As we move into the digital era, a host of new technologies (and the problems and advantages that accompany them) continue to appear. As part of this unfolding story, the evolution of electronic health records has led to the possibility of collecting and analyzing enormous amounts of data—and as people have begun exploring this possibility, large databases of information have begun to spring up.

Here, people with extensive experience with two of the current databases in the United States—the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s IRIS (Intelligent Research In Sight) Registry, and the Vestrum database, currently working exclusively with retina specialists—share their experience, discuss the pros and cons of these systems, and offer their thoughts on where this technology may lead us in the future.

The IRIS Registry

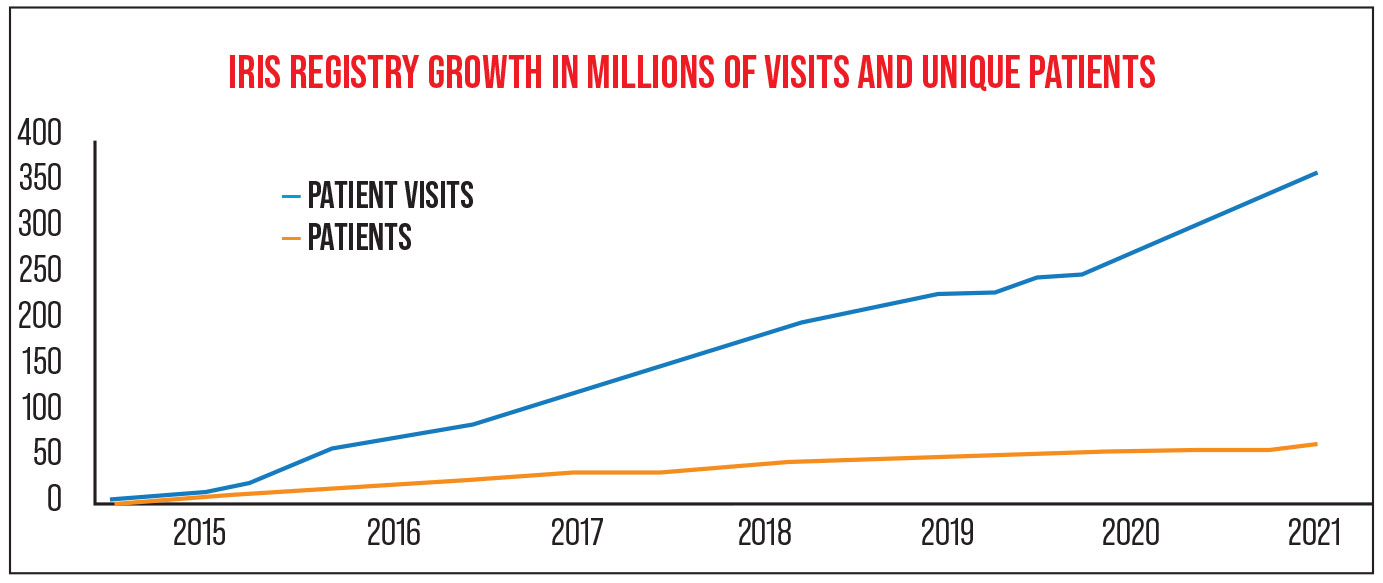

“The IRIS Registry started in 2013,” notes Flora Lum, MD, vice president of Quality and Data Science for the AAO since 2015. (She leads the Academy’s quality of care programs and the teams that are responsible for clinical guidance, public health and data analytics initiatives, including the Academy’s IRIS Registry.) “As of April 1st 2021, about 3,000 practices are contributing their EHR data to the database; we have data on 68 million unique patients and 387 million visits. The majority of practices in the United States are participating, and we believe our data includes the majority of eye-care patients in the U.S.” (Participating in the Registry is free to members of the Academy.)

The Academy has partnered with other companies to help manage the massive amount of data the IRIS Registry brings in, as well as potential commercial applications for that data. Currently, the Academy is working with Verana Health, a company with offices in San Francisco, New York City and Knoxville, Tenn.

|

Mark S. Blumenkranz, MD, MMS, H.J. Smead Professor of Ophthalmology, Emeritus, at Stanford University, CEO of Kedalion Therapeutics and a director of Verana Health, explains that Verana helps to manage the enormous amount of data collected by the registry, in a number of ways. “Data collection is a complex operation,” he says. “Even though most of the relevant data now resides within EHRs rather than paper records, it’s not as simple as just pulling it out and sticking it into a computer algorithm for compilation and analysis. Data needs to be curated to be certain it’s accurate and reproducible.

