Corneal cross-linking brought about a paradigm shift for keratoconus treatment. “Before this procedure was around, we’d have keratoconus patients getting gas-permeable lenses then scleral lenses and then transplants,” recalls Edward Manche, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and director of the cornea and refractive surgery service at Stanford University. “To have this technology that can save people from the need for invasive transplantation procedures is really remarkable. It’s an exciting time for cross-linking, and we’re just at the beginning of the journey.”

We spoke with several experts about the ins-and-outs of the cross-linking procedure. Here, they share their tips and insight on patient selection, protocols and the future.

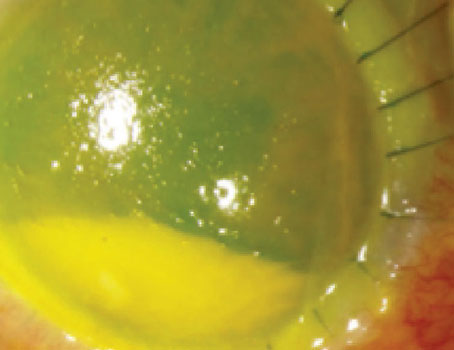

|

| A topographic map from the Pentacam of a 37-year-old patient with increasing refractive cylinder suggesting an irregular astigmatism with asymmetric bow tie and skewed radial axis. (Courtesy Brandon Baartman, MD) |

Identifying Early Keratoconus

The time to catch keratoconus is before any visible signs of the disease such as obvious coning, iron rings or Vogt striae are seen on physical exam. Posterior corneal elevation changes are some of the first early warning signs of keratoconus, with the classic pattern of inferior steepening. Less common appearances can also include central or superior steepening.

In addition to topography, clinicians use tomography to further analyze the shape of the eye. “Pentacam’s parameters, including the Belin Ambrósio Enhanced Ectasia Display score, help us differentiate between normal and abnormal corneal shape,” says William Trattler, MD, of the Center For Excellence In Eye Care in Miami.

This screening index analyzes both anterior and posterior corneal elevation. Two pachymetry profiles: corneal thickness spatial profile and percentage thickness increase assess how thickness is distributed across the entire cornea and how these changes progress, compared with the normal population.

According to Audrey R. Talley Rostov, MD, a partner at Northwest Eye Surgeons in Seattle, epithelial thickness mapping is an indispensable modality for keratoconus detection and evaluating potential cross-linking candidates. She says that epithelial mapping is a useful adjunct to tomography, particularly in borderline cases, because it can help to confirm irregular astigmatism or inferior steepening that may be unclear on tomography via a corresponding thin area seen on epithelial mapping.

“One of the earliest signs is thinning in the area of steepening,” she says. “The superior epithelium should be thinner than the inferior epithelium, and the inferior epithelium should be thinner than the center epithelium. If the inferior is thinner than the superior, you know that there’s a thin spot there and you want to be very suspicious for keratoconus. On the other hand, if you see thickening in the area of steepening area, then the patient may be an eye rubber or there could be some dry eye that’s looking like a false positive for keratoconus.

“This often comes up in patients who want refractive surgery,” she continues. “Patients come in for a refractive surgery evaluation, and they’re kind of borderline or their epithelial thickness mapping isn’t definitive or it’s a little iffy. Maybe there’s some asymmetric astigmatism. The first thing I do is treat dry eye. Dry-eye disease can masquerade as some inferior steepening. I have the patient come back and repeat the measurements. For patients with good best-corrected vision who aren’t interested in refractive surgery and were referred to me for some astigmatism, I’ll wait and see them back depending on their age. If it’s a younger patient, in the pediatric or adolescent age range, I’ll see them back in three or four months to check whether the dry-eye treatment resolved the issue. If it’s an older patient, it could be six months. If the patient is interested in refractive surgery and their epithelial thickness mapping looks borderline, I may offer an ICL instead of a laser vision correction treatment.”

“Be sure to do tomography and epithelial thickness mapping first before the patient has had drops in their eyes for the exam for the most accurate results,” she adds.

