The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic plunged the field of ophthalmology—along with the rest of the world—into a sea of challenges, changes and stress. Now that we’re a year into this saga, the initial shock has worn off; people are more able to look at what’s happened with some perspective.

Here, ophthalmologists share three dramatically different stories about how the pandemic affected their practices; what they’ve learned from this experience; and what they believe may happen in the coming months and years. In addition, practice management experts share a few of their observations and predictions.

In the Eye of the Storm

|

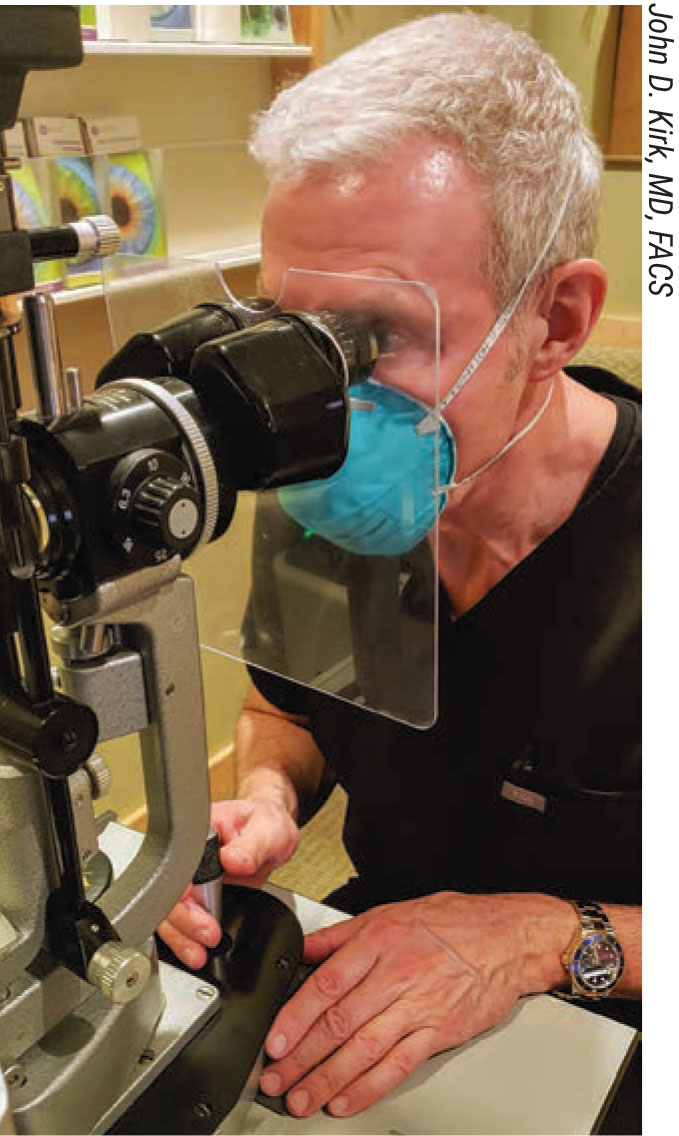

| Practices are likely to leave many safety precautions such as plexiglass breath shields in place indefinitely. |

One of the most remarkable aspects of this is how differently practices in different parts of the country were affected. To illustrate how different those experiences were, we spoke with James C. Tsai, MD, MBA, the Delafield-Rodgers Professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and president of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, who witnessed first-hand the devastation when New York was overwhelmed with the virus; Karl Stonecipher, MD, medical director for Laser Defined Vision and Physicians Protocol in Greensboro, North Carolina, and a clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of North Carolina, who watched how COVID impacted his two very different vision centers; and John D. Kirk, MD, FACS, who practices at the Kirk Eye Center in Loveland, Colorado.

New York City was the epicenter of the pandemic in America for several weeks. Dr. Tsai describes the experience as “harrowing.” “We faced an onslaught,” he says. “It was far more traumatic than what many practices in the U.S. faced—it was more like what happened in Italy.”

