenter and so will the quality of vision. In this case, it’d be wiser to go with a monofocal lens, so that if the lens does decenter down the road, the vision won’t degrade nearly as much as with a multifocal, which is heavily dependent on centration.”

• Interocular pathology. Eye misalignment, for example, may point to a poor premium candidate from the outset. “A cataract patient with good potential vision, no ocular pathology but eye misalignment might have great distance vision in both eyes or multifocality but when they use their eyes together they’ll have double vision, requiring prism glasses,” Dr. Miller says. “Since they’ll need glasses anyway, why not just give them progressives with prisms?”

When It’s the Lens

It’s important to distinguish anatomic issues from lens-related issues when figuring out why a premium patient is unhappy. “If a patient has a multifocal and they’re unhappy with glare, halos and their quality of vision, and they say to me, ‘I don’t mind wearing glasses,’ then obviously, the multifocal wasn’t the best lens choice for the patient,” Dr. Safran explains. “Then you have to look at the risks associated with a lens exchange.

“Each lens has its own little bag of issues that you’d expect to hear,” he continues. “If a patient comes to me with a PanOptix, and they’re complaining of glare and halos, those are reasonable things for someone with a trifocal to experience. If a patient has a Symfony EDOF, and they’re complaining about starbursts, that’s also reasonable. If, on the other hand, they’re complaining about quality of vision with the Symfony, then that’s unlikely to be a lens-related issue, so it may be something else.”

Dr. Loden says his practice uses the Visiometrics ocular scatter index to assess the lens’s modulation transfer function. “Much of the time you’ll find that these eyes are highly aberrated and the quality of vision that the patient is reporting is indeed very poor,” he says. “If you don’t have a pathologic reason for why that’s occurring, it’s probably the optic of the multifocal lens. What we found is that for many of these patients, simply explanting the multifocal and exchanging it with a monofocal will dramatically improve the ocular scatter index and modulation transfer function.”

Refractive and Lens-based Procedures

“The number one reason for premium patient unhappiness is refractive error,” Dr. Loden says. “If the patient comes in saying they’re unhappy with the quality of their vision, it’s often undiagnosed refractive error—even as little as a quarter diopter.

“The average multifocal or trifocal patient will lose one line of vision for every quarter diopter of residual astigmatism,” he explains. “So, you may have a patient who’s +0.25 or -0.75, the spherical equivalent of that is really low, ±0.5 D, but the patient complains vociferously that they’re unhappy with their vision. The issue is that many doctors ignore these very small amounts of astigmatism, but some patients just aren’t happy with that, and the only thing that can treat that small amount is PRK or LASIK touch-up.”

Dr. Loden adds that though his practice discourages self-referral consults, in those instances he performs rigorous testing that includes iDesign. “We do a manifest refraction based on our iDesign measurements, in addition to a comprehensive exam,” he says.

Dr. Safran says that about two-thirds to three-quarters of the unhappy premium patients referred to him didn’t have a good refractive outcome. “Nobody is going to be happy with a multifocal or EDOF lens where the refractive outcome is off,” he says. “Autorefractors aren’t always accurate with EDOFs. If the technician follows the autorefractor and puts that data into the phoropter, the patient’s refraction may be off, creating a lot of problems. Very often I see a patient who’s unhappy with their multifocal lens, and they’re actually a +1 D refractive error rather than plano like the doctor thought. There’s your answer to the unhappiness right there.”

Dr. Khandelwal agrees that postoperative refraction must be done carefully in patients who had EDOF lenses implanted. “It’s easy to say, ‘Hey, they’re 20/20. They should be happy.’ But it’s important to take the extra step to have your technician refract,” she says. “Sometimes a little bit of astigmatism or plus power wasn’t captured. Put a soft contact lens on the patient and correct some of that refractive error. If they’re really happy with the outcome—I usually give it a bit of time and then repeat the refraction to make sure it’s stable—then you can do a corneal refractive procedure on them later. That’s one way to handle refractive errors.”