One of the newer keratoconus diagnostics available is genetic testing. While it’s not typically administered as part of a standard screening, one genetic testing scenario might be when a relative of a keratoconus patient is interested to know whether or not they might have the same condition. “Genetic testing isn’t a definitive diagnostic test,” cautions Brandon Baartman, MD, of Vance Thompson Vision in Omaha, Nebraska. “We still want to see other signs of keratoconus progression before we offer a cross-linking procedure. But we also know to maybe follow those patients a little closer if they have a positive genetic test and keep them on our radar.”

To Treat or Not to Treat?

When it comes to young keratoconus patients, treating early and immediately is the usual mantra—but how young is too young to cross-link? “This is a great debate among many anterior segment surgeons, particularly corneal surgeons,” Dr. Baartman says. “We’re asked that all the time, especially in our referral networks when there’s a young kid. Doctors see advancing astigmatism and worry about keratoconus. The FDA approval age is 14; however, the earlier the disease is treated, the better. We know that cross-linking is effective and that preventing the development of visually devastating keratoconus is a significant quality of life enhancer. I wouldn’t hesitate to treat a patient younger than 14 if there’s clear evidence of keratoconus and progression—even if it required, which in some cases it has, bringing a patient to a pediatric hospital and using general anesthesia to perform a bilateral same-day procedure. It’s very meaningful to that patient and family.”

Likewise, Dr. Rostov says, “If I’m really concerned about progression of disease in a pediatric patient, I wouldn’t necessarily wait for them to show a lot of progression, because that could risk vision loss.”

Fewer and fewer keratoconus patients today go on to require corneal transplants because of cross-linking. “Now, we’re trying to identify these patients at a younger age,” says Dr. Manche. “Most patients we end up seeing already have moderate to advanced disease and now need specialty contact lenses. There’s been a number of efforts to expand screening to younger people.” Dr. Manche is involved in a small company that’s developing an app with a phone adapter to help primary care doctors or pediatricians to identify possible keratoconus suspects for subsequent referral. “If we can identify patients earlier, and cross-link them to stabilize the cornea, we can hopefully get them in spectacles or soft contact lenses instead.”

Though keratoconus is usually first diagnosed in young and adolescent patients, the disease doesn’t limit itself, and neither does the treatment. “A few years back when I reviewed my—at that point about 1,000—cross-linking cases,” says Dr. Rostov, “I discovered that about a third of my patients who had cross-linking were over the age of 40. Cross-linking isn’t just for younger patients; you can actually get good results with older patients. In fact, despite some of the older myths out there, keratoconus can progress after age 40. I’ve seen a small spike in cases from the ages of 40 to 50. I’ve also seen progression, although rarely, in patients at age 50 or even 60. Again, it’s more unusual, but it can occur.”

“Age isn’t a factor,” agrees Dr. Trattler, who’s successfully treated a 79-year-old keratoconus patient and a patient in their 80s. “We found that in our patients who had a delay from the time they came in to see us to actually having a cross-linking procedure, of those 40 years and older, about 41 percent progressed at a rate of one diopter per year or more. So, just because a patient is 50, 60 or 70 doesn’t mean they can’t progress. Similarly, just because a patient has been stable for several years, doesn’t mean they’ll be stable forever. Consistent follow-up is important.”

Indeed, despite the much lower odds of keratoconus progression after age 40, the likelihood never reaches zero.1 In patients over 40, some mild posterior corneal steepening and thinning may occur, independent of normal age-related changes.2 Follow-up with corneal tomography is advised, as well as counseling to avoid eye rubbing.

While progressive disease is a call for prompt cross-linking, stable disease doesn’t warrant treatment in every single case, especially in older patients. Dr. Manche says that many of his older patients assume they need corneal cross-linking simply because they have keratoconus. “But we go back and look at their records, and they’ve had no change in their prescription or topography,” he explains. “Keratoconus can stabilize on its own. You don’t want to perform surgery unnecessarily on a patient in their 30s or 40s with long-standing but unchanging keratoconus. The FDA specifically approved cross-linking for the treatment of progressive, unstable keratoconus, so it’s important to make sure you’re not treating someone who’s already stable and not going to rapidly progress.”