Dr. Tsai says the worst month of 2020 was March. “Everything happened all at once,” he says. “I’d been to the American Glaucoma Society’s annual meeting a couple of weeks before the shutdown. Everyone at the meeting was still shaking hands or fist bumping and not wearing masks; no one realized that COVID would be so devastating and so easily transmissible. But the day after I returned from the meeting, the first COVID-positive patient was found in New York. Within two weeks the number of COVID patients exploded.

“What followed happened very suddenly,” he notes. “We were abruptly told that everything was shutting down within the next day or two. So we suddenly had postop patients who couldn’t come in; we had to evaluate them from their homes. Then we started having fatalities. Meanwhile, some of our residents were training at Elmhurst hospital in Queens, and that was part of the epicenter, so our residents were at the front lines in the ER. At the same time, some of our staff, including nurses and anesthesiologists, were redeployed within the Mt. Sinai Health System (including Mt. Sinai Brooklyn) to help care for COVID patients. Our ophthalmologists were helping out in the emergency department. On top of that, there was a shortage of providers because physicians, nurses and staff were getting infected, calling in sick, or were barred from work because they’d been exposed to COVID-positive patients.

“Even by mid-March, when they first locked down New York, we were scrambling to get the appropriate N-95 masks,” he continues. “We had to fight to have ophthalmologists and ear, nose and throat doctors prioritized to get them. After all, we examine patients up close. We had to point out that in China, two of the first doctors affected by COVID were ophthalmologists. It was extremely challenging.”

Dr. Tsai says the next thing that happened was that all elective surgeries were shut down. “Ophthalmology was heavily impacted by this because most of our surgeries are elective,” he points out. “We struggled to find ways to care for patients without seeing them in person. We had to very quickly get creative and ramp up tele-ophthalmology strategies. We had to figure out how patients could download visual acuity charts so they could communicate to us their vision. We got creative about telling patients how to do tactile tonometry. We described to them what their eye should feel like after glaucoma surgery, so they could alert us if their eye felt firm or too soft.

| Will practices recoup their losses? James C. Tsai, MD, MBA, president of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, says he doesn’t expect they’ll make up for all of the patients who postponed or canceled appointments during the pandemic. “Some of our patients have now permanently left New York City,” he notes. “Before the pandemic, people felt that it was ideal to come into the city from New Jersey, Connecticut and Long Island to get health care because there are so many specialists concentrated in Manhattan. Now, New York City has been stigmatized; people see coming here as putting themselves at risk.” Dr. Tsai says this is forcing practices in the city to rethink everything. “We’re looking at partnering with physicians in nearby communities,” he says. “We do have some satellite offices in Long Island and Westchester County, and we’re trying to grow these locations. Our whole strategy has changed.” Karl Stonecipher, MD, medical director for Laser Defined Vision and Physicians Protocol in Greensboro, North Carolina, is optimistic. “I suspect we’ll make back any losses eventually,” he says. “The number of COVID cases has recently been dropping. The more people are vaccinated, the closer we’ll get to ‘herd immunity,’ and the more people will return to our offices.” He suspects that the upcoming months may go very differently for cataract and LASIK providers, however. “I think the cataract market may bounce back, because the people who didn’t get cataract surgery will still need to get it done. On the other hand, fee-for-service offerings like LASIK may be hit hard again.” John Pinto, president of J. Pinto & Associates, an ophthalmic practice management consulting firm, says his average ophthalmologist client practice lost 10 to 15 percent of topline revenue last year, and 25 to 30 percent of normal profits. “That’s obviously an unpleasant experience,” he says, “but it’s not like owning a restaurant and going out of business and walking away from your lease. Almost all independent private ophthalmology practices have stayed in business. Our average client is now back to 80 to 95 percent of historic patient visits and revenue. “Before the pandemic, demand for eye care was going up about 5 percent per year,” he points out. “Everyone’s expectation is that the U.S. GDP is going to grow at least 5 percent in 2021, and unless there are some real surprises with the COVID variants, it would be reasonable to forecast that the trajectory of practice revenue and patient volumes in 2021 will pretty much mirror that. We should be getting back to at least 5 percent annual growth—perhaps closer to 8 or 9 percent growth. I hope that 2021 will be all the time it takes to make up for the step back we took in 2020.” —CK |

“Here at New York Eye and Ear we have busy walk-in eye clinics,” he says. “We wanted to remain committed to that, but we were told that we should reduce our schedules to the smallest number of patients possible, only handling emergencies. So we started a tele-ophthalmology screening service to meet with patients before they even came into our building.

