Glaucoma surgery is an essential tool in a glaucoma specialist’s armamentarium. But sometimes—even when an outcome appears to be good and vision measures close to 20/20—patients complain that their vision isn’t right. In many cases the complaint is triggered by fluctuating vision.

A number of issues can cause this type of complaint, including hypotony, refractive error, astigmatism from the sutures and surgery, a slow, chronic bleb leak, corneal folds, macular striae and inflammation. Here, I’ll discuss the different problems that may be causing these vision issues, and offer some suggestions for managing them and making sure your patient ends up happy.

Refractive Changes

Sometimes what’s disturbing the patient is a refractive alteration, such as a myopic shift or an increase in astigmatism. Sometimes—though not always—these changes are related to postoperative hypotony, which may occasionally happen despite our best efforts

• Myopic shift. One of the consequences of hypotony can be a myopic shift in the patient’s refraction. The loss of intraocular pressure causes the anterior chamber to shallow, and the whole lens-iris diaphragm moves forward, leading to the myopic shift.

• Astigmatism. New postop astigmatism can cause your patient to perceive that “something is off” about their vision. Astigmatism can result from a number of possible causes:

—Hypotony. Hypotony alters the dimension of the eye; one of the consequences can be astigmatism.

—Cautery. If you’re doing a tube or trab, you may find that you need to control a bit of bleeding, and you can use cautery to close off some of the leaking blood vessels. It’s not uncommon for surgeons to do this along the limbus. Light cautery usually doesn’t produce any unintended side effects, but if you have to do more heavy-handed cautery you can burn the collagen on the sclera, which can cause the tissue to shrink and pull on the anterior part of the eye. That can remodel the tissue, changing the shape of the sclera and causing astigmatism.

