Each time we’re faced with a patient with glaucoma—particularly a new

patient—we make a series of judgment calls about what’s wrong and what

we should do in response. Sometimes the nature of the problem seems

clear, fitting our expectations and leading us to respond with triedand-

true treatments. Sometimes the signs and symptoms are far less clear,

and we have to dig deeper for clues.

Should we treat? Should we order extra tests? Should we wait and gather more clinical data over time? Here, I’d like to discuss some of the considerations involved in making those decisions, and offer some suggestions based on my experience.

Is It Really Glaucoma?

Perhaps it’s easiest to categorize new patients into two categories: those whose problem seems obvious, for whom the currently accepted approach to treatment is well-established; and those who don’t readily fall into that category. Both situations raise concerns, albeit very different ones. Patients falling into the second, not-immediately-obvious, category are those that most ophthalmologists would categorize as having normaltension glaucoma. That’s true because in many respects, normal-tension glaucoma is a diagnosis of exclusion. When we find what looks like glaucomatous damage, but the major risk factor associated with that damage—elevated IOP—is missing, we’re likely to have a list of other things to investigate. We need to make sure that the damage we’re seeing really is “only” glaucoma and not secondary to something else that might be putting the patient’s health at risk.

In fact, a number of disease processes have been associated with this kind of normal-tension glaucoma damage. Processes in this category include autoimmune phenomena; autonomic dysregulation, such as highly variable or paradoxical pulse or blood pressure diurnal changes; vasospastic processes such as migraines or Raynaud’s syndrome; vasculopathies (both micro- and macrovascular); thyroid disease; sleep apnea and its accompanying alterations in blood pressure, perhaps including venous pressure in the orbit itself; Alzheimer’s disease; and multiple coagulopathies that are thought to cause microvascular disease within the retina and optic nerve tissue. If you have reason to suspect that one of these conditions could be a factor in the patient’s condition, you’ll have to decide how to proceed.

One obvious possibility is to order additional tests that may provide further information and potentially help the general health of the patient. For example, you might suspect that the patient has a problem with sleep apnea; effective treatment of this condition can make a huge difference in the daily lives of patients, aside from its potential impact on glaucoma progression.

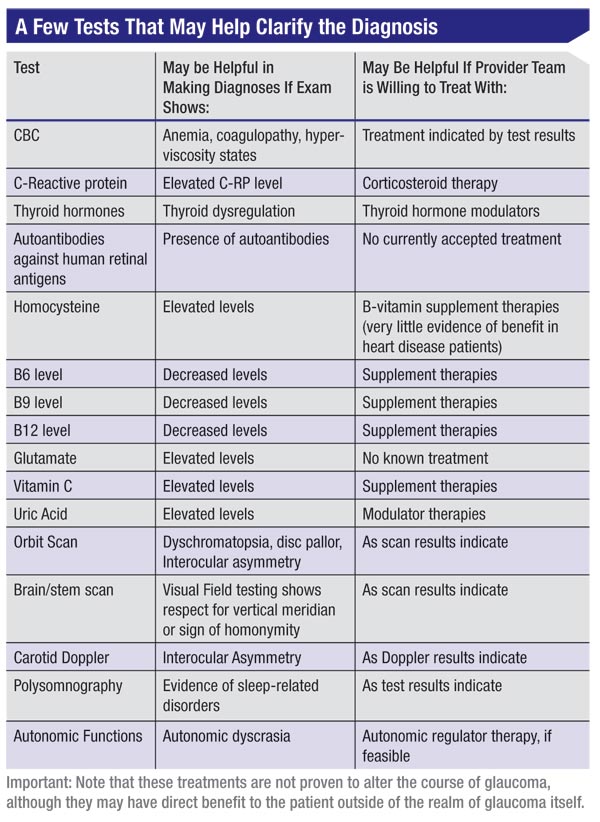

Tests that might be relevant, depending on your findings, could include a complete blood count if you find anemia, or signs of coagulopathy or hyperviscosity states; an orbital scan; polysomnography; autonomic dyscrasia monitoring; neuroimaging; and/or testing for C-reactive protein, thyroid hormones, autoantibodies against human retinal antigens, homocysteine, B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folate), B12 (cobalamin), glutamate,vitamin C or uric acid.

