Presentation

A 16-year-old female presented to her general ophthalmologist complaining of mild redness, blurry vision and pain in her left eye, which had progressed over two days after removing her orthokeratology rigid gas permeable contact lenses. She had not worn the contact lenses after first experiencing these symptoms. The ophthalmologist started Ocuflox q.i.d. She improved for one week, but then began to feel worse. Ocuflox was stopped, and she was prescribed Pred Forte 1% q.i.d. and Cyclogyl 1% t.i.d. She showed slow improvement over the next few visits, but a clinical change was noted after two weeks, and there was a suspicion for herpes simplex keratitis. Her ophthalmologist started Viroptic q2hr, as well as a Pred Forte taper. After one day of this therapy, her pain and photophobia worsened, and she was referred to the Wills Eye Cornea Service for evaluation. She denied using topical anesthetics at home.

Medical History

The patient's ocular history included wearing orthokeratology RGP contact lenses overnight to correct myopia for the past four years. She used Unique pH cleaning solution and AMO Complete soaking solution, after which she rinsed them with tap water and inserted them into her eyes. She denied wearing contact lenses while awake and swimming in them. Prior to her presentation, she had never had an ocular infection. The patient reported no past medical history and no seasonal allergies.

Examination

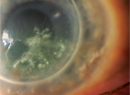

Office examination revealed a visual acuity of 20/20 in the right eye and counting fingers at 2 feet in the left eye. Her pupils were round, equal, briskly reactive, and without a relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility and confrontational visual fields were full in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were 13 mmHg OD and 14 mmHg OS. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the right eye was normal, and examination of the left eye revealed a deep, ring-shaped corneal infiltrate measuring 6.3 mm vertically and 7.2 mm horizontally, with an overlying epithelial defect measuring 3.7 mm vertically and 6.5 mm horizontally (See Figures 1a and b). The cornea was minimally thinned (~5 percent) in the area of the infiltrate. She had a 0.3 mm hypopyon and keratic precipitates. Fundus examination of the right eye was normal. The corneal pathology obscured any view of the posterior pole of the left eye. B-scan of the left eye showed no vitritis, mass or retinal detachment.

Diagnosis, Workup and Treatment

Corneal scrapings were performed and sent for pathology and microbiology. Given the high clinical suspicion for Acanthamoeba keratitis, she was empirically started on Baquacil q1hr around the clock as well as Atropine 1% t.i.d. and Bacitracin ointment q.i.d. Gram stain showed white blood cells with no organisms, and there was no preliminary growth in the corneal cultures. Over the next three days, she showed mild improvement in symptoms, her exam remained stable, and Baquacil was continued at every hour only while awake.

After one week of this treatment, the corneal infiltrate and epithelial defect were mostly unchanged, but the hypopyon had resolved and the patient's pain had improved. Corneal scrapings were repeated, and Acanthamoeba cysts were identified, confirming the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis (See Figure 2). At two and three weeks follow-up, her pain was mildly reduced, but the patient still had severe photophobia. The exam showed mild thinning at the edge of the ulcer and stromal neovascularization. Baquacil was decreased to q2hr, and Brolene was added, also at a frequency of q2hr. The patient was monitored on a weekly basis while her discomfort and epithelial defect slowly improved. However, the central area of the stromal infiltrate became more opacified, and her vision remained poor. The anterior surface of the cornea developed calcification, and there was a persistent epithelial defect (See Figure 3A and B). At the time of this report (2.5 months after presentation to Wills), the frequency of Brolene and Baquacil had been decreased to six times per day, and Lotemax b.i.d. was recently added. The patient was counseled about her poor visual prognosis and that a penetrating keratoplasty may be necessary in the future. However, medical therapy will be continued as she slowly improves.

Discussion

Acanthamoeba keratitis, first described in the 1970s, has been increasing in incidence over the past few years in association with the use of multipurpose solutions and soft contact lens wear. Some reports estimate the infection rate to be about one in 10,000 contact lens wearers annually, but recent studies suggest an increased incidence of new cases. Contact lenses have been associated with 85 to 95 percent of cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis and remain the most common risk factor. Poor contact lens hygiene is often observed in these patients, but not in all cases. A variety of other contact lens-related risk factors have been identified, including swimming in lenses, inadequate disinfection, tap water rinse, minor corneal trauma and exposure to contaminated water. Also of note, all commercially available multipurpose contact lens solutions are ineffective against Acanthamoeba.

