A SMILE Refresher

Since SMILE is relatively new on the refractive scene in the United States, it might be helpful to describe the procedure.

What makes SMILE unique is that it’s an all-femtosecond laser refractive procedure. The only laser currently able and approved to perform SMILE is the VisuMax femtosecond laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec). The surgeon uses the laser to cut a lenticule-shaped disc of tissue within the cornea and then create a side cut through which this lenticule is removed. The removal of the lenticule is what causes the change in refraction.

In the United States, SMILE is approved for the treatment of -1 D to -8 D of myopia, with no more than -0.50 D of astigmatism and a manifest refraction spherical equivalent of -8.25 D, which has been stable for a year.

Preop Screening and Exam

When evaluating SMILE candidates, the selection criteria are similar to those used for LASIK.

I exclude patients with suspicious corneal topography or thinner-than-average corneas. I know that some SMILE surgeons feel SMILE has better biomechanical stability than LASIK, and there have been some studies to that effect, but I still strive to maintain a minimum preop corneal thickness of 500 µm. Some surgeons think SMILE will expand the number of patients you can treat by including those with corneas that would be risky for LASIK, but I disagree. I think the indications will be virtually identical to LASIK’s. Since you sever fewer corneal nerves, however, I believe that patients experience less dry eye with SMILE than LASIK, and papers have borne this out.1,2

When selecting candidates, we’re somewhat limited in the United States in that we can only treat between -1 and -8 D. The machine will, however, allow you to treat up to -10 D, though you’ll get a yellow warning light indicating that the treatment is above the approved range and that there’s not enough information on treatments above that range. Internationally, however, SMILE has been shown to work very well in myopia above -8 D. The other aspect of the treatment ranges you’ll notice is that you can’t program any astigmatism correction into the treatment, at least in the United States. This makes patient selection a bit more challenging because, typically, many patients will have some degree of myopia and astigmatism. For instance, one eye might have 0.25 or 0.5 D of astigmatism, while the other has 0.75 D. This limits the pool of patients who can undergo SMILE surgery at this time.

In addition to the cornea and refractive aspects, we also look for other signs of ocular health. In other words, there should be no corneal staining, no epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and no external eye disease like blepharitis. If there’s meibomian gland dysfunction, we’ll also treat that preop.

The preop discussion with the patient needs to be handled a certain way. Some patients, having heard about SMILE

|

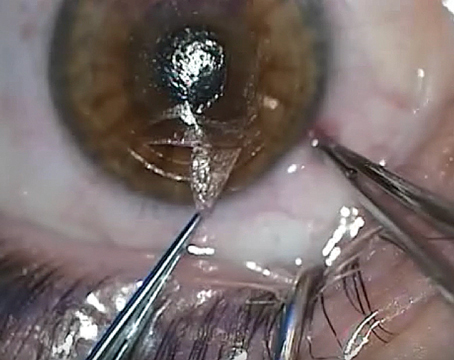

| It helps to perform the anterior dissection first because the posterior side is tethered down and keeps it stable during dissection. |

In light of these issues, I present SMILE in an evenhanded way, and I make sure that I also talk about LASIK and PRK. SMILE is a complementary procedure to LASIK and PRK, not a competitive one. You shouldn’t bash one procedure, such as PRK, to build up SMILE, because this can come back to haunt you should you need to perform a PRK enhancement on the SMILE patient. This goes the other way as well: Most of the patients who come in for refractive surgery want LASIK because of the lack of pain and the rapidity of visual recovery but may not know about SMILE. I inform them that they’re also candidates for SMILE, which has a lot of the same characteristics they’re looking for.

It might also be worth informing the patient that even though he’ll see well immediately after SMILE, the vision won’t be as sharp as with LASIK, at least for approximately the first week postop. It takes a little bit longer for vision to recover with SMILE. Most patients’ vision, however, is equivalent to what you’d get with LASIK after about that first week to the first month.

Procedure Pearls

Getting good at SMILE requires a knowledge of both the technology involved, and the art of manipulating the fragile corneal lenticule.

• Managing preop astigmatism. Since SMILE is only approved for patients with no or almost nonexistent astigmatism, surgeons often ask about performing other procedures beforehand to address cases with astigmatism that’s beyond the approval range. Some surgeons might just perform an AK, combining it with SMILE. But if you do this, I feel you’re shortchanging the patient and the procedure. Astigmatic SMILE should be approved in the next six months or so in the United States. During that time, you have to ask yourself if you’d rather do an AK and combine it with SMILE or just wait until you can simply program the VisuMax to do a compound astigmatism treatment. The latter option is better, in my opinion. If someone with significant astigmatism wants SMILE, I would just tell him to wait another few months, or to have LASIK or PRK now. I don’t think the results of combined AK and SMILE are going to be as accurate as an all-laser SMILE procedure will be.