In reality, of course, when faced with a normal-tension glaucoma

patient, no ophthalmologist runs all of these tests as a matter of

course because choosing to order extra tests such as these triggers a

host of other concerns. Tests can be inconvenient and expensive, for

example, with ramifications for both the patient and the health-care

system. The question is, when are extra tests appropriate?

To Test or Not to Test

The decision about whether or not to pursue further testing will be influenced by several factors. Those include:

To Test or Not to Test

The decision about whether or not to pursue further testing will be influenced by several factors. Those include:

|

• The need for a tie-breaker.

One reason we may order additional testing is to serve as a

“tie-breaker” when the source of the damage leaves us concerned that

there is disease, but unconvinced as to the need for treatment. Should

we commit this patient to life-long treatment, or is observation

adequate? Certainly this is an interesting and challenging part of

being a practicing physician—finding yourself in that gray area in which

you have to make a judgment call. In this situation, I believe

anything that can provide extra information that might help me to

actually make a treatment decision that day is a good use of my

resources.

As always, whether or not to pursue extra testing is a judgment call,

but we should at least take such possibilities into consideration. We

don’t want to order unnecessary tests, but we also don’t want to drop

the ball and fail to address a health issue that could be affecting the

patient’s overall well-being—and perhaps even be a threat to the

patient’s longevity.

• The physician’s philosophy. A key factor in how we proceed is how

much responsibility we, as doctors, feel for the patient’s overall

health. As a glaucoma specialist, when the patient is in front of us in

our busy office, it’s easy to limit our thinking and see the patient as a

ganglion cell support system rather than as a person who may need the

benefit of our entire medical training.

Your philosophy might include keeping an eye out for non-glaucoma concerns that show up looking like glaucoma—problems that the patient would benefit from knowing about. Or you may feel that addressing glaucoma should be your primary concern to the exclusion of everything beyond the most obvious health-related danger signals. You don’t necessarily need to go looking for sleep apnea if you think your treatment will take care of the glaucoma part of the problem. Do you order the sleep apnea test yourself? Do you refer to an internist? Or do you limit your thinking and decision-making to the IOP and tell the patient, “You really should have that sleep apnea looked at,” and leave it at that?

In the final analysis, this is a gray, individualized area, with no “correct” answer. In fact, when I presented this topic at a recent meeting, the discussion that followed revealed a wide range of intelligent, differing opinions.

Testing Caveats

Of course, ordering extra tests beyond those we all use entails both financial and practical costs. Some things to consider:

• Costs for the patient. Additional testing in some cases may result in major inconvenience and cost for the patient. Obviously, we don’t want to burden our patients without being fairly certain that the results will make a significant difference in the patient’s well-being and/or quality of life.

• Costs to the health-care system. Today, it’s always possible that an expensive test will impact the overall system and thus affect the care that other patients receive. This can put us in a very difficult ethical spot. In the past few decades, most of us have been able to conduct whatever testing we felt would be helpful. Today, it appears that those days are either already over or will be ending soon. That means we may have to make some very hard choices about whether we can afford all diagnostic and treatment options for every patient in every instance. I already have to argue with insurance companies for testing that they don’t agree is necessary, and there is a significant school of thought that in general, U.S. doctors tend to over-utilize lab and imaging tests. Given that reality, I try to think not only about the patient in question, but about all the other ones who might need this test but will be denied it because the entire line of testing will be shut off or have a higher threshold for approval of funding.

• There’s such a thing as too much information. In terms of ordering the more rarely used tests, an important issue is knowing where the line is between a useful test result and simply having more information. When I was a resident, the phrase was, “What gauge shotgun are you going to use for this workup?” Much of the information these tests can generate is very interesting and theoretically useful, but it’s also subject to the principle of diminishing returns.

So, when I’m in clinic I find myself being much more pragmatic than theoretical. Will the result of this test help me to make a treatment decision today? Increasingly, we’re asked to make as many decisions as we can, as quickly and intelligently as we can. So that pragmatism about “helping me today” is a good filter for deciding about ordering what in some cases would be considered esoteric tests.

• Something suspicious will always turn up. The reality is, the more tests you run, the more likely you are to find something that’s statistically significant simply by random chance, sending you on a wild goose chase.

