Intraocular lens dislocation may be rare, but it’s a scenario every cataract surgeon prepares for. Late in-the-bag dislocation has been linked to pseudoexfoliation syndrome, uveitis, myopia and other diseases, and surgeons are trained in management strategies that include IOL exchange or suturing techniques.1 Not all cases are so easily explained, however. What if a patient presents with a late dislocated IOL and none of the typical conditions appear to be a contributing factor?

This could be “dead bag syndrome.” Coined over 25 years ago by Sam Masket, MD, this term refers to a capsular bag that appeared pristine and clear, with no posterior capsule opacification or fibrosis of the anterior capsulotomy. Despite its clean appearance, when it occurs late, this phenomenon often indicates a degenerating capsule bag.

Since its initial identification, reports of DBS are becoming more common, but its cause remains a mystery. We spoke with some of the surgeons who are at the forefront of the research and education around this syndrome to find out what progress has been made and what more needs to be done. Here’s what they said.

What the Research Says

|

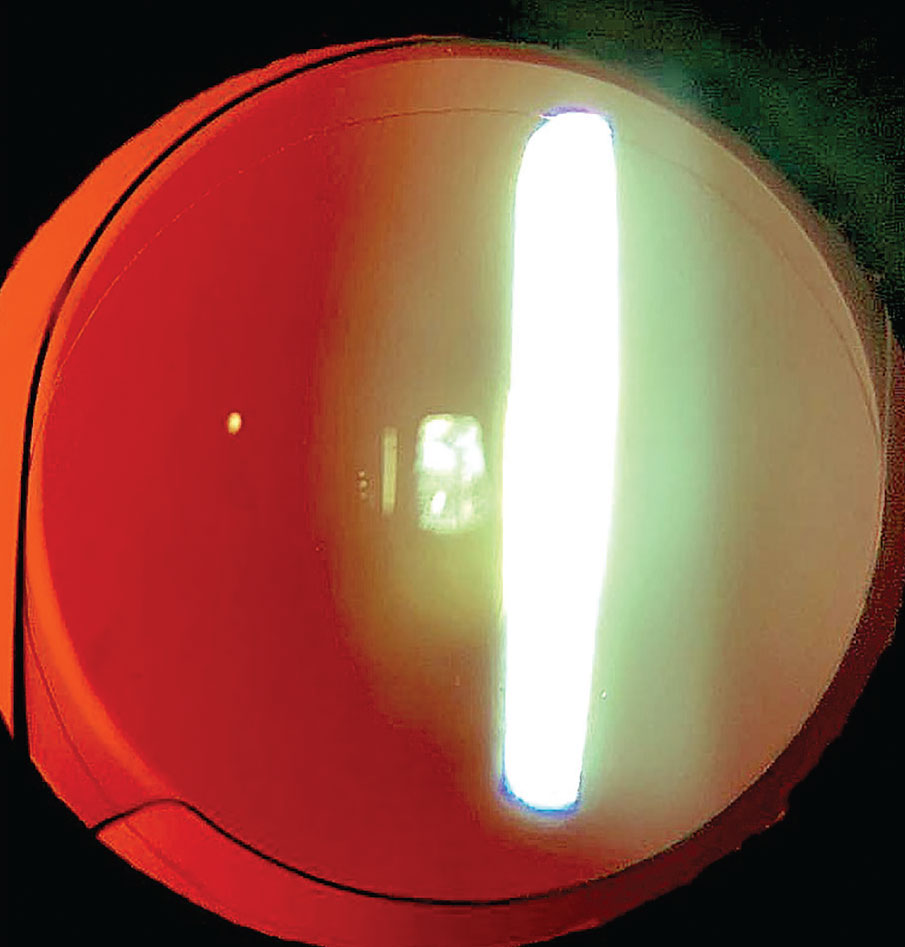

|

An in-the-bag decentration of this one-piece acrylic IOL is noted. Superior zonulysis is evident and the capsule is noted to be thin and clear with no fibrotic change; very minor PCO is noted. All images: Samuel Masket, MD |

Dr. Masket, clinical professor at UCLA’s Stein Eye Institute, was the first to sound the alarm on DBS after witnessing it in a couple of patients. He recalls attending meetings in the late ’90s and asking peers if they had observed this. It wasn’t until he got the attention of Liliana Werner, MD, PhD, and Nick Mamalis, MD, co-directors of the Intermountain Ocular Research Center at the Moran Eye Center in Utah, that real progress started happening on the pathology of these capsule bags.

