One of the most common diseases seen by cornea specialists is dry eye. The telltale signs of redness, irritation, foreign body sensation and tearing are recognizable to these trained professionals, and there’s no shortage of patients seeking treatment. However, there are instances when a patient doesn’t respond to traditional dry-eye therapy or develops severe symptoms practically overnight, suggesting there’s something else going on. Cornea specialists are challenged by rare conditions, including autoimmune and infectious diseases, that can manifest as ocular surface problems, and must play detective to determine the root cause and best path forward to bring relief to these patients—many of whom were unaware of their actual disease. Here, they tell us about some of the conditions and how to recognize them.

Autoimmune Diseases

Dry eye itself hasn’t been classified as an autoimmune disease, although some have tried to make the connection, hypothesizing that it’s a localized autoimmune disease caused by an imbalance of the protective immunoregulatory and proinflammatory pathways of the ocular surface.1 It is, however, associated with Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Then there are the ones cornea specialists don’t come across as often.

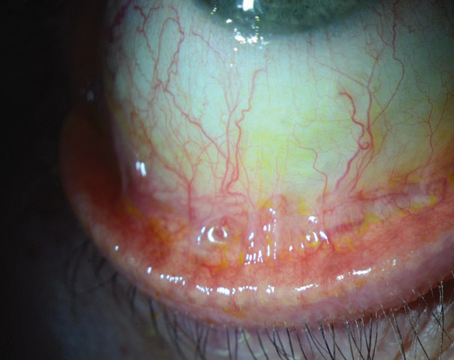

|

| A patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome with amniotic membrane covering the complete ocular surface and lid margins after trimming of all lashes and symblepharon ring in situ. (Courtesy Hall Chew, MD) |

• Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These are immune-mediated, mucocutaneous diseases that can be severe and potentially lethal. Ocular involvement occurs in a vast majority of cases, and if not caught and treated in the acute phase, can result in corneal blindness.2

SJS/TEN can be triggered by medications within the first few weeks of administration. “In severe cases, acute SJS is a severe allergic reaction to drugs such as antiepileptics, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, antibiotics, or unknown etiology,” says Clara C. Chan, MD, FRCSC, FACS, an associate professor at the University of Toronto Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences. “The patient experiences sloughing of their skin throughout the body like a third-degree burn and mucosal membranes can be affected to a severe extent that their airways can be impacted and patients need to be intubated. Very sick patients may be admitted to the ICU or a burn unit for systemic care. Ocular involvement can occur in acute SJS and presents as conjunctival inflammation, lid margin desquamation and severe dry eye. Severity can range from mild to severe and it’s impossible to predict the degree with which patients are impacted.”

The acute phase can vary, but it’s anywhere from a week up to about a month or so. “That’s when there’s active sloughing of the skin,” says Darren Gregory, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, who has extensive experience treating patients with acute SJS. “In the first week or so, at least as far as the eyes are concerned, that’s been shown to be the best opportunity to make a difference. To make a difference you have to cover the edges of the eyelids, the backs of the eyelids and much of the ocular surface or surface the eyeball with amniotic membrane. It’s the most proven treatment to be effective in limiting the damage.”

The fact that patients are routinely admitted to burn units for acute SJS complicates treatment. One survey found that only 66 percent of burn ICUs in the United States consult ophthalmology for SJS/TEN patients.3 “One of the challenges with the amniotic membrane is that it needs to be done relatively urgently,” Dr. Gregory says. Ophthalmology needs to be consulted during the admission process, he adds.