“For instance, sometimes data entered into an EHR is misclassified,” he explains. “You have to have mechanisms by which you can ensure that the data being extracted is of good quality—that the fields were filled out properly. If you don’t curate the data, it’s essentially worthless, or at least of limited value. But data curation takes time, and it’s expensive.

“How quickly the data is processed is also an issue,” he continues. “For example, if you’re looking at trends in drug treatment and you identify a potential problem with a drug, you need to get the data right away. You need to have automated extraction routines and connections between the servers and the data repositories.”

Users in the field report a positive experience with the IRIS Registry. “We started using the IRIS registry when they first created it,” says Michele Huskins, EHR specialist at the Rocky Mountain Eye Center in Pueblo, Colorado, a practice currently employing 21 ophthalmologists and optometrists. “For us, it’s been great. I think the reporting is much better than what I can get from my EHR. For example, I can pull up reports listing patients who do or don’t meet a given measure. I can also open tickets and go back and forth with staff members.”

Ms. Huskins says that being part of the registry is very easy. “It takes all of the data right out of our database,” she notes. “I just look at the dashboard, which they update once a month, and pull reports on the things I’m concerned about. It’s very user-friendly.

“What’s really nice is that the system will map custom fields like those we’ve created in our EHR system, to give us the data we need,” she continues. “They take screen shots of our templates. For example, we have custom templates for patients who are converting to cataract surgery, and we’ve created some custom fields like the surgeon’s planned refraction. We’re currently working with the IRIS registry folks to map those fields, so whatever our doctors put in about how close the patient came to the planned refraction, they can pull up later as part of a report.

“The registry folks also make sure the database is capturing the pre-existing fields in which we enter information we need,” she continues. “In contrast, sometimes the EHR’s workflows are not very user-friendly—we have to do a lot of clicking to get to the data we need.”

