This September, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the most advanced insulin-management system yet: a “hybrid closed-loop” system that combines a glucose monitor and an insulin pump in one device, requiring far less management by the patient. Because it functions in a manner somewhat similar to a healthy pancreas, the MiniMed 670G, made by Medtronic (Dublin, Ireland), has been nicknamed the “artificial pancreas.” The system, which the FDA has approved for use in people with Type 1 diabetes over the age of 14, is designed to maximize the amount of time a patient’s blood glucose levels stay within the desired target range. The system also allows patients and doctors to choose customized levels of automation to accommodate the patient’s health needs and lifestyle.

How the System Works

“A hybrid closed-loop system is the first phase of an artificial pancreas,” says Richard Bergenstal, MD, principal investigator of the pivotal study of the MiniMed 670G system, executive director of the Park Nicollet International Diabetes Center in Minneapolis, Minn., and a past president of the American Diabetes Association. “It’s considered to be the first phase because the individual still interacts with the system.”

|

| The MinimMed 670G insulin delivery system will allow an insulin pump (black device, above) to be automatically controlled by a glucose monitoring device the patient wears (smaller white object). |

“The ‘hybrid’ part is that the patient still interacts with the system to tell it that he’s about to eat, so it can provide some extra insulin,” he continues. “On its own, the system can’t quite keep up with the fluctuations triggered by a meal. It knows how much insulin to give, but it needs a little head start. So the individual tells the system how much carbohydrate he expects to eat, and the pump takes over from there. If the estimate turns out to be a little off, the pump can compensate for the error.”

Dr. Bergenstal says the system is designed to adapt to the needs of each individual. “It will reset your total amount of insulin, or the rate of insulin delivery over the course of the day,” he says. “That’s really good, because sometimes people are in a period of less activity or more stress—various situations in which their insulin requirements are going up or down. The overnight control, where the pump is working entirely on its own, has been particularly striking. It really keeps the blood sugar level down. Patients reliably start off every morning with good blood sugar levels, having had a safe night. Most of us see that as one of the biggest advantages of this system.”

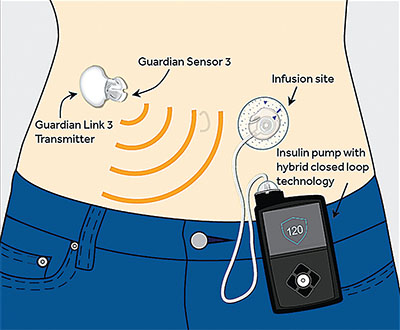

|

| The MiniMed 670G system’s glucose sensor interacts automatically with its insulin pump, minimizing the monitoring required by the patient. |

The Pivotal Trial

The recent FDA approval followed a pivotal safety study headed by Dr. Bergenstal that was completed this spring. Dr. Bergenstal says the study was conducted at 10 sites, nine in the United States and one in Europe; he describes it as a basic before-and-after treatment study. “This was not a randomized trial,” he notes. “Those have been done in the past by other groups around the world. The FDA wanted a study done in the U.S. with a large number of patients to demonstrate that the hybrid system is safe and effective.

“Our trial involved 124 subjects ranging in age from 14 to 75, who used the system at home for three months without any close monitoring,” he continues. “The participants had an average A1C level of 7.4 at the outset, which isn’t bad. Nevertheless, they improved to 6.9 by the end of the trial, and the amount of hypoglycemia went down as well, with no occurrences of severe hypoglycemia and no ketoacidosis. This was the largest and longest trial to date using a hybrid closed-loop system; the results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in September.”1

Dr. Bergenstal notes that without a system like this, it’s very difficult to achieve target blood glucose levels and keep them steady. “The current data in the Type 1 community suggests that somewhere around 30 percent of people are reaching these targets,” he says. “In our study, between 60 and 70 percent of the participants achieved those levels.”