“When I first get called about a patient I want to know how long ago the symptoms started, particularly in the eyes,” he continues. “This allows me to determine for myself if I need to start talking to the operating room to arrange for urgent surgical time. I also want to know the age of the patient. It tends to behave a little less predictably in patients over age 50. I think it tends to follow a fairly fulminant sort of explosive course in young patients, whereas in older patients, they may have other debilitating illnesses so it can sometimes be a little more of a smoldering disease rather than explosive. I also want to know what the skin tone or the race of the patient is, because patients with darker skin pigmentation tend to have more significant disease in the acute phase. So knowing their age, the onset of symptoms and their race helps determine my initial level of concern. I also want to know if they’ve identified a triggering medicine, particularly one called Lamictal (Lamotrigine) that’s frequently used to treat bipolar disorder. There have been published reports that it tends to lead to more severe cases. Allopurinol and sulfa antibiotics are also notorious triggers. I ask all those questions to kind of get a sense of the level of urgency and assess how likely it is that we’ll be surgically treating the patient.”

Awareness is still needed about the viability of amniotic membrane for these patients, he says. “Even after almost 20 years of experience and multiple publications on amniotic membrane, doctors may not be aware of its effectiveness. They may only inspect the eyes every few days and look for scar tissue formation or adhesions between the lids and the surface of the eye and feel like they’ve done what’s needed,” Dr. Gregory says.

Instead, ophthalmologists may initially instill artificial tears, to the patient’s detriment. “They may inspect the patient every few days to look for the formation of symblepharon, and they’ll often start a patient on some form of antibiotic and corticosteroid drops,” says Dr. Gregory. “There’s some evidence that topical corticosteroids help, but they’re not sufficient by themselves if you’re trying to minimize long-term scarring sequelae.”

Dr. Gregory has published criteria for grading the severity of SJS.4 “In our published case series, we described varying disease severities: mild; moderate; severe; and extremely severe categories of involvement based on these factors:

- How extensive is the sloughing on the epithelium along the edge of the eyelids;

- How extensive is the sloughing on the conjunctiva lining the backs of the eyelids and the surface of the eye; and

- Is there any sloughing of the corneal epithelium?

“If more than one-third of the lid margin is sloughed that’s considered severe,” continues Dr. Gregory. “Other criteria for being severe are if there’s more than 1 cm of diameter area of conjunctival sloughing; if there’s any sloughing of the cornea, other than punctate staining; if there’s an actual discreet epithelial defect on the cornea—all of those we found to be concerning features that should certainly increase the level of intensity of care, meaning that urgent amniotic membrane and not just the Prokera AM should be arranged.”

Dr. Gregory says Prokera is like an amniotic membrane contact lens. “It’s useful for treating a number of ocular surface problems, and it can be part of the treatment process in Stevens-Johnson syndrome if the sloughing of the bulbar conjunctiva isn’t extensive,” he explains. “It can be used on the cornea and adjacent conjunctiva, but you also have to treat the back surface of the lids with amniotic membrane or else these patients can still end up with severe scarring problems that lead to the cascade of longer-term visual consequences.”

After the first month, patients enter the sub-acute phase where they’re back home and recovering and no longer critically ill. However, the eyes continue to deteriorate and the effects of all the sloughing and inflammation and early scar tissue formation tend to continue if nothing has been done about them early on.

Dr. Gregory says antibiotics aren’t generally continued in this phase if there weren’t any corneal epithelial defects, but a topical steroid, such as fluorometholone, for longer term treatment may be used due to its lower risk of affecting eye pressure. “If the dry-eye symptoms are improving, we will taper off of steroid drops over the course of a couple of months,” he says. “And we usually have them on cyclosporine drops of some form as well, although the data on whether or not that has an additive benefit in Stevens-Johnson syndrome is probably lacking, but certainly there’s a long history of it being used as a treatment for dry eyes in general. We’ll continue the cyclosporine drops indefinitely if they continue to have dry-eye symptoms.”

Dr. Chan says long-term management of these patients requires chronic control of ocular surface inflammation, aggressive multimodal treatment of dry eye and lid margin disease, and scleral contact lenses to protect the corneal surface from mechanical trauma caused by lid margin keratinization. “Patients with limbal stem cell deficiency and/or severe conjunctival scarring/symblepharon formation and conjunctival deficiency, may be candidates for limbal stem cell transplantation surgery and/or mucosal membrane grafting onto the lid margins with systemic immunosuppression,” she says.

