|

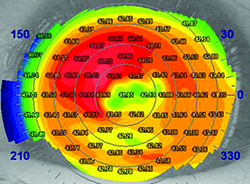

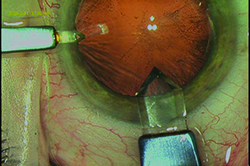

| Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy is more common than many surgeons realize; left untreated, it can degrade a patient’s cataract surgery outcome. (Image courtesy William B. Trattler, MD.) |

Performing the Exam

These strategies will get the preoperative process off to a good start:

1. Remember that just because a cataract is present doesn’t mean it has to be removed. “The prime directive that we all agreed to when we became physicians is: first, do no harm,” says Robert M. Kershner, MD, MS, FACS, professor and chairman of the Department of Ophthalmic Medical Technology at Palm Beach State College, and president and CEO of Eye Laser Consulting, in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla. “Every medical and pharmacological decision we make has the potential to cause harm. Not every cataract needs to be removed. Listen to your patients and hear their complaints, but if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

2. Look for ocular surface disease and treat it before finalizing your measurements. “In my practice I bring about 60 percent of my patients back for a second visit for repeat measurements, because the first measurements may not be as accurate as I’d like,” says William B. Trattler, MD, who practices at the Center for Excellence in Eye Care in Miami, and is a volunteer faculty member at the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University. “The reason is simple: Patients often have ocular surface disease. For example, as demonstrated in the Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients Ocular Surface Study,1 about 80 percent of patients evaluated for cataract surgery have preexisting dry eye; signs include a rapid tear breakup time and ocular surface staining.

“To ensure that this doesn’t impact our outcomes, when patients come in for a consultation for cataract surgery we carefully evaluate them for ocular surface disease at the slit lamp,” he continues. “We also perform topography and IOLMaster. I have found that performing a preoperative topography on all patients scheduled for cataract surgery provides helpful information, whether or not the patient is going to receive a premium IOL. Topography will often pick up dry eye, as well as subtle epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, either of which will impact the visual outcome. Topography can also reveal mild keratoconus that has been undiagnosed.

“If the readings appear irregular and the eyes are dry, I’ll place the patient on a topical steroid like Lotemax gel or Pred Forte for two or three weeks,” he says. “Then I’ll bring the patient back for repeat measurements. This has made a big difference in terms of getting more accurate keratometry, which significantly impacts our cataract surgery outcomes.

“Once you start identifying and treating dry-eye patients aggressively prior to cataract surgery,” he adds, “you’ll end up doing it more and more, because you’ll realize how many patients really have dry eyes, and how treating their condition and repeating measurements can result in improved intraocular lens calculations.”

3. Consider treating any epithelial basement membrane dystrophy before performing the surgery. “A lot of patients—more than you may realize—have epithelial basement membrane dystrophy that can significantly impact their visual outcome,” says Dr. Trattler. “Just today, for example, I saw a patient who had had surgery with another doctor; he came to me because he wasn’t happy with his visual result. The implant looked beautiful, everything was fine, the macula was normal, but the patient had EBMD and some dry eye. That was the source of the reduced vision quality in the eye that had been operated on. The patient did not recall being told about EBMD prior to his surgery.

“EBMD can impact the measured shape of the cornea, and it can therefore impact the postoperative results,” he continues. “So, identifying the condition and talking with the patient about whether to treat it beforehand is critical. If a patient has irregularity, enough that you feel it requires treatment, you can perform an epithelial debridement to smooth the corneal surface. Some doctors will use an excimer laser and perform phototherapeutic keratectomy for patients with EBMD. A small percentage of patients who are at risk for delayed epithelial healing may also be treated with an amniotic graft to help the epithelium heal rapidly after debridement.

“Following epithelial debridement or PTK,” he adds, “one should advise the patient that she’ll need to wait about two months to re-take the keratometry measurements, to ensure that they’re relatively accurate.”

