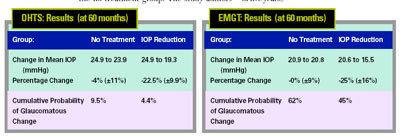

As the data from major studies has accumulated, it's become clear that lowering intraocular pressure really does reduce the risk of glaucomatous damage. For example, consider the data produced by the Ocular Hypertension

Treatment Study and Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial:

• OHTS. This study followed 1,636 patients who had elevated IOP but no objective signs of glaucoma damage to find out whether using topical ocular hypotensive medication would have the effect of delaying or preventing the onset of open angle glaucoma.

Subjects were prospectively randomized to no treatment, or treatment producing an IOP drop of at least 20 percent. Researchers followed their progress for five to seven years. Outcome measures were loss of visual field function or change of optic disc appearance on stereo photographs.

At five years of follow-up, subjects whose pressure was lowered by treatment showed half as much evidence of glaucomatous change as the no-treatment group. The study authors concluded that using topical medications to lower IOP in patients with high pressures does delay or prevent the development of damage (at least in a five-year study).

• EMGT. Here, 255 patients with IOP below 30 mmHg and early visual field defects were prospectively randomized to no treatment, or laser trabeculoplasty and betaxolol, which were used to produce a 25-percent pressure reduction. Patients were followed for an average of six years, looking for field progression or disc changes.

|

|

| The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study and Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial found that lowering intraocular pressure reduces the likelihood of glaucomatous damage, but the benefits were not universal. This suggests a complex relationship between IOP and risk. |

The data showed a significant difference in the rate of progression between the treatment group and the no-treatment group. This benefit was seen in all ages, all levels of IOP at enrollment, and with all levels of visual field loss at enrollment. This suggests that patients with newly diagnosed open angle disease also benefit from IOP reduction. (However, it's worth noting that half of the patients whose treatment produced a 25-percent reduction in IOP still showed glaucoma progression over the course of five years.)

It seems clear that among patients with elevated IOP, including those with concrete signs of early damage, lowering IOP by medication and/or laser delays the onset or progression of glaucoma damage. But the question remains:

Does every mmHg of decreased pressure matter? And if so, does it matter equally?

To find a meaningful answer, we need to break these questions down into several, more pointed questions:

• Is the relationship between IOP and damage linear?

• If not, is there a "safe" threshold below which the risk of damage is minimal?

• Is that threshold the same for all eyes?

• How do we identify the damage threshold?

• Is the likelihood of damage affected by how long the IOP remains above the threshold?

• And finally, what about the practical issue of finding a balance between the risks associated with treatment and the benefits to be gained?

Is the Impact of Pressure Linear?

To find an answer to this question, it's instructive to look at other life situations involving variable change to see whether every unit of change in those situations has an equal effect on risk.

For example, how is our risk of mutation affected by changing levels of radiation exposure? Evidence indicates that at high doses, the risk of mutation (and therefore cancer) is quite linear; more exposure means more risk. However, at very low doses, the impact is far less clear. The rate of mutation doesn't drop to zero even when there has been no known exposure to radiation above normal daily levels. In other words, some patients get mutations even without measurable exposure to radiation. (Does this remind you of normal tension glaucoma?) So in this case, the relationship is not strictly linear.

Can we say the same of glaucoma damage and IOP? Authors other than those originating the OHTS and EMGT studies have examined the studies' data and concluded that each 1-mmHg drop of IOP lowered the risk of progression by 10 percent. However, if every mmHg of lowered IOP really lowers the risk of progression by 10 percent, what happens if IOP is lowered more than 10 millimeters? Does the risk of progression then begin to increase?

The connection between IOP and disc damage does not appear to be linear. And we know that the risk of progression drops dramatically when IOP is low. So, it's reasonable to conclude that there is a threshold below which the risk of damage—at least damage caused by IOP—is minimal. So every mmHg may matter, but only up to a point, depending on the threshold for that eye.

