Surgeons differ as to whether zero astigmatism is a feasible—or even uniformly desirable—goal of cataract surgery. Here, experienced surgeons discuss whether, when and how to pursue zero astigmatism in the setting of cataract surgery.

Arun Gulani, MD, founding director and chief surgeon of the Gulani Vision Institute in Jacksonville, Florida, thinks that although astigmatism can be useful in select cases, surgeons should strive to eradicate it most of the time.“The attitude of the surgeon should be intolerant to astigmatism at any level. There’s no such thing as a tolerable factor over zero,” he states. “Not reaching that zero point is human, and could be an honest mistake or just arise from natural variations in healing between patients. But to not aim for it is unacceptable in this day and age.”

Dr. Gulani, who teaches about astigmatism elimination in cataract surgery in the United States and abroad, adds that a substantial part of his practice involves correction of complications and providing second opinions for patients who’ve already undergone laser vision correction or premium cataract surgeries. “Astigmatism has been the most common residual refractive error that I’ve seen that could have been corrected by the surgeon,” he says. “In recent studies, it’s been documented to be the biggest reason for dissatisfaction following successful premium cataract surgery. It’s also an element that can easily be corrected, but results in unhappy patients and disturbs patient/doctor relationships.”

“Can we approach zero? Sure, but we can’t guarantee zero,” opines Natalie A. Afshari, MD, FACS, professor of ophthalmology and chief of the division of cornea and refractive surgery at the Shiley Eye Institute, University of California, San Diego, who thinks that promising

|

|

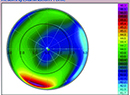

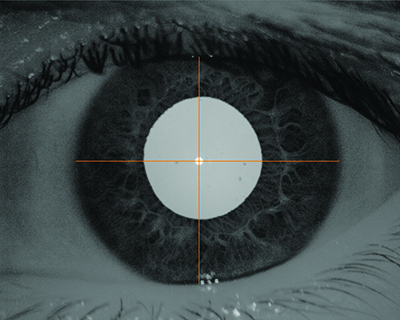

| Corneal topography (top) shows approximately 1.6 D of astigmatism. Scheimpflug imaging (bottom) shows that the simK (blue circle) agrees with the topography, but that the total corneal refractive power (red circle) measures 2.2 D of astigmatism, having accounted for the posterior corneal surface. Considering only the anterior corneal surface’s contribution to astigmatism would have resulted in at least 0.6 D of astigmatism left uncorrected. (Image courtesy Jeremy Kieval, MD.) |

Like Dr. Afshari, Jeremy Kieval, MD, a partner and director of cornea, cataract and refractive surgery at Lexington Eye Associates in Massachusetts, who also serves as an instructor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, says that minimizing astigmatism as much as possible is important; but he also thinks we’re too far from understanding all the potential contributing factors to completely eliminate it every time. “I think there are many factors, like dry-eye disease and age-related changes in the cornea, as well as postoperative changes and capsule contraction. Additionally, the implanted lens creates some element of tilt. All of those things will contribute just minimally—a quarter- or a half-diopter—to astigmatism. I think that to really get down to zero, there will need to be a lot more understanding in terms of corneal biomechanics, dry-eye disease treatments, basement membrane dystrophy management

Is Astigmatism Always Bad?

Dr. Kieval adds, however, that the drive towards zero

“For example, you might have a patient with essentially zero

Dr. Kieval looks at the spectacle wear of patients with zero spherical equivalent and

Daniel H. Chang, MD, of Empire Eye & Laser Center in Bakersfield, California, isn’t convinced that patients benefit from any amount of astigmatism. “Although it’s commonly suggested that uncorrected astigmatism can help with near vision, I do not use this as a viable clinical strategy for improving

Dr. Kieval always strives for zero

Preop Workup

Just as a thorough preoperative workup is necessary to choose an IOL with the proper spherical power, it’s also critical in order to treat astigmatism successfully. Many surgeons turn to corneal topography. “First we do refraction. Then we also do a corneal topography with Scheimpflug imaging using the Pentacam (Oculus),” explains Dr. Afshari. “That lets us see how much corneal astigmatism is there: Is it the regular bow-tie pattern, or is it irregular? The third step we do is an astigmatism check. We do an axial-length measurement and get the keratometry values during the preoperative visit.”

Scheimpflug imaging is also crucial to Dr. Kieval’s astigmatism treatment planning. “I rely heavily on Scheimpflug imaging for both magnitude and axis of astigmatism. I use the Pentacam, and I like the true net corneal power feature because it looks at the whole cornea by incorporating the posterior aspect

Dr. Gulani thinks that surgeons should use all of the modalities at their disposal to assess astigmatism as part of a comprehensive workup. “Before surgery, it’s important to measure

Dr. Chang uses his topographer to help assess the quality of his keratometry. “I use the IOLMaster 700 (Zeiss) to provide the mean K’s, as well as astigmatic power and axis. I then use the Atlas topographer (Zeiss) to verify visually that what I’m getting on the IOLMaster 700 makes sense. The topography also gives me an overall map of the cornea, which is important because biometers will not show when there is irregular astigmatism. In essence, the topographer verifies whether the Ks from my biometer are any good,” he says.