|

|

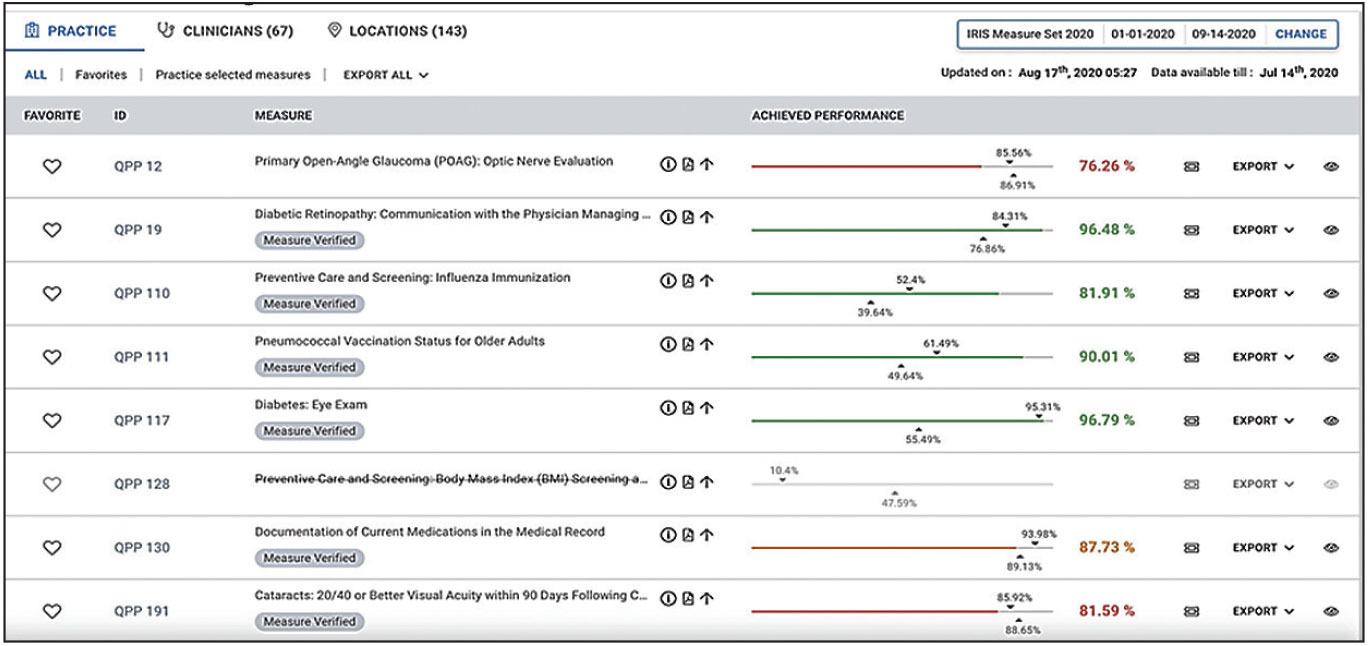

A sample IRIS Registry dashboard relating to practice quality measures. (© FIGmd Inc 2021. All rights reserved. No reproduction in any form without prior permission from FIGmd.) Click image to enlarge. |

One of the most popular—and practical—ways in which the IRIS Registry helps practices is by generating the reports that practices are required to submit to comply with Medicare quality-of-care standards. “Over the past five years,” Dr. Lum says, “our quality reporting has helped practices avoid more than $1 billion in penalties relating to Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System [MIPS], as well as helped practices achieve small bonuses every year.”

“Creating those reports is a big burden to physicians,” Dr. Blumenkranz points out. “It takes a significant number of people and amount of technical expertise to generate them. The partnership between the AAO and Verana is sort of a perfect synergy in this respect.”

Vestrum Health

Another data registry in the United States is Vestrum Health, which currently works only with retina specialists; it was also started in 2013. “The Vestrum database is able to acquire HIPAA-compliant, de-identified data directly from a practice’s EHR, without any effort from the physicians themselves,” explains David F. Williams, MD, MBA, a partner at VitreoRetinal Surgery in Minneapolis/St. Paul, and cofounder of Vestrum Health. “We specify the data fields that are valuable—the ones that can provide actionable data—and then we aggregate the data from each practice into an analyzable database. The database contains all of the historical data for the practice, and it’s updated on a weekly basis; it can be queried and analyzed to answer almost any clinical question a doctor may have.

“We’re currently working with about 15 to 20 percent of the retina specialists in the United States,” he says. “That’s a meaningful percentage because the practices participating are representative of retina as a whole, in terms of their geographic distribution, size and other characteristics. People don’t pay to participate; Vestrum provides data and analysis that’s valuable to practices in exchange for access to the EHR data from them. We’ve also done projects for industry.

“With today’s EHR systems, it’s very complex—or even impossible—for a practice to try to pull data out in any organized, analyzable fashion,” he continues. “But with Vestrum, if participants want to do a research project or look at some aspect of their own practice, they just have to let us know and we can do it with them.”

Dr. Williams says Vestrum provides participating practices with a standardized monthly report called QuickTrends, showing the practice’s data. “It’s secure, de-identified and HIPAA compliant,” he notes. “It allows you to analyze different aspects of your practice—the volume of different procedures, outcome trends, realizations of drug treatments, and so forth. Vestrum is now developing a version of the report that includes a searchable database containing all of the practice’s EHR data over time.”

Dr. Williams says that Vestrum’s relatively small size is both an advantage and a disadvantage. “The feedback we get is that the Vestrum system is very user-friendly, partly because of our smaller size,” he notes. “It’s easy to make changes on the fly, and easy to get in touch with the people providing data to you. That makes it easy to adjust the data you’re seeing, refine the questions you’re asking and drill down to the answers you’re really looking for.”

Dr. Williams admits, however, that Vestrum’s size is also something of a disadvantage. “We’d like to grow the panel of physicians who contribute to our database, in part because we don’t have the same power that a large organization like the American Academy of Ophthalmology has,” he says. “We can’t compel the EHR databases to provide their data to us for free, so we pay the EHR providers to make the connections for us. We ask our practices to encourage their EHR provider to not only provide the data but provide access to more data fields so that we can do even more nuanced investigations.”

Practice Benchmarking

There’s no question that practices can benefit from being able to do both external comparisons—how the practice is doing compared to other similar practices—and internal comparisons, revealing how different branches of a practice, or individual doctors, are doing compared to the others.

