The subject of ophthalmologists co-managing patient care with optometrists has always been controversial. The official position of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, which the column editors (Drs. Netland and Singh) support, can be found online at aao.org/ethics-detail/guidelines-comanagement-postoperative-care. This article presents an alternative perspective.

Health care is an evolving field. Human beings, however, almost always dislike change, and we find it easy to argue for maintaining the status quo. So perhaps it’s not surprising that some evolutionary changes occurring in ophthalmology today are meeting with resistance. One change that’s been occurring—and meeting significant resistance—is the growing prevalence of MDs co-managing glaucoma patients with optometrists.

Here, I’d like to discuss the reasons for this increase in co-management, evaluate the reservations that MDs sometimes express, and share my personal, positive experience working with ODs. As I hope to demonstrate, this shift is happening for a number of good reasons, and it’s part of a larger trend in medicine in which basic care and monitoring of patients with well-controlled disease is gradually being transferred to, or co-managed with, other health-care professionals. In addition, I’ll share some evidence that a team-based approach can end up providing glaucoma patients with timely and complete care.

There are two main reasons that many MDs don’t want to refer to optometrists: the perception that ODs mismanage glaucoma patients, and fear that practice revenue will drop as MDs lose patients to “the com-petition.” My experience has been very different.

How Competent are ODs?

As with many beliefs, the idea that ODs may not be capable of managing glaucoma patients probably started from some poor outcomes in the past that were blamed on inadequate care received from an OD. This has resulted in many MDs making general assumptions about ODs that, in my experience, are simply not true. A few points:

• It makes a difference how extensively an OD has engaged in continuing education. Since the 1990s, glaucoma management guidelines have largely been influenced by the canon of national randomly controlled clinical trials, including the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial, Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study, Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study and Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study. As a result, ODs have had to keep up-to-date by learning glaucoma management from publications and CE courses while in practice. (In fairness, we MDs have had a stronger foundation of medical and surgical management in medical school and residency, but we’ve benefited from CME courses in a similar way.)

Having received glaucoma surgical patient referrals almost equally from ODs and MDs, I’ve reviewed piles of charts from both. I personally have not witnessed a lower level of management quality from the ODs. I see good documentation with re-peated Humphrey visual fields and accurate gonioscopy findings in the charts of my referring ODs. I’ve received letters from referring ODs stating their concern about thinning of the ganglion cell complex on OCT, the Humphrey GPA revealing visual field index loss rates faster than 2 percent per year, a patient’s noncompliance with her CPAP ma-chine for obstructive sleep apnea, and patients’ nocturnal systemic hypotension. The ODs seem to refer promptly when additional management is needed.

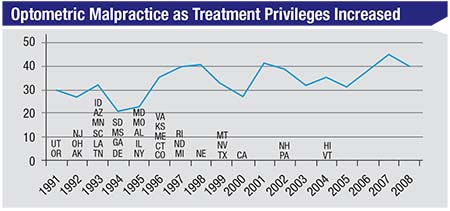

|

| As more states have allowed optometrists to treat glaucoma with drops, one might expect optometric malpractice lawsuits to have increased—if the care being provided was poor. The data, however, indicates no parallel change over time. (Duzak, 2011)1 |

• ODs can identify important clinical findings. I’ve seen instances in which a well-trained OD caught something an experienced MD missed. One example of this hits very close to home for me. One of my relatives was initially diagnosed as having glaucoma by an MD because of “high eye pressures”; the relative used timolol for 20 years.

Eventually my relative saw a local OD whom I respect, whose parents I’d performed cataract surgery on. The OD noted that my relative’s un-treated pressure was only about 22 mmHg, and his cornea was slightly thick—about 570 µm. His nerves looked healthy and his visual fields were completely normal. The OD said, ‘I don’t think you need to be treated.’ It turned out he was correct. Judicious use of critical thinking by an OD well versed in the OHTS long-term results was very helpful to my relative.

In fact, I’ve been a glaucoma sus-pect myself for 20 years, and my grandmother’s eye was enucleated after having had glaucoma surgery. As you can imagine, I take the disease very seriously. But my early glaucoma signs were first picked up by an OD at a routine eye exam, and to this day, both my parents and myself have only been monitored by ODs. Our experiences have led us to have confidence in their ability to do this, and my having a lot of respect for them. Even today, the doctor who measures my IOPs and monitors my visual fields and OCTs is the optometrist in my practice.