Drs. Werner, Mamalis and Masket were co-authors, along with others, of a landmark study published in the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery in 2022.2 It included 10 suspected DBS cases, each of which had no signs of zonular instability during the cataract removal. Of those 10, researchers removed eight IOLs and seven capsular bags because of subluxation or dislocation. Histopathologic examination of the seven capsular bags showed capsular thinning and/or splitting. Two specimens were completely absent of lens epithelial cells, and five had rare LECs on the capsule’s inner surface.

“Their research revealed that lens epithelial cells in these bags had undergone degeneration and loss,” says Dr. Masket. “This raised the question of whether these cells were already deficient immediately following surgery, or if they had initially developed normally but then degenerated slowly over time.”

Dr. Werner explains, “Lens epithelial cells are important to the capsule as they continue to deposit extracellular matrix and lens capsule components at their basal ends, which contributes to the thickening of the capsule throughout life, as well as maintaining its integrity.

“On the other hand, the capsule is also important to the lens epithelial cells,” she continues. “It represents an anchor point for the basal surfaces of the cells, also providing necessary signals for proper lens cell proliferation, migration and differentiation. Therefore, in the dead bag syndrome there may be a problem in the cells, which degenerate, affecting the capsule, or a problem in the capsule itself, initiating a cycle of damage to the cells with further damages the capsule. The exact etiology is still unknown.”

In the cases included in the original JCRS paper, Dr. Werner says there were no fibrotic changes or proliferative material within the capsular bags. “The main histopathological findings were capsular splitting/delamination, and rare or absent lens epithelial cells attached to the capsule,” she says. “It’s possible that our cases represent the severe end of a spectrum, as informal online discussions describe cases where the capsule was floppy and delicate, but still exhibited a certain amount of proliferative material within it, including abnormal gel-like Soemmering’s ring formation.”

Research hasn’t slowed down. Just last month, Dr. Werner published another study, co-authored by Shizuya Saika, MD, and members of the Department of Ophthalmology at Japan’s Wakayama Medical University School of Medicine. This one focused on the immunohistochemical findings of DBS capsules.3

“Nine capsular bag specimens from dead bag syndrome cases, as well as two control specimens from late-postoperative in-the-bag IOL dislocation cases related to previous vitrectomy, pseudoexfoliation, and blunt trauma were included,” explains Dr. Werner. They were processed for histopathology; unstained sections were obtained from each one, and analyzed by immunohistochemistry targeting collagen type IV and laminin (components of basement membrane, i.e., lens capsule), vimentin (cytoskeletal components of lens epithelial cells), collagen type I and fibronectin (extracellular matrix components of fibrotic posterior capsule opacification).

“Immunohistochemistry confirmed that scarce or no lens epithelial cells were present in the capsular bags from dead bag syndrome cases, but suggested that cells were present after surgery, secreted components of fibrotic posterior capsule opacification, but something happened later and the cells died/detached,” she says.