Soft contact lens wearers are at a 9.5 times greater risk of Acanthamoeba keratitis than rigid lens wearers. However, many recent reports have shown a high rate of infection in patients who use orthokeratology, a practice that employs a rigid contact lens overnight to alter corneal shape and provide temporary correction of myopia. The first 50 cases of microbial keratitis reported in orthokeratology revealed an exceptionally high frequency (30 percent) of Acanthamoeba, which was attributed to poor lens care, patient non-compliance and wearing lenses despite discomfort. This practice has increased since the late 1990s, especially in

Making the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis is challenging, as it is usually mistaken for herpes simplex keratitis. The classic clinical finding is a ring-shaped, corneal stromal infiltrate, but this is a late manifestation. Early findings can include epithelial keratitis, radial keratoneuritis and stromal infiltrates, which often lead to misdiagnosis as herpetic keratitis. The key is to have a high clinical suspicion, especially in contact lens wearers diagnosed with herpes simplex keratitis who have significant pain and respond poorly to treatment. Multiple studies have demonstrated that a delay in diagnosis leads to a poor visual outcome and a more severe, prolonged clinical course. To confirm a suspected diagnosis, corneal scrapings are stained with Giemsa, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), hematoxylin and eosin, Wright's, calcofluor white or acridine orange to look for amoebic double-walled cysts and trophozoites. Acanthamoeba can be cultured on non-nutrient agar with Escherichia coli overlay, but cultures are often negative. Confocal microscopy can also be helpful in making the diagnosis.

Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis is difficult given that the cystic form is highly resistant to antimicrobial therapy. The standard treatment includes polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02% (PHMB, Baquacil) or chlorhexidine 0.02%, which is often combined with a diamidine, propamidine 0.1% (Brolene). These drops are administered every hour around the clock for the first few days, and then slowly tapered over months. Topical cycloplegic and pain control are given. A mild topical corticosteroid is sometimes used to control inflammation after the infection has shown significant improvement. Penetrating or lamellar keratoplasty in an eye with active infection usually has a poor prognosis. However, quiet eyes that have been successfully treated have a good visual outcome with surgical intervention, usually 20/40 or better, based on one study.

Our patient's clinical course demonstrates the diagnostic and treatment challenges of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Although she had known risk factors of orthokeratology and using tap water to rinse her lenses, she was misdiagnosed upon initial presentation to her ophthalmologist. Even after months of appropriate therapy, she has poor vision with a persistent epithelial defect and a large central corneal infiltrate.

The frequency of Acanthamoeba keratitis has been increasing and the most common association is frequent-replacement soft contact lenses. It is crucial to maintain a high clinical suspicion, as the best chance for a good visual outcome is early diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Baker would like to thank Elisabeth Cohen, MD, and Hall Chew, MD, both of the Wills Eye Institute Cornea Service, and Ralph Eagle, MD, Wills Department of Pathology, for their assistance with this case.

1. Awwad ST, Parmar DN, Heilman M, Bowman RW, McCulley JP, Cavanagh HD. Results of penetrating keratoplasty for visual rehabilitation after Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1080-1084.

2. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Acanthamoeba Keratitis Multiple States, 2005–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:532-534.

3. Hammersmith KM. Diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2006;17:327-31.

4. Joslin CE, Tu EY, McMahon TT, Passaro DJ, Stayner LT, Sugar J. Epidemiological characteristics of a Chicago-area Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreak. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:212-7.

5. Joslin CE, Tu EY, Shoff ME, Booton GC, Fuerst PA, McMahon TT, Anderson RJ, Dworkin MS, Sugar J, Davis FG, Stayner LT. The association of contact lens solution use and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:169-180.

6. Thebpatiphat N, Hammersmith KM, Rocha FN, Rapuano CJ, Ayres BD, Laibson PR, Eagle RC Jr., Cohen EJ. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A parasite on the rise. Cornea. 2007;26:701-6.

7. Watt K, Swarbrick HA. Microbial keratitis in overnight orthokeratology: Review of the first 50 cases. Eye and Contact Lens: Science and Clinical Practice 2005;31:201-8.