|

Communication Arts

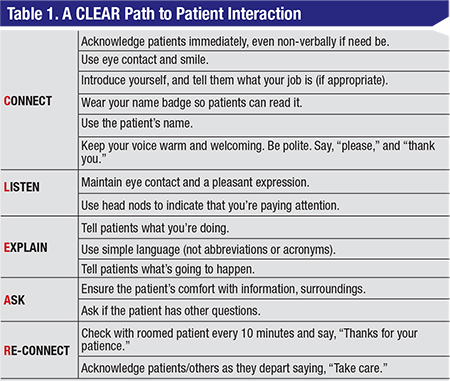

Meryl Luallin, a partner at the SullivanLuallin Group, a firm that helps practices improve the patient experience, says that analyzing the 20 years of surveying has taught her some lessons. “We’re the preferred vendor for patient satisfaction surveys for the Medical Group Management Association, so we have a large database of patient responses,” she says. “After doing a regression analysis of our survey data, we identified the key drivers for both overall satisfaction with a practice as well as the likelihood of recommending a doctor to others. The number-one factor was the provider listening to the patient. Patients feeling listened-to correlates especially highly with a willingness to recommend a practice. The second-highest factor is ‘The doctor had respect for what the patient had to say.’ ” Mrs. Luallin has distilled her learnings about ways to improve the patient experience into the acronym CLEAR, or Connect, Listen, Explain, Ask and Reconnect. (Specific actions that fall under the CLEAR subject areas appear in Table 1, pp. 22.)

Jeff Machat, MD, an anterior segment surgeon in Toronto, says listening to patients is key during an initial consultation about LASIK. “People who are nearsighted will tell you that they don’t have a problem with reading, just with distance, so ‘just fix that and don’t touch my reading ability,’ ” he says. “Meanwhile, we all know that when you get rid of nearsightedness, they’ll then be presbyopic and miserable. It’s important to understand how a patient imagines his life after surgery, and what the procedure’s limitations are, so the result you give him will work for him. We need to have long conversations with people so they really understand what we’re talking about, too.”

|

As part of her job, Mrs. Luallin will shadow doctors at their clinics, or sometimes play the role of a mystery patient, in order to advise them on ways they can improve patient satisfaction. One shadowing session stands out in her memory. “At the beginning of an exam, the middle-aged, female patient told the doctor she had a painful lump in her breast,” Mrs. Luallin recalls. “ ‘When did the pain start?’ the doctor asked. ‘It was in March,’ the patient responded. ‘My mother had died, and then in November my sister died, and my best friend passed away, too. Last year was a horrible year for me.’ ‘Wow,’ the doctor replied. ‘So, when did the pain start?’ This is not uncommon; doctors will tune out all other aspects of the patient interview and just focus on what they need for the diagnosis. It’s the practices who have trained their staff to be caring and come across as personally interested in the patients that score the high ratings.”

For physicians interested in another reason to dislike electronic health records, they need look no further than the cooling effect they have on doctor-patient interaction. It’s hard to be warm and engaging while you’re looking away from the patient and typing data into a computer. Experts say there are some ways to counteract this negative effect, though. “Look at the patient when you speak or ask a question,” says Mrs. Luallin. “Then, as you type, reassure the patient by saying, ‘I’m entering your information into the record, but I’m listening.’ ”

Dr. Machat is aware of the effect of EHR on patient interaction, and takes steps to help mitigate it. “I have both EHR and paper,” he says. “I actually have a scribe in the room, which lets the patient know someone is taking notes and also allows me to focus on him. I always try to put myself at eye level with patients and look them in the eye so they know they have my full attention. Then, once they leave, that’s when I write my notes. So, EHR is amazing and wonderful, but not at the expense of looking someone in the eye and making him feel important.”