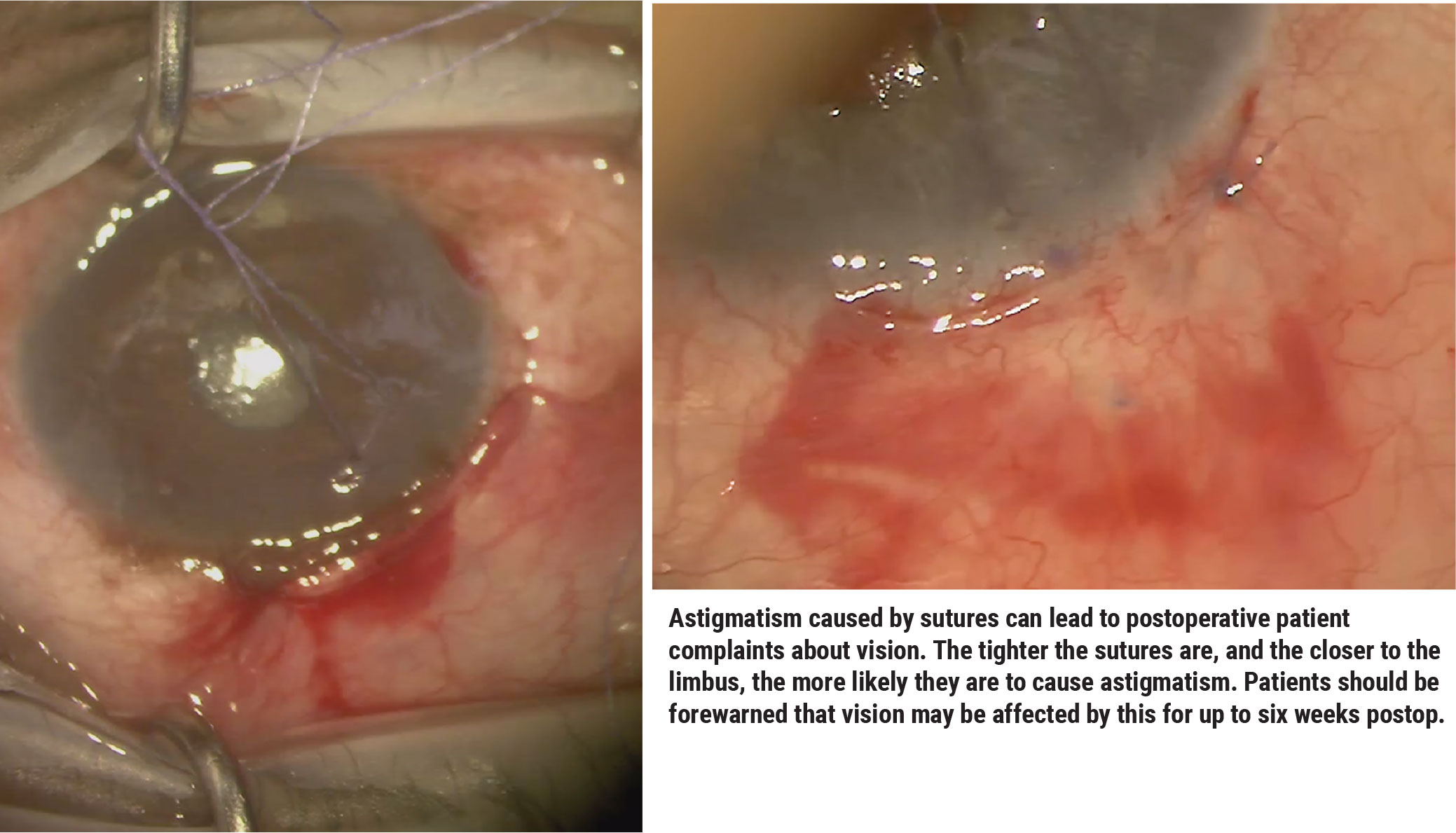

—Sutures. Intraoperatively you may place vicryl sutures that will dissolve, and the sutures can lead to temporary vision changes. The tighter the sutures are, and the closer to the limbus or cornea they are, the more likely they are to cause astigmatism. The key is to tell patients before any major glaucoma surgery that their vision can be affected for up to six weeks after surgery. That’s how long the sutures will take to dissolve.

Postop, you can remove the sutures if there’s good closure and no leaks. However, I’d wait three months before doing any permanent refractive correction.

Chronic Bleb Leak

Another possible explanation for post-trabeculectomy patients with 20/20 vision but a visual complaint is a bleb leak. Symptoms may include: decreased IOP; occasional tearing; occasional blurry vision; shifting vision quality; and/or the patient says that pressing on the eye causes a change in vision. Those are indications that you should do a fluorescein stain to check for a bleb leak.

|

If I find a bleb leak early in the postop period, I may reduce the patient’s steroids to increase the rate of healing. (This is somewhat controversial; every surgeon has a different idea about the best way to address this.) Usually when I cut back on the steroid I see the patient back in a few weeks and the bleb leak is gone. Of course, it’s necessary to continue topical antibiotic coverage until the leak has stopped.

Occasionally a bleb leak is caused by the eyelid rubbing against the bleb; in that situation I’ll put on a bandage contact lens to keep the lid from touching the eye. I’ve used pressure patches in the past; you roll up a patch and press it down on the eye so that the eyelid is stuck down and isn’t rubbing against the wound. That has variable success.

When dealing with a bleb leak late in the game—three to six months postop or more—my advice would be to revise the bleb, because at that point it’s not going to heal on its own. A bleb leak at this point usually means the bleb is cystic, or has a problem that’s not wound-related. I take these patients back into the OR and revise the bleb. (Some surgeons attempt autologous blood injection, compression sutures, aqueous suppression and other techniques prior to bleb revision.)

Most times, when we revise a cystic bleb we cut into the bleb, remove the cystic tissue and then pull down healthy conjunctiva and suture it up. However, that doesn’t always work; there’s scarring all around the original bleb, and sometimes you simply can’t pull the tissue down as far as you want.