“I’ll do at least two different measurements with the same device if I’m going to correct astigmatism—ideally on separate days,” Dr. Chang continues. “I do this to look for fluctuations of the ocular surface, so I like to measure it on two separate days with the same device. If I have two devices and two different readings, I don’t know if the K changed, or if it’s just the different devices giving me different readings. After obtaining multiple measurements, I look at all of the readings to determine the power and axis that I plan to treat— for example, ‘1.25 D at 180 degrees’— which lets me determine my desired surgical approach.”

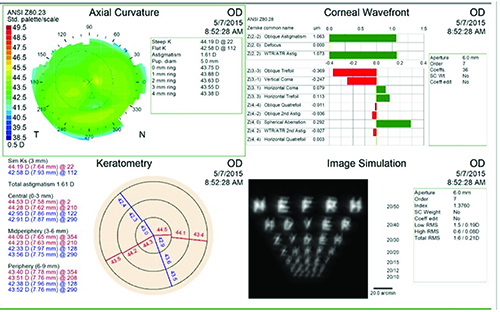

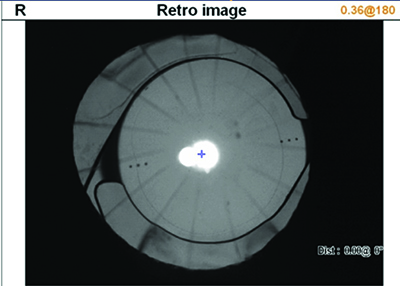

Dr. Chang has devised a unique way to take his preop data into the OR once he’s verified it. “After using my topography to guide my axis selection, I will use the pupil image taken by the topographer. I visualize the iris structures to translate my figures onto the eye at the time of surgery. It’s a way to directly correlate my preoperative measurements with what I do intraoperatively. The IOLMaster 700 now prints an iris image as well, but my current workflow still involves the images from my topographer. I export it as a JPEG,” he explains. “Then I mark a crosshair vertically and horizontally over the corneal vertex, or the light reflex, which George Waring and I have described as the subject-fixated coaxial corneal light reflex. It’s basically the fixation light that’s reflected off the cornea. I place a line vertically and horizontally, and I take the image and digitally enhance it with Photoshop to maximize the contrast of the iris structures. At the surgery center, I put the patient in the slit lamp at the YAG laser. Using the preoperatively marked and enhanced pupil image, I then put a laser spot at 0° and 180° to reference the cardinal meridians. When I get the patient on the table, I then take a compass and mark the steep axis of astigmatism,” he says.

Douglas D. Koch, MD, professor and the Allen, Mosbacher, and Law chair in ophthalmology at The Cullen Eye Institute, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, combines topography and readings from two different biometers. “My standard workup is to use the Galilei (Ziemer) for topography, and both the IOLMaster 700 and the Lenstar (Haag-Streit). I’m also currently using the Cassini (Cassini

Overcorrect? Undercorrect?

Some surgeons believe certain patients benefit from a small amount of astigmatism, and that they may be dissatisfied if it’s corrected to zero. A related issue is

|

Daniel H. Chang, MD, creates a JPEG of an image from his topographer, enhancing it in Photoshop to optimize his view of the unique iris structures, and adding crosshairs over the subject-fixated coaxial corneal light reflex. He references this enhanced image when marking the cardinal meridians and the steep axis of astigmatism on the day of surgery. (Image courtesy Daniel Chang, MD.) |

Dr. Kieval bases his decisions about adjusting for anticipated changes in astigmatism on the preop Scheimpflug imaging. “In terms of over- or undercorrecting, I don’t feel like I need to use nomogram-like adjustments because I think that net-power data point on the Scheimpflug imaging is giving me the true power of the cornea. The only thing I will consider with regard to variance is the shift from with-the-rule to against-the-rule astigmatism with time and age. I’ll account for that more in my younger patients, such as the early-onset cataract cases—the 40- and 50-year-olds. But it’s not a dramatic accounting. If it’s a pediatric case, like a teenager with a congenital cataract or posterior polar cataract, I tend to

Dr. Koch says that research suggests that this dynamic component of astigmatism that shifts from with the rule to against the rule appears to be slight and related to age.

