Because cataracts and glaucoma are both common conditions among older individuals, cataract surgeons often implant lenses in patients who suffer from glaucoma. This raises the question: Why not address the glaucoma via surgery during the cataract operation? Here, I’d like to discuss the issues surrounding this idea, including the pros and cons of combining specific current and impending glaucoma surgeries with cataract surgery, and the reasons that this kind of combined surgery hasn’t yet become commonplace.

To Treat or Not to Treat

Traditional filtering or tube surgery certainly can be combined with cataract surgery. However, trabeculectomy and tube surgeries are associated with a prolonged recovery—not to mention potential complications, both early and late. Another option, Alcon’s ExPRESS Mini Glaucoma Shunt, has been gaining popularity among surgeons performing trabeculectomy. The device is placed under a partial-thickness scleral flap and standardizes the ostium for filtering surgery. It also shortens procedure time and obviates the need for an iridotomy—important factors in minimizing postoperative inflammation and thus facilitating visual recovery. However, despite the benefits of the ExPRESS shunt, the drawbacks of these procedures have made many surgeons hesitant to combine filtration or tube shunt surgeries with cataract surgery, unless the patient has fairly severe glaucoma.

The prolonged recovery associated with these surgeries is especially important in light of the shifting expectations of cataract surgery patients. Cataract surgery has produced increasingly accurate refractive outcomes, and it does so today in record time; but if we do a cataract surgery with trabeculectomy, the patient will take several weeks or months to recover vision. A patient in this situation is likely to say, “My neighbor had cataract surgery and saw perfectly and could drive the next day. But here it is a month after surgery, and I’m still not seeing well.” Considerations like these have motivated many surgeons to simply avoid dealing with the glaucoma at the time of cataract surgery.

Another factor that has become part of the equation is that many patients have a decrease in intraocular pressure as a result of the cataract surgery alone.1 Because of this, many patients will be able to stop medication use, or at least need less medication, following cataract surgery. Thus, there would seem to be some justification for bypassing additional surgery aimed at addressing the glaucoma. In fact, when a patient has very mild glaucoma, I think most cataract surgeons do just the cataract surgery and cross their fingers.

There are two problems with this, however. First, there’s a subset of patients whose pressure doesn’t improve as a result of the cataract surgery. Second, the drop in pressure tends to be relatively small, and many patients need lower target pressures because they have more advanced damage, split fixation, an aggressive family history with the disease, or need to eliminate all medications because of issues involving compliance, cost or side effects. So although the drop in pressure as a result of the cataract surgery is welcome when it occurs, we can’t rely on it as a panacea.

Minimally Invasive Surgeries

For all of these reasons, surgeons have been looking for a way to help these patients by lowering their pressure long-term without jeopardizing the quick visual recovery that patients expect from modern cataract surgery. This has led to increasing interest in the potential of what are being referred to as minimally invasive glaucoma procedures.

Generally, minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries are those that don’t divert aqueous out of the eye in a relatively uncontrolled fashion, which can happen with trabeculectomies or tube surgery. Most of the minimally invasive surgeries are designed to enhance flow through the conventional outflow pathways: the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal.

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries that can be combined with cataract surgery include:

• Trabectome. The Trabectome tool is used to unroof Schlemm’s canal. This is an ab interno approach that can potentially be done through the same incision used for the cataract surgery.

• Endoscopic ciliary photocoagulation. This procedure, also ab interno, ablates ciliary tissue and thus reduces aqueous production. It’s been available for several years, but hasn’t gained a lot of traction in the market. One reason may be that many physicians worry that reducing aqueous production could jeopardize the future health of the eye by risking hypotony. Another concern is that ablating the highly vascular ciliary processes and ciliary body is likely to lead to inflammation, which will delay visual recovery.

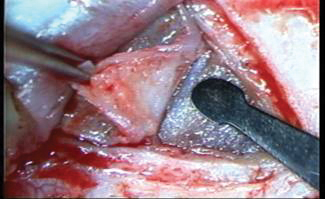

• Canaloplasty. Unlike the other minimally invasive procedures, this is an ab externo approach involving surgery on the surface of the eye, although it’s a non-penetrating procedure. The surgeon creates a conjunctival peritomy and a 50-percent-thickness scleral flap, followed by a secondary flap that extends nearly down to the choroid; this opening is then dissected into Schlemm’s canal.

A small fiber optic catheter is threaded into the canal; the catheter is then used to draw a prolene suture into the canal as it is withdrawn. The suture is tied under a little tension, causing it to act as a stent and open up the canal a little more. Often the internal flap is amputated, allowing a scleral lake to form under the external flap.

|

• The iStent. This is a trabecular micro bypass shunt made by Glaukos, currently awaiting approval by the Food and Drug Administration. (I participated in the FDA trial of the device, and have implanted more of these stents in U.S. patients than any other physician.) In this ab interno procedure, the small stent is placed through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm’s canal, via the existing cataract incision. The stent is designed to allow a more direct flow of aqueous humor into the outflow channels, bypassing any resistance at Schlemm’s canal. The trial of the device, which involved patients with mild to moderate glaucoma on one to three medications, found that about 75 percent of the study group ended up off of all medications with pressures less than or equal to 21 mmHg. Less than half of the control group achieved that outcome. This trial also found that the use of the iStent did not increase the risk of complications of cataract surgery.

The ideal glaucoma procedure to combine with cataract surgery shouldn’t require much change in your approach to the cataract portion of the surgery. One exception to that might be adding a suture when closing the wound. When I do regular cataract surgery, I put a suture in less than 10 percent of the time, but when I do a combination procedure I generally do secure the cataract incision with a suture. This is helpful for two reasons: First, if ocular manipulation is involved in the glaucoma part of the procedure, this could cause some burping of the incision and softening of the eye, making the rest of the procedure more difficult. Second, if the IOP is low in the postop period, a clear corneal incision may not seal appropriately.