Documentation

“Stabilizing an actively warping cornea is one of the most important things we can do for eye health, but for better or for worse, much of the decision to cross-link is dictated by what we know insurance will deem medically necessary,” Dr. Baartman says. “We practice in a climate where there’s an expensive procedure to perform and we also need to ensure we remain whole as a business while offering this.”

Not all commercial insurance plans cover the FDA-approved epithelium-off corneal cross-linking procedure; those that do usually have progression criteria such as an increase of 1 D in Kmax, astigmatism or myopia over 12 to 24 months.

“Sometimes the prior authorization comes back as a ‘no,’ and so then our plan is to follow the patient for an additional three months or so, depending on their age,” Dr. Baartman says. “If it’s a patient in their 40s, we’re not as concerned about rapid progression as we would be with a patient in their mid-teens. We bring the youngsters back pretty quickly to repeat those tests, and usually in those scenarios, if it’s true keratoconus that’s progressing as we suspect, there will be some changes we can notate that will allow us to move into the treatment phase.

“Generally, we look at some of the criteria that insurance deems important, such as a reduction in best-corrected visual acuity that we deem is the result of keratoconus,” he continues. “Other criteria might include an increase in corneal steepness or keratometry readings or progression of a refractive error.

“But at the end of the day, we also believe that no one is born with a keratoconic cornea,” he says. “We know that if we see one in the clinic, it hasn’t always been like that, so at some point it’s progressed. While we know cross-linking is medically necessary, the patient’s insurance company wants to see that too. The onus is on us to demonstrate that to them.”

Dr. Baartman says that this is one the of the main things his practice talks about when asked about how they conduct their keratoconus screenings. “You have to be an investigator when you get a keratoconus referral,” he says. “One of most valuable things you can do for that patient, and for your team and the doctor’s time, is to gather the patient’s prior ocular information, get referral notes, or if there aren’t any, call the patient so we know which doctors to call. We want to get as much information as we possibly can so that at the time of the evaluation, we can compare that to our current information. We don’t want to have to see them once and then wait a number of months to see them again to make our determination. Sometimes there’s a gray area if a patient wasn’t measured using the same tool, but I think we all agree that if there’s clear keratoconus and even the slightest bit of evidence, it’s worth considering that patient’s cornea unstable and ready to be cross-linked.”

Dr. Baartman notes that insurance coverage of cross-linking is more widespread today than in the past. “I’m spending a lot less time on the phone with insurance companies pleading the case, particularly in young individuals, so I think that probably points to increased awareness of the significance of the condition. But every once in a while, we’ll still need to demonstrate further progression to get a patient cross-linked.”

Patient Counseling

Many patients are under the impression that cross-linking is like a laser refractive procedure and that it’ll improve their vision, says Dr. Manche. “It’s important to emphasize that cross-linking is meant to stop keratoconus progression, not improve vision,” he says. “There’s typically not much improvement in vision.

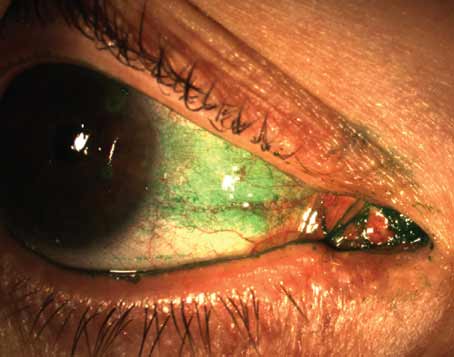

“We also have to warn patients of the risks associated with cross-linking,” he continues. “Patients may get transient corneal haze. Some will develop infectious keratitis, corneal ulceration, infections or even neurotrophic corneal neuropathy. That being said, without the treatment, patients are going to have progressive keratoconus. So, if they don’t get it treated, it’ll invariably worsen and then they’ll potentially need some type of corneal transplantation.”

