Although topical drops remain the first-line treatment for most new glaucoma patients, surgery is often necessary to manage patients in need of major intraocular pressure reduction. For many years trabeculectomy has been the most popular approach in this situation, but that’s slowly been changing.

|

Steven J. Gedde, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, notes that the use of tube shunts for the surgical management of glaucoma has been growing in popularity. “Medicare claims data has shown a clear shift away from trabeculectomy and toward tube shunt surgery,” he points out. “Also, a series of surveys of the American Glaucoma Society membership, starting back in 1996, has demonstrated that tube shunts are being selected as an alternative to trabeculectomy with increasing frequency.

“Historically, tube shunts were reserved for eyes felt to be at high risk for failure with trabeculectomy,” he continues. “That included eyes that already had a failed trabeculectomy, eyes with extensive conjunctival scarring from prior surgeries and eyes with certain refractory glaucomas that tend to do poorly with traditional filtering surgery. The latter group includes eyes with neovascular glaucoma, uveitic glaucoma, iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, and epithelial and fibrous ingrowth; these eyes have been managed with tube shunt surgery for decades. Today, however, the shift has been toward the use of tube shunts in less-refractory patients. Some good emerging evidence even shows that these devices may be appropriate as an initial surgery—even in eyes at low risk of filtration failure.”

Here, surgeons with extensive tube shunt experience share their insights and advice for getting the best outcomes when using these devices.

Choosing the Best Candidates

Like every approach to lowering IOP, the use of tube shunts can be problematic in certain eyes.

“I tend to avoid placing tube shunts in eyes that have very shallow anterior chambers or underlying corneal disease, because there’s a higher risk of corneal edema with tube shunts in these eyes,” says Dr. Gedde. “Corneal edema is usually related to the mechanical trauma that occurs if the tube touches the corneal endothelium, which can lead to progressive endothelial cell loss. In these types of patients I consider a surgical approach other than tube shunt surgery.”

Brian Francis, MD, MS, a professor of ophthalmology in the glaucoma service and the Rupert and Gertrude Stieger Endowed Chair at the Doheny and Stein Eye Institutes, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, says he’d consider a tube shunt if the patient is at high risk for failure with other surgeries, such as trabeculectomy, or at high risk of infection or hypotony. “Tube shunts are also an option for patients who’ve failed to achieve adequate pressure reduction with MIGS procedures, or whose disease is so advanced that MIGS isn’t seen as a good option,” he says. “On the other hand, factors that make someone a poor candidate for a tube shunt include very poor ocular tissues, such as scarred conjunctiva; very thin conjunctiva; corneal endothelial disease; and a shallow anterior chamber, which can result in the tube causing endothelial cell loss.”