• Testing can be a way to postpone tough choices. We have to make sure that we really do need the data, and we’re not just using the extra test to postpone making a difficult judgment call on today’s visit.

A Few Specific Tests

Given the average clinician’s limited time and resources, it takes a long time for a test to become accepted and widely used. This is not a six or eight-month process; it’s a five-to-10-year process. Here are some thoughts on specific tests, based on my experience:

• Color-vision testing. In a few patients, I’ve found color vision testing to be helpful as a sign that the problem may be more neurological than glaucomatous—perhaps a vascular or compressive lesion. Thankfully, the need for this has been rare, and my use of it has always been triggered by other signs such as suspicious disc color, or a disc field mismatch. However, when I’ve done the test I’ve found it provided good evidence regarding the need to send a patient for a neurological scan. It’s made a difference for several patients, and it’s easy, inexpensive and noninvasive.

• The C-reactive protein test. C-reactive protein is an indicator of inflammation. C-reactive protein levels may have some value as a tiebreaker in some situations, although there is conflicting evidence regarding its benefits.1,2 All other things being equal, in a patient suspected of having normal tension glaucoma, an elevated C-reactive protein level will make me more inclined to treat with pressure-lowering therapy.

• Neurologic evaluation. The value of this for a patient considered to have normal-tension glaucoma isn’t necessarily clear. One study retrospectively reviewed data from 68 normal-tension glaucoma patients who had received varying levels of neuroimaging and neurophysical exams.3 No abnormalities were found on any neurophysical exam; CT was normal in 88 percent; carotid Dopplers were normal in 92 percent; and no abnormalities were thought to be relevant to the glaucoma findings.

• Orbital scan. It might make sense to scan the orbit for compressive lesions if there are color vision abnormalities, disc pallor or marked asymmetry between the eyes. If there are field defects that hint at a vertical asymmetry or any suspicion of endocrine abnormalities, scanning the brain and brainstem may be indicated.

• Auto-antibody against human retinal antigen. Data in the literature indicates that this test does a good job of identifying normal-tension glaucoma patients, suggesting that normal tension glaucoma really could be a pressure-independent autoimmune phenomenon.4 That would go a long way toward explaining the cases in which I’ve worked aggressively to get a patient’s pressure down to 8 or 10 mmHg, yet the patient still worsened at nearly the same rate as before the pressure was lowered. Unfortunately, this test is still expensive and difficult to do, so its clinical usefulness will remain limited until the test is more readily available and practical.

Sometimes a Horse Is a Zebra

What about the other situation— the one in which the patient does have elevated IOP and classic signs and symptoms of glaucoma? Here, the possibility of missing something less obvious may be greater.

As doctors, we’re trained to look for causes that explain the finding we see. If the constellation of signs and symptoms the patient shows is consistent with a single disease, typically we won’t feel a need to look a lot further. For example, if a patient has obvious visual field loss, a nerve that looks damaged and a pressure of 38 mmHg, we’re not likely to check for brain tumors, because we think we’ve found the cause. As they say, “If it looks, walks and quacks like a duck, it’s probably a duck.”

The fact is, we human beings tend to accept an obvious explanation, if there is one, when we encounter a problem. So if we find damage accompanied by elevated IOP, it’s entirely understandable that we’d proceed on the assumption that glaucoma is the problem. But we shouldn’t be too quick to draw that conclusion; it behooves us to be thorough, even when we do have an apparently obvious explanation.

Making the Tough Calls

Here are some thoughts about our options when faced with a dilemma:

• Don’t be afraid to wait and see. Another disc exam and another visual field in a few months may go a long way to breaking the conceptual tie. To me, the consequences of committing someone to treatment for life are often higher than the probable consequence of waiting one more short cycle to gather one more field or pressure, or a diurnal curve. So in many cases, when I encounter a doesn’t-quite-fit patient, I don’t make a treatment recommendation that day. Of course, this is a judgment call; I sometimes find myself thinking, “If I had that last piece of information that would help me decide today, I’d be three to six months ahead and the patient won’t lose another 1 percent of the neurons I’m trying to protect.” For those patients, expand the testing.