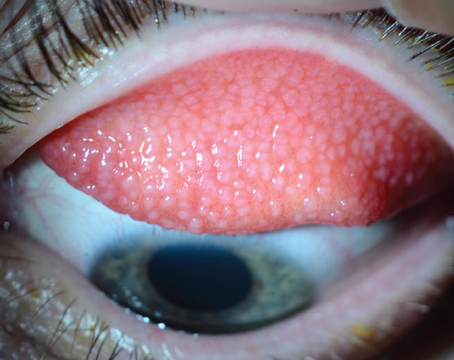

|

| In this stage of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, symblepharon is evident and cornea specialists say a biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any differential diagnoses. (Courtesy Peter Y. Chang, MD) |

• Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. If SJS can be likened to a hurricane blowing through quickly, leaving a trail of damage, then ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is a slow, urban decay, explains Dr. Gregory. “In ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (also referred to as mucous membrane pemphigoid), there’s a slow, smoldering burn of inflammation in the deeper layers of the mucosal epithelium. But the end result after years of untreated OCP can be almost identical to someone who had a severe case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome years before.”

Peter Y. Chang, MD, FACS, who is the co-president and partner of the Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institution, says his is one of the highest referral centers in the country for OCP.

“OCP is an autoimmune disease that’s commonly thought to affect an older population—usually people in their 60s and above,” says Dr. Chang. “In our experience, it’s often discovered by an astute oculoplastic surgeon who received a referral for entropion, only to discover that the entropion isn’t from involutional changes but conjunctival scarring. The scarring (symblepharon) can take months to years to form, although a severe bout of inflammation can lead to its sudden formation. Many times, these patients have low-grade, chronic conjunctivitis that never goes away. Unlike viral pink eye, which comes on suddenly with the eye changing to a pink or reddish hue with a mucous discharge, in OCP patients the inflammation could be really low-grade to the point that they don’t generate a lot of discharge. That’s probably the most common presentation for these patients to complain of typical dry-eye symptoms, irritation and light sensitivity. They get treated with all of the various dry-eye modalities but they don’t respond well and they sometimes get written off as having severe dry eye and are expected to live with it.”

Ophthalmologists must be on high alert if patients with refractory dry eye syndrome have failed most known therapies, Dr. Chang advises. “An ongoing, underlying systemic inflammation must be considered. ”

If not treated properly, OCP patients end up having extensive scarring on their conjunctiva turning their eye inward, causing their eyelashes to start scratching the cornea. “They can get a corneal abrasion that doesn’t heal very well, and this often can rapidly progress to a corneal ulcer,” Dr. Chang says. “Corneal blindness is ultimately how OCP patients lose their sight, unless a corneal transplant is performed. However, human corneal transplant often doesn’t fare well in OCP patients, and an artificial corneal transplant (keraprosthesis) may be needed.”

