Today, ophthalmologists are well aware that dry eye is a serious issue; it has ramifications not just for patient quality of life, but also for the success of ocular surgery. Nevertheless, it can be challenging to treat effectively, in part because so many different factors can cause its symptoms, and conservative management with over-the-counter tears doesn’t address root causes.

In order to have any hope of addressing those, the ophthalmologist has to start by correctly diagnosing the underlying reason for the problem. Here, with that in mind, experts with extensive experience diagnosing the cause of dry eye share their advice for most effectively getting to the root of the problem.

Confirming Dry Eye

Because confirming dry eye is important (especially if you want to be reimbursed for your time and effort) you first need to know what will serve as confirmation.

“The staging developed by the DEWS 1 and 2 Dry Eye Reports says that if your patient has any ocular surface disease-associated symptoms—even if you don’t find anything on your exam—that is, by definition, Stage-1 dry eye,” explains Francis Mah, MD, a specialist in cornea, external disease and refractive surgery, currently practicing at Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, California. “That’s one reason it’s so important to take a thorough history. If the patient has any type of symptomatology that can be tied to dry eye, that patient, by definition, has dry eyes.”

David R. Hardten, MD, director of cornea at Minnesota Eye Consultants and adjunct professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota, thinks of dry-eye patients as falling into two categories: those who come in to address a dry-eye complaint, and those who come in for some other reason and say, “Oh, by the way, I’m having these symptoms…”

“When patients come in for other reasons, I listen for complaints like tired eyes, fluctuating vision, burning, stinging and/or irritation,” he says. “Depending upon the degree of concern the patient has about those symptoms—and the severity of whatever other problem you’re dealing with—you can approach this diagnostically in a variety of ways. Digging into the history is probably the best way to proceed. That can help you decide whether that patient needs to have dry eye addressed further; how much you need to do to diagnose the nature of the problem; and, if you’ve already started dry-eye therapy, whether to adjust it or try something different.”

One way to elicit dry-eye symptoms is to ask your patients to fill out a questionnaire. “Questionnaires are useful because patients will sometimes not complain to you about problems they’re having, such as difficulty reading, while a questionnaire may reveal the problem,” notes Dr. Mah. “In addition, if a questionnaire is positive for a dry-eye complaint, then you can suggest a point-of-care test, which could be reimbursable.

“We use a variant of the SPEED questionnaire that’s been edited by the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery’s Corneal Clinical Committee,” he notes.1 “Patients can fill it out while sitting in the waiting room or dilating. Or, you can include it in the packet of information the patient receives prior to the office visit.”

Not every practice uses questionnaires routinely. “We don’t give every patient that comes in a dry-eye questionnaire,” Dr. Hardten explains. “We just make sure not to ignore signs or symptoms when we find them. Even then, if the patient isn’t bothered, I wouldn’t do much in terms of treatment. However, if the patient is already being treated for dry eye, we give them a questionnaire to fill out at every visit.”

Making the Exam Count

“Your exam is probably more important than the currently available point-of-care tests when it comes to the diagnosis of dry eye,” notes Dr. Mah. “Pushing on the meibomian glands to assess the oils, measuring the tear breakup time, looking at the overall tear meniscus, and corneal and conjunctival vital dye staining; those are all very important components of dry-eye diagnosis.”

“When we see the kind of patient who mentions dry-eye symptoms in passing,” says Dr. Hardten, “we ask questions like: ‘Do you notice the problem mostly first thing in the morning?’ If so, that suggests that the problem may relate to nocturnal lagophthalmos—sleeping with the eyes partly open. (If you suspect nocturnal lagophthalmos, you can just ask the patient to close the lids gently and then look for exposure or separation of the lids.) Are the symptoms minimal in the morning but get worse over the course of the day? If the patient says yes, the problem could be aqueous tear deficiency, ocular rosacea, blepharitis or evaporative-type dry eye. Burning or stinging can indicate aqueous deficiency or rosacea components of dry eye; foreign-body sensation and tearing can occur with both of these scenarios. Burning and stinging is probably a little bit more common with ocular rosacea—the blepharitis component of dry eye. But it can occur in either type of dry-eye disease.