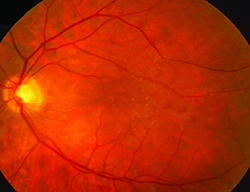

4. Perform a careful preoperative retinal exam and take steps to minimize the risk of cystoid macular edema. “Although CME with retinal detachment is a much-less-frequent complication of cataract surgery today, it still occurs, and is often the cause of a poor outcome and the basis for a lawsuit,” says Dr. Kershner. “The best way to prevent this is a thorough preoperative retinal examination. I’ve seen too many referred cases where pre-existing lattice degeneration, maculopathy, vitreoretinal degeneration or a retinal tear or hole was missed. Worse, I’ve seen cases where these were recognized and charted but not addressed prior to surgery.

“Don’t become a legal statistic,” he continues. “You can never be faulted for being safe and thorough, but you’ll have to answer for a poor surgical outcome caused by something that could have been eliminated as a complicating factor—if only it had been addressed before surgery. Consider what any prudent ophthalmic surgeon would do under similar circumstances, and if you don’t think you’re doing that—whatever is truly in the best interest of the patient—then get outside help. If you fail to meet the standard of care, you’ll be answering to a lawyer.”

“Patients who are at increased risk of developing CME,” adds Dr. Trattler, “include patients with various retinal conditions such as epiretinal membranes, a history of retinal vascular occlusions, diabetic retinopathy or uveitis. The key to managing the risk of CME is prevention. Using topical nonsteroidals for three days prior to cataract surgery appears to reduce the risk of developing CME, and combining therapy with a topical corticosteroid can also help. These anti-inflammatory medications are often used for four weeks postoperatively, and in some cases are prescribed for an additional month or two.”

Choosing the IOL

Selecting the optimum type and power of IOL is essential to a great outcome:

5. If multiple technologies are used to measure astigmatism, make sure they agree. “If one device suggests there is 1 D of astigmatism at 85 degrees and a second device says there is 1.8 D of astigmatism at 95 degrees, consider initiating a treatment for ocular surface disease,” suggests Dr. Trattler. “Then bring the patient back for repeat measurements.”

6. Use aspheric lenses. “Aspheric lenses correct the spherical aberration in the cornea,” notes Jack T. Holladay, MD, FACS, clinical professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of medicine in Houston. “That translates to improved vision. Studies have shown that aspherical IOLs improve vision by about one line and improve contrast sensitivity by about 30 percent.2-5 Most doctors have embraced this idea, but many of them don’t realize that there’s a second benefit to reducing residual spherical aberration: Residual spherical aberration not only reduces your quality of vision, it also causes your refraction to change as a function of pupil size. With positive spherical aberration, your vision will tend to shift toward nearsightedness when your pupils are larger in darker conditions. So, aspheric IOLs not only provide you with better-quality vision, they also give you a more constant refraction at various light levels.

|

|

| A thorough retinal exam before surgery can catch problems that may lead to cystoid macular edema—and potential lawsuits—later. (Image courtesy Robert M. Kershner, MD.) |

7. Use equi-convex lenses. “This refers to a lens design in which both surfaces have the same curvature,” explains Dr. Holladay. “This design does a better job of maintaining image quality in the face of lens tilt and decentration, and the principal planes don’t shift as a function of power. Most of the popular lenses in use today incorporate this design. If you’re using one that does not incorporate this design, you should consider switching to another lens.”

8. Reconsider your habitual choice of IOL. “Just because you’ve implanted a particular IOL thousands of times with excellent results does not mean that it’s the best choice for a particular patient,” says Dr. Kershner. “Also, it’s important to revisit your routine IOL choices frequently—at least twice a year. Technology changes. Your IOL rep may be a longtime friend, but there might be better options out there that you have not considered. In fact, the best choice may not be necessarily be the latest and greatest; sometimes IOLs that have been available for decades will be the best choice for your patient.”