|

Choosing the Right Shunt

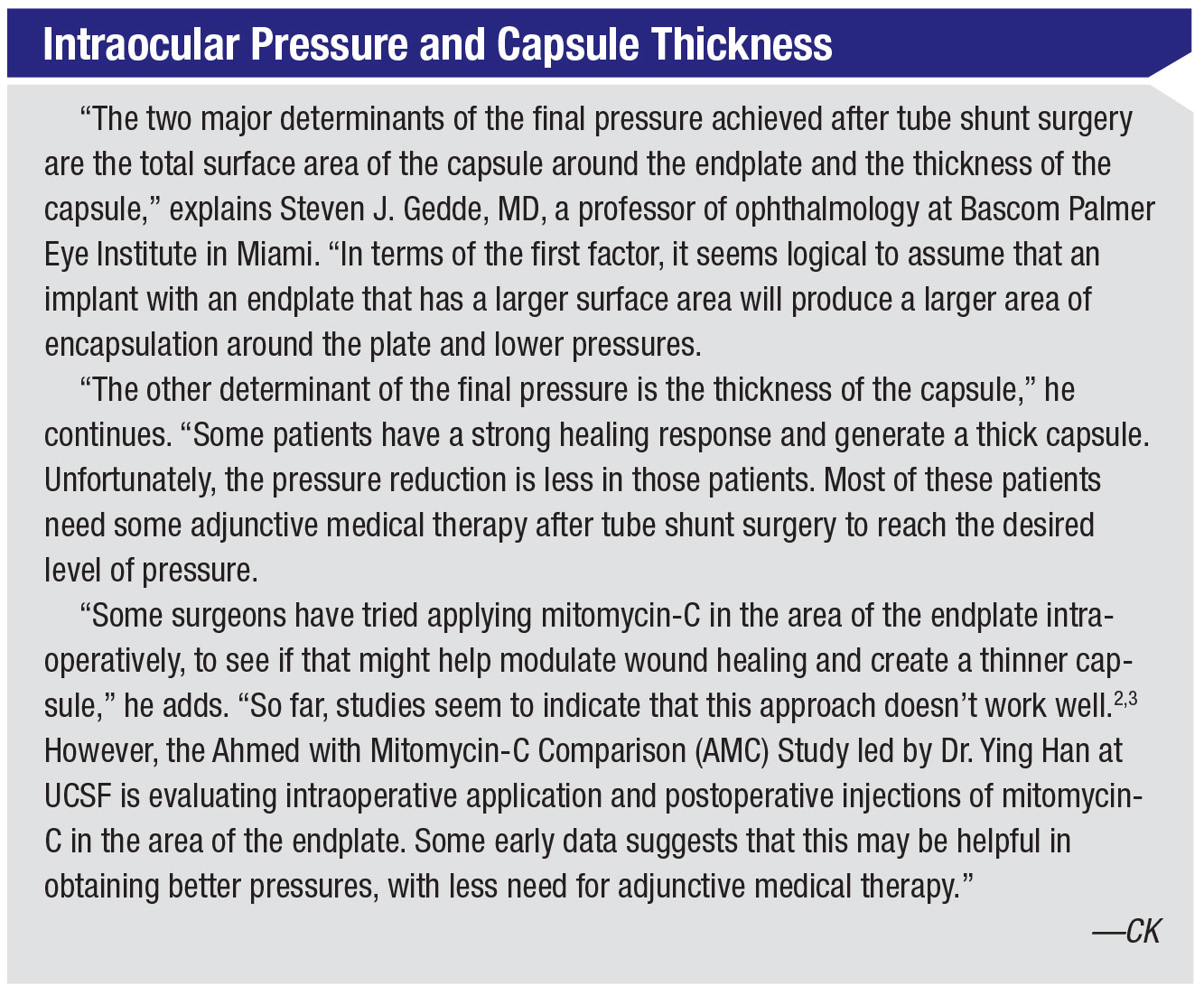

Once you’ve decided a tube shunt is the best option for your patient, the next question is which shunt to implant. Dr. Gedde explains that tube shunts fall into two basic categories: valved and nonvalved. “Valved implants have a flow restrictor that limits aqueous outflow through the device if the intraocular pressure goes too low,” he says. “The advantages of that design include a lower risk of hypotony, and the fact that the implant starts working immediately postop.

“In non-valved implants the major resistance to aqueous flow occurs across the fibrous capsule that develops around the endplate,” he continues. “This capsule must be present before the tube is totally open and fully functioning; otherwise you’ll have hypotony-related problems. For that reason, the surgeon has to restrict flow through the tube at the time of implantation to avoid hypotony in the early postop period.”

Dr. Francis says the surgeon’s choice is usually between a valved implant such as the Ahmed FP7 and nonvalved implants such as the Baerveldt 250 or 350, the Molteno, or the relatively new Ahmed ClearPath 250 and 350. “I use both valved and nonvalved shunts,” he explains. “I tend to use a valved shunt in patients who have high pressure and need immediate pressure reduction but may not need pressure as low in the long term,” he says. “Those patients are good candidates for the Ahmed FP7. If they need lower long-term pressure, I think non-valved implants such as the Baerveldt, Molteno or ClearPath work a little bit better.”

“We know that eyes with uveitic glaucoma often have hyposecretion of aqueous humor, making them more prone to hypotony following glaucoma surgery,” says Dr. Gedde. “A valved implant like the Ahmed FP7 helps to protect against that. A valved implant is also preferred in patients with markedly elevated IOP, when you need reliable pressure reduction immediately after surgery. However, in most cases I prefer nonvalved implants. There’s good evidence that larger-size implants such as the Baerveldt 350 or the new ClearPath 350 provide a greater degree of pressure reduction. These are ideal for patients with advanced glaucoma, and for patients who are poorly tolerant of medical therapy—those in whom use of adjunctive medications is limited.”