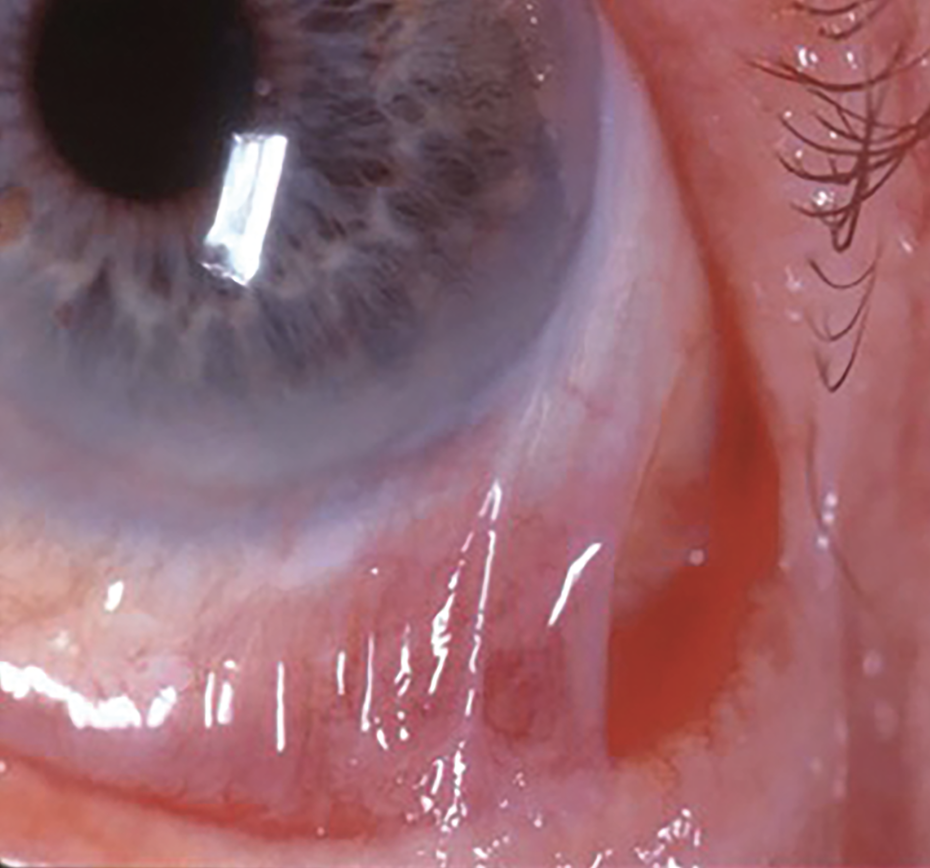

|

| This image shows whitening of the forniceal conjunctiva due to subepithelial fibrosis from ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and demonstrates the importance of pulling down the lower lid to inspect the palpebral conjunctiva and fornix for signs of disease activity. (Courtesy Darren Gregory, MD) |

Once a symblepharon is noted, patients should be sent for biopsy. “We’ll try to ensure that the piece of tissue removed contains at least 50 percent normal conjunctiva as well so that the pathologist can identify the transition zones,” says Dr. Chan. “The tissue is sent in Mitchell’s media so that immunofluorescence staining can be done to identify antibody deposition in a linear fashion on the basement membrane zone. A biopsy of any oral mucosal lesions can also be helpful since the sensitivity of immunofluorescence can be very low.”

Dr. Chang concurs that a biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. “Once we find [the particular antibody deposition] we’ll recommend systemic therapy,” he says. “This isn’t something you treat with topical drops only because there’s not a whole lot that you can do other than chronic topical steroid drops and we all know it’s not good to use those on a long-term basis. It can also put these types of patients at higher risk of infection especially with trichiatic lashes constantly threatening the integrity of the epithelium. We put these patients on systemic immunosuppressive therapy, ranging from oral anti-metabolites to biological infusion therapy. You want to suppress a systemic hyperactive immune response.”

A biopsy can also rule out or identify patients with severe atopic disease. “Atopic diseases can look just like OCP, and sometimes we find they have both the pemphigoid antibody on their conjunctiva and atopic features as well,” says Dr. Chang. “For OCP, taking a good medical history is also important because sometimes these patients also have skin manifestations or other mucous membrane involvement, not just in the eye. You should ask them about voice hoarseness because sometimes they have blisters in their vocal cords. I’ll ask about dysphasia (difficulty swallowing) because of blisters in the esophagus. I’ll ask about blisters in their mouth and tongue. I ask them if there are any blisters or skin sloughing because all of these could be a manifestation of pemphigoid. We have patients who have blisters in their nasal pharyngeal cavity, causing chronic nosebleeds. Many of them are seeing an ENT for these issues. Dentists are often among the first to notice these symptoms.”

Ocular rosacea could also lead to cicatricial changes and is among the many differential diagnoses of OCP, which also includes Stevens-Johnson, sarcoidosis, gonococcal and trachoma conjunctivitis, and even a severe bout of viral conjunctivitis. “Taking a good look at medication history is also really important because there’s a so-called pseudo-pemphigoid,” Dr. Chang says. “You can get cicatricial conjunctivitis just from a toxic reaction to prostaglandin drops, for example. You have to play detective and if you don’t ask, the patients aren’t going to tell you.”