9. Don’t use a two-variable formula when calculating lens power. “If you’re using a two-variable formula to predict the lens position, you’re behind the times,” says Dr. Holladay. “The formulas that use two variables are mostly older ones. The Haigis formula, for example, uses axial length and anterior chamber depth, while SRK/T, Hoffer Q and Holladay I use axial length and Ks. With a two-variable formula you’ll get about 60 percent of your cases within 0.5 D. That’s not very good, and it puts your outcomes in the bottom 50 percentile.

“Today there are three formulas that use up to seven variables: The Holladay II, the Olsen II and the Universal II formula from Graham Barrett,” he continues. “Those formulas use axial length, K-reading, horizontal white-to-white distance, anterior chamber depth, lens thickness, refraction and age of the patient. Using any of these formulas will result in 70 to 75 percent of your cases being within 0.5 D of your target. ASCRS did a study that showed that between 60 and 70 percent of doctors are now using a seven-variable predictor formula, because they have access to the Holladay II formula in the IOLMaster, the LenStar and the Verion system.

“If you’re not using one of these advanced formulas, you need to catch up,” he says. “It’s not hard to do because the Holladay II is available on all of these instruments.”

10. Personalize your lens constant. “Probably 30 percent of surgeons still don’t personalize their lens constant,” notes Dr. Holladay. “Manufacturers’ constants are based on averages and numerous assumptions that may not apply to any given surgeon. Also, your surgical technique and choice of IOL will affect the value of your ideal constant. The only way to pin down the constant that will give you the best outcomes is to measure your patients’ postoperative refractions and check that against the constant you’re currently using. [For more about how to personalize your constants, see “Another Step Closer: Lens Constant Customization” in the January 2010 issue of Review.]

“If you use one of the advanced multi-variable formulas and also personalize your lens constant, you can get up to 82 percent of cases within 0.5 D of your intended target,” Dr. Holladay continues. “That’s what you should be doing, because with today’s premium lenses, if you’re not within 0.5 D 80 percent of the time, more than 20 percent of your patients will be unhappy.”

Dr. Kershner agrees. “It’s important to make sure the formula you use is backed up by solid data demonstrating reproducible results from your own outcomes analysis,” he says. “Many a surgeon has quoted the thought leaders or literature results, but not as many can quote their own statistics. Just because Dr. X can achieve 20/10 results with his lens constant and his own tweaked formula, does not mean that you will get the same results as he does. You need to carefully track and monitor your own outcomes and adjust your formula accordingly.

“Furthermore, even if your formula is correct, it won’t ensure reproducible results unless the same people in your practice are taking the same measurements every day and inputting the data the same way,” he adds. “In other words, you need to avoid the inadvertent introduction of other variables into your measurements simply because on Tuesdays, Tom takes the measurements and Sally makes the calculations, and on Thursdays the new person does it all. To maintain the integrity of your data, you need to control as many factors that could introduce errors as possible.”

11. When calculating the astigmatism correction, use an advanced calculator that takes IOL power and effective lens position into account. “One of the pitfalls of using some online calculators is that they are only accurate for a 22-D lens,” notes Dr. Holladay. “They assume the ratio of the lens toricity that you’ll need to correct the corneal astigmatism is 1.5 to 1, but that’s only true for a 22-D lens. For example, a 3-D toric lens will correct 2 D of astigmatism at the cornea when the lens is 22 D. But if you have a 10-D lens, you need almost 3.5 D of toricity in the lens to correct 2 D of corneal astigmatism. And if you have a 30-D IOL, you’ll only need about 2.25 D of toricity to correct 2 D of corneal astigmatism.”

Dr. Holladay explains that the less-precise calculators produce good results in the majority of eyes because about 70 percent of the lenses in use today are within 3 D of 22 D. “About twice as many 22-D lenses are used as any other curvature because refractive errors are clustered around emmetropia,” he says. “So the unusual eyes—30 to 40 percent of eyes—are not as common. They don’t push the curve enough to make it look wrong. However, some calculators now do take the curvature of the lens into account. The AMO Express calculator takes this into account; the Verion System from Alcon corrects for this, and they’re upgrading their online calculator to do the same. The Holladay IOL Consultant also takes this into account. In fact, I wrote the software for all three. Bausch + Lomb should also have this in their calculator upgrade sometime this year.