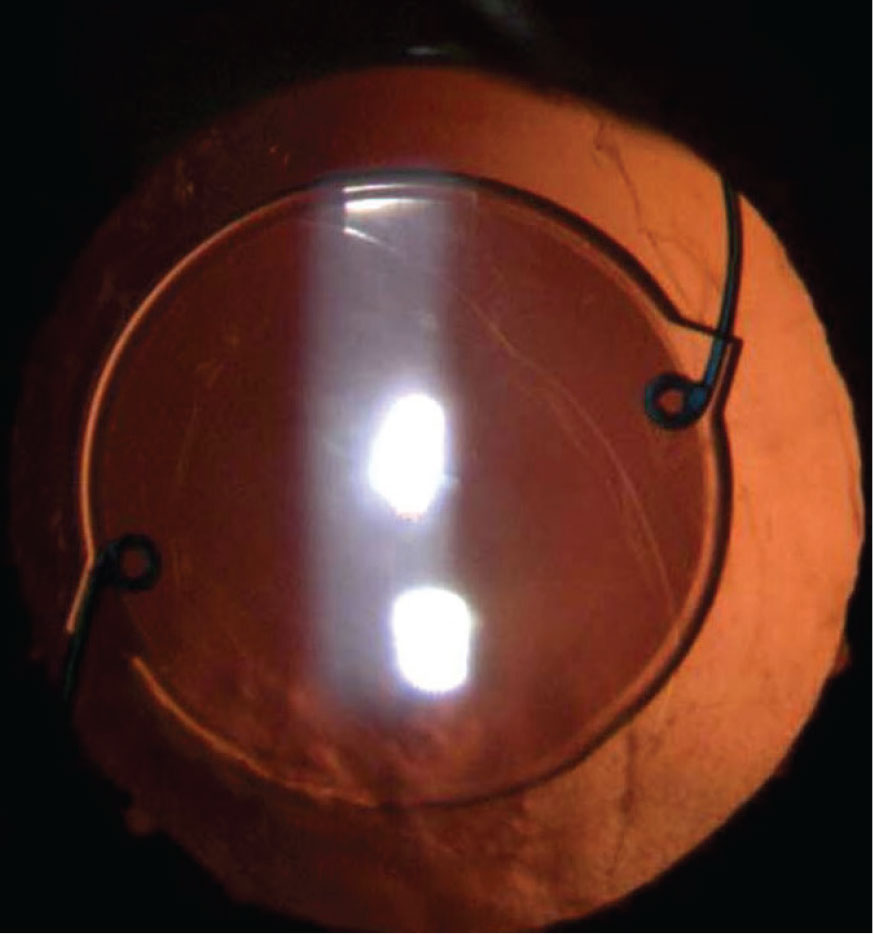

|

|

A perfectly clear capsule bag is noted in this eye now 11 years post routine cataract surgery. The anterior capsule rim shows no fibrosis and the posterior capsule is intact and clear. In this case there is no zonulopathy and the single-piece acrylic IOL is well centered. |

This research highlights the importance of distinguishing between different types of collagen laid down by lens epithelial cells post-surgery. “Dr. Werner determined that there was more fibrotic material present at one time, but that the type of collagen wasn’t characteristic of the normal postoperative capsule bag; it was a softer type,” Dr. Masket says. “There was also no evidence of vimentin. That would only be present if the LECs were viable. This indicates that the degeneration process doesn’t start immediately after surgery but occurs over time.”

Dr. Masket continues, “Histologically, the capsular bag is essentially the basement membrane of the lens epithelial cells, and as these cells degenerate, so does the capsular bag in some cases. This degeneration often affects the periphery of the capsule and the zonular fibers, which can lead to a decentered bag. In some cases, the entire capsular bag may become decentered, or the lens may decenter within the bag if it’s not fixated in a fibrotic fashion as it normally does postoperatively. If the capsule degenerates significantly, it can become thin and split, allowing the IOL to actually pop through the bag. Consequently, the lens may end up decentered within a decentered bag or even outside the bag.

“The variety of ways in which an IOL can become decentered from this condition is extensive, and we currently have more questions than answers,” he continues.

Thoughts on the Theories

Increased awareness of DBS has inevitably led to speculation on its causes within the cataract surgery space. Some can be debunked, while others need a closer look.

The first theory questions if DBS is related to capsular polishing during phacoemulsification. “When looking at the results of our original study, especially regarding the scarcity of lens epithelial cells in the capsules, surgeons are naturally asking the question about a possible relationship with capsular polishing,” Dr. Werner says. “There has been a lot of emphasis on polishing techniques to prevent capsular bag opacification, especially in association with premium lenses. However, even extensive polishing can’t completely remove all lens epithelial cells, and polishing is usually not done at the capsular bag equator, as this region isn’t readily visible. Therefore, to date there is no established association between capsular polishing and this condition.”

Dr. Masket also rules this out. “My first observed case of DBS didn’t involve phacoemulsification or capsule polishing,” he says. “This early case involved a white mature cataract treated with extracapsular cataract extraction, and yet the dead bag phenomenon still occurred over many years.”