OCP is a chronic disease that needs immunosuppressant therapy, which can take six to eight weeks to work. “We’ll give them topical steroids in the bridging period to systemic therapy,” notes Dr. Chang. “Once the systemic therapy is on board for several weeks to a month or two, we start weaning the patients off the topical steroids. We generally recommend getting the patient on immunosuppressive therapy so that their eyes are completely quiet—no mucous discharge, irritation or redness. Now it gets tricky because sometimes these patients have eyelashes turning inward, so even after you get the inflammation under control, it’s not like the eyelash is going to unturn itself, because the scar is already there. What happens is these lashes can still cause problems, so there’s a lot of upkeep for some of these patients, especially if we diagnosed it later in the game.”

Lubricating the eye is part of this upkeep, he continues. “Start patients on artificial tears and dry-eye medication such as Restasis or Xiidra. You also have to see patients pretty frequently to pull their eyelashes. These patients are slightly older so it’s taxing to have family members taking them to these appointments. It’s important to have family/social support,” says Dr. Chang.

Dr. Gregory says closely inspecting the eye in both SJS and OCP is an important step. “Pull the lower eyelid down and take a look at the backs of the eyelids and into the fornix because there can be a lot of hidden inflammation or sloughing there,” he says. “In SJS, if you don’t look there, you may not recognize that the case is actually more severe than you thought. In pemphigoid, early subepithelial fibrosis in the inferior fornix with whitening of the pink mucosal skin that lines the backs of the eyelids can occur and can be an early tip off that this isn’t just dry eye. It only takes a few seconds just to pull the lid down and have a look. You may see changes that suggest pemphigoid. The importance is that, for pemphigoid in particular, there are very effective systemic treatments, the most effective of which is rituximab, that can halt a lot of the immune activity that’s leading to the scarring.”

• Sarcoidosis. This is an autoimmune, multi-organ disease, and Dr. Chang says the eye is affected 20 percent of the time. “That 20 percent doesn’t mean it’s necessarily vision-threatening,” he says. “Some patients just have dry eye because the lacrimal gland is involved, but there’s a pretty decent subset who may require systemic therapy.”

Sarcoidosis can cause chronic conjunctivitis, and it doesn’t always cause cicatrization, but it could, if left untreated,” he continues. “Sarcoidosis infrequently causes conjunctivitis, but can cause inflammation in any part of the eye. It can cause problems in the lacrimal gland. It can cause problems in the optic nerve, it can cause neurosarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis can affect practically any tissue in the body. As far as the ocular surface is concerned for sarcoidosis, it tends to be a little easier to treat and more responsive to traditional dry-eye treatment.”

