As part of the Department of Oph thalmology at the University of California Davis, I made the transition to EHR in 2007. Here, I’d like to share some of my experiences with EHR from the perspective of a glaucoma specialist, and offer a few suggestions for others in similar situations who are considering making the switch.

The Impact of EHR

In 2006 the American Academy of Ophthalmology did a survey to find out what concerns ophthalmologists had about switching to EHR. The three main things doctors were worried about were: 1) the financial impact of making the switch; 2) the impact on productivity; and 3) how it would affect their ability to create drawings for an eye exam—a concern of particular interest to glaucoma doctors.

At UC Davis, we decided to track our financial and productivity information during and after the transition to EHR to see what actually happened.

At UC Davis, we decided to track our financial and productivity information during and after the transition to EHR to see what actually happened. Some of the results were a little surprising. The year we went live, we thought our overall revenues would dip. That turned out not to be the case; our revenues increased from the time we went live. (See chart, p. 64.)

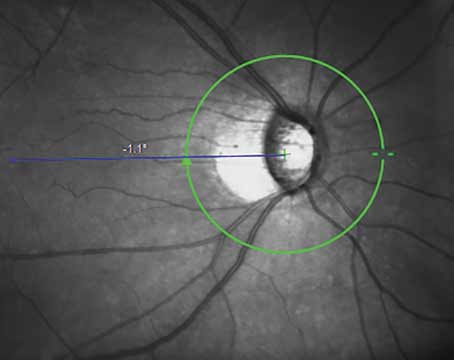

To investigate the impact of EHR adoption on our productivity, we looked at both imaging volume and patient volume. Our imaging workflow changed when we became paperless; instead of printed images placed into the patient’s chart, images were captured digitally, stored on a server, and could be viewed from anywhere via an Internet browser. We could easily show patients who were sitting in the exam room images of their optic nerves or their visual fields; often this neatly illustrated what was happening with their disease process.

Our data showed that the volume of images we were ordering jumped after EHR was implemented. I believe this happened for two reasons:First, the images are so readily available and easy to pull up on a computer that people are motivated to order more. Second, because drawing is more of a challenge with EHR, we use photos for documentation more frequently.

In terms of patient volume, the overall number of patients seen per provider increased. Despite this, my personal experience was that I saw slightly fewer patients per day than before. I think this may be the result of different personal styles and ways of using the EHR system.

The Drawing Dilemma

An ophthalmologic exam is usually very picture-driven, and most of us who trained in the era of paper are accustomed to drawing everything we see in the eye. So, at UC Davis we wanted to find out how often our doctors were drawing once we converted to EHR.

At least in our institution, the rate of drawing dropped significantly. I suspect the reason is that the existing drawing programs in most EHR systems are very clunky—a technological limitation that really needs to be addressed. (Drawing tablets can be used, although using them is similar to drawing with a mouse, due to limitations inherent in the EHR drawing software.)

In fact, when surveyed about what they liked and disliked about EHR, most of our respondents were very dissatisfied with the drawing program. As a result, our exam documentation became image- and text-driven rather than pictorial. This is indeed a shift in our mental concept of the eye exam.

As it turns out, describing exam findings in images and words can work well, and our quality of care remains very high. The one caveat is that an exam may take more time; if I had better drawing tools, I think I’d get through them much faster. It’s a trade-off: The verbal description tends to be more complete than a scribbled drawing—in fact, I think the depth of the description in the exam note might actually suffer if we return to drawing—but it slows you down a little.

EHR Advantages

As a glaucoma specialist, I see pros and cons to EHR. The most serious negative (at least for now) is the lack of an easy-to-use drawing program and the fact that it takes more time to document an exam. However, there are quite a few positives to balance out that shortcoming:

- You see visual fields and images right away. There’s no waiting for processing or printing.

- Data is easy to retrieve. Perhaps the greatest benefit of EHR for any physician is having data all in one place and easy to access from any location. Ten years ago our department wasn’t digital; our cameras were film-based. Optic nerve images were printed out as slides and stored in folders downstairs in a basement room. If I was examining a patient on the fly and wanted to see the patient’s optic nerve photos, I’d have to send my technician down to the basement to find the file and bring the images up. Half the time the technician couldn’t even find what I needed because something was misfiled or lost or moved. (Since switching to EHR, we have rarely lost data.)