Dr. Baartman says that on the day of the procedure, he spends most of the time talking about the disease. “While I don’t want to minimize the actual procedure itself, I make sure to talk about the etiology of keratoconus.” He says most of those patients are eye-rubbers, so he explains that eye rubbing weakens the cornea and that continuing to do so could compromise the cornea to the point that cross-linking re-treatment might not be enough. “I spend most of the time getting to the why of keratoconus and why stopping eye rubbing is important.”

“Eye rubbing can exacerbate the disease at any age, but especially in young patients,” Dr. Rostov points out. She adds that eye rubbing probably doesn’t cause keratoconus. “Plenty of patients who rub their eyes will have astigmatism but not keratoconus, and there are patients with keratoconus who don’t rub their eyes. It’s likely there’s a genetic predisposition in addition to the environmental eye-rubbing factor that contributes to keratoconus progression.”

Contraindications

Cross-linking isn’t advised in certain patients, such as those with insufficient corneal stroma. Those with the following may not be good candidates:

• Active infections. “A history of herpes keratitis is concerning because herpes can be reactivated with ultraviolet light,” Dr. Manche explains.

• Corneal scarring. “You may be able to stabilize the cornea in a patient with dense scarring, but if the scarring is too dense you’re not going to gain any benefit from the cross-linking and will need to do a transplant either way,” Dr. Manche says.

• Inability to cooperate. Patients who aren’t able to fixate on the light during the UV irradiation aren’t ideal candidates. “Theoretically, you could cross-link a patient under general anesthesia,” Dr. Manche says. “We don’t do that here at Stanford, but you could certainly do that.”

• Autoimmune diseases. “Sjogren’s or rheumatoid arthritis—those are conditions where you can get corneal melts and poor healing,” he says.

Some conditions may predict poorer outcomes with cross-linking. “A patient with advanced keratoconus can get some effect from cross-linking, but they’ll still be left with pretty significant distortion and will need specialty contact lenses,” Dr. Manche notes.

“Another condition that tends not to do as well with cross-linking is pellucid marginal degeneration,” he adds. “Cross-linking isn’t as effective, likely because the thinning is more peripheral and inferior as opposed to central or paracentral. Cross-linking treats the central 9 mm of the cornea, so quite possibly we’re not targeting the main weak areas of the cornea in a patient with pellucid marginal degeneration. There has been some work done with customized cross-linking, where it could be done more inferiorly in these cases, and that might improve efficacy.

“Patients who have corneal ectasia following keratorefractive surgery tend to do slightly less well with cross-linking than those with keratoconus,” Dr. Manche says. “We aren’t sure why cross-linking isn’t as effective in post-LASIKPRK/SMILE ectasia, but in my experience, there isn’t as much flattening of the cornea.”

Patients who rub their eyes after cross-linking are at increased risk for needing a second treatment, Dr. Trattler points out. “In our experience, the need for second treatments is about one to two percent,” he says. “Follow-up after cross-linking is important, every six to 12 months to monitor the shape of the cornea. The good news is retreatments are very safe and effective.”

The Current Cross-linking Procedure

Cross-linking uses a photosensitizer (such as riboflavin) and an UV-A light source to create a photochemical reaction that strengthens the chemical bonds of collagen fibrils in the cornea. The cross-linking process also occurs naturally with age, which is why keratoconus is thought to stabilize as patients get older. For both procedural and age-related processes, oxygen availability is key.

The FDA-approved iLink procedure with the KXL System, first involves epithelial debridement under topical anesthesia to approximately 9 mm. One drop of riboflavin (Photrexa Viscous, riboflavin 0.146% 5’-phosphate in 20% dextran ophthalmic solution) is then applied topically every two minutes for 30 minutes. The eye is observed for yellow flare. If no flare is detected, one drop of Photrexa Viscous is instilled every two minutes for an additional two to three cycles until yellow flare is observed. If corneal thickness is less than 400 µm, hypotonic Photrexa (0.146% riboflavin 5’-phosphate ophthalmic solution) is instilled every five to 10 seconds until corneal thickness is at least 400 µm. Finally, the eye is irradiated at 3 mW/cm2 at a wavelength of 365 nm for 30 minutes, with continued instillation of one drop of Photrexa Viscous every two minutes for 30 minutes.