Weighing the Pros and Cons

How do these procedures compare in terms of benefits and drawbacks? Factors to consider include:

• Trauma to the eye. The clinical Trabectome data shows that it produces good visual results, but a small number of patients develop hyphema early in the postop period. Blood in the anterior chamber is not conducive to quick visual recovery, and is somewhat pro-inflammatory. As noted, ECP involves tissue ablation and reducing aqueous production, which some surgeons find worrisome, and patients often have ocular inflammation postop.

The issue of inflammation is especially important because of the increasing use of presbyopic IOLs. Today, there are some patients with mild glaucoma who are interested in presbyopic IOLs, and any glaucoma surgery that induces inflammation will jeopardize their visual results. (In the iStent trials, a few patients did opt for presbyopic lenses with good results, but the numbers were too small to draw any significant conclusions. These data were discussed in a poster presented at the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery meeting in 2010, titled “Simultaneous phacoemulsification with presbyopic IOL combined with implantation of a trabecular micro-bypass stent for patients with cataract and glaucoma.”) A procedure that doesn’t jeopardize the visual result is especially important for these patients since they pay extra, raising their expectations even higher.

• Internal vs. external approach. Canaloplasty, as an ab externo procedure, is probably the least surgeon- and patient-friendly of these alternatives.

It involves sutures, conjunctival bleeding and cautery, so it doesn’t leave the patient with a pristine-looking eye. It also jeopardizes some conjunctival-scleral real estate that could be needed for future tube or trabeculectomy surgery. The other three procedures are ab interno, avoiding this disadvantage.

|

• Learning curve and procedure time. Although all of these procedures involve some learning curve, canaloplasty is a more complex procedure, generally considered to have the longest learning curve. Partly for that reason, the procedure can take 30 to 45 minutes when a surgeon first attempts it. However, experienced surgeons may be able to complete a procedure in 20 minutes. The other procedures, utilizing the pre-existing cataract incision, are consistently in the 10- to 15-minute range.

• Cost. The Trabectome and ECP procedures require the purchase of special equipment that’s relatively expensive. Canaloplasty does require some capital investment, although less than the Trabectome or ECP. This may discourage surgeons from trying these procedures. They may think: What if I make a large capital investment and then find I don’t like the procedure?

In this arena, the iStent should have the upper hand; it requires no capital expense other than a gonioscopic lens. The stent itself will be charged to the patient’s insurance. (The actual cost of each stent hasn’t yet been determined.) That means surgeons will be able to try the procedure without a large investment up front.

Ideally, cataract surgeons would like to have an early-stage glaucoma surgical procedure that can be added to cataract surgery but allows a quick recovery and leaves the patient with a quiet eye. For that reason, I suspect that whatever ends up filling this need will be an ab interno procedure that’s relatively straightforward; one that can be learned by a talented cataract surgeon who doesn’t have a glaucoma fellowship; one that doesn’t require significant postop care and management; and one that allows a quick recovery and normal-looking eye, so it will be accepted by patients.

The Patient’s Perspective

Another consideration is what our glaucoma patients want. Many ophthalmologists’ offices have a continuous loop of presbyopic IOL videos showing on the TV. I’ve heard patients say, “The heck with getting rid of glasses—I just want to get rid of these stupid drops!” In fact, if you asked glaucoma patients whether they’d be willing to have a procedure that’s low-risk, doesn’t take much additional time and has a high likelihood of eliminating their need for medications, most of them would probably stand up and yell, “Hooray! Sign me up for that!” That’s why I became involved in the iStent study; a significant number of my patients expressed an interest in finding a way to get rid of their glaucoma drops.

It’s easy to underestimate how important this is to patients. Many patients who are having trouble paying for the drops won’t tell you because they’re embarrassed. Patients who know they frequently forget to take their drops won’t tell you because they don’t want you to think of them as bad people. If we could take the guilt out of it, I think a whole lot of patients would admit to having issues with their glaucoma medications.

Surgeons who offer presbyopic IOLs to their patients have learned that many patients you would never expect to have any interest in a presbyopic IOL turn out to be thrilled with the prospect of getting rid of their glasses—once you ask them. Likewise, doctors who do LASIK sometimes prejudge patients, thinking “This person doesn’t make much money,” or “This person is fine with glasses or contact lenses.” But if you tell everybody about LASIK, you discover there are a lot of people you didn’t think would want the surgery who really do. I believe this is true for patients with glaucoma as well. We’ve all had patients who’ve used glaucoma drops for the past one, two, 10 or 20 years without complaint. If we can offer them a good alternative to that, I think we’ll be amazed at the level of interest we’ll find.

Coming Soon?

At the moment, the options we have for surgically addressing glaucoma during cataract surgery all have downsides. But that will eventually change. My impression is that once a consistent, predictable, effective technology at a reasonable cost to the patient becomes available, we’ll see widespread acceptance from patients. Of course, it might take surgeons a little while to come around; early on, doctors may say, “I don’t use that procedure and my patients do fine.” We may not think much about asking patients to take a drop everyday for the rest of their lives, but our patients could have a very different perspective—especially the younger generation. We’re not dealing with our grandparents, who might have replied, “Whatever you say, doctor.”

In the meantime, consider offering one of the minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries to your cataract patients who have glaucoma. You might be surprised how many of them will be thrilled to accept the offer.

REVIEW

Dr. Buznego is a consultant for Glaukos and part of the clinical trial of the iStent; he owns stock in the company. He has no financial relationship with the other companies or products discussed.

1. Poley BJ, Lindstrom RL, Samuelson TW. Long-term effects of phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in normotensive and ocular hypertensive eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:5:735-42.