Dr. Bergenstal adds that the system received FDA approval in record time. “We finished the study in the spring of this year, and Medtronic submitted for approval in June,” he says. “They got approval in September. However, the system isn’t on the market yet; it will be marketed sometime in 2017.”

Ophthalmologist’s Perspective

Clearly, improved management of Type 1 diabetes could have a positive impact on ocular consequences associated with the disease, including diabetic retinopathy. “I think that for young, motivated people, a system like this will make a difference,” says Gaurav K. Shah, MD, a partner at The Retina Institute in St. Louis, Mo. “We know from experience with diabetic retinopathy that we want the patient to have a good, sustained blood sugar level. The question is, will there be glitches? Will there be cost issues? Will insurance carriers cover it?

“I’m also concerned that if a patient is feeling good and his blood sugar levels are steady, the patient might conclude that all of his diabetes-related problems are doing OK,” he continues. “It might give people a false sense of security, leading them to be less likely to come in for regular checkups. Even if the diabetes is controlled, there are other things going on with these patients. And of course we don’t know what issues will arise with this technology over the long run, five or 10 years down the road.”

|

| The MiniMed pump is small enough to be attached to the patient’s belt, slipped into a pocket or hidden underneath clothing. |

Dr. Shah notes that only a few of his current patients use the monitors and pumps that are already available. “That’s because a lot of insurance carriers either don’t cover them or the patient has a lot of out-of-pocket costs,” he explains. “Not as many people are using the current systems as we would like.

“The other problem is, nowadays people are switching insurers frequently,” he adds. “One carrier may cover it while another does not. The new system could also have some of these issues. In addition, some of our patients may not be able to afford the out-of-pocket costs, or may have trouble understanding how to operate the system, or may not have the wherewithal to fight the carriers regarding eligibility. Nevertheless, I would absolutely recommend it to patients if they can afford it, if I know they’ll be compliant with office visits.”

Outlook: Promising

“I think a system like this will have a major impact on Type 1 diabetes, in multiple ways,” says Dr. Bergenstal. “First, it will reduce the short-term complications of the disease, preventing the low blood sugar levels that are not only dangerous but also a big burden on people’s lives and schedules day-to-day. Second, the long-term studies of Type 1 diabetes overwhelmingly support the idea that good control—particularly early control that’s maintained—is really important. This system gives us a chance to reach the levels that we’re telling our patients we’d like to achieve.

“The third important impact is that it will reduce the burden of managing the disease,” he says. “Participants in the trial say it’s a big relief to let the system do some of the work so they don’t have to think about it every minute of the day. In particular, the participants and the parents of the teenagers we included in the study commented on the peace of mind the system allows them to have at night. Some of them told us that for the first time in a decade they could get a good night’s sleep because they had confidence that the system was going to work.”

Regarding insurance coverage, Dr. Bergenstal is optimistic. “Currently, most insurance companies are covering the sensor and the pump for Type 1 diabetes patients,” he says. “I’ve heard that the cost of the components will probably remain stable, so I think the insurance companies will look favorably upon the added safety that comes from combining the two technologies. Unfortunately, even if this is covered by insurance there will still be ongoing costs for the patient, such as the insulin and the infusion sets, as well as copays. On the other hand, it might reduce health-care costs by minimizing complications and keeping people out of the emergency room due to low blood sugar levels.”

Dr. Bergenstal points out that this is still an early stage in the development of a true artificial pancreas. “There will be many improvements to come,” he notes. “However, by and large, the study participants said this system was a great help to them.” In the meantime, the company is conducting trials to see if the system can be used by children between the ages of 7 and 14, and is gearing up to conduct long-term outcome studies. “Other companies are also working on this technology, so we’ll see competition,” Dr. Bergenstal says. “I think this is going to play a prominent role in the management of Type 1 diabetes over the next decade or so.”

To learn more about the MiniMed 670G, visit medtronicdiabetes.com on the Web. REVIEW

1. Bergenstal RM, Garg S, Weinzimer SA, Buckingham BA, et al. Safety of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA 2016;316:13:1407-1408. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11708.