“We use the FDA-approved Glaukos technology to cross-link patients,” says Dr. Trattler. “We do a variation of the continuous 30-minute UV light where we pulse the light, on for 15 seconds and off for 15 seconds. While the amount of energy can’t be changed, the time of the procedure can be. For example, for a patient with thin corneas—let’s say 200 µm—and advanced keratoconus, instead of doing a full 30-minute treatment, you could certainly achieve an effect in 15 or even 10 minutes of UV light exposure because the cornea is so thin that the full 30 minutes aren’t necessary.”

Most surgeons use a 400-µm cutoff for cross-linking but, as Dr. Trattler notes, some thinner corneas can undergo cross-linking as well. “Different doctors use different cutoff points,” Dr. Manche notes. “Intraoperatively, you can swell the cornea using hypotonic saline or hypotonic riboflavin. The cornea soaks it up like a sponge. After epithelium removal and installation of the riboflavin, check the pachymetry. If it’s less than 400 µm, you want to then swell the cornea. If you’re starting at less than 400 µm, you can run into situations where you can’t swell the cornea enough, and then you might be in a situation where it’s unsafe to perform cross-linking. If the cornea is significantly thinner, such as 370 µm or less, these patients typically won’t be good candidates for epithelium-off cross-linking. They’d benefit from epithelial-on cross-linking. Though it’s not yet FDA approved, there are a number of protocols that have been employed.”

Corneal cross-linking is sometimes performed in advance of refractive surgery to achieve better visual outcomes or in combination with intrastromal corneal ring segments. In the case of the former, Dr. Rostov says, “I always tell patients that the goal of cross-linking is to prevent progression of disease. It’s not to reverse disease that’s already there. Cross-linking often produces some mild flattening of the cornea, which can give patients a better fit for glasses or contact lenses to improve best-corrected vision. Some patients who have keratoconus with mild progression want a topography-guided treatment later on. If they have cross-linking first, we can then potentially do a topography-guided treatment to improve their vision—not in all cases, but in some.”

Intacs were originally approved for treating low myopia. “They were pretty much abandoned once excimer lasers were introduced,” Dr. Manche says. “Now, they’ve been repurposed to try to regularize the corneal curvature, and they can be quite effective in some cases.”

While Intacs help regularize the corneal shape, helping reduce astigmatism and irregularity, they don’t stabilize the cornea. Dr. Manche says, “In our system, what we typically do is perform cross-linking first to allow for corneal remodeling and reshaping, and then, depending on the patient, we’ll insert Intacs ring segments. I don’t think there’s a right or wrong order in which to do the procedures. Some people perform cross-linking after Intacs, and others do combined. The way I look at it is that with cross-linking, you get some flattening—usually 1 to 1.5 D—but occasionally you get quite a bit of flattening, and some shifts in the orientation of steepness or axis of irregular astigmatism. When you place the Intacs, you’re using that data not only for the placement of the rings but also for their dimensions.”

Dr. Trattler doesn’t implant Intacs. “Most of our patients who get cross-linked will get improvement in corneal shape over months and years,” he says. “Some doctors feel that Intacs could be additive, but I certainly see patients’ improvement over time [with only cross-linking]. We also recommend scleral contact lenses for patients with moderate to advanced keratoconus, and these patients see well. So, if a patient has moderate to advanced keratoconus, you can put Intacs in and they’re still going to need scleral contact lenses. Intacs won’t change that need. So, we focus on the cross-linking procedure. Our main additional procedure is the ICL for patients who have improvement in corneal shape, a decrease in astigmatism and reasonably good BCVA. We use the ICL to get rid of a lot of myopia.”

Dr. Baartman says he used to implant Intacs in certain patients, such as those “who have more mild disease and a shift of the cone where an Intacs ring might be able to centralize some of the aberration profile that developed from inferior steepening.” He created the channel for the Intacs ring or rings using a femtosecond laser, placed the rings and then debrided the epithelium and proceeded with cross-linking.