Dr. Chang credits Dr. Koch’s research regarding the posterior cornea with informing some of his decisions about treating astigmatism. “Primarily based on the work of Doug Koch at Baylor, we have become aware of the posterior-corneal component of astigmatism,” he notes. “Depending on the axis, we should make a correction for total corneal astigmatism. As a rule of thumb, if the anterior corneal astigmatism is with the rule, I’ll subtract 0.5 D; if it’s against the rule, I’ll add 0.5 D. Then, I’ll use LRIs or a toric lens with the appropriate astigmatic power.”

With regard to the against-the-rule drift over time, however, Dr. Chang prioritizes immediate patient satisfaction over accommodating a gradual shift. “It’s tough to account for a decade of drift,” he says. “I really try to make the patient happy in the early postoperative period. If it drifts by 0.5 D over 10 years, they’ll probably forgive me. I may leave a little with-the-rule astigmatism, but I definitely try to get close to zero on the day of surgery.”

Dr. Gulani says that skilled surgeons may be able to use a patient’s astigmatism to create a customized visual outcome. “In many cases, we can use astigmatism to our advantage by leaving natural astigmatism to help

The Role of LRIs

With the availability of

| “What I really like are intrastromal relaxing incisions, which I can use to correct about a half-diopter. What’s nice about them is that they don’t cause any discomfort or dryness, and they can just give you a little, tiny correction that is sometimes just what you need with a premium IOL.” —Douglas D. Koch, MD |

Dr. Gulani creates incisions using a femtosecond laser intraoperatively to treat astigmatism. “During surgery, the femtosecond laser can create accurate limbal relaxing—or astigmatic keratotomy—incisions, which can be created during, but opened during or after, cataract surgery,” he says. “Of course, the modality of laser vision surgery is always available after premium cataract surgery to address and correct any residual astigmatism, right down to the zero-tolerance level. Not as accurate as laser vision surgery, but surely feasible and cost-effective, is an LRI at the slit lamp itself after cataract surgery for any residual astigmatism.”

Dr. Kieval describes manual LRIs at the slit lamp as his own version of “postop enhancement” for small amounts of astigmatism. “I think that’s different from what many people do,” he says. “I treat that astigmatism with an LRI at the slit lamp even if it’s

Dr. Afshari says she finds herself using LRIs less frequently in recent years. “Now I do far fewer of them because of toric implants,” she says. “That’s one factor; another factor is if the patient’s astigmatism is low enough that I can help it by the placement of my wound superiorly vs. temporally: I’ll adjust my wound based on the steep axis to decrease

Another surgeon who prefers a toric-IOL astigmatism solution is Dr. Chang. “The problem with LRIs is that you’re never too sure of what you’re going to get,” he says. “I have found that while femtosecond-based LRIs provide far more precise cuts than manual incisions, variable corneal biomechanics can still

Dr. Gulani generally avoids manual LRIs for patients seeking premium results. “One cannot implant a premium lens implant and do an inaccurate manual LRI to complement it—though some cases of low-level astigmatism and high predictability, like a normal cornea, could justify this—but in most cases there are multiple astigmatic factors at work that will surprise the surgeon who thinks they were diligent enough,” he says.

The Femto Factor

Astigmatic keratotomy by femtosecond laser gets mixed reviews. “I don’t use femtosecond, but many colleagues like creating AKs with

“I find myself doing a lot less femtosecond laser cataract surgery over the

“The evidence does not clearly support that you get a better overall result or that you have improved safety,” says Dr. Koch of FLACS. “The safety is comparable, but the evidence doesn’t suggest that it’s better. There are a couple of studies that suggest you may be a bit more accurate with

“What I really like are intrastromal relaxing incisions, which I can use to correct about a half-diopter,” Dr. Koch continues. “What’s nice about them is that they don’t cause any discomfort or dryness, and they can just give you a little, tiny correction that is sometimes just what you need with a premium IOL. From that standpoint, I do like laser procedures, but the data are not in to support them, aside from

Wavefront Aberrometry

Dr. Chang says that he doesn’t use the ORA VerifEye (Alcon) for intraoperative aberrometry. Dr. Koch only uses it for a limited number of cases. “I don’t find it particularly helpful in most of my patients,” he says. “The measurements we obtain in our office are so good that I don’t feel the need to use wavefront very often in toric-IOL situations. There are cases in which I’ll use it if my preoperative data are conflicting, and I also use it in post-LASIK eyes to help me with astigmatism correction sometimes, but I’m just not a strong advocate of the ORA, only because the cornea has been so modified by the time you get to that point in the operation that I don’t think it can match the precision and the accuracy of the measurements that you get preoperatively in the clinic.”