“Then, our revenues plummeted, and we had to furlough our staff,” he continues. “Luckily, the federal government implemented the COVID unemployment supplement, which was applicable for both full and partial unemployment. We ended up working with the state to manage how we handled our staffing crisis. At the same time, we still had to see patients who needed emergency eye surgery. And, we had to get them tested for COVID to keep everyone safe, which was a challenge.”

Dr. Tsai says that through this entire crisis, he and other senior management came into the hospital in person every day. “We knew that a lot of people were feeling despair,” he says. “We wanted to be visible. If the hospital and department leaders are doing Zoom calls from home, that doesn’t engender a lot of confidence. So we managed the hospital and clinics by walking around and being available. We made sure the residents, fellows, attending physicians, nurses and staff knew they were not alone on the front lines.”

Reinventing the Status Quo

Dr. Tsai says the crisis forced them to come up with new ways to handle patients who have become reluctant to come into the city, which is now perceived as risky. “If patients have glaucoma, we may send them to one of our satellite locations outside the city to get their visual fields, OCTs and pressure measurements done by a technician,” he says. “Then, we do a tele-ophthalmology consultation via Zoom a week later. We also don’t want our retina patients waiting around in our very busy retina center and being exposed to COVID, just to be informed that their OCT didn’t show any appreciable change. So we’ve employed a similar strategy in our retina center: Patients come in for their OCT or other retinal imaging; then several days or a week later, they can speak to their doctor via a video visit to discuss whether or not they need to come in for a intravitreal injection.”

Dr. Tsai says the concept of “lean” strategies came to the fore. “The ‘lean’ strategies are all about reducing waiting time and waste,” he says. “Patients of ophthalmology practices spend a lot of time waiting for things like dilated exams and imaging tests. Part of what COVID taught us is that patients don’t want to wait around, especially in a crowded waiting room during a pandemic. So it’s forced us to practice more efficiently to make patients feel safe.

“We realized that even if patients were healthy, they were concerned about coming in,” he continues. “COVID has changed patient expectations. They want to feel safe and they want to feel that we’re taking the waiting-time issue seriously. So, we created videos showing patients what we’ve done to increase safety. The videos show how we clean the rooms between patients, and that our waiting rooms aren’t crowded. We show how we’re using disposables everywhere.

“In essence,” he says, “COVID has forced us to create an environment that’s more efficient and makes the patient feel comfortable about coming in, and then forced us to make sure our patients know about these quality and safety changes. Otherwise, we risk losing more patient visits, which isn’t sustainable when we’re already facing financial challenges because of the pandemic crisis.”

Dr. Tsai adds that one of the lessons they’ve learned is the importance of tele-ophthalmology. “Because of the intense learning we went through, my colleagues and I published a paper about using telemedicine at the height of the pandemic,” he says.1 “In addition to discussing the ins and outs of virtual visits and how these visits may affect the field of ophthalmology, we shared a lot of our telemedicine strategies in that paper—strategies that we’re still employing.”

A Dual Perspective

Dr. Stonecipher, in North Carolina, experienced the consequences of the pandemic from multiple perspectives, because he runs two different practices: One provides cataract surgery, the other laser vision correction. “The laser vision correction practice was part of a chain, but in late March of last year, the pandemic caused the parent company to not only close the practice, but also declare that they weren’t planning to reopen it,” Dr. Stonecipher explains. “They let all the employees go.