“We provide two types of benchmarks, one based on data from CMS for all reporting through MIPS, and one based on everybody who reported to us,” explains Dr. Lum. “We report the data for the ophthalmologists in the registry, and data for optometrists and other clinicians, depending on the type of measure in question. So a practice can see how it’s doing overall, and how it’s doing within the IRIS Registry.

“In addition, doctors can look within their own practice and compare different staff members and different office locations,” she continues. “They might find a noticeable difference between two locations; if so, they can try to figure out why the workflow or documentation is different here than there. In essence, the data allows them to look at the quality they’re delivering and helps them manage it.”

Dr. Lum notes that doctors can drill down to individual patient data. “We like to give what we call ‘actionable feedback,’ ” she says. “Saying that 20 percent of your patients didn’t meet a measure doesn’t help you much. With this data you not only can see that one particular patient didn’t meet the measure, you can also go back into your EHR system and see if the surgeon didn’t document something, or whatever else the explanation might be.

“A practice can make adjustments to its workflow, or call patients to get them to come back, or send a report to the referring specialist,” she continues. “It all depends on which measure they’re looking at. Practices can screen for different patient characteristics, such as use of tobacco or comorbidities, and use that data to evaluate their patient population and risk factors. You can look at all of your glaucoma patients and see how they’re doing with IOP control, or look at your diabetic patients and see how many have had a letter sent to their primary care physician. It’s a very extensive and detailed program.”

Dr. Lum notes that access to this data is also timely. “Normally, when you report for MIPS, you don’t get your performance and follow-up data until about a year and a half later,” she points out. “In the IRIS Registry, every practice has a dashboard that’s refreshed with new data every month.”

Ms. Huskins says her practice takes advantage of the benchmarking capabilities. “I compare our practice to the rest of the country,” she says. “For about half of the measures, we’re above the national average. I look at reports showing patients who are not meeting a measure, and then look for the reason. That helps us know what we need to improve on. It’s definitely giving us information that we can use.

“I also do a little bit of comparing within the practice, doctor to doctor,” she adds. “Often that alerts me to a mistake in our data capture; if one doctor’s numbers are very low, I know it’s an issue with our data capture and I can do something about it.”

Ms. Huskins says this kind of data analysis has led to practical changes. “For example, each day I automatically create a report in our EHR that shows me all the people who came in yesterday with a diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy,” she says. “Then, I check each patient’s chart to make sure that we’ve sent a letter to the primary care physician. If not, I send a note to the tech to take care of that. Later, if the diagnosis says that the patient no longer has retinopathy, I send the tech a task to remove that from the patient’s chart, so the patient is no longer part of the denominator for that measure. Without the IRIS system, we couldn’t manage this as easily.”

Dr. Williams says having access to Vestrum in his own practice has made a significant difference. “It gives us an awareness of what’s happening on a larger scale, rather than just basing our judgments our own day-to-day experience with patients,” he notes. “For example, it’s allowed us to look at some of our outcomes using different drugs. Because of what the data has revealed, we’ve made some mid-course corrections in practice activities. Being able to quickly look at trends in our patient numbers, treatment numbers and utilization of various pharma products—without having to query someone in our business office—has been very helpful.”

Assessing Real-world Impact

Another key use for large databases of real-world information is monitoring what actually happens when a drug, device or even a new technique comes into common use.

“After a device or drug gets approval, you still have to commit to doing research to see what happens in the real world,” says Dr. Lum. “We have a natural surveillance system that can detect adverse events, such as adverse ocular effects arising from a systemic drug. Doctors and practices are too busy, or simply forget to file formal adverse effect reports, even though those systems are in place. Our data can help companies and the FDA look at early warning signs of any issues that come up. With so many patients in the database, we can spot them before anyone else is likely to.”

