Presentation

A 17-year-old Caucasian boy presented for oculoplastic evaluation for bilateral ptosis. He was referred after his primary eye-care provider noticed ptosis on routine exam.

The patient reported no visual difficulty from the ptosis and no diplopia. According to the parents, the ptosis had been present for years and did not appear to be acutely worsening. They denied any major variability of the ptosis. However, the patient has been told his entire life that he looks "sleepy."

Medical History

The patient reported no medical problems, and he was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He was a full-term baby with an uncomplicated delivery and no birth trauma. Family history was negative for ptosis. He had no allergies and review of systems was negative.

Examination

His ocular examination revealed a Snellen visual acuity of 20/25 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left. His pupils were normally reactive with no relative afferent pupillary defect. Visual fields showed a superior altitudinal defect in both eyes that resolved when the lids were elevated. On external exam ptosis was noted bilaterally with a margin reflex distance 1 of +1 in the right eye and zero in the left eye (See Figure 1). Extraocular movements were limited in all directions of gaze, affecting both eyes symmetrically. Levator function was measured at 12 mm in both eyes (See Figure 2). His intraocular pressures were within normal limits. Slit lamp examination was white and quiet.

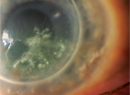

On dilated fundus exam there were subtle pigmentary changes in the mid-periphery with mild dropout of the RPE in both eyes inferiorly (See Figure 3). Both optic nerves demonstrated an increased cup-to-disc ratio with healthy appearing rims. The macula, vessel and vitreous were normal in both eyes.

Diagnosis, Evaluation and Treatment

An EKG performed on the day of presentation revealed bradycardia with a normal PR internal indicating the absence of heart block. Cardiology further evaluated the patient with home Holter monitoring and no abnormal events were detected. Although there was no evidence of cardiac conduction abnormality, cardiology recommended yearly EKG with close observation.

At the time of publication, the patient and his family were strongly considering ptosis surgery. During the procedure, a muscle biopsy will be taken in order to determine if the patient has the mitochondrial deletions consistent with Kearns-Sayre Syndrome.

Discussion

Kearns-Sayre syndrome is a rare mitochondrial disease with both ophthalmic and systemic manifestations. It was first described in 1958 as a triad of pigmentary degeneration of the retina, external ophthalmoplegia and atrioventricular heart block.1 Today the syndrome is characterized as a chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia with pigmentary retinal degeneration, onset prior to age 20 and at least one of the following: heart block; cerebellar ataxia or increased protein in the cerebrospinal fluid.2

One of the first symptoms of KSS is ptosis. Therefore it is often the ophthalmologist who initially makes the diagnosis. The ptosis is progressive, leading to poor levator function with superior visual field defects. Despite the ptosis, most patients often have good visual acuity.3

Ophthalmoplegia is one of the characteristic signs of KSS. It is described as chronic progressive, and in most cases ocular motility becomes more restricted with age. The restriction in movement is typically symmetric, thus few patients report diplopia.

The classic pigmentary retinopathy seen in KSS is often described as a mottled "salt and pepper" pattern of pigment clumping. Typically it is seen in the posterior fundus and peripapillary zone. These changes can be very subtle, making them difficult to detect. The characteristic features of retinitis pigmentosa such as optic nerve pallor, "bone spicule" pigment formation, attenuation of retinal vessels and posterior cataracts are rarely seen. Other ophthalmic complications of KSS include loss of

The systemic complications of KSS vary widely from patient to patient. The most concerning complication is complete atrioventricular block that can lead to sudden death. One paper noted that 57 percent of KSS patients have some clinical manifestations of cardiac disease.4 Treating these patients is challenging as there is little consensus on when to place pacemakers and how frequently they should have cardiac monitoring. Patients can have a normal EKG and develop life-threatening arrhythmias with little to no warning. In the cardiology literature, there have been case reports of patients developing complete heart block within 10 months of a normal documented EKG.2

Other systemic manifestations that should be monitored include: diabetes mellitus; thyroid dysfunction; hypoparathyroidism; hyperaldosteronism; ataxia; hearing loss and dementia. These complications can develop at anytime during the course of the disease.

Although KSS is often a clinical diagnosis, it can be confirmed by southern blot analysis of muscle biopsies looking for characteristic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations. Some studies have noted that mutations in nuclear tRNA can be seen in KSS. On histopathology affected muscles have the typical "ragged" fiber appearance.3

Mitochondrial diseases have a maternal inheritance pattern; however, most patients with KSS develop the disease sporadically and have no family history of KSS. In female patients with KSS it is important to remember the maternal inheritance pattern of mitochondrial diseases in order to appropriately counsel patients on the potential for offspring developing KSS.

In cases of sporadic KSS, it is thought that the mtDNA mutation occurs spontaneously in the ovum or zygote. Thus the mutation is passed to other generations of cells in a random fashion, resulting in a heterogeneous distribution of the normal and mutated mtDNA.5 This may account for the numerous phenotypes expressed by patients with KSS. A second factor to consider is that the mutated mtDNA is usually shorter than the normal mtDNA, allowing it to replicate faster. The ratio of normal to mutated mtDNA determines whether or not the cells' function will be affected. With time the mutated mtDNA will accumulate. Thus cells that once had normal mitochondrial function can no longer be maintained. This may explain the progressive clinical course of worsening ptosis and ophthalmoplegia seen with KSS.

In conclusion, it is important to note that KSS is a progressive disease in both its ophthalmic and systemic manifestations. When there is a triad of ptosis, ophthalmoplegia and pigmentary retinopathy, a diagnosis of Kearns-Sayre should be considered and an EKG should be done to rule out the life-threatening complication of A-V block. Patients should be counseled that only females can pass along KSS to their offspring due to mitochondrial transmission. Predicting the rate of progression is challenging as the phenotypic expression of the disease is quite varied. However with careful monitoring and a multi-disciplined approach, the morbidity and mortality of this rare disease can be reduced.

The author would like to acknowledge Jacqueline Carrasco, MD, of the Oculoplastic Department at Wills Eye Institute for her assistance with this manuscript.

1.

2. Chawla S, Coku J, Forbes T, Kannan S. Kearns-Sayre syndrome presenting as complete heart block. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29:659-662.

3. Park SB, Ma KT, Kook KH, et al. Kearns-Sayre Syndrome—3 case reports and review of clinical features. Yonsei Medical Journal 2004;45:727-735.

4. Welzing L, von Kleist-Retzow JC, Kribs A, et al. Rapid development of life-threatening complete atrioventricular block in Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 2008 Sep 24. [Epub ahead of print]

5.