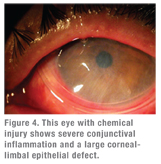

An ocular chemical burn can come from a gas, liquid or solid; an alkaline or acid base, organic and nonalkaline compound. Of course, anytime a chemical comes in contact with the ocular surface, the most urgent action is copious irrigation.

Management later in the course requires an understanding of the chemical compound that caused the injury and the cellular events occurring during each phase. A particulate nonliquid substance requires removal, much like a foreign body.

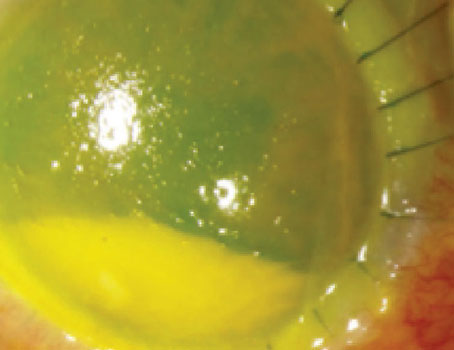

Management later in the course requires an understanding of the chemical compound that caused the injury and the cellular events occurring during each phase. A particulate nonliquid substance requires removal, much like a foreign body. Conventional treatment consists of supportive antibiotics, steroids and patching, but the effectiveness of this approach depends on a number of factors, However, amniotic membrane is the only treatment that has been shown to dramatically alter the course of an acute chemical burn thanks to the miraculous biological properties of the membrane and how it affects wound healing. Instead of letting adult wound healing take its course—that is, inflammation and scarring—fetal amniotic membrane regenerates tissue.

|

|

The first reports of treating corneal chemical burns with amniotic membrane surfaced about 10 years ago, and today it is accepted as standard practice. The Food and Drug Administration has approved two cryopreserved amniotic membrane-based products for treatment of acute chemical injury to the cornea.

How the amniotic membrane itself is prepared is important in determining its efficacy. The FDA regulates human cell, tissue, or cellular or tissue-based product (HCT/P) preparation of autologous tissues. However, not all amniotic tissues may claim to promote wound healing. The FDA issued a compliance action that only “minimally manipulated” cryopreserved amniotic membrane may claim to be for wound healing. The decellularized and dehydrated amniotic membrane cannot make such a claim without premarket approval because such a process removes “cytokine-containing cells from this tissue would interfere with human amniotic membrane’s ability to actively mediate wound repair and wound healing.”1 (Disclosure: I invented the cryopreservation technology for human amniotic membrane 17 years ago.)

|

|

- AmnioGraft (Bio-Tissue Inc., Miami), a cryopreserved amniotic membrane FDA-approved as HCT/P. The surgeon attaches this membrane with sutures. In the chemical burn setting, this may be cumbersome because it requires the transfer of a burn patient to an operating room for graft placement—and scheduling corneal surgery can be problematic when the patient may have many other injuries that are just as urgent.

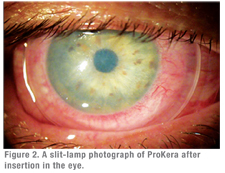

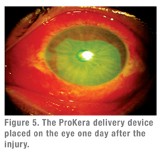

- ProKera (Bio-Tissue Inc.) is an FDA-approved, class II medical device that fastens AmnioGraft to a contact lens-like polycarbonate ring. ProKera was developed with support of a research grant from the National Institutes of Health. This self-retaining delivery mechanism obviates the need of using sutures, and hence allows cryopreserved amniotic membrane to be delivered in an office setting or in the emergency department without delay. Medicare this year has approved a new CPT code (65778) for reimbursement of ProKera placed in the office.