“In terms of choosing between the 250 and the 350 models, I base that choice on the severity of the glaucoma,” says Dr. Francis. “In most cases I use a 250, but if a patient really needs a low pressure—which may be the case if the patient has low-tension glaucoma or advanced disease—I’ll use a 350.”

Lauren S. Blieden, MD, an associate clinical professor at the Alkek Eye Center, Cullen Eye Institute, Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston, says she likes to have all options available. “Some doctors only use one device,” she notes. “I like to tailor my choice based on the patient’s needs. For example, a neovascular patient needs to lower pressure very quickly, so an Ahmed FP7 is a perfect tube shunt in that scenario. The procedure is quick, patients tolerate it well and the pressure comes down quickly. This isn’t the kind of patient who needs to end up with a pressure of 9 mmHg; you just need a pressure that’s not 50 mmHg.

“Neovascular glaucoma patients may also do better with Ahmeds than Baerveldts,” she continues. “Some da-ta from the Ahmed vs. Baerveldt trial suggested this, as fewer patients progressed to NLP vision in the Ahmed group, although the study wasn’t powered to check the statistical significance of this observed difference. My experience also has been that these patients tend to do better with the Ahmed FP7.

“In terms of uveitic glaucoma patients, everyone has a personal preference,” she adds. “I like to use a Baerveldt 250 or ClearPath 250 with those patients, and I always use a ripcord suture to have control over when the tube opens.”

Choosing the Plate Location

Another decision you need to make is where to place the plate on the globe. “You should almost always put the plate in the superior temporal quadrant, unless there’s a compelling reason not to,” says Dr. Francis. “Superotemporal placement lowers the risk of exposure, as well as the risk of the patient developing strabismus—which is something not every surgeon realizes. If that quadrant isn’t available, then inferonasal is second-best. Superonasal and inferotemporal are generally the last locations to pick. However, if your patient is monocular, strabismus isn’t an issue. In that situation, my second choice for placement of the primary tube, or for placing an additional tube—assuming superotemporal is unavailable—will be superonasal.”

“When I’m considering tube shunt surgery, I look carefully for areas of scleral thinning preop,” says Dr. Gedde. “Patients with certain rheumatological diseases and those who are highly myopic can be prone to scleral thinning. It usually appears as a bluish discoloration of the sclera, because the underlying choroid is visible. If I see thinning, I’ll avoid those areas. Also, if a radial element has been placed during retinal detachment surgery, I avoid that region. Factors like these can influence our choice of where to place the plate.”

Dr. Gedde adds that it matters how far posterior the plate is placed. “When I’m implanting a 350 Baerveldt, I use a caliper to measure 10 mm posterior to the limbus,” he says. “I make a point of attaching the endplate at that location. It’s important not to allow the endplate to be too anterior, crowding the rectus muscle insertion—at least with the Baerveldt 350, which is positioned underneath the adjacent rectus muscles. That could predispose the patient to having double vision.”

Choosing the Tube Location

In most patients, the tube would be inserted into the anterior chamber, but other options are possible. For example, if the anterior chamber is problematic and the patient is pseudophakic, surgeons may consider placing the tube in the sulcus, posterior to the iris but anterior to the lens implant. Other options include:

• If the patient has peripheral anterior synechiae but the chamber is deep centrally, consider making a peripheral iridectomy. “Significant synechiae can prevent us from placing a tube in the usual position,” notes Dr. Francis. “However, if you make a peripheral corneal incision and perform a peripheral iridectomy, you can insert the tube through the iridectomy.”

• If the patient has no anterior chamber capacity or has existing corneal disease, consider putting the tube in the pars plana. “This might be the best option in this situation,” notes Dr. Francis. “However, this will only work if you perform a vitrectomy, and the vitrectomy has to be very complete. Often, when someone has had a previous vitrectomy, it’s just a core vitrectomy; the vitreous face and anterior peripheral vitreous are still present, so the tube can still become blocked with vitreous. Putting the tube a little farther in may help to clear the vitreous skirt, but the tube can still get blocked. And even if blockage doesn’t occur right away, the remaining vitreous can liquify over time and end up getting into the tube at a later date.

