How They’re Made

Preparation protocols for ASED vary, but they all share these fundamental steps: The patient donates blood; the blood coagulates and is centrifuged to extract the serum; and a quantity of serum is placed into a dropper bottle, usually with diluent—often a sterile saline solution. Most drops are 20% serum, although some patients use 25%, 50%, or even 100% serum drops.

Darren G. Gregory, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, spearheaded an ASED program at the University of Colorado Eye Center in Aurora, Colo., now in its second decade. “The patient gets blood drawn at the hospital’s outpatient blood-draw center, and then the inpatient pharmacy centrifuges and prepares the drops. Then the patient can pick up the drops from the hospital pharmacy,” he explains. The pharmacy’s standard dilution is 25%, but the strength can be titrated up to 100% serum.

|

| Patients with limbal stem-cell deficiency undergoing PK are at risk of developing dry eye. Autologous serum eye drops started preoperatively can help prevent this. |

Anat Galor, MD, MSPH, a staff physician at the Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center and associate professor of clinical ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, credits her colleague, Victor L. Perez, MD, with setting up a serum tears laboratory in the Bascom Palmer Ocular Surface Center that makes procuring ASED easy for patients. “I just write a prescription and I send it to the lab, where it’s all done for them,” she says. Dr. Galor says that their standard dilution is 20%, “but we can escalate the dosage up to 50% in our lab, based on effect.”

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, chief of the cornea service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, also typically starts his patients at 20% dilution. “We can go up to about 50%, but there’s no right or wrong on that,” he says. His patients currently get their drops made outside of Wills Eye. Dr. Rapuano calls a designated blood-draw facility to advise that a patient is coming to donate. The blood then goes to a specialized compounding pharmacy in Maryland, which in turn ships the finished ASED to his patients.

The Benefits

To launch an ASED protocol at his hospital, Dr. Gregory had to pitch its potential benefits. “I had to convince a lot of committees that such a program was a viable option,” he recalls. ”We think that the various growth factors and nutrients that are contained in the serum provide a lot of things for the surface of the eye that may be missing when the eye is very dry, or if there is scarring or other abnormality on the surface of the eye. It can often alleviate dry-eye symptoms in patients who have not had good relief from other available treatments. It can also help non-healing corneal epithelial defects,” he explains.

“Dry eye is a huge category,” adds Dr. Rapuano, “including patients with severe ocular surface disease, chemical burns, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.” He tells his patients that ASED contain “goodies” found in the body but unavailable in artificial tears, such as antibodies and growth factor. “It often helps them feel better, see better, and it helps the health of the ocular surface.”

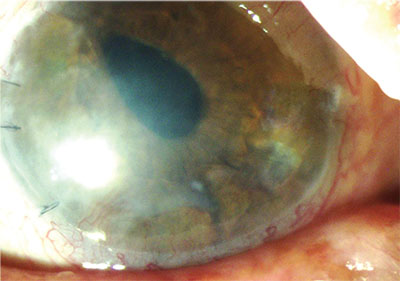

“Whatever the underlying biology is, clinically, they work,” says Dr. Galor. “I’m a total believer in autologous serum tears.” She uses them in patients with neuropathic eye pain, neurotrophic keratitis and for “patients who have a lot of signs of dry eye, such as diffuse staining” that is refractory to traditional therapies. “In those cases, it may be that the density of the serum tears—the fact that they have a lot of albumin—could be coating the eye and driving the beneficial effect,” she says. “Then again, it could be that helping the nerves secondarily helps the epithelium, so that it all comes down to nerve health.” In addition to using ASED before and after certain high-risk corneal transplants and SLET procedures, Dr. Galor prescribes them for post-vitrectomy diabetics. “I also use them in patients when I’m worried about their limbal stem-cell environment,” she explains. “That’s a very specific subtype of dry eye that is not very common, but it’s very difficult to keep the epithelium healthy in those patients.”

Serum contains bioactive agents that may promote healthy cell growth and healing of the ocular surface, including albumin, vitamin A, and nerve and epidermal growth factors. Evaluating evidence regarding the efficacy of ASED is not helped by the fact that sample sizes tend to be small with little follow-up; there is also no universal protocol for preparing and storing the eye drops. Studies have, however, demonstrated instances of ASED surpassing artificial drops in promoting comfort and improving the quality of the tear film.3,4

Sjögren’s syndrome can cause severe dry eye stemming from diminished basal and reflexive tear production.5 Dr. Galor says that patients with Sjögren’s and other autoimmune diseases can benefit from ASED. “There’s always a question regarding patients with autoimmune disease, because they have circulating autoantibodies: Is their blood going to be helpful for serum tears? But we have a very large group of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and graft-versus-host disease, and these patients seem to do well.”