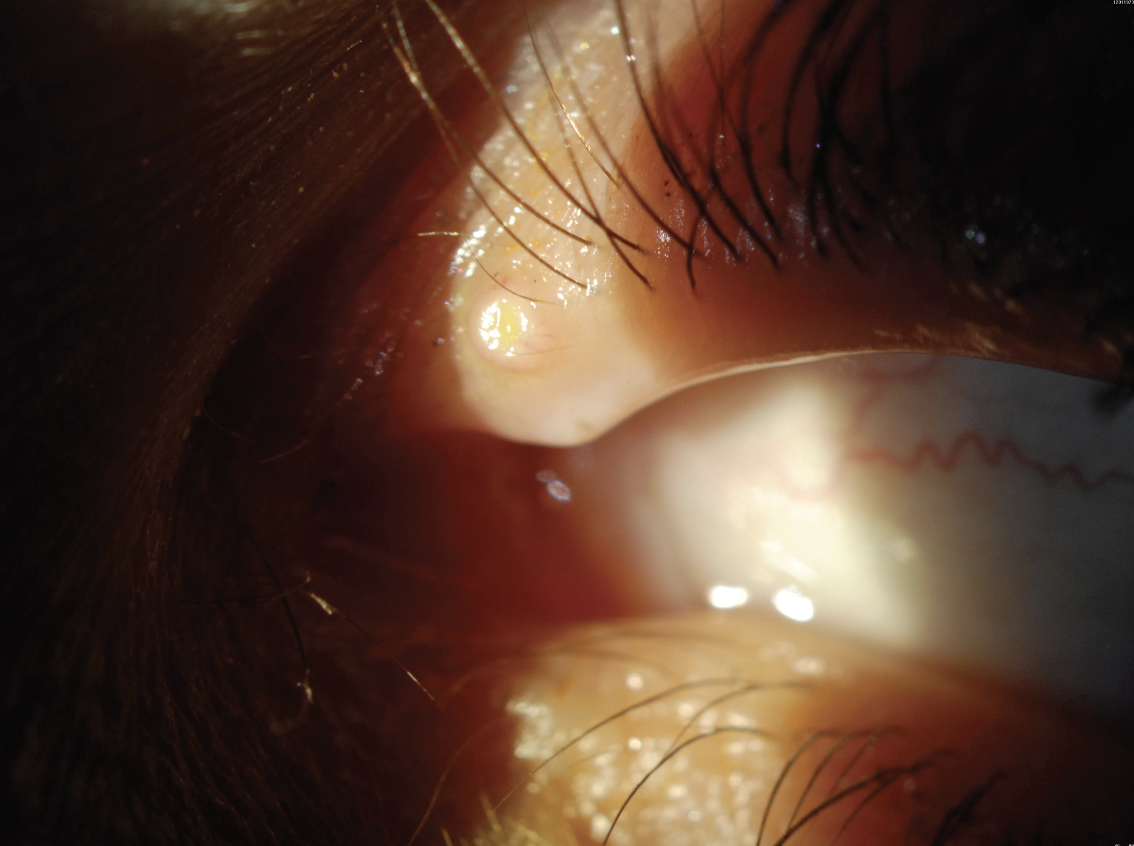

|

| In molluscum contagiosum, a viral wart is usually found on the eyelids and can cause severe follicular conjunctivitis. Patients often go misdiagnosed and receive ineffective treatment. (Courtesy Christopher J. Rapuano, MD) |

Infectious Diseases

Just as autoimmune diseases can be tricky to identify and diagnose, there are a number of unique infections and syndromes that could be misdiagnosed or puzzling.

• Gonococcal conjunctivitis. Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, chief of the cornea service at Wills Eye Hospital, says this is rarely seen at Wills, despite it being a tertiary care ER and infectious disease center.

“It’s classically a hyper-acute type of conjunctivitis, so patients get mucopurulent discharge,” says Dr. Rapuano. “You see pus coming out of their eye, you wipe it away, you look at their cornea, you go to type in your notes, and five minutes later the pus is back again. If you get that you have to suspect gonococcal conjunctivitis. You have to look at the entire cornea because sometimes the lids are so swollen and there’s so much mucous that you can’t get a good view. You may think it looks OK, even though you didn’t see the whole cornea. But if there’s a scratch on the cornea, that can ulcerate very quickly and perforate within 24 hours. Often it’s at the top of the cornea, so if the lid is swollen and the patient won’t look down because the eye hurts, this will prevent you from seeing the superior cornea.” Dr. Rapuano says you may have to consider examining the patient under general anesthesia.

Relief from these symptoms could be fairly quick with appropriate treatment, within a couple of days. “GC requires systemic antibiotics,” according to Dr. Rapuano. “If the cornea isn’t involved, they get a single dose of intramuscular antibiotics, usually 1 g of ceftriaxone. If it does involve the cornea then they get intravenous ceftriaxone for three days. During the acute phase, they’re put on topical antibiotics and that usually helps a lot. The prognosis is very good if you treat them before they have a corneal ulcer. Once a corneal ulcer occurs, then the prognosis is guarded. Corneas can end up perforating, sometimes quickly. They can go from no scratch to an ulcer in 24 hours. For most bacterial infections, it takes days for things to go bad. In this case, if you miss the diagnosis, the patient could be in big trouble.”