• The data suggests that optom-etrists’ care isn’t problematic. Of course, my opinions about optome-trists are based on personal, limited experience. What does the data say?

Consider the chart above, show-ing malpractice claims against op-tometrists.1 Optometrists began to be allowed to treat glaucoma medically (with eye drops) back in 1991. By 2004, almost every state had granted this privilege to optometrists. If they were doing a poor job managing these patients, you might expect the number of lawsuits for things such as not catching glaucoma early, not treating it appropriately or not referring it appropriately, to increase as their scope of practice increased. (Managing glaucoma is certainly a riskier job with more serious con-sequences than prescribing glasses.) But the actual malpractice trend is flat. Furthermore, very few of the malpractice suits against optometrists that have occurred happened because glaucoma patients were improperly managed, or because the optometrist did not refer to, or consult with, a sur-geon in a timely manner.

Of course, not being sued isn’t a surrogate for outstanding clinical pa-tient care. However, many ophthal-mologists assume that optometrists do a horrible job caring for glaucoma patients; that they mismanage and undertreat, and that many of their patients go blind. I hear that all the time from ophthalmologists. Such cases may occur, but the data do not indicate that this is an accurate picture of the overall situation.

If a patient has medically con-trolled, stable glaucoma, it’s a bit like a patient having medically controlled high blood pressure. Such patients may have had no strokes or heart attacks; they’re taking one pill, and now their blood pressure is stable. Today, many physicians have their nurse practitioner see that patient going forward. That’s the case in the Veteran’s Administration system, and it’s becoming the standard of care in many health-care systems. Similarly, my experience suggests that glaucoma patients with nonprogressing, medically controlled, mild-to-moderate glaucoma can be well-managed by ODs.

Will We Lose Income?

That brings us to the second reason for resistance to ODs taking over more glaucoma care: MDs are worried that their practice revenue will drop as they lose patients to “the competition.” There are a number of reasons to conclude that this is not going to happen.

• The number of glaucoma pa-tients is steadily increasing. This is a trend that will continue for many years to come. As the baby boomers age, demand for eye care—especially cataract surgery and glaucoma—will exceed the supply of newly graduated ophthalmologists. The reality is that with a given staff and supply of resources, there’s a limit to how many patients you can efficiently see in a day. Even if you hire more staff, you may not have more rooms. That’s why the typical MD can’t see more than 30 to 60 patients a day. One consequence of that is that new patients will in-creasingly have to wait months for an appointment.

At my previous practice in Brooklyn, the wait time to see me was often three months for a new appointment. That can be unnerving for the patient, and a wait may undercut high-quality health care. (Imagine a patient with severe glaucoma damage and IOPs in the high 30s who has to wait months for a consultation.) At the same time, trying to deal with this by overbooking would often lead to patients waiting nearly 90 minutes to see me, and my discussions with patients were often more rushed that I desired. I was concerned that my patient care was suffering.

I think most busy ophthalmologists are in a similar situation, and the patient crunch is only going to get worse as the baby boomers age.

• We’re detecting glaucoma earlier, increasing the patient load. Thanks to optical coherence tomography we’re learning to identify glaucoma sooner. This technology is allowing us to pick up on mild, preperimetric cases of glaucoma earlier than in the past. As a result, not only will the number of patients be increasing, the number of people with a glaucoma diagnosis is going to increase exponentially as well.

• The number of ophthalmolo-gists is likely to remain the same or shrink. As the number of patients needing care increases, more and more ophthalmologists are retiring, and the influx of new MDs doesn’t appear to be sufficient to meet the increasing demand.

All of this adds up to a simple conclusion: The current situation isn’t going to be sustainable if we hope to be able to see patients within a clinically acceptable amount of time and have impactful chair time. In short, we’re not in danger of losing patients—quite the opposite: We’re almost certainly not going to be able to provide high-quality care to the exploding number of people with glaucoma.

• Patients are demanding faster access and better hours. This is true throughout medicine, and eye care is no exception. Baby boomers are getting more and more active in their retirement, and more and more people are being diagnosed with glaucoma early, before they’re 65, while they’re still working. Working people need to be seen at non-standard times, such as in the evening or on the weekend; they can’t afford to take much time off from work. Today, ODs are often providing that access to care. There are more ODs than MDs, which translates to better access to care in broader geographic areas. Patients tend to think of the care as similar, so they go where the convenience is. Expanding your circle of care to include ODs can lead to happier patients for this reason alone.