• Work with a neuro-ophthalmologist. I have an easier decision-making process than many glaucomatologists because my academic setting allows ready access to neuro-ophthalmologists. I have the luxury of scheduling that next visual field appointment in conjunction with a neuro-ophthalmology appointment. As a process to facilitate good decision-making for complex problems, nothing beats having the patient and two specialists in the same room. Even if this interaction occurs by phone or e-mail, the most important part is being able to compare notes and discuss until everyone’s satisfied with the thinking and the plan.

• Review the existing data from a different perspective. I find it helpful to consciously change gears from busy-clinic mode to sit-still-and- analyze mode; doing so allows me to be especially thorough. For example, when we first look at a visual field, we’re usually thinking in binary terms: Is this glaucoma or not? Is it stable or worsening? So, when I need further information, I slow down and take a second, longer look and ask different questions. Is this field normal? Could something else be causing this? Is that subtle loss something homonymous? Is it a vertically respecting hemianopia?Could the explanation be in any other part of the visual system besides in front of the lamina cribrosa?

This same idea can be applied to your disc exam, or to reviewing the patient’s history. Typically during the exam we’re scanning for a curvature, a shape, a contour change, and it’s possible to miss a more subtle detail such as noting that one disc is slightly more pallid than the other. So, when you’re in doubt, it might be worth using your indirect ophthalmoscope to check for disc color in the two eyes in rapid succession, or getting a disc photograph of each eye and comparing them side by side.

• Be aware of the possibility of burned-out pigmentary dispersion glaucoma. This is something I learned a long time ago from Robert Ritch, MD. If I see more pigment in the upper angle than in the lower, and I see an iris transillumination defect, one possible explanation for the field loss is that the pressure was elevated decades ago; the pigment has since been resorbed, and the pressure is no longer elevated. I have several patients in this category that I‘ve been comfortable following without treatment. So far, none have progressed.

• Remember to be thorough, even when the explanation seems obvious. Generally, I believe ophthalmologists, particularly glaucomatologists, are a bit like engineers. We tend to be thorough, regardless of the circumstances. But when faced with intense pressure to see more and more patients, it’s easy to reach an obvious conclusion and potentially miss more subtle signs of other trouble. Perhaps the best way to avoid that is to keep this caveat in the back of our minds when we encounter what seems to be a textbook case of high-tension glaucoma. Every so often, a horse does turn out to be a zebra in disguise.

Making the Best Choice

In the final analysis, I believe we need to think on more than one plane at a time. On the one hand, we have to avoid complacency and not be too quick to assume we’ve found the only problem just because we’ve uncovered an obvious problem. At the same time, while tests that go beyond the ordinary measures are important weapons in our arsenal, sometimes waiting for one more exam in a few months isn’t just stalling; it’s actually helpful.

My advice for expanding the range of clinical testing in the workup of NTG is this: If you want to make sure you don’t miss any conditions that can mimic glaucoma, or diseases that could be associated with glaucoma, it may be worthwhile to neuro-image patients who are young and have disc pallor, loss of color vision, carotid bruits, or signs and symptoms of sleep disruption. If your goal is to break a mental tie and decide whether what you’re seeing is glaucoma or not, then lab studies, including autoimmune studies and nutrition blood work, as well as studies of autonomic regulation and ocular blood flow, are indicated.

The central question is, will my choice of action (or inaction) help me care for both this patient’s eye problems and his overall health and well-being? With that as our goal, we’re not likely to go wrong.

Dr. Heatley is associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, and practices at the UW Health Eye Clinics in Madison, Wis.

1. Leibovitch I, Kurtz S, Kesler A, Feithliher N, Shemesh G, Sela BA. C-reactive protein levels in normal tension glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2005;14:5:384-6.

2. Choi J, Joe SG, Seong M, Choi JY, Sung KR, Kook MS. C-reactive protein and lipid profi les in Korean patients with normal tension glaucoma. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2009 Sep;23(3):193-7

3. Kesler A, Haber I, Kurtz S. Neurologic evaluations in normaltension glaucoma workups: Are they worth the effort? Isr Med Assoc 2010;12:5:287-9.

4. Reichelt J, Joachim SC, Pfeiffer N, Grus FH. Analysis of autoantibodies against human retinal antigens in sera of patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Current Eye Research 2008; 33:253-261.