|

While Dr. Gregory counts himself fortunate to offer his patients ASED, he has had to advocate for it. “We’ve squabbled with the hospital committee,” he acknowledges. “The pharmacy was looking at all of their overhead costs—factoring in the cost of lighting in the lab, for example. They did an analysis from start to finish: The blood-draw center had its charge; they figured in a charge for the in-hospital courier who walks the blood from the blood-draw center up to the pharmacy lab where they mix it.” Dr. Gregory estimates that a three-month supply of drops starts at $180 for his patients. “There were times when they tried to raise the price to nearly $300 for a batch, but the patients just aren’t going to be able to pay that,” he continues. “We gave patient testimonials to the various leadership folks in the hospital. We presented them with a number of articles from the medical literature supporting the use of this type of drop. Because we are a big academic center, we try to provide care that is not readily available elsewhere, so they recognized the importance of that. Thankfully, we’ve been able to maintain the program for over 10 years now.”

The Right Patients

While ASED can and do help many patients, they aren’t for everyone. “About half of the patients we try it on seem to benefit and we continue; but half don’t benefit enough to want to continue,” says Dr. Rapuano. “It’s a hassle to get your blood drawn every three, four, or six months, depending on how much they draw, which depends on the percentage of the drops you use.”

Some settings follow blood-donor guidelines that disqualify certain patients from supplying their own blood for the drops. Positive serology test- ing is not an exclusion criterion at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. “We practice universal precautions, and we do not test the blood prior,” Dr. Galor says. “We’ve had good success with patients who have infectious serological markers. Our patients with HIV, for example, seem to do well. We haven’t found specific blood types that are a contraindication to the clinical effect of serum tears; and again, there are very strict universal precautions, no matter who the patient is.”

Prior to the protocol that Dr. Rapuano currently uses for his patients, the lab that did blood draws required testing. “I’m told that’s not required anymore,” he says. “It was always a little bit funny to me as to why that was required, because universal precautions are taken by the people who draw the blood and the people who treat the blood; so whether or not there are infectious components in there, the people handling it shouldn’t ever be exposed.”

Dr. Gregory’s ASED program does not require testing, either. “We haven’t run into trouble. I guess that’s part of the benefit of the rigorous system that we have in our hospital for preparing the drops,” he says. “We have a careful process. There are certainly practices that will prepare them in their own offices for patients, but I think that’s a little riskier.”

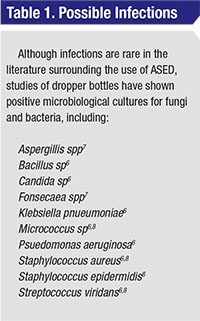

While safe handling of blood products during ASED formulation is critical, so is the safe handling of finished eye drops. Patients must be counseled to store their unopened droppers in the freezer. A dropper in use should be refrigerated to preserve beneficial agents and retard the growth of harmful microorganisms. Although adverse events are rare in the literature, dropper bottles can culture bacterial and fungal contamination.6,7,8 “Theoretically, bacteria could start to grow and patients could be giving themselves bacteria in the eye,” notes Dr. Rapuano. “That’s why they have to take care of the drops and keep them in the freezer before use. We always tell patients there’s a little bit of risk to this, but that we think there’s a bigger risk to the current eye problem we’re trying to treat.”

Logistics and Costs

Not only must patients comply with safe storage and use guidelines to benefit from ASED; they must also follow the steps it takes to obtain drops—several times per year, possibly for years to come. Even though Dr. Gregory’s patients can get their drops made on one campus, that location is the only large academic eye facility in a 500-mile radius, so many travel great distances. “The process is a bit cumbersome,” he says. “The patient has to get the blood drawn, and then there’s usually only one day per week that we have a technician who’s assigned to prepare the drops.” Dr. Gregory adds that shipping is available to patients in Colorado, but patients from Wyoming, Kansas, and Nebraska may need to come back a few days after blood donation to pick up their eye drops.

Last—but certainly not least—on the list of challenges to widespread use of autologous serum is the cost, which is almost always borne by the patient. “It’s cash: Insurance generally won’t cover it,” says Dr. Gregory. “It’s a couple of dollars a day when you add it all up, but when patients pay it up front, it seems like an awful lot of money for some drops.” Dr. Galor estimates that a two-month supply costs about $220. “It’s not cheap,” she acknowledges, but her VA patients are spared out-of-pocket costs. “One nice thing is that the veterans get it paid for,” she notes.