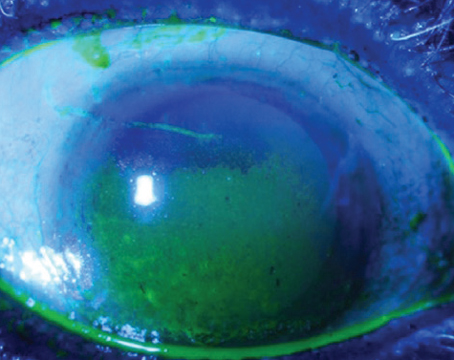

“If you’re managing a patient who’s come in for a checkup or because of glaucoma, and this is the first time they’ve mentioned a dry-eye symptom, fluorescein staining is one of the easiest ways to get a read on the patient’s condition,” he continues. “It’s a quick way to look at the tear-film breakup time. You put some fluorescein in and look for staining of the cornea—and the conjunctiva, although that’s harder to see. Also, look for punctate erosions and punctate keratopathy.

“There are also some pictorial methods for looking at and measuring tear-film breakup time,” he adds. “Those can give you a more numerical analysis than simply putting in fluorescein and looking at the eye. This can be done, for example, with a placido disc topography unit, some of which have specific tear-film protocols. In our clinic we have an HD Analyzer, which analyzes the scattering of light off the cornea after the patient blinks. I find it to be quite useful.”

|

| Here, corneal staining reveals signs of dry eye in a patient. |

It’s also important not to overlook some less-often-recognized symptoms. “Most doctors associate complaints like foreign body sensation, irritation, discomfort and redness with dry eyes,” Dr. Mah points out. “However, fluctuating and occasional blurry vision can also be symptoms of dry eye.

“It’s crucial to listen carefully to the patient during your exam,” he continues. “Fluctuating vision is not a cataract issue! I’ll often do a cataract surgery evaluation, and the patient will say ‘I’m really having problems with reading; sometimes I can read really well, other times I can’t.’ Or they’ll say, ‘I’ll start reading and have to stop after 20 minutes.’ That’s a dry-eye problem.

“Another symptom that can be confusing is excessive tearing,” he points out. “Of course, that can be caused by a more organic issue such as a naso-lacrimal duct obstruction. But often, especially when it’s associated with foreign-body sensation, tearing is a symptom of dry eye.

“I’m sure a lot of eye-care specialists don’t want to get drawn into treating dry-eye disease,” he adds. “Many surgical practices would rather just treat surgical patients. However, if you want better outcomes and happier patients you need to take a little bit more of a holistic approach and try to identify dry eyes and actively manage them.”

| Dry Eye and Allergy “If allergy is a component of the dry-eye problem, there’s usually a significant amount of itch,” notes David R. Hardten, MD, director of cornea at Minnesota Eye Consultants. “However, patients can have mixtures of aqueous deficiency, meibomian gland dysfunction and ocular allergy that lead to a constellation of symptoms that need to be addressed from a treatment standpoint. That means you have to sort out the diagnostics.” Dr. Hardten notes that when you’re checking the lower lid to assess the meibomian glands, you can also look for papillae. “These are characteristic of allergic eye disease,” he explains. “They’re typically minimal in ocular rosacea, blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction and aqueous-deficient dry eye. Papillae are harder to see on the back of the lower lid than on the back of the upper lid, but it’s more work to flip the upper lid. So in an ‘Oh, by the way,’ type of dry-eye complaint situation, it may not be worth flipping the upper eyelid to check. On the other hand, if you’re asking ‘Why didn’t this dry-eye treatment work?’ then flipping the upper eyelid to look for papillae can be quite helpful for distinguishing the symptoms that occur with allergy.” —CK |

Meibomian Gland Dysfunction

“Meibomian gland disease and dry-eye symptoms go hand in hand,” says Bruce Koffler, MD, a cornea and external disease specialist in private practice with Huffman and Huffman, based in Lexington, Kentucky. Dr. Koffler’s practice includes a clinic entirely devoted to treating dry eye. “We keep up with the newest instrumentation and therapies,” he says. “In fact, most of the research we do relates to the ocular surface and dry eye.

“The meibomian glands put healthy oil onto the ocular surface to mix with the aqueous component and make a better, longer-lasting tear, so if the glands have a problem, the tear film has a problem,” he points out. “The formula I learned years ago is: 50 percent of patients with meibomian gland disease have dry-eye symptoms; and 50 percent of dry-eye patients have meibomian gland disease. Meibomian gland disease is certainly very common in our practice.”

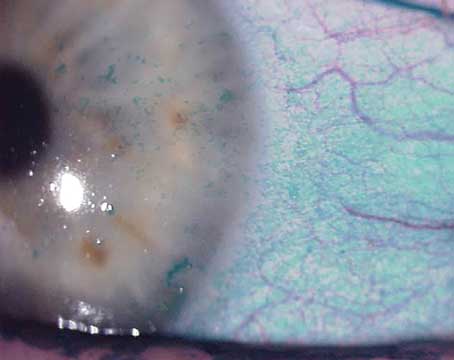

Dr. Koffler says he examines the meibomian glands in every patient that has dry-eye signs or symptoms. “I look for increased plugging of the glands and increased vascularization of the blood vessels around the glands,” he explains. “I always take a Q-tip and do a little expression. I tell the patient I’m going to exert a little bit of pressure on the lid margin—not the eyeball.