Will Big Data Replace Clinical Trials? Given that a large database can show real-world outcomes of different treatments, it’s reasonable to wonder how this might affect the conduct of clinical trials in the future. Recently, Verana Health was able to use real-world data from the IRIS Registry to replicate the primary outcome measures of the VIEW I and VIEW II clinical trials. (Those trials led to the 2011 U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of aflibercept [Eylea, Regeneron] for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration.) In this registry-based retrospective study, the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the VIEW studies were applied to patients whose data were part of the IRIS Registry; 4,779 patients were found whose disease and treatment were comparable to the 1,632 subjects in the trials. Matching the treatment times, the proportion of eyes losing fewer than 15 letters among the IRIS Registry patients was similar to that found in the VIEW studies, indicating proof-of-concept. This was the first time a real-world dataset was able to replicate the results of a large randomized, controlled clinical trial. “This type of data differs from the data produced by prospective, randomized clinical trials in some fundamental ways,” notes Mark S. Blumenkranz, MD, MMS, H.J. Smead Professor of Ophthalmology, Emeritus, at Stanford University, and a director at Verana Health. “The clinical trial data can provide a lot of insight into whether a drug is effective or not. But how these drugs end up being used in the real world is a huge concern. Maybe the frequency of drug administration is different; maybe the dosing is different. The real-world data gives us a much better idea of how the drug functions in real-time clinical practice.” “Unfortunately, using the database in this way doesn’t always work because the patient characteristics may be hard to duplicate,” notes Flora Lum, MD, Vice President of Quality and Data Science for the AAO, who works with the IRIS Registry. “We tried to do this to confirm the results of one small glaucoma study, and we weren’t able to replicate the clinical trial results. We couldn’t find patients that neatly fit the categories used in the randomized, controlled trial, and some of the technology and practice patterns had changed since the study was done. But in the more recent attempt [described above], we were able to replicate the patients in the study more successfully.” Dr. Lum says she doesn’t believe a large database like the IRIS Registry will ever allow researchers to skip doing clinical trials. “The registry provides observational data,” she notes. “We can’t provide strict controls and we can’t prove causality. It might be possible to use the IRIS Registry as a mechanism to collect the data for a randomized, controlled trial, but real-world evidence isn’t the same as randomized, controlled trial data, which is level-one evidence because of its strict protocols and controls. “On the other hand, we can use the IRIS Registry to see if what happened in a randomized controlled trial actually does work in the real world,” she continues. “The database could be an adjunct that can help to reinforce what we learn and then also raise questions. It might reveal, for instance, that because of trends or changes in practice patterns, a given study’s results may no longer apply in the real world.” —CK |

Dr. Blumenkranz agrees. “One key thing this data can do is provide information about what’s currently happening, such as timely estimation of the incidence of different diseases, and how good the results of specific treatments are,” he says. “The data coming out of the IRIS registry, once it’s been curated and analyzed, provides real-world evidence for assessing the safety and efficacy of any number of different types of interventions: drugs; devices; public health measures; and so forth.”

For example, a 2020 study used the IRIS data to compare the effectiveness of treatments for 13,410 treatment-naïve patients newly diagnosed with diabetic macular edema who were seen between July 2013 and March 2016.1 It found that:

— 74.5 percent of patients received no treatment within 28 days of diagnosis.

— Within the first year, 3,155 (24 percent) were treated with anti-VEGF injections; 1,841 (14 percent) received laser; 239 (1.8 percent) were treated with steroids; and 81 (0.6 percent) received a combination of two or more treatments.

— Among patients receiving anti-VEGF injections, 71.3 percent were treated with bevacizumab, 17.1 percent with aflibercept, and 11.6 percent with ranibizumab.

— Patients who were treated within the month following diagnosis had greater initial visual impairment than those not treated during month one, and achieved greater levels of visual acuity improvement at one year.

Dr. Blumenkranz notes that this kind of data can also reveal rare side effects only evident when large number of patients are exposed to a treatment. “In fact, there was at least one recent drug introduction where a very infrequent but very serious complication was identified subsequent to approval,” he says. Dr. Williams says Vestrum’s data has also shown that real-world outcomes can diverge from the outcomes in pivotal clinical trials, including in the trials that led to the approvals of different anti-VEGF agents currently in use.

This type of real-world monitoring can also be used to assess the value of a new surgical technique, or to compare the outcomes of different surgical options. “Doctors often have questions about whether one technique produces better results than another,” Dr. Blumenkranz notes. “In most cases, no one is going to conduct a clinical trial to resolve this; most of the time you can’t do a large enough trial, for ethical and practical reasons, to be adequately powered to get an answer. Even when people have tried, the results have often been inconclusive.