One alternative, minimally invasive approach I’ve encountered was developed by Dr. Neeru Gupta, MD, at the University of Toronto.1 She’ll sometimes rotate the eye downward to expose the superior bleb; then she injects an anesthetic behind the bleb, causing the conjunctiva to balloon up to the outer edge. She then grasps the raised conjunctival tissue with 0.12 forceps and brings it down, using a 10-0 nylon suture to anchor the leading edge of the tissue to the limbus. This effectively covers the leaky area with healthy tissue.

Corneal Folds

Variability in vision can also be caused by folds in the corneal epithelium, another possible side effect of hypotony. If hypotony is present I always look for corneal folds, because hypotony can cause the cornea to contract. The resulting folds can be very subtle, but they can cause problems with the patient’s vision over the long term. Placing fluorescein into the eye will reveal the edges of the folds.

The treatment for this problem is to first of all determine what the cause of the hypotony is. Is it overfiltration? A leak? If necessary, revise the bleb. I also look into any glaucoma drops the patient may be using. I’ve seen many patients continue their drops postoperatively, even if their pressure is low; you have to get them to stop using any potentially IOP-lowering drops. If I know the patient is a steroid responder, I may also add a steroid to increase the IOP.

Hypotony Maculopathy

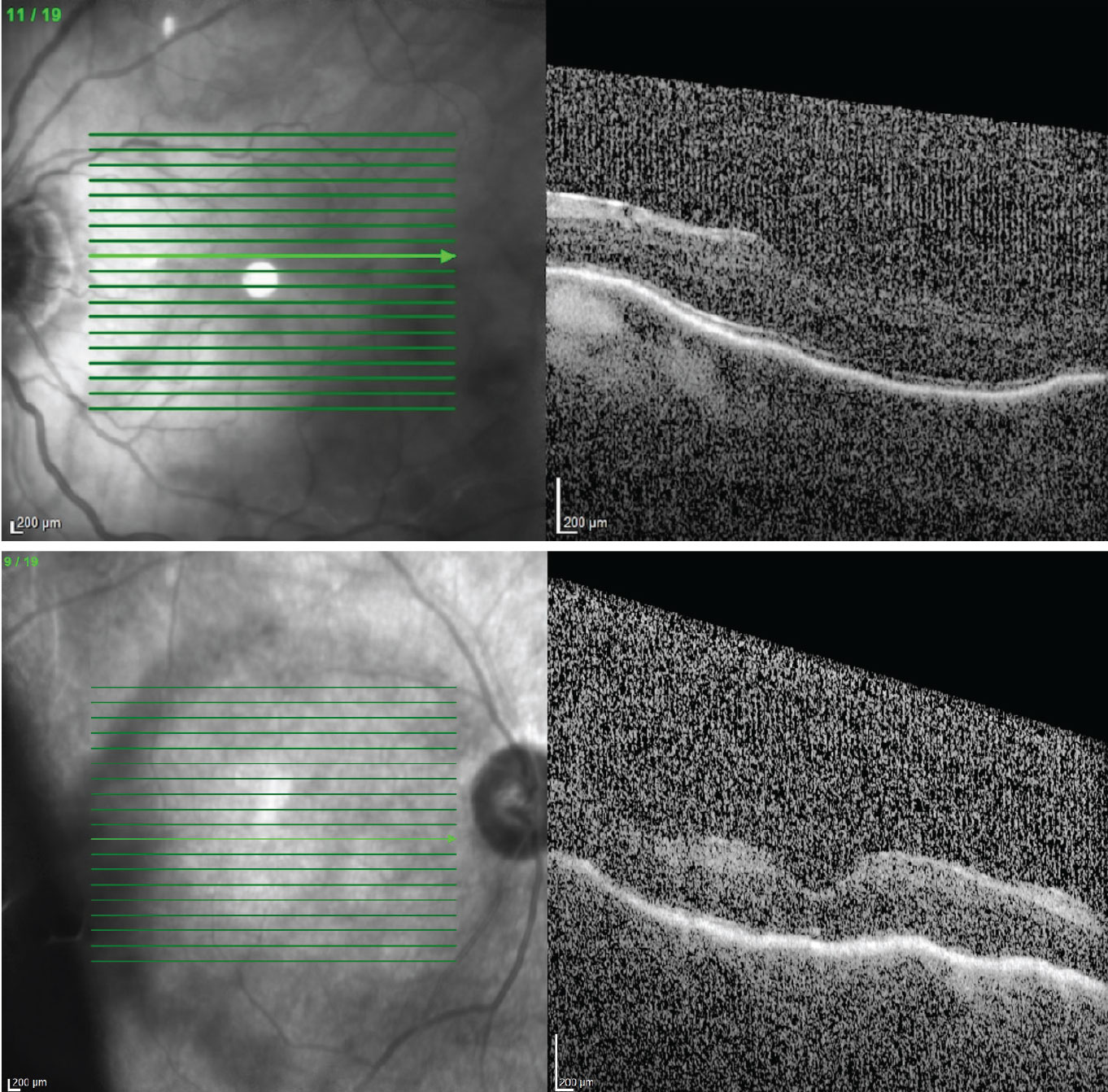