• Doing more surgery instead of seeing so many well-controlled patients is not a financially det-rimental proposition. As far as losing revenue if ODs co-manage more of our patients, my experience has been the opposite. Over the past four years, I’ve changed my practice to judiciously refer out certain stable glaucoma patients (especially low-risk glaucoma suspects and ocular hypertensive patients) to ODs whom I trust, while keeping most other glaucoma patients who have uncontrolled IOPs, are rapid progressors, have moderate-to-severe disease, or who have low-teen target IOPs in my practice. I’m booking three times as many surgeries as before, and arguably doing more good for my community with my 30 patients per day than I used to do with 40, because I’m seeing more patients who truly need my expertise. My practice pattern of co-managing with ODs has helped, not hurt, my finances.

Test Case: The Mayo Clinic

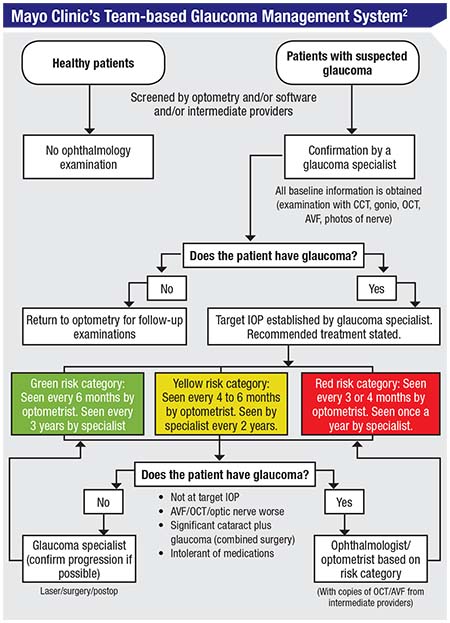

The Mayo Clinic, which is often at the cutting edge of efficient, quality health care, has an excellent team-based eye-care system. This system, diagrammed in the chart on the facing page, was analyzed and evaluated in a study that looked over the clinic’s handling of patients over a 25-year period.2

Here’s how their system works: Patients who have been screened and may have glaucoma are always seen by a glaucoma specialist first. The glaucoma specialist then triages the patient into a high-risk, medium-risk or low-risk category. High-risk patients are seen every three to four months by the OD and every year by the specialist. Medium-risk patients are seen every four to six months by the OD and every other year by the specialist. Low-risk patients are seen by the OD every six months and by the specialist every three years. The ODs handle most of the testing, including visual fields and OCTs. The MDs interpret the test results, deciding what is indicative of progression and what the target IOP for that patient should be. Finally, if the glaucoma is not controlled, the patient is sent back to the MD.

|

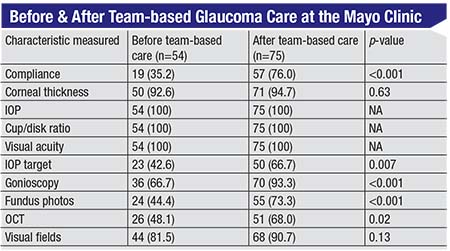

The question, of course, is whether this model actually works. According to the Preferred Practice Patterns designed by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, every glaucoma patient who is being treated properly should have certain testing done. The study authors checked to see how many of these tasks were handled before and after this team-based model was implemented.

The results were impressive. (See chart on the following page.) Before this system was in place, some patients were seen by the glaucoma specialist; some were just seen by the OD. (The doctor that was seen was chosen based primarily on insurance and convenience.) Once the Mayo Clinic set criteria and rules for referrals, more patients had target IOPs set; more patients had their angles checked with gonioscopy; more patients had an OCT done; and more patients had visual fields done. So using this team-based system, compliance with these basic, common sense aspects of monitoring glaucoma was significantly improved.

How Should We Co-manage?

Obviously the idea of ODs and MDs co-managing glaucoma patients isn’t new. But the controversy about this idea in some circles is reflected by a range of rules issued by different states regarding how such co-management must be done—if it’s allowed at all.3

Some states, like Oregon, list specific criteria for when optometrists should refer a glaucoma patient to an MD. New Hampshire, New York and Florida also have specific rules about how and when referrals should take place. In Maryland, where the co-management rules are listed on the state website, an MD and OD must co-sign a detailed contract specifying how the doctors will work together. They have to agree to the number of times a year the patient will get his eye pressure checked, have a visual field and have his optic nerve assessed; what the target IOP is; what drops the patient should be on; and how frequently each doctor will see the patient.