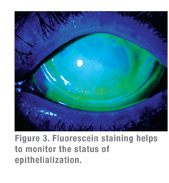

A number of encouraging results using amniotic membrane to treat acute ocular chemical burns have appeared in the literature. A 2000 report first investigated the use of amniotic membrane transplantation for moderate to severe acute chemical or thermal burns in 13 eyes—seven eyes with grade II or III burns, and six with grade IV. At an average follow-up of 8.7 months, 11 eyes showed epithelialization at two to five weeks, and only one eye had symblepharon. In the group with grade II or III burns, none had developed limbal cell deficiency, but all eyes with grade IV burns did experience limbal cell deficiency.2

In 2003, another report of using the aforementioned amniotic membrane patching (AMP) for an acute ocular chemical injury appeared based on a three-center study out of Japan and Miami. Of the five cases in this study, four were grade II epithelial defects, the fifth was grade III. All cases experienced rapid pain relief after AMP, epithelialization of the cornea and improved visual acuity within two weeks after surgery. In the mean follow-up of 19.6 months, the ocular surface remained stable with no cicatricial complications.3

In 2003, another report of using the aforementioned amniotic membrane patching (AMP) for an acute ocular chemical injury appeared based on a three-center study out of Japan and Miami. Of the five cases in this study, four were grade II epithelial defects, the fifth was grade III. All cases experienced rapid pain relief after AMP, epithelialization of the cornea and improved visual acuity within two weeks after surgery. In the mean follow-up of 19.6 months, the ocular surface remained stable with no cicatricial complications.3

The early success of AMP set the stage for further investigation. Our group, together with Daniel Johnson, MD, from the University of Texas, San Antonio, in 2008 reported on the use of the temporary amniotic membrane patch via the ProKera device in the setting of acute corneal chemical burn. Again, this was a small series—five eyes in five patients—each receiving the amniotic membrane patch within eight days of their injury, with mean insertion at 3.7 days.4

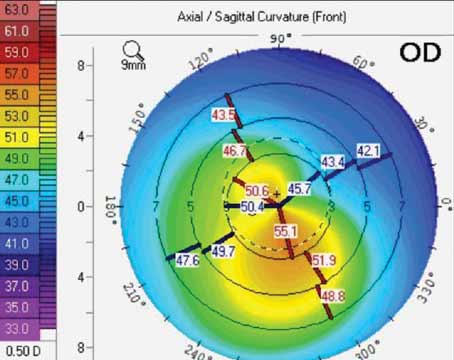

Two eyes in this group had total corneal epithelial defects, and the other three had 60 to 75 percent damage with limbal (120 degrees to 360 degrees) and conjunctival (30 to 50 percent) epithelial defects. We repeated the patching one to three times in three cases. On average, conjunctival defects reepithelialized in 8.2 days and limbal and corneal defects healed in 23.6 days. We completed the latter with circumferential closure of the limbal defects followed by centripetal healing of corneal defects. In three eyes, early peripheral corneal neovascularization was followed by marked regression after healing. In follow-up out to 16.8 months, all eyes retained a stable surface with improved corneal clarity, and without limbal deficiency or symblepharon.4

When to Apply AMP

Timing is critical for using amniotic membrane to repair a cornea damaged by a chemical burn. Our group has found that the sooner the better: Within two weeks of the injury is optimal, and the first week is better than the second. After two weeks the corneal damage is irreversible and amniotic membrane transplantation would have a limited effect.

The treatment of corneal burns has undergone a paradigm shift. Instead of using supportive therapy such as steroids and antibiotics, and sometimes even prayer, we can change the course of the injury early on by taking an active role in treatment.

Dr. Tseng is director of the Ocular Surface Center, medical director of the Ocular Surface Research & Education Foundation, and chief scientific officer of research and development of TissueTech Inc., Miami. He is the medical director of Bio-Tissue Inc., the maker of ProKera.

1. FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Division of Case Management, Office of Compliance and Biologics Quality. AmbioDry Amniotic Membrane Tissue Grafts (OKTOS Surgical Corp). June 23, 2005.

2. Meller D, Pires RTF, Mack RJS, Figueiredo F, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for acute chemical or thermal burns. Ophthalmology 2000;107:980-990.

3. Kobayashi A, Shirao Y, Yoshita T, Yagami K, Segawa Y, Kawasaki K, Shozu M, Tseng SCG. Temporary amniotic membrane patching for acute chemical burns. Eye 2003;17:149-158.

4. Kheirkhah A, Johnson DA, Paranjpe DR, Raju VK, Casas V, Tseng SCG. Temporary sutureless amniotic membrane patch for acute alkaline burns. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1059-1066.