“Ironically, this turned out to be a huge opportunity for me,” he says. “I already owned most of the equipment, so I went to the company and negotiated a licensing agreement. I said, ‘I’ll maintain the center if you provide some of the information technology services.’ We agreed that I’d pay them a licensing fee so I could still use their software and call center and keep the company’s name on the door. They agreed, so on May 5th I rehired the majority of the staff—at least as many as I could with minimal patient visits. (We were still seeing mainly postop patients and emergencies because at that time the state still wasn’t allowing elective surgery.)

“By May 12th we were able to start doing laser surgery again,” he says. “Surprisingly, a lot of people still wanted to have surgery, even during the pandemic, because at least in the short run they were getting more money not working than they usually got when working. As a result, a lot of these people had extra income. They wanted LASIK because their COVID masks were fogging up their glasses!”

Dr. Stonecipher says his LASIK center ended up having a good year. “I used PPP money during the first months of the crisis to support the employees that I had,” he notes. “That helped me be able to bring staff back. But this year, in January, when I applied for PPP money again, my accountant told me that we’d done too well in 2020 to qualify. It was partly timing, because to qualify we had to have lost 20 percent of our income in a quarter, and our losses were spread is such a way that no quarter had that big a loss. That was ironic, but I can’t complain when so many other practices had a far worse year than we did.”

Dr. Stonecipher’s other practice offers primarily cataract surgery, and his experience there was quite different. “We separated the cataract business from the LVC business years ago,” he explains. “When the pandemic hit, we furloughed our staff at the cataract center and waited. We continued to pay their insurance. As soon as we could, in mid-May, we brought them back. The governor of North Carolina OK’d performing elective surgery, and we were operating within few days. So by late May we were performing surgery again in both my LVC and cataract practices.

“Initially, on the cataract side, we had numerous patients with second eyes that we hadn’t done,” he continues. “Some patients initially had canceled. As a result, we had a backload from April waiting for cataract surgery. But by June and July, our patients were pretty scared. People were dying; some were stuck in nursing homes and couldn’t get out to have cataract surgery. At that point many people just said, ‘Forget it.’ As a result, I’d say our cataract volume dropped about 20 percent.

“Surprisingly, those people that did come in for cataract surgery were still getting premium lenses,” he notes. “Those who came in tended to be the younger, more mobile population. And, ironically, we also had more new lenses to offer patients, such as Vivity and PanOptix, and I think that helped.”

Changes Made

|

| To get nervous patients to return, practices have made videos and produced brochures like the one above that not only tell patients how to come in safely, but show many of the precautions being taken to protect them, to allay their fears. |

Dr. Stonecipher says he created a new model for managing patients during the pandemic, at both practices. “We focus on protecting the patient by having a safe environment,” he says. “In our laser vision center, when a patient comes in, the waiting room is empty. We take the patient’s temperature and ask the typical COVID questions; then the patient goes into an isolated room and stays there for the rest of their appointment, whether that be surgical or screening, except to go to diagnostics. We were cleaning everything constantly and made sure our patients were aware that we were doing that to protect them. We stopped cyclopleging patients, because we didn’t want them sitting there for 45 minutes. All of these changes reduced the amount of time patients stayed in the office by about an hour and 15 minutes. Ultimately, we made videos with the staff to show our patients what we were doing.

“We also started using different diagnostic tools that were more COVID-friendly to get our information,” he continues. “We now use manifest refraction, wavefront and the DRSplus, which is a nonmydriatic camera made by CenterVue. After evaluation, if the patient says ‘I want surgery,’ everything is done using telemedicine until the day of surgery. All consenting is done online; all payments are collected online using a new autopay system; all scheduling is done online; and all questions are answered via video meetings.

“On the day of surgery, the patient walks in, gets a temperature check, answers a few COVID-related questions and has surgery,” he says. “With the new protocol we average about 48 minutes turnaround time. We’re much more efficient on surgery day, because everything is already done. We also changed our postop protocol. We see the patient in person on day one, but postop week one and month one visits are done via telemedicine. The three-month visit is done in-office, because we want to collect that datapoint. After that, we see the patient at one year. If the patient has no problems, this becomes an annual event. Meanwhile, we’re still giving the patient a lifetime commitment, which is business as usual.”