“If it turns out that the patient has a refractive error, an easy option is to give the patient some glasses,” Dr. Miller says. “Contacts are another option, but almost no one in the cataract age range wants to wear contacts because oftentimes their eyes are a little dry and it’s just a hassle.

“Refractive options include PRK and LASIK,” he continues. “They each have their pluses and minuses. PRK is kind of a painful procedure to go through, and it takes the older patients two to three months to settle down. It’s not terribly predictable for small corrections. LASIK has a faster recovery, but in my experience there’s a little more tendency for it to produce dry eye. That said, if you have to do an enhancement, it’s much easier to do a LASIK enhancement than PRK. PRK requires scraping the cornea, which is uncomfortable in the recovery phase. SMILE isn’t an option for enhancing cataract surgery because the corrections we’re doing are smaller on average than what SMILE treats.

“Sometimes relaxing incisions are the best option,” Dr. Miller notes. “They can be performed in patients with some mixed astigmatism, or maybe the spherical equivalent refractive error is zero or close to zero and the patient has some cylinder, and the status of capsular bag isn’t important.

“For residual astigmatism after toric IOLs, if the capsular bag is intact and the patient isn’t too far out from cataract surgery, toric IOL repositioning is a good option if the spherical equivalent refractive error is within 0.5 D of target,” he continues. “If it’s greater than 0.5 D, a toric IOL exchange may be the best approach.”

Dr. Safran says he’s quick to do a lens exchange since he does about four or five per week. “I’m very comfortable doing lens exchange,” he says. “One thing you don’t want to do is dig a deeper hole and make it harder to deal with the patient’s problems by say, doing LASIK over the lens they have. If they’re not happy with the lens, I’d rather take it out before I double down. Sometimes the lens is tilted or dislocated, and then a surgeon does LASIK over it, compensating the cornea for a problem with the lens.”

“If you think the patient isn’t tolerating the lens because of dysphotopsias, glare, halo or streaking at nighttime, avoid doing a posterior capsulotomy until you’re absolutely sure that the lens is going to stay in the eye forever,” Dr. Khandelwal advises. “It can certainly be done, but it’s going to make your life much more complicated if the patient has an open posterior capsule.”

Pricing Additional Services

If the patient requires an IOL exchange, be sure to work out in your practice how you’ll address the return to the operating room, says Dr. Khandelwal. “A corneal refractive procedure such as LASIK or PRK is a bit easier when it comes to the finances, but for patients who need to go back to the operating room, you have to consider their deductibles and how you’re going to replace the lens. You want to have a plan in place before your first challenging case. If you’re putting any sort of IOL in, you should know how to take one out. IOL exchanges can be very helpful for some of these refractive surprises.”

If the toric is off alignment, Dr. Loden takes the patient back to the OR for free. “We own our own surgery center facilities, so we take the patient back and re-rotate it,” he says. “That’s part of our process, though it’s very rare because our laser platform [Lensar] integrates with our topography system. It uses real-time iris recognition to mark the axis of astigmatism on the posterior capsule, so we can immediately see on postop day one if the lens is aligned on the capsular tags that are pre-marked by the laser. We can also see if the lens rotated over the last week, though lens rotation is rare nowadays.”

Dr. Loden says that about 15 years ago, when his practice first entered the premium IOL business, they charged separately for the multifocal or accommodating lens and the LASIK or PRK enhancement procedure. “However, we found customers were really unhappy with that model,” he says. “A few actually accused us of deliberately missing the IOL power so that we could charge them for a LASIK touch-up. Now we use a package deal where everything’s included, from YAG laser to LASIK, PRK and dry-eye treatments.

“We’ve been doing that for many years now and it’s been the best process for us, not trying to break it down,” he continues. “If the patient has any questions about why our price is a little higher, we explain that it’s an all-inclusive price. We’re not going to come back and ask for anything more. What’s included will get the patient across the finish line and happy with the outcome.” He adds, “We’ve been quite successful with the Light Adjustable Lens for some of these complex eyes that didn’t do well with multifocals but wanted to be dialed in to 20/20 vision.”