“This option also is somewhat problematic because you won’t be able to see the tube as easily, so you can’t tell if it’s blocked or open,” he adds. “Implanting the tube in this way adds a layer of complexity to the workings of the tube, and to the exam required, but for many patients it’s a great procedure.”

• If an eye has silicone oil inside, put the tube in an inferior quadrant. “This helps in case the silicone oil migrates into the anterior chamber,” explains Dr. Gedde. “Oil tends to float up, superiorly, which could lead to a problem if you put the tube in a superior location. The oil might drain through the tube or obstruct it.”

Inserting the Tube

Dr. Francis notes that there are several ways to insert the tube. “You can tunnel through the sclera or put it in at the limbus,” he says. “Tunneling works pretty well, but the longer your tunnel, the more the tube will tend to angle anteriorly towards the cornea, and that can be a problem. You don’t want the tube touching the cornea, or even near the cornea. Finally, however you insert the tube, make sure it’s well-covered, whether it’s through a scleral flap or a patch graft or through tunneling.”

• Consider creating a fornix-based conjunctival flap rather than a limbus-based flap. “Either way is acceptable, but I find that a fornix-based flap provides better exposure when placing the implant and inserting the tube,” says Dr. Gedde.

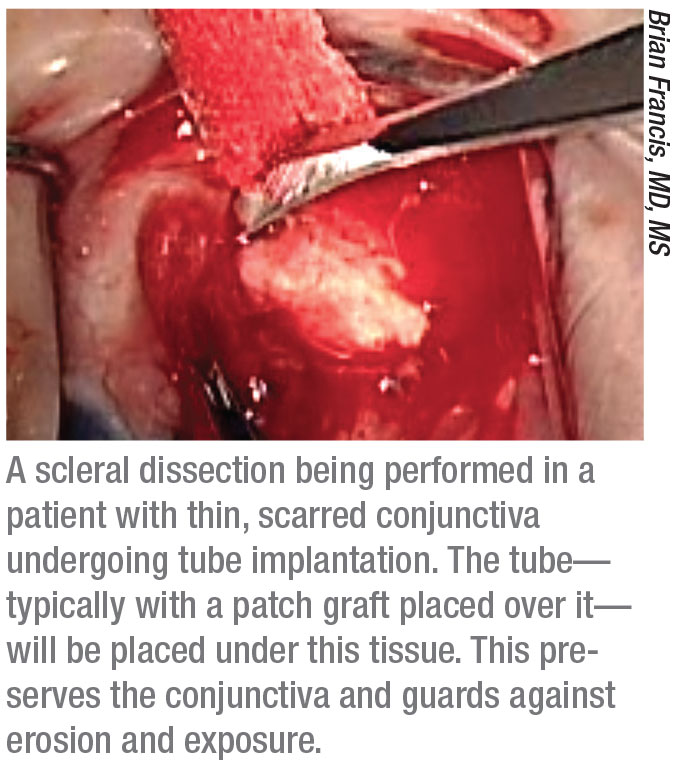

• If the conjunctiva is scarred, consider making a superficial scleral flap. “Many surgeons are afraid to implant a tube if there’s scarring of the conjunctiva or very thin tissue in the preferred quadrant near the limbus,” notes Dr. Francis. “However, you can still put the tube in that quadrant. If the conjunctiva is thin and atrophic and scarred, instead of trying to lift it up, you can make a superficial scleral flap—basically, a scleral dissection. That will get you to the limbus without disrupting the conjunctiva at all. Then you can put your tube in, put the patch graft on then put the conjunctiva down with a superficial or episcleral dissection. This actually works quite well.”

• If the patient has a failed trabeculectomy at 12 o’clock or a little bit temporal to that, consider putting the tube through the existing scleral flap. “In this situation the globe has a tunnel in the sclera underneath the previous scleral flap and an existing peripheral iridectomy,” Dr. Francis points out. “That allows you to enter the anterior chamber more posteriorly, away from the cornea. If you’re able to enter more posteriorly, at the level of the iris, you’re not going to hit the iris because there’s an iridectomy there. You can simply put the tube through the iridectomy.”