- Readily available data helps your credibility. Suppose a patient makes a phone call to my office to request a medication change. When I see the patient for an appointment, the electronic record tells me that this happened, before I start talking to him. I think it boosts your credibility as a physician to have this kind of information in hand when you see the patient. (Conversely, if the patient walks in and you forget some major aspect of her concerns, it reduces the patient’s trust in you.)

- It’s a great patient education tool. Glaucoma is a very intangible disease; it’s hard to explain it to a patient. If you show a patient some-thing concrete like a series of visual fields or photos, she gets a much better sense of what’s happening. The patient can see how the optic nerve has changed, or how an area of visual field loss has enlarged. Among other things, this probably helps to encourage patient adherence with medication use.

- Care is coordinated between doctors. The increased ease and speed of communication between physicians benefits our patients and saves us time and effort. (When I’m a patient myself, I want my care to be well-coordinated; so given the choice, I’d choose to be part of a system that has an EHR.)

- It improves communication between doctors and staff. Our survey found that doctors really liked the ability to easily message staff members. For example, patients make requests all the time. It’s very easy for me to message my technician or the administrative assistant and say, “The patient wants to have the surgery scheduled on such-and-such a date.” It’s much easier than hunting the person down to have a conversation.

- E-prescribing. This aspect of electronic medicine received high marks in our satisfaction survey. It also created a “wow factor” with the patients. They kept asking me, “You mean the prescription is already at my pharmacy?”

- Patients can access their own medical records. Our system lets pa tients access their own medical records at home online, which was one of the goals for improved health care in the United States listed by the Department of Health and Human Services back in 2004.

- It provides new ways to increase patient adherence. EHR can potentially help us increase patient adherence in several ways. Our system is implementing a function that will allow us to see when patients filled their prescriptions. Patients may say they take their medication every day, but if you look at their EHR record and see they’ve only had three refills in six months, you know they’re not using the medication as prescribed. So this may help us counsel patients appropriately regarding their medication use.

Another way to increase adherence would be to have reminder messages automatically go to patients—either when they log in to see their medical records, or on a regular basis, sent to an email address or handheld device. At this year’s meeting of the American Glaucoma Society, Michael V. Boland, MD, reported a study in which sub jects determined to be poorly adherent to their medications received automated reminders via text or voice message. (A control group of similar subjects didn’t receive any messages.) Those receiving the messages improved from approximately 50 per cent compliance to 67 percent compliance, while the control group didn’t improve at all (p=0.002).

In addition, interesting facts about glaucoma can be sent to patients on a regular basis using similar means. Research suggests that the more patients know about their disease and the more engaged they are, the more likely they are to take their medications.

- It minimizes the need for transcription services. One important change wrought by EHR is that we dictate much less. In the past we’d dictate operative notes and send them to a transcription service. Now, when we do a procedure or a surgery we have an on-screen template we’ve created that we modify so that it describes what happened during a particular procedure. Because transcription services are expensive, this has become an area of major financial savings. I believe our transcriptions have been reduced by 90 percent here at UC Davis; one study showed that another institution saved $300,000 in a year by not doing as much transcription.1

Manipulating Data

In addition to these advantages, because the system is computer-based, it also allows you to manipulate and clarify data in ways that would be impractical without digital help:

- You can graph data over time. For example, you can create a chart showing IOP at each visit vs. medications taken or surgeries performed. The retina people in our group are developing a flow sheet that graphs changes in OCT-measured retinal thickness as they perform injections.

- New ways to compare images. Recent studies are suggesting that the concept of “flickering” images (i.e., moving back and forth between precisely aligned past and current photos or scans) has the potential to improve diagnosis as well. (For example, see Smith SD, et al. IOVS 2011;52:ARVO E-abstract 4168.) Obviously, this is something computers are well-suited to do, and it could turn out to be a valuable aid in glaucoma diagnosis.

In the meantime, we use a program that allows us to pull up photos from different dates and show them side-by-side on the computer screen, which is quite helpful.

- Inevitable future technological advances. While paper charts have probably advanced as far as they’re likely to advance, computer technology is in its infancy, and it’s becoming faster and more powerful every year. Being on EHR will allow us to take advantage of new ways of capturing, consolidating, displaying and interpreting information as they appear.

Pearls: Making EHR Work

Pearls: Making EHR Work

If you see a great many glaucoma patients and you’re thinking of moving to EHR, I’d offer the following suggestions, based on my experience here at UC Davis:

- Consider not loading old records and images into the system. We considered pulling all of the visual fields from everyone’s chart and scanning them in, but the mountain of information was so huge that it wasn’t practical. Instead, we opted to have the paper charts on hand for as long as necessary.

