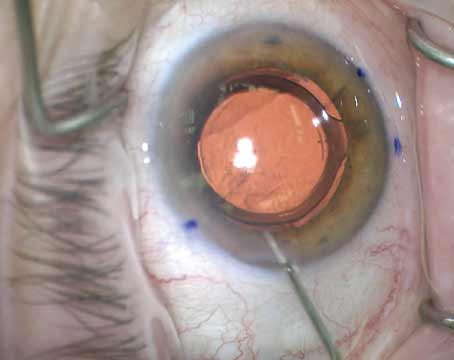

Researchers in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Washington-Seattle have found that undergoing cataract surgery decreases the risk of dementia by about 30 percent. The group’s results were published online in early December in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The prospective, longitudinal study analyzed patients from the Adult Changes in Thought study, a population-based cohort of randomly selected, cognitively normal members of the Kaiser Permanente Washington health-insurance plan. Data on 3,038 patients was collected between 1994 and September 30, 2018. The participants were all at least 65 and dementia-free at enrollment, and were followed until incident dementia. Only patients with a diagnosis of cataract or glaucoma before enrollment or during follow-up were included.

|

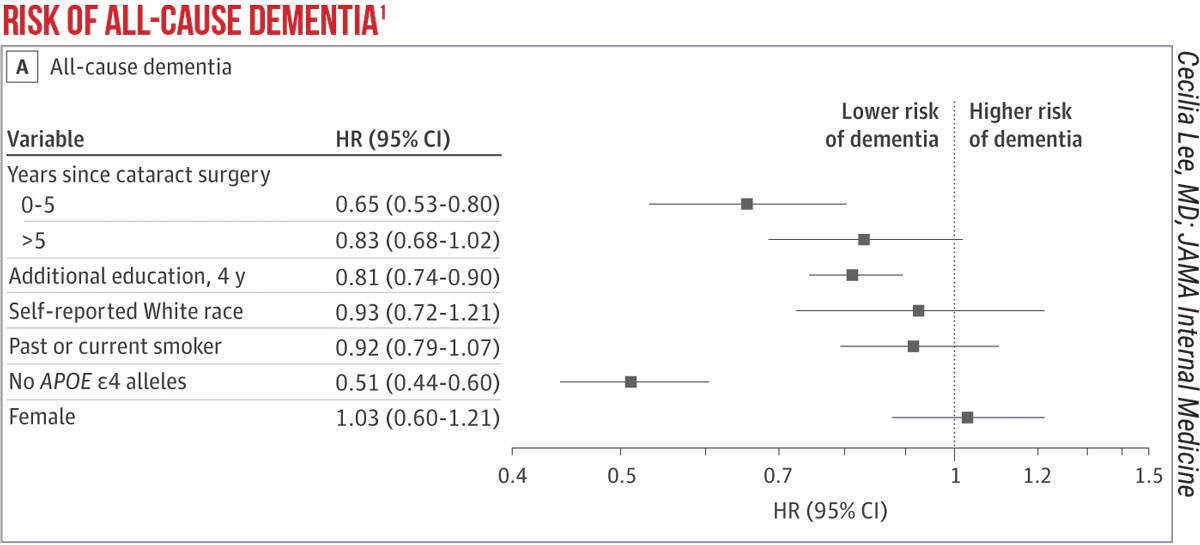

The investigators say that, based on 23,554 person-years of follow-up, cataract extraction turned out to be associated with a significantly reduced risk of dementia compared with patients who didn’t undergo surgery (hazard ratio: 0.71; 95%CI, 0.62-0.83; p<0.001) when controlling for years of education, self-reported White race, sex, age group, smoking history and stratification by apolipoprotein E genotype. They add that similar results were found even after adjusting for “an extensive list of potential confounders.” To isolate cataract surgery as the main driver behind the decreased risk, they even included glaucoma surgery in their analysis and found that it didn’t have a significant association with dementia risk. The researchers say they found similar results with the development of Alzheimer’s dementia, as well.