• Use an inked needle tip to mark your tube entry location. “I always mark the tip of the 23-ga. needle with a surgical skin marker,” says Dr. Blieden. “When it enters the sclera it leaves a little ink mark, so you know exactly where your scleral entry site is when you go to insert the tube shunt. Sometimes I’ll do that while leaving the needle on a syringe of viscoelastic or BSS, in case I also need to re-inflate the chamber to help place the tube.”

• Use a guide wire to make it easy to insert the tube. Dr. Blieden says she came up with this strategy in the OR one day when she was having a particularly difficult time getting the tube into the correct position in the sulcus. “Sometimes it’s very challenging to reposition an existing tube, or even get a primary tube to go where you want it to, whether it’s above or below the iris,” she explains. “Using this strategy makes it easy to get the tube where you want it.

“First, use a side-port blade, or the 23-gauge needle you’ve used to create the tube track, to make a small corneal paracentesis across from where you’re trying to do your tube entry,” she says. “If necessary, you can inflate the anterior chamber with viscoelastic. Then, take a piece of 3-0 or 4-0 prolene suture and insert it through that paracentesis.

“Next, insert a pair of disposable 27- or 25-gauge Maxgrip retina forceps through the track that you’ve created for the tube,” she continues. “This is much easier than getting the tube itself into the correct track. Once the forceps is in the anterior chamber (or sulcus), use it to grab the prolene you inserted across the eye and pull it out through the planned tube track. The prolene suture then becomes a guide wire.

“Thread the tube over the prolene and then gently push the tube into the correct position, following the guide wire,” she concludes. “Once the tube is inserted, you can pull the prolene out through the paracentesis and remove the viscoelastic, if appropriate. This has quickly become my favorite way to move a tube into the sulcus, or reposition a tube in the eye.”

|

Intraoperative Tips

Other strategies for success include:

• When a patient is at high risk of hypotony, consider doing a staged tube procedure. Doing a staged tube means putting in the plate and waiting for the capsule to encapsulate before inserting the tube,” explains Dr. Francis. “Six weeks to two months later, you put the tube in the eye.” He points out that it’s good to try to identify patients at higher risk of hypotony ahead of time. “Patients at the greatest risk of hypotony are generally older,” he notes. “They’re vasculopaths with vascular disease and brittle blood vessels. With these patients, a staged procedure may be safest.

“Alternatively,” he adds, “you can insert the tube and tie it closed, and then bring the patient back at five weeks and open the ligature in the clinic using laser suture lysis.”