The main problem is, these rules are not based on clinical judgment; they’re based on lobbying efforts by ODs and MDs. In short, lobbying and political pressure are guiding patient care.

Our Approach

I’ve settled on using a variation of Maryland’s system with my referring ODs; I create a co-management plan for each patient on a case-by-case basis. This works well, because the situation is different with each of my four groups of referring ODs. While the first group of ODs is happy to share patient management, a second group tells me they’d prefer to not be involved with managing the patient’s glaucoma at all, so I manage those patients exclusively. A third group of ODs says, “I know glaucoma and I’ve been trained to manage it, but I don’t have an OCT or visual field machine, so I’d prefer to have you manage the patient.” The fourth group only refers me patients who need surgery, or pa-tients with severe disease.

Creating a plan for each patient works well. I enjoy collaborating and discussing the details of the patient’s case. The ODs like it, because they appreciate being treated as part-ners. We’re not following rules that lobbyists got the state board to agree to; we’re working together to do what’s best for the patient.

Often the OD and I discuss the options by phone, text or email. I give the referring OD my recommendation for a target IOP; when visual field testing should be done; what OCT testing should be done; and the guidelines for me being involved. I find out what the OD wants in terms of managing the patient; does he or she just want to see the patient for pressure checks and have him come back to me every year, or just have me see the patient “as needed”? Eventually I have a good sense of how each OD prefers to work with me.

By the time the patient comes in, the OD has already sent me a packet of information showing all of the testing going back years. I love this system because I can spend more time with the patient. I have time to examine the angle and visualize my MIGS options (should I perform a Kahook Dual Blade or an ab interno canaloplasty?) scrutinize the visual fields for the subtlest signs of progression, and have a great discussion with the patient about the options. My morale level is much higher now because the patients are done with the testing by the time they see me. Patient satisfaction is also higher. Now they’re in a good mood and receptive; we can just talk about solutions. And, I’m able to see many more surgical patients.

A Few Suggestions

If you’ve decided to proceed with co-managing your glaucoma patients, these strategies will help.

• Add MIGS to your surgical repertoire. Thanks to OCT, it’s be-come apparent that many individuals have glaucoma even with pressures only in the mid to upper teens. Partly for that reason, over the past 10 years it’s become more widely accepted that the presence of visual field defects indicates that your target pressure should be under 15 mmHg, especially in young patients, African-American patients and those with moderate-stage disease. (The ex-ceptions might include an unusually high IOP due to pigment dispersion, pseudoexfoliation, steroid response, angle closure or herpetic disease.) It’s very hard to achieve that goal consistently over a period of years with eye drops alone. For that reason, these patients may need surgery.

|

| Appropriate testing of glaucoma patients increased in every category that had room for improvement after the team-based approach to managing glaucoma was instituted at the Mayo Clinic. 2 (Numbers in parentheses are percentages.) |

In the past, the only way to get a pressure under 15 was through traditional glaucoma surgery—trabeculectomy or a tube shunt. But when it comes to co-management, many ODs have serious reservations about sending their patients out for very invasive glaucoma surgeries if the goal is only to get a few mmHg of pressure lowering. Now, however, the advent of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery has changed that equation. As suggested by Kuldev Singh, MD, and Anurag Shivastava, MD, our choice of target IOP should be decided in part by the side effects of the intervention.4 So if an intervention has very low side effects—one of the hallmarks of MIGS procedures—we can target a lower IOP with fewer concerns about side effects and complications.

Admittedly, it’s not always possible to get the pressure below 15 mmHg with MIGS alone. However, I would argue that if MIGS can produce a stable IOP in the high teens on one medication, that’s better for the pa-tient than using three medications.

• Perform your own testing if the OD doesn’t have the right equipment. Obviously, the two main ways we monitor glaucoma are with optic nerve imaging such as OCT, and automatic visual fields. Ophthalmologists routinely use both technologies. But from 2001 to 2009, more and more ODs have been monitoring glaucoma using imaging alone rather than doing visual fields, according to a study done by Josh Stein, MD, chair of the American Glaucoma Society patient care com-mittee.5 That’s understandable, be-

cause visual field testing is cumber-some and annoying; no one enjoys doing a visual field test. Furthermore, visual field testing involves a lot more staffing and expense than doing an OCT, which is much quicker, more convenient for the patient and easier to interpret.