Dr. Miller’s practice offers a service called postoperative refractive enhancements. “It’s like an insurance plan,” he explains. “The patient has the option to pay $500 for this, and if they need PRK or LASIK afterwards, it’s already covered. Our costs for LASIK or PRK are much higher than $500, but they get it for $500. If they don’t need it, then they’ve lost the money, like with typical insurance.”

What’s Holding Premium Lenses Back? Kevin Miller, MD, a professor of clinical ophthalmology and the Kolokotrones Chair in Ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, says, “The industry complains that we aren’t growing the premium market, that it’s been stuck at a pretty low level for a long time. There are a couple reasons for that. “One is that physicians who haven’t trained in the refractive arena or haven’t done oculoplastics just aren’t comfortable having the money talk and charging patients for services,” he says. “That’s always been covered by insurance, so it’s difficult for a lot of physicians and many just avoid the whole thing by not offering premium services to patients. “The second thing holding doctors back is that after their first few premium lens cases they also get their first unhappy multifocal or EDOF patient,” he continues. “These patients consume so much of the surgeon’s time, and the surgeon may say, ‘Forget it. It’s not worth it. I’m just going to stop’ because they haven’t thought through all of the scenarios for when these patients come along. “These patients are in your regular practice too, but when you throw cash into the mix, patient expectations become much higher,” he explains. “You take the patient and turn them into a consumer. It’s a completely different mentality. Patients have problems that you fix. Consumers are looking for a good financial deal. They want whatever it is to be perfect, or they want their money back or they want to trade it in. It’s a new attitude that you have to grapple with as a physician who isn’t used to dealing with patients as customers.” |

Pearls for Success

Cataract surgeons offer these tips:

• Wait for preoperative unhappiness. “If you operate on a patient with a bad cataract, they’ll be more likely to be happy with what you do for them,” Dr. Safran says. “Many doctors are operating on people earlier, before they have significant cataract changes. Many are doing more refractive lensectomy. It’s much easier to make a patient unhappy if they weren’t unhappy to start with. I try to put off cataract surgery until I think the patient is hungry enough where the food will taste good. Waiting until they’re unhappy is a good way to make them happy.

• Implant based on the probability of success. “I work in a mostly referral practice at the university where I see all the problems that occur in the community,” Dr. Miller says. “I think it’s really important not to push multifocals and EDOF lenses onto people who aren’t good candidates for them. I’ve seen patients who have had radial keratotomy or PRK or LASIK getting multifocals. Sometimes they get lucky, and it works out, but I see ones where it doesn’t work out. Then you have to ask, why did the surgeon do that?

“You want to implant based on the probability of success,” he continues. “When you have a patient with prior refractive surgery, the odds of getting the lens power perfect aren’t the greatest, so you’re setting yourself up for disappointment.

“One of my pet peeves is that I see financial incentives biasing doctors’ judgment,” he adds. “Sometimes they get away with it and sometimes they don’t. About half of my patients—and as a mostly referral practice I’m a little bit skewed toward patients with a lot of pathology—aren’t eligible for multifocals or EDOFs, and another 80 percent of them don’t need toric lenses. So, maybe a third of my patients overall are going to get a premium lens and the other two-thirds aren’t. And that’s okay.”

• Handle the lens carefully. “It’s important to never touch the optic,” Dr. Miller says. “Leave the lens in the loading bay of the injector until it’s ready for implantation.”

• Don’t mix and match multifocals. “Multifocals work best when there’s binocular summation at distance and near,” Dr. Miller says. “If the two lenses have different near focal points, this won’t occur optimally. Patients will always prefer one eye over the other and blame the IOL in the poorer-seeing eye for any under-performance.”