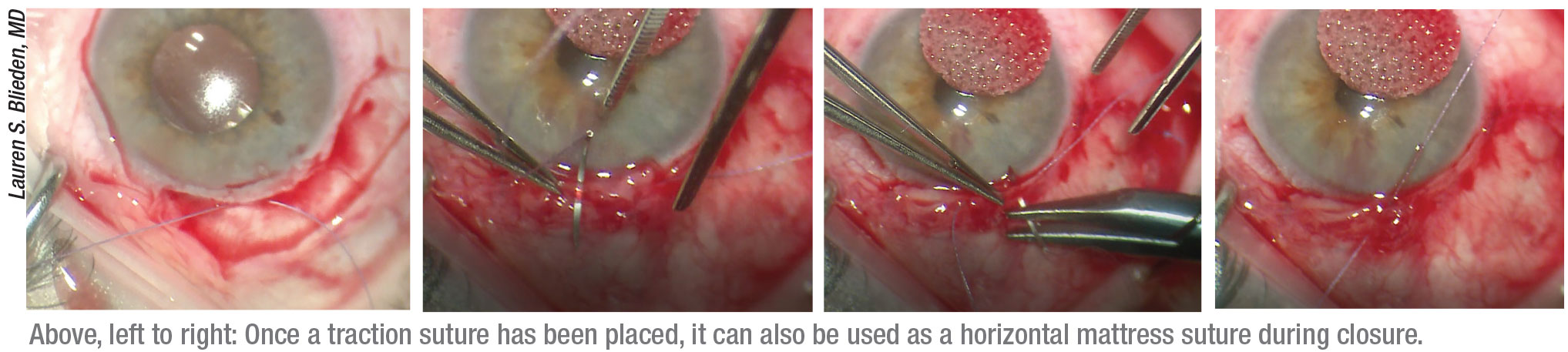

• Place your traction suture strategically. Dr. Blieden says she uses her 7-0 vicryl suture for corneal traction, but places it in the far peripheral cornea, aligned with the center of the limbal peritomy. “Doing this allows me to convert the traction suture into a horizontal mattress suture to close the central part of the incision at the end of the case,” she explains. “Many surgeons use a corneal traction suture to get exposure for the tube shunt, but I place it very peripheral—almost into the sclera. Sometimes, if the cornea is tenuous because of existing pathology or a transplant, it’s easier to first open the limbal peritomy until you get to bare sclera, and then place the traction suture at the corneoscleral juncture. That way, if the patient has had a corneal transplant or other corneal issue, you’re not insulting the cornea more.

“Next, I put the traction suture on a locking needle holder,” she continues. “I use a temporal Lieberman speculum because it has posts, so I can hook the suture around the posts. With the weight of the locking needle holder, that does a great job of holding the globe in place and allows me to manipulate the globe as needed. Then, when it’s time to finish up, I convert it into a horizontal mattress suture to close the center part of the peritomy.” (See example, p. 40.)

“I always use a traction suture placed at the limbus, in the quadrant in which I’m placing the implant,” says Dr. Gedde. “That’s very useful for rotating the eye to improve surgical exposure during the procedure. Then, I use that same traction suture at the end of the operation in the conjunctival closure.”

• If the tissue is fragile and falling apart, start the closure posteriorly, toward the muscle insertion. “This is a strategy I learned from Dr. Gedde,” explains Dr. Blieden. “When it’s time to close a relaxing incision, if the anterior tissue near the limbus isn’t healthy or substantial, start the closure posteriorly towards the muscle insertion, not at the limbus. This works because as you walk the tissue forward, you always end up with more tissue at the end of the closure.”

• Monitor carefully for postop complications. “These include complications such as erosion of the tube, double vision, corneal edema, choroidal effusion and shallowing of the anterior chamber,” says Dr. Gedde. “You need to be vigilant about monitoring for these complications. If they develop, early recognition is important so that appropriate treatment can be started.”

Controlling Pressure Pre-opening

When implanting a non-valved device, most surgeons tie a vicryl suture around the tube to close it for several weeks while the healing response causes a capsule to form around the plate. By the time the suture releases, the capsule has formed and acts as a flow restrictor.

Since this process takes several weeks, a key decision for the surgeon is how to control the pressure during the time it takes for the capsule to form and the vicryl suture to open up. Some surgeons put fenestrations in the tube to allow a small amount of flow; others may choose to do another procedure at the same time, such as endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation or an angle-based MIGS procedure. Some create a ripcord suture that will allow them to open the tube at a time of their choosing.

Surgeons offer these suggestions:

• Do a MIGS procedure at the same time. “If I’m putting in a non-valved implant, and I need to get the pressure down in the short term, I’ll consider doing a MIGS procedure at the same time,” says Dr. Francis. “Usually it’s a goniotomy, because you’re generally not putting in MIGS implants unless you’re doing cataract surgery. Doing this at the same time may help control the pressure for the first six weeks.”