“For now, doctors need to be aware that not every calculator compensates for this,” he concludes. “Using an older calculator will result in undercorrecting the astigmatism when using low-power lenses and overcorrecting astigmatism when using high-power lenses. That’s why you’re more likely to end up with more than a half diopter of residual astigmatism as the lens curvature gets farther from 22 diopters.”

12. Be aware that the lens may shift differently following manual capsulorhexis than following femtosecond capsulotomy. “If you perform manual capsulorhexis there appears to be a slight forward shift of the lens between the first week and month six,” says Dr. Holladay. “If you perform a femtosecond laser capsulotomy there may be a slight posterior shift in the IOL in the same time frame. The reason for this shift in opposite directions—and exactly how great the shift is likely to be—is still under investigation. But this may impact your outcomes, depending on which technology you’re using, so personalize your lens constant.”

Planning Your Approach

To avoid losing the advantages gained with the previous steps:

13. Make sure you don’t induce a refractive change with your planned incision. “There is simply no such thing as ‘One incision size and location fits all,’ ” says Dr. Kershner. “As the great Spencer Thornton, MD, has taught us, all incisions in the cornea will act as if tissue has been added. That means there is no such thing as a ‘refractive-neutral’ incision. And remember that where you cut—not how you cut—will determine the incision’s effect on the overall power of the cornea. So, monitor your incision placement, whether the incision is made with a diamond keratome or a femtosecond laser. You want to leave the patient with less than 0.5 D of astigmatism and less than 0.25 D of spherical error; that means not inducing a refractive change with your incision. If you don’t know how to minimize the refractive impact of your incision, take a course and read a text on the surgical correction of refractive error.”

14. Make sure all of your patients end up with less than 0.5 D of residual astigmatism. “Any more than half a diopter of astigmatism will result in diminished quality of vision at distance,” says Dr. Holladay. “To accomplish this you need to know how much astigmatism your surgical technique will induce, and you need to use toric lenses to maximum advantage. Toric lenses come in step sizes that are 0.75 D, which converts to about 0.5 D at the corneal plane. So if used properly, the farthest you can be from the perfect astigmatic correction is about 0.25 D.

|

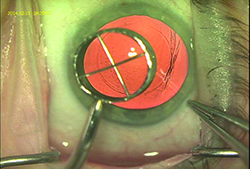

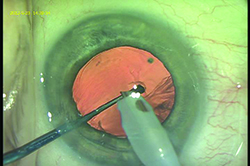

| Using a device to make a capsulotomy diameter mark on the cornea can provide the surgeon with a visual guide that will help create a capsulotomy very close to the intended size. (Image courtesy R. Bruce Wallace III, MD.) |

15. Take posterior capsular astigmatism into account. “As Doug Koch, MD, first pointed out, the posterior surface of the cornea in most people contributes about 0.5 D of against-the-rule astigmatism to our vision,” says R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, La., and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Louisiana State University and Tulane Schools of Medicine in New Orleans. “That’s enough to have an impact on your outcomes. Generally speaking, if you’re making a 2.5- to 3.0-mm temporal corneal incision, then posterior corneal astigmatism won’t have a big impact on your outcome; your incision will produce a compensating effect. On the other hand, if you’re making a superior incision you have to take this into consideration because your incision will add to the against-the-rule astigmatism. So if you’re making a superior incision, adjust your astigmatism correction accordingly.”