Others wonder if the use of intracameral medications may be a cause. Again, Dr. Masket says this is unlikely. “Another case I performed in 1993, involving phacoemulsification under local block with no intracameral medications, also developed bilateral dead bag syndrome, eventually leading to a lens decentering and even UGH syndrome in one eye where one loop of the lens poked through the capsule,” he says.

|

|

Although LEC polishing and intracameral antibiotics have been suggested as possible causes of DBS, researchers haven’t found a connection. |

Self-induced trauma or eye rubbing is another theory. “There’s currently no pathological evidence linking eye rubbing to the changes seen in dead bag syndrome,” Dr. Masket says. “Eye rubbers are more prone to both cataract formation as well as zonulopathy, which is understandable from chronic trauma, but the evidence isn’t clear because most patients reported with dead bag syndrome have been monocular, which is inconsistent with the behavior of eye rubbers who typically rub both eyes.”

One link that is worth more investigation is that of atopic dermatitis. “An interesting development this year in the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery explored the capsular bag in patients with atopic dermatitis,” notes Dr. Masket. “The findings in these patients were quite similar to those observed in dead bag syndrome. This raises the question of whether there’s a link between atopic dermatitis and dead bag syndrome, a connection that has yet to be thoroughly investigated. The study distinguished capsular bag changes in atopic patients from those in patients with decentered or dislocated capsular bags due to other causes, such as pseudoexfoliation.”4

Finally, IOL type can be ruled out as a contributor, as DBS has been associated with all varieties of IOLs, including silicone, acrylic and PMMA lenses, and has been reported in both hydrophobic and hydrophilic acrylic lenses, says Dr. Masket.

Raising Awareness

There are many unanswered questions not only about the etiology of this syndrome, but also in its manifestations. Surgeons should be careful not to immediately presume any late, in-the-bag IOL dislocation is DBS. The condition itself remains rare, but those who are frequently referred to for dislocated IOLs may encounter a higher number, approximately one per month.

“The rate of late postoperative in-the-bag IOL dislocation has been reportedly increasing, and among the known predisposing conditions are pseudoexfoliation and other conditions associated with progressive zonular weakening,” says Dr. Werner. “However, in the dead bag syndrome, signs of zonular weakness are usually absent in the original IOL implantation procedure, and we hypothesize that late postoperative zonular failure is related to capsule splitting/delamination occurring at the level of zonular attachments. It’s therefore fitting that management is advised on a case-by-case basis, depending on presentation, as well as status of the zonular support.”

Dr. Masket says, despite the progress made on the topic, DBS is very much in its infancy. “Now that we’ve called the profession’s attention to it, my sense is we’re going to hear more from all the corners of the world,” he says. “DBS’s recent increased recognition parallels historical cases like hemorrhagic occlusive retinal vasculopathy. It was a postoperative complication with horrific retinal changes that turned out to be associated with an unusual immunologic response to intraocular vancomycin. There weren’t a large number of cases, but all of a sudden cases started coming out of the woodwork. Many of us had used intraocular vancomycin for years and never saw a case, but awareness eventually led to understanding and resolution.

“I think we’re going to see a parallel here with DBS,” he concludes. “As the profession becomes more alert to this phenomenon, further reporting and research will be essential to uncovering its causes and improving patient management.”

1. Gimbel HV, Condon GP, Kohnen T, Olson RJ, Halkiadakis I. Late in-the-bag intraocular lens dislocation: Incidence, prevention, and management. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31:11:2193-204.

2. Culp C, Qu P, Jones J, Fram N, Ogawa G, Masket S, Mamalis N, Werner L. Clinical and histopathological findings in the dead bag syndrome. J Cataract Refract Surg 2022:1:48:2:177-184.

3. Sumioka T, Werner L, Yasuda S, Okada Y, Mamalis N, Ishikawa N, Saika S. Immunohistochemical findings of lens capsules obtained from patients with dead bag syndrome. J Cataract Refract Surg 2024;1:50:8:862-867.

4. Komatsu K, Masuda Y, Iwauchi A, Kubota H, Iida M, Ichihara K, Iwamoto M, Kawai K, Yamamoto N, Shimoda M, Nakano T. Lens capsule pathological characteristics in cases of intraocular lens dislocation with atopic dermatitis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2024;1:50:6:611-617.