Presentation

A 31-year-old woman presented to the general clinic at Wills Eye Hospital with the complaint of blurred vision in both eyes and difficulty seeing at night. According to the patient, her symptoms had been slowly progressive over the past few years. She had never seen an ophthalmologist or optometrist for a complete eye exam, nor had she needed previous spectacle correction.

Medical History

The patient's medical history is significant only for asthma and migraine headaches for which she takes albuterol and occasional NSAIDs. She is also taking oral contraceptives. Her allergies are to ciprofloxacin and penicillin. She does not smoke, uses occasional alcohol, and has never used intravenous drugs. Her family history is significant for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Graves' disease, coronary artery disease and cancer (ovarian, pancreatic).

Examination

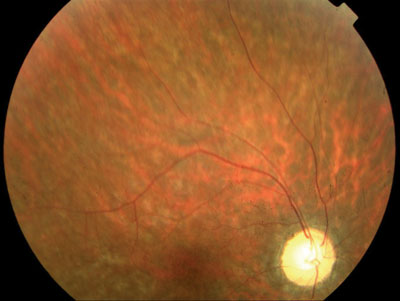

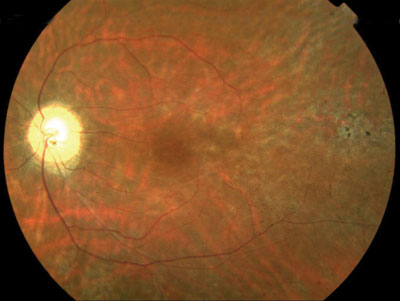

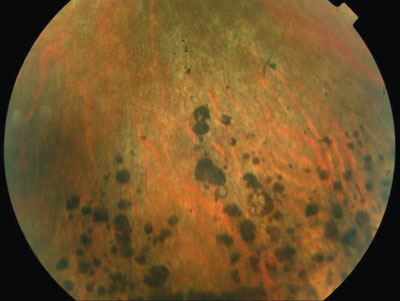

Office examination revealed a woman of short stature with an uncorrected visual acuity of 20/40 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye. She pinholed to 20/30 in the right eye with no improvement in the left, however her acuity could not be improved with spectacle correction. Her pupillary reactions were moderately brisk in each eye with no relative afferent defect. Extraocular motility was limited in each eye to the following: elevation of 10 percent, abduction of 30 percent, adduction of 20 percent, and depression of 70 percent. Her visual fields were full by confrontation. Intraocular pressures were 22 mmHg in both eyes by applanation tonometry. Slit-lamp examination was significant only for bilateral ptosis, with a marginal reflex distance of 0 mm in each eye and pronounced brow lifting. (Upon further questioning, the patient admitted her ptosis had been present since her early teens and had progressively worsened since then. See Figure 1.) Her dilated fundus exam is shown below (Figures 2, 3 and 4), and is significant for peripapillary atrophy, vascular attenuation and peripheral pigmentary changes.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 1. External photo demonstrating bilateral ptosis and significant brow lifting. | Figure 2. Color fundus photo of the right eye demonstrating peripapillary atrophy and vascular attenuation. | Figure 3. Color fundus photo of the left eye demonstrating peripapillary atrophy, vascular attenuation and salt-and-pepper pigmentary changes. | Figure 4. Representative fundus photo of pigmentary changes seen in the periphery of both eyes. |

What workup would you pursue? What is your working diagnosis? Please turn to p. 98

Diagnosis and Workup

The patient's history and examination, including progressive ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia and pigmentary retinopathy, are consistent with a diagnosis of chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO). An urgent cardiology consult with emphasis on electrophysiology (eg. EKG, Holter monitor) is required in these patients to rule out cardiac conduction defects. A skeletal muscle biopsy of the upper arm or leg may be required to confirm the diagnosis in uncertain cases.

Discussion

CPEO is the most common mitochondrial disorder to affect ocular muscles, with Kearns-Sayre syndrome being its best-known subtype. Less common mitochondrial myopathies of ophthalmic importance include myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers (MERRF), mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like syndrome (MELAS), and mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy.

Ocular manifestations of CPEO include ptosis followed by a progressive and symmetric loss of ocular motility in all directions, orbicularis weakness, and marked delay of saccades. Downgaze is usually well-preserved until late in the disease, as was the case in this patient. Despite the limitations in ductions, patients rarely complain of diplopia. Smooth muscle is not affected in this disease, and thus pupillary reactions and accommodation are preserved. Other associations include pigmentary retinopathy, optic atrophy, hearing loss, conduction defects, arrhythmias, dilated/hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, dementia, seizures, ataxia, short stature, diabetes mellitus, hypoparathyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, respiratory failure and gastrointestinal motility problems.

Kearns-Sayre syndrome is characterized by the triad of external ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinopathy, and cardiac conduction defects within the first two decades of life. Less-common features including cerebellar dysfunction and an elevated CSF protein (usually exceeding 100mg/dl) may be present. Peripapillary atrophy and salt-and-pepper retinal pigment epithelial changes are most striking in the posterior pole. However, true bone spicules, such as those seen in retinitis pigmentosa, are not typical. Histopathologically, these findings suggest a dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium rather than photoreceptor disease. A baseline cardiac evaluation, along with periodic checkups, is critical to rule out cardiac conduction defects. Typically, conduction defects occur 10 years after the appearance of ptosis and may result in sudden death.

Skeletal muscle biopsies may be obtained to aid in diagnosis. Pathology of such specimens reveals classic changes of a mitochondrial myopathy, including "ragged red fibers" that stain red or purple with a modified Gomori trichrome stain. The mitochondria of the involved muscle fibers may show increased staining for the enzyme succinate dehydrogenase. The mitochondria are concentrated peripherally and may demonstrate ultrastructural differences in the number, shape, or regularity of cristae. They are often increased in number and size as well.

Treatment of CPEO has been aimed at enhancing oxidative phosphorylation by repleting deficient substrates. Coenzyme Q10, essential for normal mitochondrial function, has been shown in some studies to improve exercise tolerance, cardiac function, and ataxia. However, no improvement in ophthalmoplegia, retinopathy or ptosis has been reported. Other treatments, such as thiamine, are more theoretical and have no proven benefit. It should be noted that steroids should not be used in these patients, as its use has been reported to precipitate hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma.

A careful surgical approach must be used when dealing with complaints of ptosis in these patients. The goal of surgery is to correct for the visual obstruction rather than the cosmetic appearance. Overly aggressive lid surgery may result in exposure keratopathy and corneal ulceration due to a weak orbicularis muscle and poor Bell's reflex. Strabismus surgery has been done successfully to alleviate symptomatic ocular deviations.

Dr. Fintak is a senior resident at Wills Eye Hospital. He would like to acknowledge the assistance of William Tasman, MD, and Edward Jaeger, MD.