• Listen carefully and attentively to the patient. The doctor’s body language sends an important message to the patient that can easily cancel out any spoken words. “You can’t be looking at a computer or looking at studies,” says Dr. Safran. “You have to actually look and listen to the patient. What are they complaining about? You want to get a feel for them, for what’s bothering them, what the nature of their complaint is. Try to determine if it’s a reasonable complaint or an economic issue. Or maybe they didn’t really need surgery. Put everything together and then come up with a strategy to make them happy.”

• Use trial frames to demonstrate potential visual outcomes. “It’s really hard for patients to understand what their vision could look like after enhancements in a phoropter setting, so I put their glasses prescription in a trial frame, put them in and let them walk around the office. I say, ‘This is going to simulate what you’ll be able to see after we do an enhancement procedure.’ I tell them to look at magazines, walk down the hall, walk out the door, walk around outside to simulate real life. If this looks good, then I tell them we can probably solve their complaint with LASIK or PRK. If it doesn’t solve their problem or other issues, then it gets a little more complicated.

• Don’t overlook the contribution of the vitreous. “The vitreous itself is often cloudy and degenerative, and that disrupts the wavefront of a multifocal or diffractive lens much more,” Dr. Safran says. “Very often, a vitrectomy will help these patients, and you don’t necessarily have to do a lens exchange.”

He adds that listening carefully to how the patient describes their vision can clue you in to vitreous problems. “Are they describing something that’s constant or does it vary?” he asks. “They may say things like, ‘It’s cloudy but not always cloudy’ or ‘If I look to the left or right, it’s not as cloudy’ or ‘It’s like a cloud that passes in front of me.’ ”

“Sometimes the patient complains about their vision but doesn’t see a lot of floaters,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “Not every case will require vitrectomy. I often counsel patients about these worsening vitreous floaters and let them know that if the floaters are still causing problems in six months to a year, I’ll refer them to a retina specialist.”

• Sometimes a refund is the best option. “When you reach an impasse where you aren’t going to find a resolution, sometimes the cheapest thing is refunding the patient,” Dr. Loden says. “Sitting and having 20 postop visits with one patient in a calendar year isn’t an efficient use of your time. Sometimes it’s just better to move on, refund the patient, put a monofocal lens in and say, ‘We tried.’”

• Let the patient know that they don’t need to feel rushed into decisions. “Sometimes when you meet a patient for the first time, they’re already scheduled for surgery,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “If you’re finding that the preop is taking a lot more discussion than you anticipate, it may be time to say, ‘Let’s hold off on surgery so you can do some reading and think it over more.’ One of the challenges I see with unhappy multifocal patients is that they didn’t feel like they had time preoperatively to understand the lens options, so afterwards they’re very surprised by some of the side effects they’re experiencing from the lens.”

When it comes to lens exchange referrals, Dr. Safran says feeling rushed is another source of patient unhappiness. “Many patients are under the impression that the lens has to come out within a month or three months or six months, and they feel rushed,” he says. “They feel this urgency. I tell them that there’s no rush—we can take the lens out after a year or two years or even five years. I let them know that I’ll get the lens out and that they can take time to think about it. They can even try glasses first. That often helps a lot, just letting them know that.

“Other times unhappy patients come to me, and their second eye is already scheduled, and they weren’t happy with the first eye,” he continues. “I say, ‘Let’s get the first eye where you can live with it before you get the second eye done.’ A lot of doctors want to get that second eye done right away, when the eyes will work better together, but I think this makes many patients nervous.”

Ultimately, whether it’s refractive error or pathology that’s causing patient unhappiness, surgeons say the patient needs to feel like they’re part of the team. “Patients need to know that you’re looking for an approach that will help improve their vision,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “They want their complaints heard, and they want to know that you’re not going to abandon them or give up on them.”

Dr. Miller is a consultant for Alcon, Johnson & Johnson Vision, BVI, Oculus, Longbridge Medical and LensAR. Dr. Khandelwal is a consultant for Alcon, Bausch + Lomb, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dompé, Kala Pharmaceuticals and Ocular Therapeutix. Dr. Loden is a clinical investigator for Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Safran has no related financial disclosures.