Dr. Stonecipher says he implemented a lot of COVID restrictions in his cataract surgery practice as well. “You could come in for your surgery, but your significant other could not,” he explains. “If you came in for cataract surgery, I’d see you one hour post-surgery, and that took the place of a day-one visit. The one-week and one-month visits were largely done using telemedicine. However, by August, we eased some of the restrictions; we were back to seeing patients routinely in the office. We’re still doing the postop visit on the day of surgery, eliminating the day-one visit. We still do the one-week, three-month and one-year visits, but now we’ve largely eliminated the one-month visit.

“Of course, we have a hotline for patients who have a crisis,” he adds. “We do a lot of telemedicine with these people. Some have simple issues such as dry eyes or wanting drop refills. Others have specific concerns about their eyes; as much as possible we manage that over video as well.

If patients feel comfortable doing so, they can come in for an exam, but there’s no waiting room any more. In the cataract practice, if you’re not the patient, you can’t come into the office at all unless you have power of attorney and the patient can’t speak for him or herself.”

Farther from the Front Lines

Dr. Kirk’s practice, in Loveland, Colorado, was not pummeled the way practices in New York were. He says his practice has weathered the pandemic pretty well. “Some practices here were closed for an extended period,” he says. “We were closed for two weeks, then partially open for about four weeks after that, doing intravitreal injections and other things we really had to do. But since then, we’ve been completely open. We’re nearly back up to pre-COVID patient volume. So we did better than a lot of practices.

“Of course, we took the COVID safety precautions you’d expect,” he says. “However, we never did telemedicine. It’s been difficult for us to get into that because of very low reimbursement, and we were busy enough seeing patients in-office that we didn’t need to start doing that.”

Dr. Kirk says he believes that in general, the ophthalmologists in his area weren’t hit too hard by the pandemic. “I don’t know of any practice that’s struggling, although we certainly did take a financial hit last year,” he says. “However, we got one of the PPP loans. That allowed us to keep all of our staff on the whole time; we didn’t have to lay anybody off. In any case, we’ve gradually made our way back and built up our volume again.”

One unfortunate reality of the pandemic is that doctors themselves aren’t immune from getting sick. Dr. Kirk says he came down with COVID in October and was out for two and a half weeks, adding to the practice’s financial losses. “It hit me hard,” he says. “I’ve never experienced anything like it before. I wasn’t in the hospital, but I’ve never been so sick. I cleared the virus after 10 or 12 days. Months later, I’m finally reaching my pre-COVID fitness level.

“Ironically,” he adds, “one member of our staff has tested positive multiple times and has never had symptoms.”

Which Changes Will Linger?

To answer this question, John Pinto, president of J. Pinto & Associates, an ophthalmic practice management consulting firm, says it’s worth looking at Singapore. “Singapore has suffered through multiple epidemics over the years,” he explains. “Whenever they have to swing back into caution, out come the temperature guns and masks. They’ve gone through so many on-and-off cycles over the past 15 or 20 years that not only are medical offices well-practiced at this, so is the general society. They certainly don’t think anything about wearing a mask if they have the sniffles, or wearing a mask when walking outside during flu season.

“I think many of the masking and temperature-reading precautions we’ve been taking to deal with COVID are going to stay with us,” he continues. “I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see that, at least during flu season, a lot of practices will have patients wait in the car; or take your temperature before you come in; or ask three screening questions about whether you’ve had a fever or been in contact with anyone who’s had the flu.”

Dr. Kirk points out that the virus could be with us for years. “We’ll probably keep the plexiglass shields at the slit lamp and the reception desk,” he says. “We’re going to wear masks for some time to come, and we’ll be less likely to shake hands with patients than prior to COVID.” He does believe that many COVID safety measures will eventually be removed. “However,” he says, “I think we have to take this in a stepwise fashion. We’ll stop one thing at a time, and remain sensitive to what our patients are expecting.”