“On the other hand, if you look at the data from more than 1,000 retinal surgeons, you’ll see that some do things one way, some do things another way,” he continues. “Based on their outcomes, even though you’re not randomizing, the numbers are large enough that you should be able to derive some degree of statistical significance around the differences in outcomes using retrospective data, if appropriate methods of matching are employed. It’s essentially an alternative to a prospective, randomized clinical trial.

“The conclusions aren’t as indisputable,” he admits, “because you can’t ensure that the patients in one group are identical to the others; but if you start with very large numbers, you can create pretty comparable groups in terms of their baseline characteristics. From that you can work backwards to conduct a sort of synthetic trial, where you have patients randomized to multiple groups post-hoc.”

The data has also been used to demonstrate how potential changes could improve things like systemic health-care costs. A study published in 2020 used data from the IRIS Registry, together with Medicare claims data, to demonstrate that a 10-percent increase in bevacizumab market share relative to ranibizumab and aflibercept would result in Medicare savings of $468 million and patient savings of $199 million. This could be triggered by increasing the reimbursement for bevacizumab to equal the reimbursement for aflibercept, eliminating the financial disincentive responsible for the limited use of bevacizumab.2

Moving Ophthalmology Forward

Being able to access great quantities of real-world data is also having an impact on the field as a whole, via a number of data uses:

• Providing data for research reports. “Verana Health is helping to create the research reports that are being published by the Academy, using the IRIS database to detect trends and answer questions,” says Dr. Blumenthal. “The partnership enables the data to be of very high quality, including providing statistical support.”

For example, a study of endophthalmitis occurring within 30 days of cataract surgery in the United States, based on IRIS Registry data for 8,542,838 eyes that underwent the surgery between 2013 and 2017, was published in 2020.3 Among other things, the data revealed that: 3,629 eyes developed endophthalmitis (0.04 percent); the incidence was highest among patients 17 years of age and younger (0.37 percent over five years); endophthalmitis occurred four times as often following combination surgeries, compared to standalone surgery; and 44 percent of patients who developed endophthalmitis still achieved 20/40 or better visual acuity at three months.

• Helping to guide researchers working on developing new drugs. “When you’re trying to develop new drugs, one issue is deciding which diseases to treat,” Dr. Blumenkranz points out. “With registry data, you can find out the number of patients with a given health problem who are being seen, whether they’re being treated, and what the clinical outcomes are. Based on that, you can come up with a list of the most common diseases and which ones we have good treatments for. Then you can tailor your drug discovery process to diseases that are frequent but have limited treatment options.”

• Recruiting patients for trials of rare disease treatments. “If a disease is encountered infrequently, as with orphan diseases, the number of affected patients can be small and clinical trial recruitment can be challenging,” Dr. Blumenkranz notes. “No single center will have a large number of those patients that you can quickly enroll. The registry data gives you an overview of the large-scale epidemiology.

“Another way Vestrum is helping practices is by enhancing their recruitment into current clinical trials,” says Dr. Williams. “If a practice wants to avail itself of our clinical trial service, we can look at the eligibility criteria for a particular trial and then search the practice’s database and generate a list of patients that might meet the trial’s eligibility criteria. We can include patients that might have been seen even years ago. That’s a list the practice itself might have a hard time compiling.”

Dr. Lum also notes that the IRIS Registry might allow data to be collected for a clinical trial more easily. “If you can enroll patients from participating practices and then use the IRIS Registry to collect data,” she says, “you could probably do a trial for less money, and quicker.”

Adding Images to the Database

Something that all current databases are investigating is finding ways to include images in the database. “The optimal database should contain three things: the traditional EHR data, e.g., symptoms, signs, physical findings, and lab tests; medical imaging, which is particularly important in ophthalmology; and genomic data,” says Dr. Blumenkranz. “If you have those three components, you have a pretty complete understanding of the patient.

“For example,” he continues, “if you see somebody who has a complement-factor-H abnormality and also has a few drusen, you know that patient is at risk for vision loss. If you just saw that patient in the clinic and their vision was 20/20, you wouldn’t necessarily have gotten a sense of the likelihood of that patient going on to more severe vision loss, or the optimal frequency of follow-up exams. Having the retinal image and genotype can be crucial.