Performing the Surgery

Once you’re in the OR:

16. Before surgery, verify that the patient data is correct—multiple times. “Make sure your system protocol and pre-flight checklist incorporate a series of checks and balances to verify that the patient’s data is correct; that the data you are using is the data belonging to the patient you are about to operate on; and that no fewer than three different individuals have verified this,” says Dr. Kershner. “I’ve often appeared as an expert witness to help defend a physician because of a poor outcome, when the office had the best intentions and the doctor had the right skills but the data used was from the wrong patient. Take nothing for granted. Verify, verify, verify.”

17. Make sure your anterior capsulorhexis is the size you intend. “Getting the size of your anterior capsulorhexis right helps with IOL centration and stability,” says Dr. Wallace. “I find two strategies useful. First, when I want to make a 5- to 5.5-mm diameter anterior capsulotomy, I create what’s called a capsulotomy diameter mark—an indention on the corneal surface marking the edge of a 6-mm optical zone. Using that as a visual guide, I stay just inside that mark when I’m creating the 5- to 5.5-mm anterior capsulotomy. It’s easier to size the capsulotomy accurately with that as a reference point.

“A second strategy that helps is fixating the globe during the capsulotomy using a cyclodialysis spatula through the sideport incision,” he says. “This stabilizes the globe so that when you’re making the capsulotomy with forceps the process is easier to control, resulting in the most accurately-sized and most complete anterior capsulotomy.”

18. If possible, use intraoperative aberrometry. “When Alcon bought WaveTec,” notes Dr. Holladay, “it was on condition that WaveTec would do a controlled study demonstrating that their intraoperative aberrometry technology—the ORA—could statistically improve outcomes, even when a surgeon was using the latest formulas and personalizing his constants. And they did. About 20 surgeons went from having 82 percent of their outcomes within 0.5 D, using the Holladay II formula and a personalized constant, to 92 percent within 0.5 D by also using the ORA.

“Today, many surgeons are buying the VerifEye for that exact reason: It reduces the number of patients you have to bring back for a lens exchange or laser surgery, which costs a lot more than the per-case cost of using the VerifEye,” he continues. “The reality is, this is the level of performance that doctors are being measured against today. If you use the seven-variable predictors, personalize your lens constant and do intraoperative measurements you can get upwards of 90 percent of your patients within 0.5 D of the intended target.

“Of course, purchasing the equipment to perform intraoperative aberrometry costs money, and surgeons early in their practice may not have that option,” he adds. “But you can get close to that by using the more advanced formulas and personalizing your constant. That’s the standard of care today.”

|

| Making a sutureless incision that’s as square as possible, rather than logitudinal, can help prevent leakage. To create a square incision, stay in stroma as long as possible when creating the incision. Using a diamond knife makes this easier to do. (Image courtesy R. Bruce Wallace III, MD.) |

Managing Complications

Obviously, the best planning and surgical execution may not lead to the best outcome if a complication occurs.

20. Take steps to prevent incision leakage. Dr. Wallace notes that a leaking incision can lead to a host of other complications (including endophthalmitis), so it’s crucial to ensure that your incisions are watertight. “I’ve found that the best way to prevent leakage with sutureless incisions is to make an incision that’s as square as possible,” he says. “When creating the incision, try to stay in stroma as long as possible. This usually creates what appears to be a square incision rather than a longitudinal incision. I also recommend using a 2.8-mm diamond knife, because I’ve found that you can direct a diamond knife more easily; it will stay in stroma longer. That allows for stronger incision closure after stromal hydration.”

21. Stop and reevaluate if the capsule ruptures. “One of the most important things to do when you unintentionally rupture the capsule is to immediately stop the procedure,” says Dr. Kershner. “Do not proceed until you have reassessed the situation and determined how to move forward in a safe way that will ensure a successful outcome. Make sure that you’ll maintain the integrity of the remaining capsule while you remove vitreous and remaining lens material; then complete the procedure, and be sure to implant the IOL in a way that ensures it will remain stable. If you have any uncertainty about any of this, seek help immediately.”