Researchers have attempted to develop uniform preparation protocols that would be accessible, affordable, and replicable in most health-care settings. A paper published in 2011 estimated that ASED cost U.S. patients anywhere from $25 to more than $600 out of pocket for a two- to three-month supply.9 Researchers from Hamilton Eye Institute in Memphis, Tenn., proposed a protocol wherein blood-draw centers would take the lead in serum preparation as well as blood collection. Factoring in the costs of materials and technician time to produce one three-month supply of ASED, they posited an estimated cost of $80, which didn’t include packaging or shipping. Another estimated cost was $82 for annual

serological tests: The protocol excluded patients with markers for HIV, hepatitis or syphilis.

Are Alternatives Coming?

Given the inherent challenges of ASED use, are any other modalities in the pipeline that would confer their benefits without the hassles? Dr. Galor sees two emerging technologies, neither of which replaces autologous serum tears: a preparation kit to make them more accessible to patients; and the potential addition of other autologous blood components to increase their clinical effects. She cites a proprietary kit being developed by a company in Spain that would simplify the production of serum tears. “I don’t have access to it, but I know that it’s being looked at as a way to get the technology out,” she says. “Another area of interest is adding other blood products, such as making platelet-rich serum tears, to make the serum tears more effective. There is still a lot that’s unknown about the best percentages, formulations, and other blood products you may want in there to enhance the effect. Those are some of the things that people are talking about.”

Dr. Gregory notes that Regener-Eyes, a Florida-based company, has made amniotic-fluid eye drops commercially available, and cites plasma rich in growth factors as another potential avenue of dry-eye therapy. His hospital was involved in human trials of an eye drop derived from recombinant bovine albumin. “I’m not sure what became of it,” he says. “We had just a handful of patients using it. We didn’t know if they were getting placebo or the actual medication, so I didn’t have a great sense of whether or not it was helpful. But I think it always comes down to the same problem: None of these treatments, to my knowledge, are currently covered under people’s insurance, so it’s all out-of-pocket and expensive. Unfortunately, nothing has really grabbed hold or become logistically simple or affordable.”

Reflecting on his ASED program, Dr. Gregory remains convinced of its importance to his severe dry-eye patients. “The serum drops, with our preparation protocol, have shown themselves to be a reliable, safe treatment, that, despite the cost and some of the hurdles, has proven very helpful for those who haven’t gotten great benefits from the more readily available treatment options. We’ve been glad to have them for our patients,” he affirms.

Doctors who want this option for their patients need to screen those patients carefully, candidly discussing the financial and logistical burdens that ASED treatment may impose. They can refer patients to appropriate phlebotomy and compounding facilities to have the drops made, or face the formidable task of developing a safe in-house protocol. Educating patients about the safe storage and handling of ASED is also important. Despite this lengthy to-do list, autologous serum eye drops can offer patients with recalcitrant dry eyes—and the suffering that accompanies them—a good measure of bang for the buck, provided they have the money to spend.

“They help a lot of people,” says Dr. Rapuano. “We tell patients that this is an unusual use, and we’re doing it to address an unusual problem.” REVIEW

Dr. Gregory, Dr. Galor, and Dr. Rapuano report no financial interest in any of the products mentioned in this article.

1.Ralph RA, Doane MG, Dohlman CH. Clinical experience with a mobile ocular perfusion pump. Arch Ophthalmol 1975; 93:1039.

2.Fox RI, Chan R, Michelson J, et al. Beneficial effect of artificial tears made with autologous serum in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 29: 577-83.

3.De Pascale MR, Lanza M, Sommese L, Napoli C. Human serum eye drops in eye alterations: An insight and a critical analysis. J Ophthalmol 2015; 2015:396-410.

4.Celebi AR, Ulusoy C, Mirza GE. The efficacy of serum eye drops for severe dry eye syndrome: A randomized double-blind crossover study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014;252:619-26.

5.Tsubota K, Goto E, Fujita H, Ono M, Inoue H, Saito I, Shimmura S. Treatment of dry eye by autologous serum in Sjögren’s syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83:390-395.

6.Leite SC, de Castro M, Alves M, Cunha DA, Correa MEP, da Silveira LA, Vigorito AC, de Souza CA, Rocha EM. Risk factors and characteristics of ocular complications, and efficacy of autologous serum tears after haematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation 2006;38:223-7.

7.Thanathanee O, Phanphruk W, Anutarapongpan O, Romphruk A, Suwan-Apichon O. Contamination risk of 100% autologous serum eye drops in management of ocular surface diseases. Cornea 2013; 32:1116-9

8.Lagnado R, King AJ, Donald F, Dua HS. A protocol for a low contamination risk of autologous serum drops in the management of ocular surface disorders. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 464-5.

9.Partal A, Scott E. Low-cost protocol for the production of autologous serum eye drops by blood collection and processing centres for the treatment of ocular surface disease. Transfusion Medicine 2011; 21:271-77.