• Molluscum contagiosum. This is a viral wart, usually found on the eyelids, that can cause severe follicular conjunctivitis. “The eye could just be red and inflamed, and it can be one eye or both eyes,” says Dr. Rapuano. “Patients typically are treated for blepharitis or allergy with steroids and not getting better. You have to look for these viral warts which can be really small on the eyelid or the lid margin, and they can be hidden within the eyelashes. It’s not an active conjunctivitis, but an allergic reaction to the viral particles that fall into the tear film from the wart. Once you get rid of the wart, the eye gets better.

“You can treat the molluscum lesions a bunch of different ways,” he continues. “You can scrape it until it causes bleeding, cauterize it, do a shave biopsy, do cryotherapy. Many treatments work, but it takes probably about four to six weeks for the redness to go away completely.”

• Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. The symptoms of SLK are often typical ocular surface dryness, irritation, redness, foreign body sensation, pretty nonspecific symptoms, says Dr. Rapuano. “When you encounter patients with these chronic ocular surface complaining symptoms, it’s important to consider SLK. The way to diagnose it is to have the patient look down and examine their superior bulbar conjunctiva and in SLK there’s this leash of red, inflamed tissue. Put some fluorescein on the eye or lissamine green or rose bengal, and it’ll light up. If you don’t have the patient look down and pull the eyelid up to see the white part of the upper lid, you’ll miss the diagnosis every time,” he says. “It’s typically treated with a stepwise approach with lubrication and anti-inflammatories, and you could do cautery to that area to tighten up the tissue or surgery to remove some of that loose tissue.”

• Toxic soup conjunctivitis. This may not be a common term, but it’s a nickname coined by Dr. Chan and colleagues to describe a disease process whereby patients can complain of tearing and present with often unilateral (but can be bilateral) conjunctivitis and papillary reaction on the inferior palpebral conjunctiva along with punctal stenosis or punctal obliteration.

“The poor tear outflow mechanism leads to pooling of inflammatory mediators (from topical medication toxicity, untreated blepharitis, rosacea-related advanced meibomian gland dysfunction, etc.) and nasolacrimal obstruction is ruled out by irrigation,” she says. “The conjunctivitis can come on quite suddenly if the punctal occlusion or downstream canalicular narrowing developed in an acute fashion, for example, after a bout of severe epidemic keratoconjunctivitis or due to sudden migration of a punctal plug downstream.”

To diagnose this condition, examination of the puncta is crucial, as is looking for the papillary changes in the inferior palpebral conjunctiva. “In advanced untreated cases, patients have even developed limbal stem cell deficiency due to the chronic inflammation leading to destruction of the limbal stem cell niche,” says Dr. Chan. “The punctal opening could be covered by a membrane, narrowed to less than 0.3 mm or completely scarred over. Dilation and irrigation through the puncta can be diagnostic (to rule out nasal lacrimal duct obstruction) and therapeutic.”

Identification of the etiology for the pooled inflammatory or toxic mediators is important so that the ocular surface environment can be optimized and the toxic agent discontinued (example, topical glaucoma drops with preservatives), she continues. “Topical steroids and steroid-sparing agents (cyclosporine, lifitegrast, tacrolimus) are crucial and some patients may need long-term maintenance with dilute compounded preservative-free topical dexamethasone 0.01% once to twice daily,” says Dr. Chan. “Lid margin optimization (hot compresses, thermal pulsation, intense pulsed light therapy, lid hygiene, Demodex eradication, antibiotic steroid pulse therapy to the lid margin, etc); oral tetracyclines to treat rosacea; and treatment of lid eczema and atopic keratoconjunctivitis are all crucial.

“However, the underlying problem must be addressed,” she continues. “If a membrane is noted to have grown over the punctal opening it should be peeled away or punctured with dilation and irrigation of the puncta with a 27- to 30-ga. cannula. Referral to oculoplastics may be needed if the puncta scars closed again and a punctoplasty (3-snip) procedure can be done to maintain patency more permanently. More aggressive dilation and irrigation can also help if there’s downstream canalicular blockage.”