That turned out to be workable, and eventually we stopped asking for the paper charts. Part of this was simply getting used to not relying on them; part of it was that our need to see previous visual fields only went back so far. Of course, now that we’re past that point and only using the EHR system, sometimes a question will arise and we’ll have to order the paper chart to look at the data. However, that doesn’t happen very often.

- Begin by using the image-storing part of the system first. We went live with an electronic system that stores all of our images three years before the rest of the system was activated. (During that period we used the paper charts but also called up the recent digital images as needed.) As a result, we had three years of imaging data in the system, including visual fields, when we went live on the full system. This helped to shorten the period of time during which we needed to have paper charts handy to reference earlier data.

Of course, we did all this before the era of “meaningful use” and government incentives. A practice making the switch at this time might not feel comfortable allowing three years to get the jump on image-storing before going live.

- Install the largest computer screens possible in your examination and charting rooms. The larger screens will make reviewing visual fields and OCT results much easier. On some of our smaller screens, we can’t read OCT data printouts when comparing two different time points. We currently use 22-in. screens, but we wish we had gone larger.

- Customize your template. Make sure your template features pertinent information like pachymetry, max-imum IOP, target pressure, glaucoma procedures performed and so forth, all in one place.

- During exams, keep your focus on the patient. One thing that patients do complain about with EHR is that physicians can get drawn into typing into the computer, which may require you to turn away from the patient to type. Patients don’t like it when you become engrossed in typing or looking up their information and stop talking to them.

To prevent this from becoming an issue, it’s important to be conscious of this and make an effort to look the patient in the eye. When the patient is asking you a question, stop typing, turn around and face him and engage him as you answer the question. (If you have the opportunity, try to mount your computer screen in the exam room so that you’re facing the patient when looking at the screen.)

- Allow your staff time to get familiar with the system. Our transition to EHR went very smoothly, and I think part of the reason was that the EHR was long in coming. We had access to the EHR system in a “look-up” function several years before it was implemented, so we could call up lab reports, patient information, and so forth. When we went live we already had some idea of what we were getting into.

- If you’re a small practice, consider partnering with a hospital or medical group. This is potentially a way to mitigate the cost of an EHR system. A medical group or hospital that already has an EHR system may be willing to provide it to you either free or at a reduced cost in exchange for getting patient referrals. It benefits a medical group to keep all the doctors tied together on a common system, and hospitals benefit by encouraging physicians to either operate at their facility or admit patients there.

- Make sure you have at least one physician champion. These individuals will stay on top of the details and help the rest of the group transition.

- Have your physician champion(s) train first. Our computer technical staff initially created training workshops for all the doctors going live in the UC Davis system. We discovered that the trainers had a glut of knowledge about the EHR system, but almost zero knowledge about the flow of an ophthalmology office or what was involved in managing a glaucoma patient. They weren’t talking about the right medications, and the clinical scenarios didn’t make sense.

So, another physician and I took their materials and personalized them, making them specific to ophthalmology and glaucoma so the people being trained would grasp what we were trying to show them. The workshops were far more effective once we modified them.

- Let your physician champions use the system before the rest of the practice. UC Davis gave me and another physician early access to the EHR so that we could use the system while seeing patients before the major go-live date. This allowed us to see what worked and what didn’t work, and we were able to tweak the system, solving many problems before they affected the entire practice. (No amount of demonstration practice can replace actually using it yourself under real day-to-day conditions.)

Does EHR Benefit Glaucoma?

Does EHR Benefit Glaucoma?

Despite the transition data collected at UC Davis, it’s hard to draw any firm conclusions about how EHR will affect a given glaucoma specialist; we only represent a tiny fraction of the doctors included in the UC Davis transition data.

Nevertheless, I believe some basic conclusions can be drawn from our experience. When we conducted our post-EHR-transition satisfaction survey, we included some big-picture questions. One of them was: Do you think EHR has improved our patients’ quality of care? The overwhelming response was yes. The other big question was: Would you go back to using paper records if you had the chance? Ninety-seven percent of respondents said no.

What do I think of the new system, speaking as a glaucoma specialist? I think the quality of care is excellent. And I would definitely not go back to paper records.

Dr. Lim is associate professor of ophthalmology and vice chair and medical director of the UC Davis Health System Eye Center in Sacramento.

1. Barlow S, Johnson J, Steck J. The economic effect of im-plementing an EMR in an outpatient clinical setting. J Healthcare Information Management 2004;18:1:46-51.