Diffuse lamellar keratitis, also called the Sands of Sahara syndrome, is a complication of LASIK in which inflammatory cells appear in the interface. Though it’s rare, when it does occur surgeons say quick recognition and treatment can mean the difference between a good outcome and a drawn-out battle that could potentially leave the eye with a refractive error. Here’s a look at the defining characteristics of DLK and how to differentiate it from central toxic keratopathy, a condition that some surgeons say DLK can be mistaken for.

Early Stages of DLK

Many surgeons use the DLK classification scheme proposed by San Diego surgeon Eric Linebarger in 2000 while he was at the Phillips Eye Institute in Minneapolis.1

|

The hallmark of stage-two DLK is that the cells have crossed the pupillary axis and are more diffuse across the interface, say surgeons. “The treatment is hourly steroids, and some surgeons will add a steroid ointment for use at bedtime,” says Dr. Davis. “We check the patient in one or two days.”

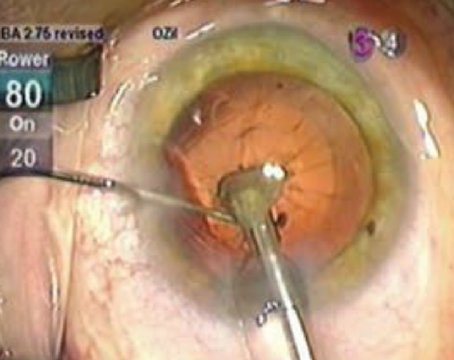

“At stage three you start to see clumping of cells with surrounding clear areas,” says Dr. Davis. Surgeons say this agglomeration can sometimes lead to a decrease in visual acuity.2 “If it is severe, I irrigate under the flap,” says Los Angeles surgeon Robert Maloney. If DLK reaches the third stage, many surgeons agree that removing the cells is important along with concomitant steroid treatment, which may include oral steroids.

In terms of differential diagnosis, Dr. Maloney says there are two other entities to rule out. “On slit-lamp exam, DLK is diffuse and confined to the interface,” he says. “Infectious keratitis, though, tends to extend anterior and posterior to the interface as the microorganisms spread through the stroma, and is associated with inflammation, redness and pain. The other entity to differentiate DLK from is central toxic keratopathy, also called stage four DLK [discussed below].”

Later Stage DLK vs. CTK

Some controversy exists over whether the entity some surgeons diagnose as stage four DLK is actually a different disease altogether, called central toxic keratopathy. Since the treatment for CTK is different from that for DLK, surgeons say it pays to look for certain diagnostic clues.

Dr. Maloney says some cases of DLK can progress to CTK. “CTK presents as an opacification in the cornea, associated with striae, that’s either anterior or posterior to the flap,” he says. “There is no significant inflammation. It seems to be a collapse of the collagen structure because patients tend to get quite hyperopic. The difference between infectious keratitis and CTK is that there is inflammation with infection, and the difference between DLK and the other two entities is whether it’s confined to the interface or not.”

Majid Moshirfar, MD, of the University of Utah’s Moran Eye Center, agrees that CTK needs a different treatment approach, but also thinks it is actually separate from DLK. Dr. Moshirfar believes what is graded as stage-4 DLK is simply the aftermath of an intensive round of treatment for stages one through three, leaving a “burned out” cornea that has a “mudcrack” appearance. For a stage-four DLK like this, Dr. Moshirfar stops the steroid and allows the cornea, often hyperopic at this point, to remodel and heal itself over a period of 18 to 24 months. An enhancement may be required at that point to correct the refractive error.

|

To treat CTK, surgeons advocate backing off the anti-inflammatories rather than ramping them up. “The focus is not to use the steroid,” says Dr. Moshirfar. “If something is killing the keratocytes in the cornea, then we won’t have any more keratocytes to lay down more collagen, so we should treat that. That’s why I put CTK patients on antioxidants in the form of multivitamins, co-enzyme q10, doxycycline 200 mg b.i.d., and 2,000 to 4,000 mg of vitamin C daily. Vitamin C, I think, is useful in a condition such as this because it has properties that help promote collagen, and the doxycycline helps prevent matrix metalloproteinases from destroying more corneal collagen.”

Dr. Moshirfar won’t discontinue the steroid completely, but instead will keep patients on the normal postop LASIK steroid regimen. He says this approach can also help in those CTK cases in which some associated low-grade DLK exists in the periphery. He won’t increase or lengthen the steroid course, however. “The mistake many clinicians make in central toxic keratopathy is to increase the steroid to every 30 minutes or put patients on an oral steroid,” he says. “That’s not the right thing to do.”

Dr. Maloney agrees: “For treatment of CTK, the first point is reassurance,” he says. “This is because CTK always goes away, though it may take six to nine months. Note that it often leaves the patient hyperopic, but it will resolve. The other aspect is the question of treating CTK with steroids or not. I have taken the position that they should not be used, because CTK is non-inflammatory. We’ve published articles that show prolonged steroid treatment after LASIK can lead to end-stage glaucoma,3,4 and it can go undetected because fluid in the flap interface leads to erroneously low IOP readings. So our position is that long-term steroids after LASIK are not a good idea.” Surgeons warn against lifting the flap and irrigating in CTK patients, since they say this will actually wind up removing more corneal tissue than is necessary. They say that this is because the condition apparently involves a process of tissue necrosis in the cornea.

Dr. Moshirfar assures surgeons that jumping on DLK early will solve most potential problems. “The most important thing about DLK is, if a patient comes to you suffering slightly from some visual disturbances, and you see him early on, treat his DLK with a topical steroid and see him every 24 hours. You will hardly ever have to lift a flap and irrigate beneath it,” he says. “In that patient, the DLK will resolve and not move on to stage 3. I have yet to have a stage-4 DLK walk into my office on the fourth or fifth day. And if I do see one classified as such, most of the time it’s probably a CTK that someone deemed a DLK.” REVIEW

1. Linebarger EJ, Hardten DR, Lindstrom RL. Diffuse lamellar keratitis: Diagnosis and management. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1072 1077.

2. Hoffman RS, Fine IH, Packer M. Incidence and outcomes of LASIK with diffuse lamellar keratitis treated with topical and oral corticosteroids. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:451–456.

3. Najman-Vainer J, Smith RJ, Maloney RK. Interface fluid after LASIK: Misleading tonometry can lead to end-stage glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:4:471-2.

4. Hamilton DR, Manche EE, Rich LF, Maloney RK. Steroid-induced glaucoma after laser in situ keratomileusis associated with interface fluid. Ophthalmology 2002;109:4:659-65.