The Healthy Eye Factor

Some evidence indicates that the significance of every mmHg changes depending on the condition of the eye. At a pre-Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology meeting in 2004, Lori M. Ventura, MD, reported using a pattern ERG method to assess variations in ocular function associated with different levels of IOP in several forms of glaucoma. She showed that function improved 40 to 150 percent when IOP was lowered in glaucomatous eyes, but not in normal eyes. So it's appropriate that our target IOP level is usually lower for eyes with advanced glaucomatous damage than for eyes with minimal damage.

The implication is clear: How much risk is associated with a given IOP may depend on the condition of the eye, in addition to the IOP. That means that every eye may have its own IOP threshold, above which the risk of glaucomatous progression increases dramatically.

How do we identify the threshold above which the risk of progression becomes serious for a given eye? Currently, we can't answer that question with precision, although in clinical practice we clearly feel it's possible to make an educated guess. Hopefully, a way to answer this question for each patient will develop as technology continues to advance.

The Treatment Risk Factor

Beyond that consideration, there's another element to the equation. Although reducing IOP clearly has benefits, the methods we use to lower pressure involve some amount of risk. That means we have another important question to answer: "Is every millimeter of IOP reduction worth the risk we take to achieve it?" After all, we know that surgery tends to produce a greater reduction in IOP than medication or laser, but we don't operate on every open-angle glaucoma patient. Surgical treatment carries with it significant perioperative and postoperative risks.

This is the real reason we need to know whether every mmHg matters. If the payoff is less—if reducing IOP another few mmHg won't reduce the risk of progression by a significant amount—the risk/benefit ratio may change in favor of not treating the patient.

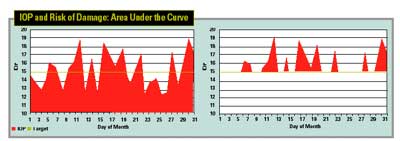

The graph above, left, shows the IOP readings of a hypothetical patient over the course of a month. The colored horizontal line represents a theoretical "threshold IOP," over which damage is likely to occur—a number that would be unique for each individual. Assuming that the risk of progression equals the number of mmHg above the threshold IOP multiplied by the time spent at that IOP, the patient's overall risk could be calculated by finding the area under the curve but above the threshold line (above, right).

The Time Factor

Along with the condition of the eye, another element that must be part of the equation is how long the eye has been subjected to the potentially damaging pressure. This is an issue because IOP fluctuates over time. Obviously, being exposed to high pressure for a brief time is potentially less damaging than being exposed for a long time. And it makes sense that the exact nature of this relationship would be complex, changing as the IOP rises or falls, and changing with the condition of the eye.

Given some of the factors we've discussed, it may someday be possible to determine how much danger is posed by a given amount of pressure, taking into account the period of exposure. For example, the chart above, left, shows the pressure fluctuations of a hypothetical patient over the course of a month. If the doctor were able to determine the threshold IOP—the pressure above which damage is likely to occur, given sufficient exposure, shown here by the colored horizontal line—then the area under the curve, but over the threshold IOP, could represent the patient's risk of progression. (This is illustrated in the graph on the right.)

In our hypothetical example, the "threshold IOP" is 15 mmHg. In this case, even though the IOP readings actually average out to 15 mmHg for the month, the IOP is above that threshold a significant number of days. As a result, it's quite conceivable that progression could still occur in this patient.

Does Every mmHg Count?

All of us know that every mmHg doesn't count equally. That's demonstrated by the fact that we don't operate on every patient who walks into our practice. And because it's clear that damage associated with IOP becomes minimal when pressure is very low, I believe we can state that not every mmHg counts.

However, it's likely that every eye has an IOP safety threshold, and the number of "IOP days" spent over the safe threshold DOES count. Once we have sufficient tools to create a curve like the one in the example above, and we're able to calculate the area under the curve, we'll be able to answer the jackpot question: How much do we need to lower the IOP in this eye to minimize the risk of glaucomatous damage?

Dr. Heatley is associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and is vice chairman for clinical affairs and chairman of the Clinical Working Group at the University of Wisconsin Hospital & Clinics, Department of Ophthalmology.

1. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, Parrish RK II, Wilson MR, Gordon, MO. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:6:701-713.

2. Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, et al., for the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1268-1279.