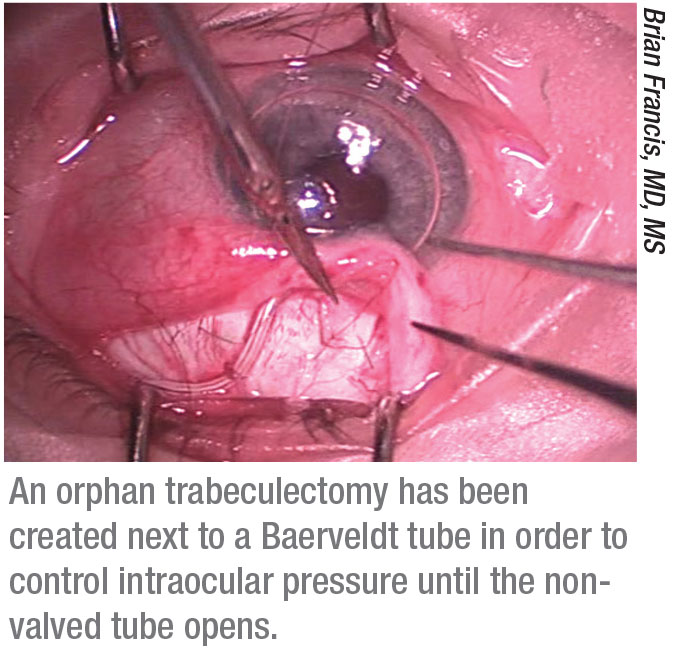

• Consider creating an “orphan trabeculectomy.” “If the patient doesn’t have an existing trabeculectomy,” says Dr. Francis, “you can make a new one next to the tube without using mitomycin-C, with the expectation that it will fail. By the time it fails the tube will be open and functional, and you will have managed the pressure during the interim.”

• If the patient already has a failed trabeculectomy, reopen part of the trabeculectomy flap without using mitomycin-C. “Doing this will bring the pressure down,” explains Dr. Francis. “Over time, that flap will scar down again because you didn’t use mitomycin, but by then the tube will be open. I call that an ‘orphan trabeculectomy revision.’ It’s a nice option, because the flap already exists.

“Reopening it is similar to a needling procedure,” he adds. “I generally use an MVR or side-port blade to tunnel under the flap and open it again. However, you have to be careful not to open up the entire flap, because you’ll get too much outflow and cause hypotony. I generally try to open up just half of the flap and then check the flow.”

• Don’t wait to adjust the patient’s glaucoma medications. Dr. Francis suggests tapering the patient’s glaucoma medications postop. “If the tube suddenly opens up, the eye may become hypotonous,” he says. “At the very least, you don’t want the patient to be on maximum aqueous suppressants during that time. If that happens, most eyes will recover, but some eyes won’t; the result can be a flat chamber, choroidal hemorrhages and choroidal effusions.”

Dr. Gedde notes that some recent evidence suggests that adding medical therapy earlier may reduce the chance of a hypertensive phase, which is common after tube shunt surgery.1 “Treating that with medical therapy may reduce the magnitude and duration of the hypertensive phase and improve long-term pressure control,” he says.

Dr. Blieden agrees that when implanting the Ahmed FP7, early aqueous suppression can help to blunt the hypertensive phase. “A hypertensive phase is fairly common with these implants,” she says. “So, as soon as the patient gets to double-digit pressure I’ll add in a little bit of an aqueous suppressant. I’ve had a lot of success with this approach.”

Opening the Tube Yourself

|

In some cases, surgeons prefer to control when the tube opens, with the obvious advantage that any unwanted effects are more easily monitored.

Dr. Gedde notes that if you choose to open a nonvalved tube yourself, you should wait at least one month. “When I’m placing a nonvalved implant, I use 7-0 vicryl to temporarily restrict flow through the device,” he says. “That suture reliably dissolves five or six weeks after surgery, which is enough time to allow a capsule to form around the endplate. But if you prefer to control the time of tube opening, you can use a laser to lyse the suture. If you do, wait at least one month to make sure the capsule has fully formed around the endplate.”

When a uveitic glaucoma patient receives a nonvalved shunt, Dr. Blieden suggests leaving a permanent ripcord in place for as long as possible. “Uveitic patient outcomes are very unpredictable,” she notes. “After I implant a Baerveldt or ClearPath 250, I tie off the tube around a 3-0 prolene ripcord and leave it there for as long as humanly possible.

“Some of these patients are impossible to control with medications, but after I put in the tube—still tied shut—their pressure normalizes,” she continues. “In some cases, four years after the surgery I still haven’t needed to open the ripcord. I can’t explain this, but it scares me to think that if I’d put in a valved tube, or a nonvalved tube without the ripcord, I would have been dealing with severe hypotony. So, I like to have the control of a ripcord in my uveitic patients. I typically advise doctors to resist the impulse to open it early. Wait it out. I won’t open a uveitic tube before eight weeks, even if the pressure is in the 30s.

“With these patients, some surgeons might choose to do a staged Baerveldt implantation, where you have to go in and reopen that quadrant of the conjunctiva,” she notes. “However, with this ripcord approach you can just cut down and pull the ripcord. You can do a scleral cutdown at the same time, if you need to.