Dr. Wallace notes that a surgeon can take precautions to avoid posterior capsule tears. “I designed an instrument called the Wallace Guardian, made by Storz, in which I have no financial interest,” he says. “It’s a blunt chopper that can be used to manipulate the nucleus, but also is helpful for protecting the posterior capsule from the phaco energy. I place it posterior to the phaco tip when I’m almost done removing the nucleus; it acts as a barrier, making it very hard to engage the posterior capsule with the phaco tip.”

22. Reposition the IOL if it ends up misplaced. “A misplaced IOL is one that is not centrally placed, is tilted or is more posterior or anterior than you expected,” explains Dr. Kershner. “This problem is much more common than many would think. Surgeons often miss this diagnosis because they don’t assess the actual intraocular location of the IOL after placement.” (He notes that a misplaced IOL is not the same as a dislocated IOL, which is the result of preexisting or intraoperative trauma.)

|

| A tool such as the Wallace Guardian (Storz), designed to be a blunt chopper, can help protect the posterior capsule by keeping the phaco tip from contacting the capsule during phacoemulsification. The tool can be placed behind the phaco tip near the end of nucleus removal. (Image courtesy R. Bruce Wallace III, MD.) |

23. Look out for elevated intraocular pressure following surgery. “There are a variety of reasons IOP may go up following cataract surgery,” notes Dr. Trattler. “A pressure rise can be caused by inflammation, lens particles that are liberated during the surgery or retained viscoelastic. The key to preventing a serious problem is prompt diagnosis. One option is to see patients the same day instead of waiting for them to come back the next day. I have many of my patients, especially those that live more than an hour away from our office, return the same day—anywhere from one or two hours postop to four or six hours. Fortunately, my surgery center and office are in the same building.

“If elevated eye pressure is a major issue,” he adds, “additional steps can include providing pressure-lowering eye drops at the conclusion of cataract surgery. Also, certain viscoelastics can raise the pressure more than others, so switching to a viscoelastic that is less likely to raise IOP is an option to consider.”

24. Be aware of the possibility of cystoid macular edema. As noted earlier, the best treatment for CME is prevention, starting with a careful preoperative retinal exam to detect retinal problems such as lattice degeneration, maculopathy, vitreoretinal degeneration, an epiretinal membrane or a retinal tear or hole. “The risk also goes up if your patient has vitreous loss during cataract surgery,” notes Dr. Trattler. “If CME occurs despite your precautions, either restart or increase your anti-inflammatory therapy. Referring the patient to a retina specialist for further treatment may also be helpful.”

25. If something does go wrong, admit it and be straightforward about it. “If you want to end up with a happy patient, you have to recognize when things don’t go according to plan and immediately address it,” notes Dr. Kershner. “If you can’t figure out what happened, seek out someone else who can. A patient will not fault you if you make every effort to help him; but if you fail to recognize a problem, ignore the patient’s complaints or fail to seek out the help the patient needs, it will come back to haunt you. No doctor is perfect and neither is any procedure. If you make that clear to the patient before surgery, you won’t have any backpedaling to do.” REVIEW

1. E-Poster 891: Trattler W, Goldberg D, Reilly C, et al. Incidence of Concomitant Cataract and Dry Eye; Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients. World Cornea Congress; Boston, Mass.; April 8th, 2010.

2. Holladay JT, Piers PA, Koranyi G, van der Mooren M, Norrby NE. A New Intraocular Lens Design to Reduce Spherical Aberration of Pseudophakic Eyes. J of Refract Surg 2002;18:683-691.

3. Kurz S, Krummenauer F, Thieme H, Dick HB. Contrast sensitivity after implantation of a spherical versus an aspherical intraocular lens in biaxial microincision cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007; 33:393–400.

4. Packer M, Fine IH, Hoffman RS, Piers PA. Initial clinical experience with an anterior surface modified prolate intraocular lens. J Refract Surg 2002;18:692–696.

5. Mester U, Dillinger P, Anterist N. Impact of a modified optic design on visual function: Clinical comparative study. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003; 29:652– 660