Who's Getting the Surgery

In recent months, surgeons have presented the results of refractive surgery in these unusual patients.

Minneapolis surgeon David Hardten performed a retrospective study of 79 wavefront-guided PRK patients with unusual aberrations and inferior steepening that, in his estimation, some surgeons would exclude from having LASIK refractive surgery.

"We arbitrarily picked [as criteria] those with over 0.15 µm of coma or trefoil greater than 0.15 µm. This is a fair amount of coma," Dr. Hardten explains. "The average spherical equivalent in our group of eyes is -2.5 D, and the average astigmatism is higher than the general population at 0.76 D. Their spectacle prescription didn't change a significant amount in the year before surgery. These are not patients who are rapidly changing.

"Of the 79 eyes, 96 percent with at least a month of follow-up have 20/40 or better uncorrected vision, and 73 percent see 20/25 or better. The results aren't as good as a population of patients with totally normal eyes, but they're very good for patients with this level of irregular astigmatism.

"We put these patients in a group called 'significant levels of coma and trefoil' partly because those two criteria are some of the characteristics you'd get with keratoconus suspects, though these are much milder than what most would call keratoconus." He says that, though many of the patients have been stable over six months with no cases of ectasia or very unusual results, it usually takes six months to a year for vision to improve with PRK.

Before performing the procedure on these patients, Dr. Hardten says he emphasizes to them that they might be at higher risk for developing keratoconus. "I stress to these patients that if they have this problem, and it gets worse over time, then they may not have a stable outcome from their refractive surgery," he says.

As to who wouldn't be a good candidate, Dr. Hardten says there's no definite dividing line. "It's hard to draw a line that says when something's normal or a little abnormal," he says. "It's sort of like defining a 'normal' person. In general, if the cornea's relatively thin, the patient has a relatively high correction and there's a relatively high amount of asymmetry, I may not want to take off that much tissue, and might lean toward an initial procedure like combined conductive keratoplasty and Intacs. That might get them enough improvement for them to go on to PRK later, with the need for less tissue removal and asymmetrical ablation because they've had the Intacs and CK."

Boston surgeon Helen Wu retrospectively studied the results of standard surface ablation in patients who were considered at risk for ectasia if they were to undergo LASIK, due to such factors as evidence of forme fruste, or hidden keratoconus and thin central corneal thicknesses. The surgeries were performed over a seven-year period from 1998 to 2005. According to her presentation at the Hawaiian Eye Meeting, Dr. Wu didn't find any cases of ectasia, and she says PRK in these patients appears to have been effective, predictable, stable and safe thus far.

Miami surgeon Bill Trattler agrees there can be problems when LASIK or PRK are performed on patients with keratoconus by weakening the cornea through excessive thinning. "The steepest part is also the thinnest part, so the last thing you want to do is give extra treatment to the steepest part," he says. "So, unfortunately, PRK really isn't the best option for patients with frank keratoconus."

However, he has performed surface ablation on around 30 eyes with what he terms "mild forme fruste keratoconus," which he describes as a situation "where you might have a thick cornea, but there may be some change that makes you suspicious, such as some inferior steepening, but the patient is still correctable to 20/20." He thinks PRK is an option in these patients as long as they're made aware through a more involved informed consent process that they're at risk for developing keratoconus in the future.

"In my limited experience, these patients have done well so far," Dr. Trattler says. "These patients' outcomes seem to be less accurate than others, and more of them require enhancements than non-forme fruste patients. I haven't had any patients in this group develop keratoconus yet, but that doesn't mean they're not at risk for problems down the road." These patients have up to three years of follow-up.

|

|

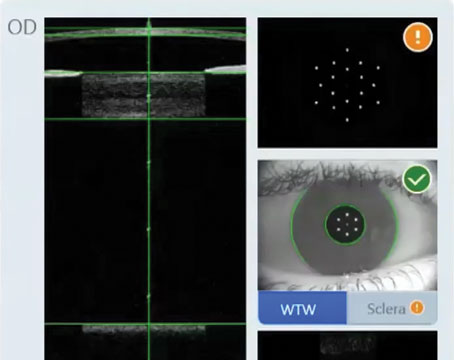

| A -5.12 D patient with 0.23µm of coma (left), which can occur in keratoconus suspects. The eye had acceptable PRK result (right). David Hardten, MD |

The Skeptical View

Naturally, the thought of performing refractive surgery on a patient who even resembles a keratoconus suspect is met with skepticism by some surgeons.

"I personally would never perform a subtractive procedure on a patient who I felt had either keratoconus or forme fruste keratoconus," says Chicago surgeon Randy Epstein, MD. "Both laser procedures and any kind of incisional procedure will result in a weakening or loss of tissue in a cornea that we already know is structurally weak …. The whole problem with keratoconus is that it's a moving target and you don't know when it's finished. Many people will talk about getting great results doing this or that, but they may have a different take on things 10 years later."

Parag Majmudar, MD, Dr. Epstein's partner, also takes a conservative view on such procedures. "When we evaluate patients, we look at a number of different things," says Dr. Majmudar. "And I rely on Orbscan pretty heavily. If there's any type of frank or forme fruste keratoconus, I avoid doing any refractive surgery, just from a medico-legal standpoint. A lot of these people will progress whether you do surgery or not. My feeling is that there's no way you will be able to support your belief that your surgery didn't make it worse .... No matter how much you tell patients that 'you may get worse after we do the laser but it's not the laser's fault,' eventually they'll find their way into the legal system."

"I respect the decision of some surgeons not to operate on these types of patients," says Dr. Hardten. "But I think we have a very hard time predicting the future and the responses to our current actions, and most of these patients probably don't really have keratoconus and aren't going to progress over time, though some do. However, there certainly is some retrospective evidence that there are patients with keratoconus now who, when you look back five years to when they had a procedure done, might have had a little bit of inferior steepening.

"We don't really know the exact incidence of ectasia after refractive surgery, or the link between them," he adds. "We know that many patients with ectasia had abnormal topographies before their LASIK or PRK, but that's different from saying that if you take 100 patients and operate on them, you know what will happen in a year, two, five or 10 years. Some patients will develop keratoconus even without laser refractive surgery."

Dr. Trattler also thinks that, with extensive information, a patient with what he deems mild forme fruste keratoconus can at least know refractive surgery is an option. "It's not something we want to push," he says. "But we can say to certain patients, 'Listen, these are the issues and you may want to consider it, or you may not.' That's the patient's prerogative."