“I use the same approach with my very old patients,” she adds. “If I’m worried about the patient, I want to make sure I’m controlling how and when the tube opens.”

If a Primary Shunt Fails

If a tube shunt has already been implanted but the pressure-lowering that results is insufficient, the surgeon will have to decide what to do next.

One option is to add a second shunt. Dr. Francis says that if he decides to do this, in most patients, he’ll put the second tube in the inferonasal quadrant. “However, if the patient is monocular I’d place it in the superior nasal quadrant,” he says.

Of course, adding a second shunt means placing additional hardware on the eye, so most surgeons are careful to consider other options first. Those options include:

• Try cyclophotocoagulation. “Typically, if a patient has an Ahmed FP7 valve, which is a small implant, instead of adding a second shunt I’ll try cyclophotocoagulation first, whether it’s a micropulse or ECP,” says Dr. Francis. “However, you have to avoid creating hypotony, which could happen if both the tube and your aqueous reduction procedure work well. Don’t be overly aggressive with the cyclophotocoagulation.”

Dr. Blieden says that in most cases she opts to perform an adjunctive cyclodestructive procedure instead of placing another shunt. “I may add a second shunt if the patient is young and phakic,” she says, “but most of the time, if the first shunt fails, I opt for

doing secondary cyclophotocoagulation.”

• If the primary tube is valved, try replacing it with a nonvalved tube. “If a small amount of cyclophotocoagulation fails to get us to the desired target with an Ahmed FP7,” says Dr. Francis, “I’ll take the Ahmed out and put in a nonvalved Baerveldt or Ahmed ClearPath, because I think those work better in the long term. That avoids the need for another tube in another quadrant. If the patient already has a nonvalved Baerveldt, Molteno or ClearPath, then I’ll go ahead and try micropulse or ECP. If that fails, then I’ll put in a second tube.”

Dr. Francis points out that switching the tube can also work in the opposite situation. “If the patient has a Baerveldt and the pressure’s too low, which we sometimes see in uveitic glaucoma or neovascular glaucoma, you can take out the Baerveldt and put in an Ahmed FP7,” he says. “That generally will prevent hypotony while still controlling the pressure.”

Dr. Blieden says she’ll only consider switching out a shunt if the current one has become a major problem. “I’ll only resort to that if the shunt has eroded, or the patient is hypotonous,” she explains. “If it’s just an issue with controlling the pressure, I leave it alone and use other options to control the pressure.”

• Try to revise the primary shunt capsule. “Some surgeons suggest revising the original shunt—for example, excising the capsule around the endplate in hopes that when the new one forms it will be thinner,” notes Dr. Gedde. “However, in my experience, if the patient formed a thick capsule to begin with, it’s unlikely the new one will be different. I generally leave the original shunt alone, as long as it’s not obstructed. In my experience, if it’s working but not lowering pressure adequately, the best options are putting another shunt in a different quadrant or doing cyclophotocoagulation.”

Dr. Gedde adds that it isn’t yet clear what the preferred surgical approach should be when a tube shunt fails. He’s an investigator in the American Glaucoma Society’s Second Aqueous Shunt Implant Versus Transscleral Cyclophotocoagulation Study (ASSISTS), a multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing cyclophotocoagulation and second tube shunt placement after primary tube shunt failure. “Hopefully, this trial will provide information to guide surgical decision making in the future,” he says. REVIEW

Drs. Gedde and Blieden report no relevant financial ties to any product mentioned. Dr. Francis is a consultant for New World Medical, Endo Optiks and Iridex.

1. Pakravan M, Rad SS, et al. Effect of early treatment with aqueous suppressants on Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation outcomes. Ophthalmology 2014;121:9:1693-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.03.014. Epub 2014 May 10.

2. Costa VP, Azuara-Blanco A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive mitomycin C during Ahmed Glaucoma Valve implantation: A pros-pective randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology 2004;111:6:1071-6.

3. Cantor L, Burgoyne J, et al. The effect of mitomycin C on Molteno implant surgery: A 1-year randomized, masked, prospective study. J Glaucoma 1998;7:4:240-6.