Variable vision can also be caused by hypotony maculopathy. For this reason, if a patient comes in and her vision isn’t quite where I want it to be, I get a macular OCT and look for striae. Usually this problem is symptomatic, meaning that the patient isn’t 20/20. However, I’ve been surprised that some patients with pretty good vision—20/30 or 20/25—turn out to have a touch of hypotony maculopathy. So it’s important to assess the condition of the macula. (Risk factors for hypotony maculopathy include young age, primary filtering surgery and myopia.)

I always recommend a macular OCT for postop patients with blurry vision. If I find hypotony maculopathy, I do the same thing as if I find corneal folds: I make sure the patient isn’t using any glaucoma drops, and I look at the bleb to make sure it’s not overfiltering or leaking.

Sometimes, there’s not much you can do in this situation. If the posterior pole is involved and vision is affected, you can surgically close the trabeculectomy or tube. However, if the patient is still 20/20, you may just want to watch and wait. (Usually, if a patient is 20/20, most surgeons won’t choose to go in for another surgery.)

|

|

If a patient complains of blurry vision postop it's a good idea to get a macular OCT, as hypotony maculopathy may be causing macular striae. If found, make sure the patient isn't still using preop glaucoma drops, and check the bleb for overfiltering and/or leaking. Top: Macular striae has caused vision to drop to 20/80. Bottom: Vision in this eye is 20/200. |