Dr. Lee conducted a study of patient-centered care in ophthalmology, with a particular emphasis on patient expectations.1 Part of the paper involved patient focus groups that allowed individuals to identify the most important things they expected and appreciated when they visited the ophthalmologist. “The top desire was for honesty,” Dr. Lee avers. “The second was information about their individual diagnosis and prognosis. Third was receiving an explanation in a clear language. The fourth-ranked expectation involved an issue of skill: The doctor’s reputation and experience. However, the fifth- and sixth-ranked expectations go back to communication and relationships, specifically empathy and how well the practice listened to, and addressed, their concerns. So, five of the top six key expectations involved how well the physician and his staff relate to patients, rather than his or her skills.”

Mrs. Luallin says her firm’s surveys have found an interesting effect of expectations on satisfaction. “An analysis of our database has found that first-time patients rate a physician experience lower than existing patients do,” she says. “We assume this is because existing patients have learned what to expect and have lowered their expectations. As an aside, when we speak to practices and patients about what causes many complaints, the answer is often unmet expectations. We all experience this even outside of medicine, such as when we travel and have bad experiences with a hotel’s service that didn’t meet expectations. The bottom line is, if patients have an expectation and it’s unmet, such as the expectation that the doctor would take some time with them but instead rushed in and out in five minutes, they could be a little bit disappointed, and this will show up in the ratings.”

|

Surgical Satisfaction

Experts say the need for good communication doesn’t stop at the exam lane, but instead continues right to the operating room.

When Dr. Machat was with TLC Laser Eye Centers he says they conducted many surveys and, once again, communication was a key finding. “The number-one factor was the patient not getting the visual result he was looking for,” Dr. Machat says. “He may have gotten 20/30 or 20/25 and felt he paid a lot of money and really wanted 20/20. The number-two factor was having to wait too long. Third was when he felt like just a number, like someone on a conveyor belt. And then in spots four through 10, it was all about human interaction. Oftentimes, these complaints would be that they didn’t feel the surgeon gave them enough time, understood them or listened to them. They’d also complain that the surgeon didn’t talk them through the surgery. So, overall, nine out of 10 issues had to do with interpersonal interactions. This led me to understand that, as a staff member, if you’re having a bad day you still have to muster up a smile. That’s how a patient wants you to feel about their care.”

“There’s a phrase that’s popular in patient satisfaction: Narrate the care,” says Mrs. Luallin. “This involves telling the patient what you’re going to do or are doing as you do it.” Dr. Machat thinks this is key to managing a patient’s trepidation during surgery. “When the surgical patient arrives at prep, I have an amazing staff who will calm him down dramatically,” he says. “They distract him with conversations about his life, and inform him about what to expect during the procedure, going through the steps, and telling him the dos and don’ts. By the time the patient sees me, he’s in great shape. Then, during the procedure, I say the word ‘perfect’ 1,000 times as I describe what I’m doing. ‘You’re going to feel some pressure now … perfect.’ Then, ‘Everything’s going to be dark … perfect.’ I say it so often that when patients sit up and I ask how it was, they’ll say ‘perfect.’ I also have someone count down during every step so the patient knows how many seconds it will take before that step is complete.”

As an example of how effective narrating care can be, Dr. Machat recalls one patient who traveled from New York to Windsor, Ontario, in 1993 to have PRK. “She had a low prescription,” he recalls, “and we performed PRK. I told her during the case that if everything goes right, her vision will be blurry immediately afterward. When the surgery was done, she sat up and started to cry. I asked if everything was OK and she blurted out, ‘I’m so happy—everything is blurry!’ So, it’s all how you speak to patients.”

Ultimately, Dr. Machat thinks one of the keys to satisfied patients is to remember that this is all new to them. “I tell doctors and staff that they have to put themselves in the patient’s shoes,” he says. “You may have done thousands of cases, but this is the patient’s one and only time he’s experiencing this. I want patients to feel comfortable, that they can ask us anything, and to know that we’re empathetic to what they’re going through.” REVIEW

1. Dawn A, Lee P. Patient expectations for medical and surgical care: A review of the literature and applications to ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:5:513-24.