Dr. Stonecipher believes many of the changes forced by COVID will remain in place once the pandemic subsides. “We’re much more efficient now,” he notes. “In addition, laws have been changed that have made a difference. Before COVID I wasn’t allowed to contact patients by cellphone. Now, we can text you or your loved ones, and we do. When a patient comes in for LASIK, we call or text the family members to say ‘He’s going in for surgery;’ then, ‘He’s back from surgery.’ Finally we call to say we’re bringing the loved one out. Patients and family members love it.”

Corinne Z. Wohl, MHSA, COE, president of C. Wohl and Associates, a practice management consulting firm based in San Diego, notes that some changes wrought by COVID probably should have been in place all along. “For example, we did a study that found that doctors pre-COVID only sanitized their hands half of the time between patients,” she says. “That’s certainly changed. Smart practices will embed this kind of safety protocol—and especially the visibility of safety protocols—into their routine going forward.”

Ms. Wohl says she believes the COVID experience will also lead to lasting changes in most practices’ attitudes regarding staff taking sick days. “In the past, people felt pressure to not call in sick,” she notes. “Now, if someone isn’t feeling well, they don’t want you anywhere near the office. I suspect this change will remain for some time to come.”

Planning for What’s Next

After a tumultuous year—with plenty of uncertainty about the future remaining—many practices are unsure whether to resume planning for expansion or focus on staying the course. “Planning to expand still makes sense in most instances,” says Mr. Pinto. “However, it’s an individual question. Strategic planning and the growth and development of a business is as much about the personality of the doctor as it is about the opportunities in a particular marketplace.

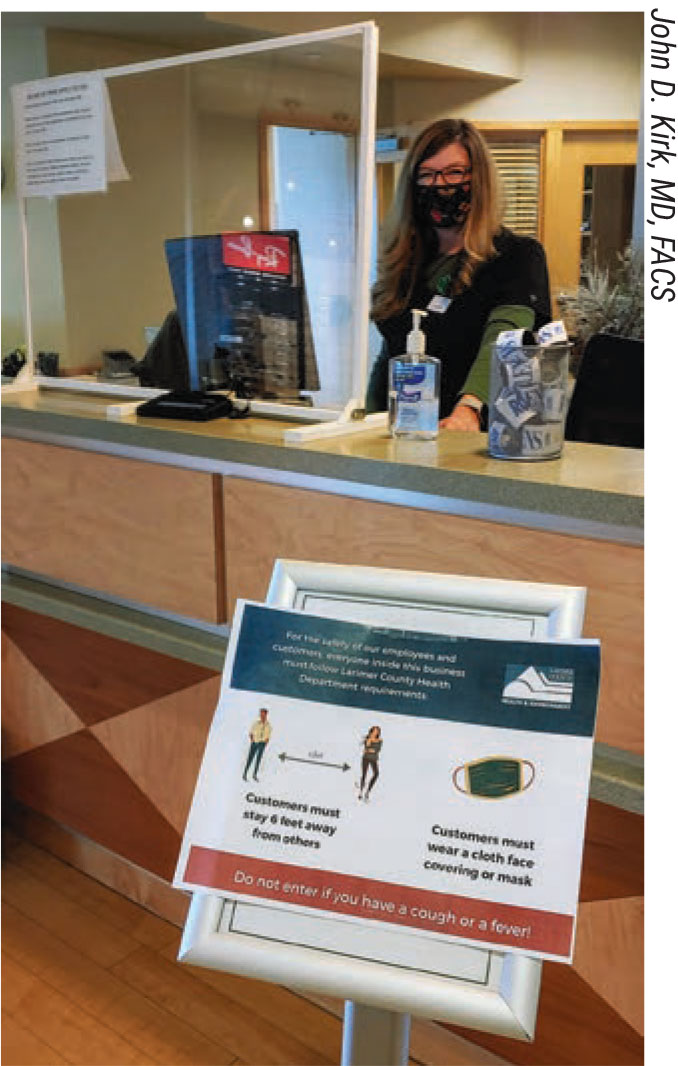

|

| How quickly practices return to crowded waiting rooms will depend in part on how much space is available in the practice to keep patients spread out at full volume. |