However, when you’re managing moderate to severe glaucoma, OCT imaging is not going to be as sensitive as a visual field. Once a patient has visual field defects, you really need to do a visual field to help monitor progression. This stage of the disease simply can’t be monitored with OCT alone. At the practical level, this means that an ophthalmologist should be concerned about referring patients to an OD who doesn’t have an automated visual field machine.

In fact, many ODs currently use an FDT Matrix to test patients. That’s a great screening test to pick up early glaucoma, but it was not designed to monitor glaucoma progression. When I encounter an OD who relies on this test, I explain that there are no clinical trials in which FDT was used to monitor glaucoma. Hence, we cannot provide the most ideal evidence-based care with this equipment. If an OD doesn’t have a Humphrey or Octopus automated visual field testing instrument in the office, I don’t think that a patient with visual field defects can be managed well in that setting. That patient should undergo testing by the MD who does have the instrument.

The same, of course, is true for OCT and early disease. Many ODs who refer to me tell me that they know how to manage glaucoma but they don’t have an OCT, so they’re referring the patient to me. They understand that the data has shown that OCT detects preperimetric glaucoma five to eight years before a defect appears on a visual field. I appreciate that they know how to triage appropriately, and they’re putting the patient’s interests first. I always assure them I’ll send the patient back to them for annual eye exams and glasses.

• Build trust by not duplicating the referring doctors’ services. My current practice is referral-only, so it’s important to us to build a high level of trust with those who refer patients to us. One way we do that is by not having an optical shop.

Most other doctors, whether MD or OD, do have an optical shop. Not surprisingly, they want their patients to come to them for both routine care and glasses. But if you want to earn patient referrals, that won’t help; it makes potential referring ODs hesi-tate because of the distinct possibility that the patient will never return to their practice. One reason our practice has had a good reputation for 20 years is that we don’t do that. We handle the medical/surgical job very well, but we don’t prescribe or sell glasses. We make sure the patient goes back to the referring doctor. Referring ODs know that we’ll let them take care of their patient’s routine eye-care needs.

The Wave of the Future

I define co-management as a colla-borative effort, in which MDs and ODs talk together about what’s best for the patient. This leads to better patient care, and I think it also leads to better doctor morale.

The reality is that medicine is changing. Nurse practitioners are taking over more primary care; cer-tified registered nurse anesthetists are taking over providing ambulatory anesthesia. Letting someone else manage the more basic glaucoma management tasks—especially now that MIGS is making surgical treatment safer and more interesting for the surgeon—is a similar evolu-tionary change. And the number of patients needing treatment is in the process of exploding.

Like it or not, co-management is the wave of the future. Glaucoma is too serious a disease—and there are too many patients—for us to let stereotypes and our egos affect our judgment. We need to work together, and if we can make this new paradigm work to everyone’s benefit, we’ll pro-vide much better patient care. REVIEW

Dr. Desai is a glaucoma specialist at the Witlin Center for Advanced Eye Care in East Brunswick. He received his MD from the Stanford School of Medicine and was a Heed glaucoma fellow at Northwestern University. He is a consultant for Gore and New World Medical.

Much of this material was originally presented in a session at the annual meeting of the American Glaucoma Society in March 2018.

1. Duzak RS, Duszak R. Malpractice payments by optometrists: An analysis of the national practitioner database over 18 years. Optometry 2011;82:1:32-7.

2. Winkler NS, Khanna SS, Khanna CL, et al. Analysis of a physician-led, team-based care model for the treatment of glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2017;26:702-7.

3. Chodnicki K, Jampel H, Saeedi O, et al. A systemic evaluation of state laws governing optometric glaucoma management in the US up to 2015. J Glaucoma 2018;27:3:233-238.

4. Singh K, Shrivastava A. Early aggressive intraocular pressure lowering, target intraocular pressure, and a novel concept for glaucoma care. Surv Ophthalmol 2008;53:S33-8.

5. Stein JD, Talwar N, Laverne AM, Nan B, Lichter PR. Trends in utilization of ancillary glaucoma tests for patients with OAG from 2001-9. Ophthalmol 2012;119:4:748-58.