Dr. Afshari finds it helpful to compare wavefront aberrometry’s readings with her preoperative data. “We do intraoperative aberrometry with the ORA,” she says. “But beforehand, obviously, we determine how much of the astigmatism is corneal and how much is lenticular. Then, we see if all of the numbers match or are at least

The Toric Threshold

When should you use a toric lens for optimum astigmatism management? It depends on whom you ask. “For

But beyond a threshold amount of astigmatism, “It is a discussion with the patient,” she says of the decision to use a toric IOL. “When I look at patients with around 1 D of astigmatism, many are fine with wearing glasses. They’re used to them, or they like

“I prefer a toric IOL solution for astigmatism,” says Dr. Chang, who estimates that when treating presbyopia he implants about 55 percent toric vs. 45 percent

Dr. Koch’s threshold for toric-IOL use also takes the posterior-corneal effect into account: “It would be around 1.5 diopters for with-the-rule, and about 0.5 against-the-rule,” he says.

“Intraoperatively, I’m geared towards a toric-lens solution for astigmatism,” says Dr. Kieval. “The most typical protocol if the patient has 1 D or more is to treat with a toric lens intraoperatively. If it’s anything less than a diopter, I tend to try to operate on axis, and then treat any residual astigmatism with an LRI postoperatively in the office. If there’s residual astigmatism, I’ll manage it with a limbal relaxing incision afterward. The literature soundly supports the use of toric lenses over the intraoperative limbal relaxing incision. But I also think that I can treat low enough that if there’s 0.75 D preoperatively, I can hope that an on-axis incision will be enough. If it’s not enough because the patient really needs zero

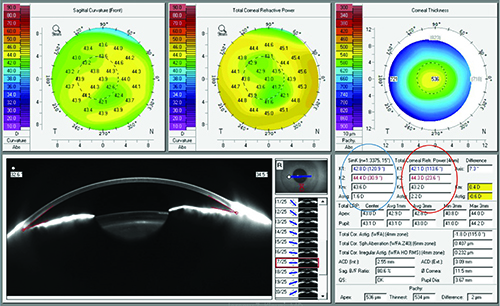

|

| Arun C. Gulani, MD, believes that some surgeons may avoid toric IOLs due to concerns about lens selection, alignment and staying power once placed. He says they can deliver great visual outcomes in skilled hands, however, even in complex eyes like the post-RK one shown here. (Image courtesy Arun Gulani, MD.) |

Dr. Gulani decides to recommend toric lenses on a case-by-case basis. “As I always teach, there should be no mathematical cutoff point, but a clinical judgment about when to use a toric lens or when to use an LRI, either manual or femtosecond-laser-assisted. Given the accuracy and stability of toric lenses, I have a low threshold to use them in patients with astigmatism and associated cataracts, with

“Toric lenses are extremely accurate,” Dr. Gulani continues. “I have used toric lenses not only in virgin eyes with

Dr. Gulani adds that some of the surgeons who call and email him perseverate on having the latest “magic bullet” technology for toric alignment. “Additionally, surgery is an art, and there are nuances like how to not thoroughly clean the underside of the anterior capsule along the axis, or how to ovalize the capsulorhexis in deep-chamber cases like status post-RK or keratoconus, and then also how to align the lens during surgery without additional and laborious steps.” He uses the Gulani toric marker and alignment system (Bausch + Lomb).

“With nearly two decades of using toric lens implants in routine, complex and extreme cases, I have not had to rotate any implants post surgery to date,” says Dr. Gulani.

Dr. Koch notes the recent study showing that the Tecnistoric IOL (Johnson & Johnson Vision) tends to rotate in the eye more than AcrySof

Dr. Chang says that wound characteristics may influence whether or not toric IOLs rotate after cataract surgery. “When you’re using toric lenses, you’ve got to be really meticulous in implanting them,” he says. “Beyond marking the eye, unfolding the lens and aligning it in the eye, my biggest suggestion is to ensure that the wound is well sealed. A stable globe postoperatively provides a stable environment for the IOL, but if the eye becomes

Dr. Chang says that EDOFs are known to have refractive forgiveness for spherical error; but he says you can have that forgiveness for astigmatic error using these lenses, too. “However, you can’t just throw the lens in and expect it to magically take care of astigmatism. If you end up slightly hyperopic, and you left-shift the defocus curve, the extended focal range will provide some refractive forgiveness for distant vision, even for astigmatism,” he explains. “The tradeoff is that when you are slightly hyperopic, you lose a little bit of near vision in exchange. Therefore, it’s still best to correct all of

“I encourage all eye surgeons to develop a zero tolerance for astigmatism,” says Dr. Gulani. Embracing as many pearls as possible will help surgeons gain more confidence

Dr. Kieval strives for zero

Dr. Gulani reports that he is a consultant/speaker for Oculus, Marco, Ocular Therapeutix, EyePoint

1. Gulani AC. Corneoplastique. Art of vision surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014;62:1:3-11.

2. Lee BS, Chang DF. Comparison of the rotational stability of two toric intraocular lenses in 1273 consecutive eyes. Ophthalmology 2018;125:9:1325-31.