“Because of COVID, some clients have had the personal epiphany that life is short and they don’t want to work as hard or build as big as they did before the crisis,” he notes. “Other clients—more aggressive ones—have said, ‘Wow, there are lots of opportunities cropping up in the midst of all of this.’ They say, ‘Let’s take all the energy we put into our pandemic response and put that back into our growth and development plans.’ At the same time, small practices that may have been hit hard by the pandemic might be thinking about becoming part of a larger organization. In fact, we’re seeing a lot of merger and acquisition activity right now.”

“If I was planning to start a practice, I’d go ahead and do that,” says Dr. Stonecipher. “However, these are not normal times. For example, right now we can’t find an OD to hire. My colleagues are saying that there’s a paucity of physician assistants as well.”

“I’m advising clients to pivot from business planning—which focuses on day-to-day and week-to-week urgencies—to longer planning cycles,” says Ms. Wohl. “We’re updating long-range planning documents, helping practices dust them off and move on to better times. In most practices the trauma and fear triggered by facing the unknown with COVID-19 has calmed down. Most of them are going full-steam-ahead with plans to return to their historic norms, and beyond.”

Mr. Pinto says practices should continue to communicate, create written plans and focus on managing projects effectively. “I recently pointed out to a client that he had a task force that was working hard to respond to the pandemic,” says Mr. Pinto. “I told him, ‘Don’t disband the pandemic task force. Just change its name to “the operating committee.” Meet every two weeks and make sure the practice is working as well as it can.’ If you take that new-found energy and apply it to creating the best possible future practice, you’ll emerge from this crisis with the greatest success.

“If a client asked whether they should hold off on growth and development because COVID might rear up again, my answer would probably be no,” he concludes. “There are opportunities now that will sunset after the pandemic is over. So if your plan is to grow and build your practice, now is the time to get back to doing that.”

The Long-lasting Impacts

So what will be the legacy of this crisis? Mr. Pinto believes the most fundamental change wrought by the pandemic has nothing to do with plexiglass shields or empty waiting rooms. “The most seminal component of this is a changed sense of what constitutes a big problem in a practice vs. a small problem, and how we respond to it briskly,” he says. “In the past if you asked an ophthalmologist, ‘What do you most fear?’ the answer would be a comparatively small concern like: What if my favorite lens was no longer available?

“In the context of COVID, those sort of challenges are penny-ante,” Mr. Pinto continues. “This experience has shown how strong and resilient we really are. And, it’s given everyone a kind of vaccination preparing them for the next crisis—whether it’s a tornado, or a building that burns down or a key staff member who leaves the practice. There’ll be a kind of adroitness in responding that wasn’t there before.”

Mr. Pinto says another thing that’s going to stick around is an increased appreciation for the concept of project management. “The response to COVID has been one giant, ongoing project,” he points out. “I think everyone has taken their game up a notch in terms of project management. Clinicians and administrators have become better at collaborating with the appropriate people; writing in-depth plans; nominating leaders; and holding those leaders accountable for outcomes. These skills aren’t going to disappear when the pandemic ends.

“I think the biggest meta-lesson to come from the pandemic is how profoundly resilient ophthalmology is as a profession,” he concludes. “We’ve gotten through this better than almost any other type of service providers, except for people who are making masks and vaccines and PPE. No matter what happens, there are still 650 million eyeballs in America. That translates to an unrelenting market demand for better vision and preserving our sight.”

Dr. Stonecipher is a consultant for Alcon. Drs. Tsai and Kirk and consultants Pinto and Wohl report no financial ties to anything discussed in the article.

1. Saleem SM, Pasquale LR, Sidoti PA, Tsai JC. Virtual Ophthalmology: Telemedicine in a COVID-19 Era. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;216:237–242.