“It’s possible for the IRIS Registry and Verana Health to incorporate all three of these types of information,” he notes. “Part of it is just a logistics issue; we have to get patient permission, practice permissions, determine who owns the data, and so forth. But it’s not a particularly big deal to integrate those three things. However, getting the image data is currently a challenge due to issues of compatibility between different storage systems, as well as concerns about data ownership and privacy. Some EHR vendors are starting to incorporate images, but many practices use a separate vendor to provide storage for images.”

Not surprisingly, analyzing the images to make them meaningful as data is an issue. “Up until now it’s been extraordinarily labor-intensive to analyze imaging data,” Dr. Blumenkranz says. “At reading centers people sit at a desk with a magnifier, and it’s hard work. But an AI-enabled software package can analyze an image in milliseconds. So I think the ability to handle all of that data will become increasingly easy because of automated data ingestion and image analysis. Of course, people will have to decide the purpose of the analysis, and the software has to undergo training and validation and approval. But once that’s done, the task will be dramatically easier and faster for a machine than for a person.”

Dr. Blumenkranz points out that there are also security issues that may arise connected to including images in the database. “We’ll need to have adequate protections for privacy,” he says. “A fundus image is both protected health information and personal, identifiable information. A computer algorithm can tell from a fundus photo who you are—if the algorithm can match the photo to another image that’s out there. It’s like the debate over whether facial recognition software should be used on the street. Some of the same questions apply to medical images. It’s not an issue right now—but it could be in the near future.”

“Being able to correlate what’s showing up in the EHR with the image findings is the Holy Grail for a lot of research studies, and also for industry,” says Dr. Williams. “However, I’m not sure anybody’s been able to solve the practical problems at this point. Vestrum has been working on it for a while, and we know that we can do it. It’s just going to require some significant resources and the commitment of practices that also want to get involved in this type of project.”

Into the Future

Dr. Lum believes a database like the IRIS Registry will allow doctors to improve treatment. “Doctors have never had a tool that could let them look at all of their diabetic patients, for example, or all of their cataract patients,” she says. “The findings of IRIS Registry analytics should help doctors make decisions about what treatments are best for which patients. And it can help clinicians understand disparities in care by revealing which patients get treatment and which don’t, or why some patients are lost to follow-up. The data may also help to understand more quickly new treatments that are working well, which might help accelerate payer acceptance of those treatments in clinical practice.”

In terms of the future, Dr. Lum sees the database helping to answer questions about when, and in which patients, a given treatment is likely to be effective. “Big data in concert with artificial intelligence could help doctors treat and diagnose better, because we have all of those data points,” she notes. “But that’s farther in the future. In the meantime, our trajectory is to try to incorporate clinical images, because they’re used so much in diagnosis and treatment. They give us a more complete picture of patients and their disease status and severity. That’s what we’re working toward.”

Dr. Williams says Vestrum Health is working on incorporating practice management and billing data into the system, and then correlating that with data from the EHR. “We have the ability to provide practices with billing data statistics and compare it to their peers around the country, as well,” he explains. “We’re working with companies that have claims databases, to merge our granular and nuanced EHR data with that information. That will allow us to do an even more sophisticated analysis of the delivery of health care in retina.”

Dr. Williams believes the future of big data is very promising. “Ideally, you need to have a well-organized, representative database that includes all of the EHR data fields—including the text fields—that contain useful data,” he says. “And you have to have good people, and possibly AI, to analyze the data. But I think in the long run, big data in health care is going to have tremendous value. It’s a matter of us identifying and accessing that value.”

Dr. Blumenkranz is a director at Verana Health. Dr. Williams is a cofounder of Vestrum Health. Dr. Lum is Vice President of Quality and Data Science for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ms. Huskins report no financial ties to any product discussed in the article.

1. Cantrell RA, Lum F, Chia Y, et al. Treatment patterns for diabetic macular edema: An Intelligent Research in Sight (IRIS) Registry analysis. Ophthalmology 2020;127:3:427-29.

2. Glasser DB, Parikh R, Lum F, et al. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor cost savings achievable with increased bevacizumab reimbursement and use. Ophthalmology 2020;127:12:1688-1692.

3. Pershing S, Lum F, Hsu S, et al. Endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in the United States: A report from the Intelligent Research in Sight Registry, 2013-2017. Ophthalmology 2020;127:2:151-158.