The study’s corresponding author, Cecilia Lee, MD, was a bit surprised by the result. “Though we hypothesized that cataract surgery would be associated with a decreased rate of dementia, we were surprised by the magnitude of the reduction,” she says, “because there really is no treatment or prevention that’s been reliably shown to decrease the risk of dementia.”

Dr. Lee says they adjusted for many possible confounding variables to get the result. “Confounding factors are important to think about, especially in studies like this that are observational and analyze the effect of a surgery, rather than randomized, in which some people go to surgery and some don’t,” she explains. “One big possible confounder to consider is ‘healthy patient’ bias; for instance, if patients are really sick, such as when they just had a stroke or heart attack, then poor vision isn’t on the top of their list of things to deal with, so they’re unlikely to undergo cataract surgery. On the other hand, people who are healthy and/or health-conscious are more likely to get cataract surgery if their physician recommends it—in other words, maybe the patients in your study who could go for cataract surgery were healthier at baseline. However, since the ACT study patients are members of Kaiser Permanente Washington, we could access all of their medical records, so those confounders could be adjusted for in the analysis. Despite them, we found strong associations with cataract surgery and decreased dementia risk.”

| Letter to the Editor

I read your comments on the Editor’s Page in the November 2021 edition of Review of Ophthalmology with interest. You cited that among AMGA physicians surveyed 22 percent of respondents stated that they would stop accepting new Medicare patients. I am wondering what the statistics look like among ophthalmologists. My guess is the bulk of ophthalmologists will remain as Medicare providers and somehow endure another significant cut to payment. But why are they willing to do this? As a committee member of OPHTHPAC at the AAO, I am incredibly disappointed by the lack of engagement by AAO members in wanting to communicate to Congressional members and also contribute to the PAC. I live in an “oil town,” and I can tell you the participation rate to the American Petroleum Institute by all levels of employees in contributing to their PAC is very, very high. So why do doctors who derive the bulk of their funding from Medicare not participate in the crafting of Medicare funding? It makes no sense at all to me.

Steve Orr, MD |

There are different theories regarding the mechanism behind cataract surgery’s association with dementia. “A common hypothesis is that, when you remove the cataract and your vision gets better, there’s more and better visual stimuli, which may increase the stimulation of the brain, which could be protective,” Dr. Lee says. “Another idea is that, as your vision gets better, you’re better able to engage with the world. This means that you’re more likely to socialize, go for a walk, be less depressed, drive at night, etc. These psychosocial risk factors are known to be associated with dementia risk; they may be improved secondary to having improved vision. The third theory involves a concept called ‘cognitive overload,’ that states there are different loads of stimuli from different sensory systems. If the brain receives a very poor signal from vision, the theory explains, it spends a lot of energy to try to understand the poor visual signals and that confuses and overwhelms the brain.

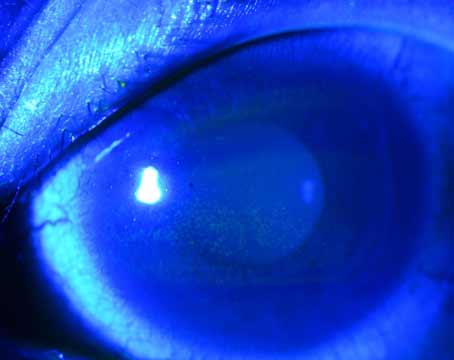

“The theory that’s most interesting to me,” Dr. Lee continues, “has to do with blue light. As you know, when we develop cataracts as we age, the lens becomes yellow, which is especially good at filtering out blue light. There are cells in the retina called IpRGC, or intrinsically-photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, that are known to be involved in circadian rhythms and cognition. There are some reports of Alzheimer’s being associated with those cells, which are sensitive to blue light. So it’s possible that improvement in the quality of light, including blue light, that enters our retina after cataract surgery, might awaken those cells.”

1. Lee C, Gibbons L, Yee A, et al. Association between cataract extraction and development of dementia. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6990. Published online December 6, 2021.