• VisuMax idiosyncrasies. It helps to become familiar with the VisuMax laser, because it’s different from the IntraLase. The latter is a great machine that works well, but its suction is different than the VisuMax’s. The IntraLase suction is very strong and can cause the patient’s vision to brown- or black out during the procedure, which means suction breaks are very rare with the IntraLase.

With the VisuMax, on the other hand, the suction from the curved applanation cone that goes against the cornea is much lighter than with the IntraLase. Because of this, you really need to get used to the system. In fact, the company requires something in the neighborhood of 30 to 50 LASIK flaps be performed with the VisuMax before it’ll even allow you to perform SMILE with the device, just to help make you comfortable with its suction process. In my experience, this is very astute advice, since I’ve performed upward of 2,000 VisuMax LASIK flap treatments, and I’ve only had a couple of suction breaks, all of which occurred in my first 50 cases. Since then, I’ve had none. Because it has such light suction, then, you have to be aware of patient movement or eye-squeezing, either of which can break VisuMax suction quite easily.

• Controlling patient movement. You’ll find that, when you make flaps or perform SMILE, as soon as you place the speculum or attempt to put in any drops, you can tell if the patient is an eye-squeezer. If he is, tell him to relax and not to clench his jaw or shoulders, which may translate into eye-squeezing. Put your finger on the lid on top of the speculum and note if the patient’s squeezing. If he is, just say, “I can feel you squeezing. Please don’t,” and use your finger in this spot to monitor how much squeezing is occurring, telling him to stop when it happens. This maneuver also helps stabilize the head.

It’s also important to make sure the patient is relatively comfortable and doesn’t move his head or feet. Even moving the feet can cause a movement of the head. I talk to the patients throughout the procedure, informing them what is about to happen and then reassuring them as it does. “As the applanation lens comes down on your eye, there’ll be a circle of white light with a green light in the center,” I say. Once it applanates, the green light will become sharply focused. “Look at the green light,” I say, engaging suction. Once suction is engaged, I tell him not to worry about chasing the light around, but just keep looking straight. I inform the patient that it will take just under 40 seconds, but the first 18 are the most critical because that’s when the power cut is made. If you break suction during that part of the cut, you have to abort the procedure and switch to PRK or LASIK. If you break suction after the power cut, you can just restart the treatment with the anterior or the side cut without a problem.

• After the cut. On the VisuMax, there’s an operating microscope separate from the microscope that you use for the lenticule dissection and removal. Once the cut is completed, you bring the patient beneath that second scope and then use a SMILE dissector instrument to open the side cut, which is 5 mm in length.

With the side cut open, you use a SMILE dissector to identify the anterior and posterior aspects of the dissection. To facilitate this, I’ll move the dissector to one side, for instance the temporal side on the right eye, and identify the anterior-most plane. On the nasal side, I’ll go through the side cut and identify the posterior portion enough so that I can put this spoon-shaped SMILE tissue separator in afterward. Many companies offer SMILE instruments. I started out with SMILE instruments made by Malosa Medical (malosa.com). Malosa makes a pack of single-use instruments exclusively for the steps of the procedure. Today, I use sterilizable SMILE instruments of my own design made by ASICO (www.asico.com).

You always want to separate the anterior lenticule first. If you don’t, the procedure can become quite challenging because there will be nothing to tether the lenticule down. You dissect out the anterior lenticule first, followed by the posterior lenticule. Leave a small bridge of tissue either nasally or temporally to help keep the lenticule tethered in place during the dissection. If you save that tissue bridge for last, you can sweep it aside to easily complete the dissection.

Generally, once you

|

| After removing the lenticule, place it on the cornea and look for any missing pieces. |

After you’ve dissected out the lenticule, it’s critical to then pull it out and lay it on top of the cornea. Inspect it to make sure that it’s perfectly circular, and that you haven’t inadvertently left any pieces in the interface. Laying it out like this will reveal any tears or retained lenticule material. If the tear is small, you can go back into the interface and tease out the remaining tissue. (A feature of the VisuMax that’s helpful for this step is a light similar to that of a slit lamp.)

As you perform your initial cases, you’ll find that visualization of the lenticule can be challenging. Usually, the anterior plane of the lenticule will separate pretty easily, while the posterior one can be somewhat challenging to find. Because of this, I’d strongly recommend that those who are just starting out with SMILE spend time with an experienced SMILE surgeon. Alternatively, have one of the company’s representatives assist you with your first cases.