• Mucous fishing syndrome. “Patients with this problem will have symptoms of red eye, irritation, itching, tearing and mucous discharge. They develop a habit of picking out the mucous multiple times a day, traumatizing the inferior bulbar and palpebral conjunctival,” says Dr. Chan.

“In this scenario, a patient may get something in their eye and they feel it causes a scratch on the cornea so they keep poking at it to make it feel better, and they realize the poking helps it feel better,” Dr. Rapuano explains. “When the initial problem has healed, the poking is now the problem. The poking is causing scratchiness and it’s a vicious cycle because it feels worse, they poke more, it feels good, it feels even worse and they poke even more. So it’s hard to diagnose because people don’t tell you that they’re doing it.”

To diagnose these patients, doctors will often observe their picking actions firsthand. “Sometimes they just do it right in the office while you’re writing your note,” says Dr. Rapuano. “You look at them and they’ve got a Q-tip, their finger or a tissue in their eyes poking at it. If you ask what they’re doing, they say ‘I’ve been doing this for weeks and it’s not helping.’ ”

Dr. Chan says you can also confirm the diagnosis with fluorescein staining to reveal erosions on the inferior bulbar and palpebral conjunctival surfaces.

“To treat these patients, they need to be educated about the importance of discontinuing the fishing action,” she says. “A course of topical antibiotics and steroids also is needed. Lubrication or rinsing out the accumulated mucous may also provide some relief.”

• Medicamentosa and anesthetic abuse. Medicamentosa is caused by patients who have been on an abundance of medications, says Dr. Rapuano. “They started off with a problem, pink eye for example, and they were prescribed medications but it wasn’t getting better, so they got other medications, then others,” he says. “Eventually, the pink eye has come and gone, but now the patient has so much toxicity from the medications that you can’t tell what’s going on. You need to ask what medications they’ve been on and how long they’ve been taking them. Sometimes I say stop everything except for preservative-free tears and come back and see me in a few weeks.”

Anesthetic abuse is an offshoot of medicamentosa, he continues. “For instance, if a patient has a scratched cornea, they go to the ER because it hurts, and they get a drop of anesthetic and it takes the pain away instantly,” says Dr. Rapuano. “But then the pain comes back after half an hour. So sometimes people will steal the eyedrops from the ER or the doctor’s office and dose themselves every half hour, but then the effect is reduced to 20 minutes, then 10 minutes, and before they know it, patients are using drops every five minutes and it’s causing significant problems. So if you see ocular surface issues that aren’t resolving, you might want to think about this.”

Final Pearls

“Millions and millions of people have dry eye, but not all dry eyes are equal,” concludes Dr. Chang. “When you encounter a more refractory case, you want to consider a potential underlying ocular surface inflammation or conjunctivitis as a cause because there’s a reason why their tear film is unstable. If you don’t feel comfortable treating this, then refer to rheumatology for a head-to-toe examination and a cornea or uveitis specialist. And always take a thorough medical history.”

And to ensure no diagnosis is missed, Dr. Rapuano emphasizes to “always lift the lids.”

Dr. Chan, Dr. Chang, Dr. Gregory and Dr. Rapuano have no disclosures on this topic.

1. Stern ME, Schaumburg CS, Pflugfelder SC. Dry eye as a mucosal autoimmune disease. Int Rev Immunol 2013:32:1:19-41.

2. Metcalfe D, Iqbal O, Chodosh J, Bouchard CS, Saeed HN. Acute and chronic management of ocular disease in Stevens Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in the USA. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021:12:8:662897.

3. Le HG, Saeed H, Mantagos IS, Mitchell CM, Goverman J, Chodosh J. Burn unit care of Stevens Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: A survey. Burns 2016;42:4:830-5.

4. Gregory DG. New grading system and treatment guidelines for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Ophthalmology 2016;123:8:1653-1658.