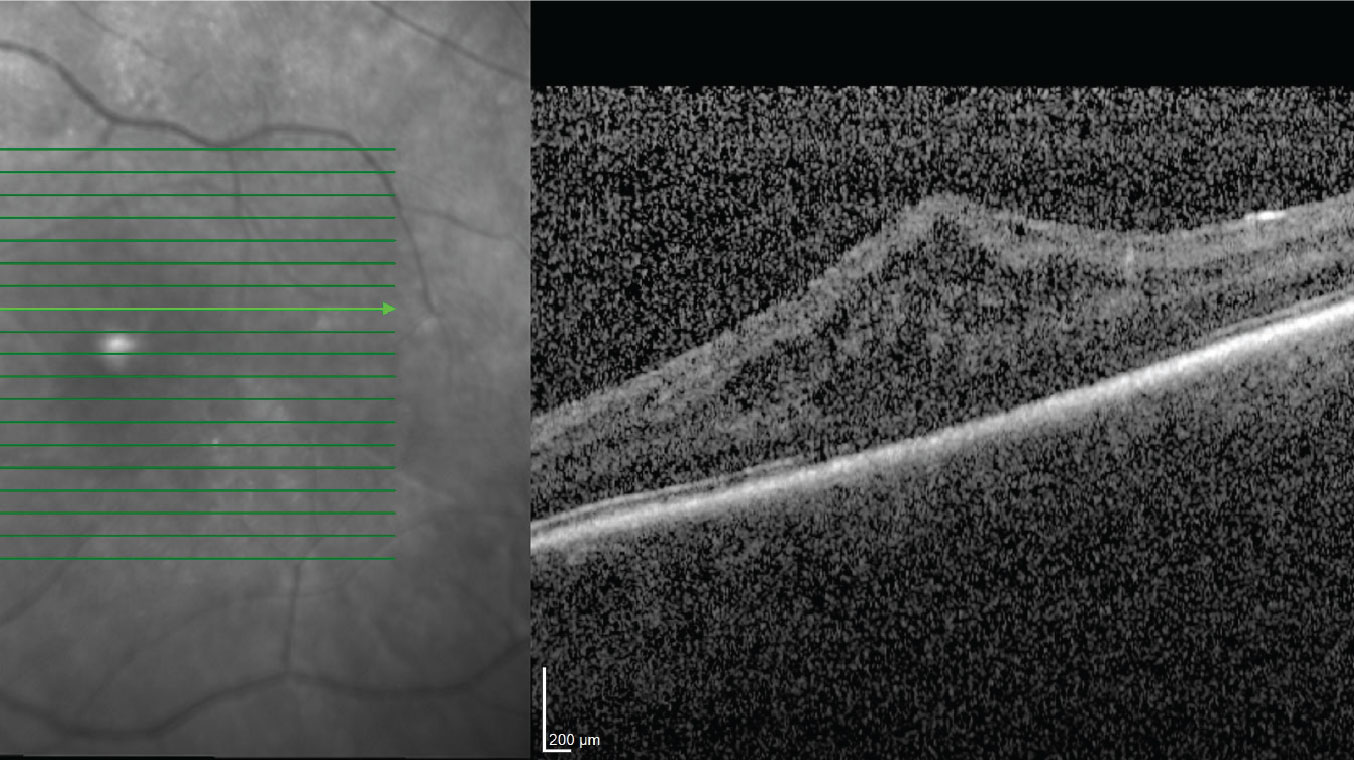

Inflammation

Hypotony and inflammation are often intertwined, and ironically, either one can trigger the other. For example, mild inflammation—which can happen after almost any surgery—can cause the inflamed tissue to shut down its activity until the inflammation resolves. Intraocular inflammation often affects the ciliary body, and that can lead to decreased aqueous production and hypotony, resulting in blurriness and pain.

However, the reverse is also true: hypotony can lead to inflammation. A patient might have hypotony as a result of a valveless tube implant opening; all of a sudden, the pressure decreases. The eye notices the change and for reasons we don’t entirely understand, it becomes inflamed. This can lead to macular edema, cell and flare in the anterior chamber, and ultimately a change in vision.

In most cases these issues will resolve on their own, but if they don’t, my treatment would be to increase the topical steroids and start topical NSAIDs.

|

|

Inflammation can lead to hypotony (and vice versa). Inflammation inside the eye can cause ciliary body shutdown and decreased aqueous production, resulting in very low pressure. |

Getting Back on Track

As valuable as glaucoma surgery is, it can lead to postop issues, including refractive changes, astigmatism, induced myopia and variable vision. If your patient has low IOP and variability in vision, you need to determine the cause. Check for corneal folds and bleb leaks, and look at the macula; usually one of these will have an answer for you. Also, keep in mind that although we usually avoid surgery when the in-clinic vision measurement is close to 20/20, some causes of variable vision—such as bleb leaks or overfiltration—may require further surgical intervention.

Dr. Bedrood is a glaucoma specialist practicing with the Acuity Eye Group in Pasadena. She reports no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Gupta N. Incision-free minimally invasive conjunctival surgery (MICS) for late-onset bleb leaks after trabeculectomy (an American ophthalmological society thesis). Am J Ophthalmol 2019;207:333-342.