• Dealing with low corrections. In contrast to LASIK, with SMILE lower corrections are actually some of the trickiest ones. Though this may sound counterintuitive, it makes sense when you think about the mechanics of the procedure: The lenticules in a low correction of, say, -2 or -3 D, are much thinner than those in higher corrections, and are therefore more prone to tears. For example, a -1 D lenticule could be about 25 µm thick, compared to those in -8 or -10 D treatments, which are around 140 µm. Therefore, when you start out with SMILE, it’s probably best to start with corrections in the -4 to -6 D range. This will yield the most satisfying result for the patient and will be easier for you.

Possible Complications

Many of the complications of SMILE stem from the manipulation of the lenticule. However, if you’re careful, you can avoid them in most cases.

• Lenticule issues. If you’re not careful, you can perforate the overlying corneal cap as you’re doing the dissection, causing a tear. If you’re struggling to remove the lenticule, you can accidentally tear the edge of the incision so that it almost becomes more flap-like. Some surgeons have recounted cases in which they couldn’t identify the anterior/posterior lenticule and couldn’t dissect it out. In one such case, the surgeon couldn’t remove the lenticule completely—so he left the piece in the cornea. The patient was dissatisfied with the refractive results and eventually went to another surgeon, who ended up extracting the remaining piece of lenticule a year later without any problem. The patient had a complete recovery and was ultimately satisfied with his SMILE surgery. There have also been cases where this occurred, and the surgeon was able to complete the dissection several months later without incident.

When compared with LASIK, I feel the flap vs. lenticule issues are comparable, but different: You can have lenticule complications with SMILE just as you can have flap complications with LASIK. You can also get a complication such as epithelial ingrowth with SMILE, which is, for the most part, treatable.

• Docking/suction issues. One area where SMILE lags somewhat behind LASIK is in the margin for error you have while creating the lenticule vs. creating a flap. Since this isn’t an excimer laser, there’s no auto-centration or auto-registration. Therefore, it’s critical that you’re docked over the corneal vertex, which usually corresponds to the pupil center. This is because if you get a decentered docking, then you’re going to get a decentered lenticule, which can cause a number of optical issues such as induced aberrations, degraded quality of vision, induced coma and astigmatism, and is very difficult to correct. With LASIK, on the other hand, if your LASIK flap creation is off superiorly or inferiorly by 1 or 2 mm, for instance, and it’s a 9-mm flap, you’ve got some margin for error. This isn’t the case with a lenticule. Centration and not breaking suction are critical parts of the surgery.

• Handling enhancements. As mentioned earlier, the current go-to procedure for a SMILE enhancement isn’t SMILE, but PRK.

If we need to perform an enhancement, we wait a minimum of three months, depending on the amount of initial myopia. For low myopes, such as -3 or -4 D, three months is usually sufficient. For a higher correction, however, we might wait a little longer, maybe six months. Though we haven’t had to do one of these yet, a number of surgeons have shown that PRK works well.

Follow-up and Results

For SMILE, I use the same follow-up schedule as LASIK: topical steroids and a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone, both q.i.d., for a week. I usually see patients on day one, week one, one month, three months and one year.

In terms of results, I’m currently performing my own prospective, contralateral eye study in which one eye gets LASIK and the other undergoes SMILE. I plan to enroll 70 patients. Until that study’s complete, however, there are a few published studies, and the FDA approval data, to draw upon.

In the FDA data, though there were no eyes preoperatively with an uncorrected vision of 20/40 or better: At the six-month visit, 99.7 percent (327/328) and 87.5 percent (287/328) of treated eyes saw 20/40 or better and 20/20 or better, respectively. In terms of predictability, 93 and 98.5 percent achieved an MRSE within ±0.50 D and ±1 D of the attempted correction, respectively. The average preop myopia was -4.75 D (range: -1 to -10 D).

On the complication side, 35 patients out of 336 (10.4 percent) reported moderate or severe glare, and 20 (6 percent) had moderate or severe halos. By month 12, however, there were only four reports of the former (1.1 percent) and one of the latter (0.2 percent). At one year, 2.5 percent (8/311) of patients had lost a line of best-corrected vision vs. preop; no patients lost two or more lines. The rest either improved or stayed the same.

As my experience, and the FDA trials, have shown, SMILE is a safe, effective procedure. However, rather than being LASIK’s replacement, I believe it shines the brightest—and patients and doctors are better served—when it’s positioned as a complementary refractive procedure. REVIEW

Dr. Manche is the director of cornea and refractive surgery at the Stanford University Eye Laser Center, and a professor of ophthalmology at the university. He is a consultant for Allergan, Avedro, Shire, J & J Vision, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Ocular Therapeutix and Avellino Labs.

1. Denoyer A, Landman E, Trinh L, Faure JF, Auclin F, Baudouin C. Dry eye disease after refractive surgery: comparative outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction versus LASIK. Ophthalmology 2015;122:4:669-76.

2. Xu Y, Yang Y. Dry eye after small incision lenticule extraction and LASIK for myopia. J Refract Surg 2014;30:3:186-90.