|

Words to Live By

When I finished my fellowship training, I felt that I was well-trained and had been armed with excellent advice about how to build a practice: Go out and meet other practitioners in the area; communicate with referring doctors and return patients to them; be available to see their patients any time; be nice to patients; and invest some time in making your practice efficient. Looking back, this was all true, and it’s advice that I continue to pass along to all of the trainees with whom I have the privilege of working.

While these are words to live by, however, they’re rather general suggestions, and I would like to provide more-specific ideas. Many times, when asked for advice, experts will give you their top 10 reasons to do something. Since my status as an expert is questionable, I thought I would change things up and give you my top 10 things NOT to do when you are starting out as an ophthalmic surgeon. These may seem obvious, but having them in writing can be a useful reminder:

1) DON’T show off. Picture this: It’s your first week at your practice’s ASC and you want everyone to know that you’re a great surgeon. Even though you probably are great, if your average phaco time is 10 minutes, don’t try to push it and do a five-minute phaco just to show everyone how awesome you are. If you push it, bad things will happen—and then you won’t look so awesome.

Whether you feel it or not, when performing surgery, there’s a big jump from being a supervised trainee to being the one who is fully responsible. Let that sink in as you get back into the groove before turning it up a notch to achieve that five-minute case.

2) DON’T cut corners. During training, many residents and fellows have the luxury of not having to see every patient in a faculty practice. Trainees can spend their time with “interesting” patients who provide educational value, along with more mundane tasks such as suture removal and retinal injections. Then you hit the real world—and every patient that is scheduled to see you is yours. However, we each see patients at a different pace. If 20 patients in a half day leads you to cut corners on patient care, then cut back the schedule until you can increase your or your practice’s efficiency, but don’t cut corners on taking care of your patients. The extra time you spend with them in the beginning will generate the word of mouth that’ll help build your practice in the end.

The same idea goes for surgery. We just talked about not showing off in the OR, but we also inherently don’t want to look like we’re too slow, so we often feel the pull to cut corners here and there. You might instinctively feel that that the wound is most likely watertight, and so you don’t want to have to ask for a 10-0 nylon suture to close it and subsequently take an extra two minutes in the OR. Just remember that those extra two minutes can save hours the next day if you have to take the patient back to put a suture in—or worse, have to deal with an endophthalmitis. If you think you might want to do something in the OR so you’ll sleep better, just do it, and don’t cut that corner.

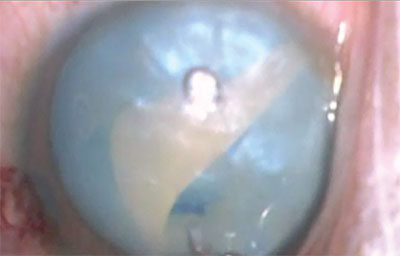

|

| The Argentinian Flag sign—it happens. Remember that you’re human (See tip #9), but just be prepared ahead of time and know what you will do when this occurs. |

3) DON’T forget to be nice to everyone and let them know how much you appreciate them. Yes, you are inherently nice, but when you realize that everything in your practice and ASC is now your responsibility, sometimes the stress can build up until you’re short with—or lose it on—a staff member. If that happens, apologize, because saying you’re sorry can have a very positive effect on people. Yes, you’re now the boss, but always remember that you can’t do anything without your staff: It would take more than twice as long to do surgery if you had to be both the scrub technician and the surgeon. A little appreciation goes a long way and can encourage your staff to go the extra mile for you and the practice.

4) DON’T stop learning. When you complete your residency and fellowship, it’s easy to think that you’ve learned everything you need to know. However, chances are there are things you didn’t have the opportunity to learn in training, and there are definitely things you haven’t seen in your office or done in the OR. As such, you should still seek out opportunities to learn. This is especially true for surgical procedures: as newer techniques evolve, the techniques that you learned in training can become obsolete, and you need to keep up with the times to be able to provide the best care for your patients. I can personally attest to this: The field of cornea has changed greatly in the past decade. For instance, during my fellowship, which was less than 15 years ago, I only did full-thickness grafts, as lamellar keratoplasty was not yet popularized or refined. Now, in most cases for certain indications, lamellar keratoplasty is considered the standard of care. If I didn’t go out and learn endothelial keratoplasty on my own, I’d be in trouble, and I wouldn’t be providing the best care possible to my patients.

5) DON’T lose touch with your mentors. You chose your residency and fellowship for a number of reasons, including the clinical experience you’d get, the faculty you’d interact with and the research opportunities that would be available to you. But it doesn’t end there: Just because you’re done with official training doesn’t mean that they can’t continue to help you clinically or surgically. Though you may worry that you are “bothering” them, or maybe you’re uncomfortable asking them a question that might make them think you weren’t paying attention in training, your mentors should be flattered that you’re still willing to ask them for advice. I still love it when my previous fellows (sometimes from years ago) send me an email asking for tips on how to handle an upcoming surgical case. You can ask many different people, but your mentors are the ones who most likely know you the best and know what you’re capable of doing.

6) DON’T be too proud to ask for help. As in #4 above, you will not have encountered every clinical/surgical scenario during your training, and sometimes, you just don’t know the answer. Being able to admit that you need help can actually earn the respect of patients and colleagues. There are still occasions when I’ll tell patients that I have absolutely no idea what they have, and I’ll even do this in front of the residents and fellows. The patients have all appreciated my honesty and my plan to ask my mentors for advice (See #5), and will eagerly come back during follow-up to ask what I’ve learned to help them. In addition, it’s also a good idea to freely offer patients the opportunity to see another provider for a second opinion; they always appreciate that, and they respect you more for offering. And they’ll be more comfortable with you should they come back to have surgery with you.

7) DON’T forget that you were an amateur at one point.

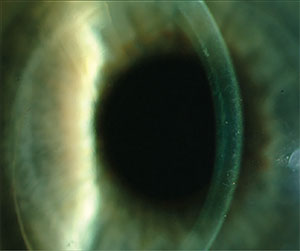

|

| If I only relied on what I learned in fellowship, I wouldn’t have been able to give this patient a great outcome with a short recovery period with endothelial keratoplasty. Don’t stop learning (See tip #5). |

8) DON’T forget that you are human. Though you are no longer the “amateur,” you are still human, and we humans all make mistakes. I was told in residency that if you have never had a complication during surgery, then you haven’t done enough surgery. This is totally true, as even the best cataract surgeons find vitreous every now and again. The important part of this is to recognize your mistakes, then acknowledge them and learn from them. I still encounter tough situations that I think in retrospect about how I might have handled differently, or how I might have done something differently to avoid them. Thinking about and replaying your mistakes will help you be come a better surgeon. Just remember that we all make mistakes.

9) DON’T forget that under the drapes there’s a real, live patient. You may be a super-slick surgeon who can perform 30 phacos per day from the get-go (remembering #1 above), but don’t forget that you originally entered medicine to help people. The people you help have names, and aren’t just disembodied eyes, patient record numbers or “3+ PSC cataracts.” Though it may only be a five-minute procedure to you, remember that the patient may be terrified, and even just a few words of comfort will go a long way toward reassuring him or her.

10) DON’T forget rules 1 through 9. Lest you think that I just ran out of ideas, I actually planned for this particular suggestion. Surgery, ophthalmology and medicine all require a lifetime of learning, and learning requires repetition. So, continuously reminding yourself of rules 1 through 9 will help you be the best ophthalmologist, and person, that you can be. REVIEW

Dr. Jeng is a professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He can be reached at (667) 214-1232 and bjeng@som.umaryland.edu.