“I’ve stopped doing that as frequently, largely because of the quality of vision that a lot of patients are getting from scleral lenses,” he continues. “A lot of our referral network had made mention of the fact that sometimes after Intacs, it’s harder to fit a good scleral lens. So, if somebody was going to be in a scleral lens anyway, it probably didn’t make sense for us to be putting in Intacs. On rare occasions, I’ll still consider it, but much less frequently, with the widespread acceptance of scleral lenses and excellent visual acuity patients are getting.”

He says scleral lenses are his third stage for a keratoconus visual rehabilitation treatment plan. “The first thing is corneal stabilization,” he explains. “A concern could be, ‘Well, a patient is already in scleral lenses. Do they need to be cross-linked?’ The answer is probably still yes. We want to, in essence, re-strengthen the cornea to a level at which it’ll stop progressing, to maintain what the patient has in scleral lenses, even if they’re already seeing well in scleral lenses. I think that’s the perfect time to cross-link. Once you go through that stage of treatment in both eyes, and the second stage of healing—management of epithelial closure and early pain and vision rehabilitation—then you go to long-term vision rehabilitation with things such as scleral lenses or consideration of topography-guided ablations, in the right corneas.”

Dr. Baartman adds that there are a number of protocols that have been developed for simultaneous or staged cross-linking with corneal refractive procedures—mainly PRK since it’s more tissue-sparing than LASIK. “My current protocol is to approach stabilization first using cross-linking and ensure that we’ve demonstrated stability—I like a course of at least nine to 12 months,” he says. “Then we can consider vision correction or vision rehabilitation measures like topography-guided ablations, in the scenario where it makes sense: enough corneal tissue and a motivated patient who accepts the need for remaining in glasses or contacts but wants some improvement in the overall correction or quality of vision in that correction. In that scenario, topography-guided ablations can be really beneficial. I don’t commonly do simultaneous in my practice, like the Athens protocol, but is something to be considered as cross-linking device technology continues to improve.”

Postop Management

Ensuring rapid healing of the epithelium is the main goal following epithelium-off cross-linking. “A bandage contact lens is used, and patients are placed on antibiotic drops [usually fluoroquinolones] for prophylaxis,” explains Dr. Trattler. “Patients receive a topical steroid and can use an NSAID for pain. The eye should heal over a period of about three to five days.”

Sometimes there’s delayed re-epithelialization due to anatomical issues such as floppy lid syndrome or an external disease. “For whatever reason the patient is taking a long time to heal, sometimes amniotic membrane grafting or a temporary tarsorrhaphy is needed,” Dr. Manche says.

Epi-on Anticipation

Most surgeons agree that a major challenge of the current approved cross-linking procedure is the need for epithelial debridement and subsequent re-epithelialization healing stage. An advantage of epithelium-on cross-linking is much faster healing. While patients will still need to recover from a UV insult to the cornea, Dr. Manche explains, even with a bandage lens, they’ll still heal faster than if they’d had epithelial debridement. “Without an epithelial defect, the risk of infectious keratoconus is drastically reduced and the visual rehabilitation is significantly better,” he says. “Patients usually get back to work faster and it doesn’t have as much impact on their vision. If epithelium-on cross-linking works as well as epithelium-off—that’s a bit caveat—I think it’ll become the procedure of choice and cut down on the morbidity of the procedure as well as the time required of both the health-care professionals and the patients.”

“It’s going to change the landscape completely,” says Dr. Trattler. “I think that once we start doing epithelium-on cross-linking, we’ll never go back to epithelium-off. It’ll be standard of care once it’s approved.”

Dr. Rostov consults for Glaukos and Zeiss. Dr. Manche consults for Zeiss. Dr. Trattler consults for Glaukos and has a financial interest in Epion Therapeutics. Dr. Baartman is a consultant and investigator for Glaukos.

1. Kollros L, Torres-Netto EA, Rodriguez-Villalobos C, et al. Progressive keratoconus in patients older than 48 years. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2023;46:2:101792.

2. Hashemi H, Asgari S, Mehravaran S, et al. Keratoconus after 40 years of age: A longitudinal comparative population-based study. Int Ophthalmol 2020;40:3:583-589.