“It’s very diagnostic when you gently squeeze the glands and nothing comes out, or you see a toothpaste-like, yellow, purulent discharge,” he explains. “That’s diagnostic of increased Staph activity in the glands, leading to infection, toxin production and irritation of the ocular surface. Eventually it leads to ocular surface problems, as demonstrated by superficial punctate keratitis of the corneal or conjunctival surface, or filamentary keratitis.

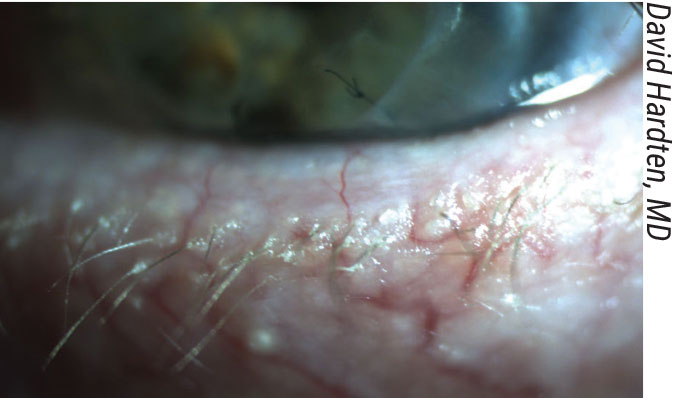

“A lot of these patients are ocular or dermatologic rosacea patients,” he adds. “They need constant therapy. They have problems with the changing seasons, particularly in the spring, summer and fall here in Kentucky where we have a lot of pollen. We’re very much aware of how these allergens affect the eye and the lid margins. These patients have what I call a recovery season in the winter, when I work hard to try to get those oil glands open, reduce the neovascularization, and try to recover to be in better shape for the spring season.”

MGD vs. Aqueous Deficiency

Dr. Hardten says that when a patient mentions dry-eye symptoms in passing, he usually starts by treating with lid hygiene and artificial tears. “These can help with both aqueous insufficiency and meibomian gland dysfunction or ocular rosacea,” he notes. “But if the patient comes back and they’re doing those things and still having trouble, that’s when I try to distinguish between meibomian gland dysfunction and aqueous deficiency in a more sophisticated way. I think most cases are a combination of the two, but usually one is a little bit more predominant.

“A good way to start is to look at the lashes and lids and meibomian glands,” he continues. “It’s often very helpful to use a Q-tip to slightly roll the lower lid out and push on the meibomian glands. You can see whether the material the glands are making is present, and if it’s present, whether it’s clear or turbid.”

“For me, at least, the two tests that I use most often to help with diagnosis are tear osmolarity and meibomian gland imaging,” he says. “If you find significant rosacea, the tear osmolarity test can help you sort out whether the dry eye is mostly aqueous deficiency or mostly evaporative. If the measured tear osmolarity falls below the threshold I’ve set, I consider that to be a case of mostly evaporative dry eye. If the tear osmolarity is high—say, over 310 milliosmoles—or if there’s a big difference between the two eyes—that’s more characteristic of a patient who has significant aqueous deficiency.

“Incidentally,” he adds, “some doctors refer to a lower tear osmolarity measurement as being ‘normal.’ I don’t think that’s a good way to characterize it. I see the measurement threshold as a way to distinguish between two causes of dry-eye symptoms, rather than a normal vs. abnormal tear film. I call it ‘mostly evaporative dry eye,’ not ‘normal.’

“The other test that helps a lot is meibomian gland imaging,” he continues. “Imaging helps me determine the amount of pathology that’s present in ocular rosacea or meibomian gland dysfunction. It’s helpful in determining the degree of gland dropout, and the degree of truncation of the glands or narrowing of the orifices near the exit. It’s a true diagnostic test, as opposed to just pushing on the lid margin—although that’s still extremely useful. A number of instruments can do this kind of imaging. For example, TearScience’s LipiView provides an infrared picture of the meibomian glands. The Oculus Keratograph can do the same thing. LipiView can also look at the thickness of the lipid layer in the tears.

“The other thing we look for is collarettes in the scurf the patient might have along the lashes, indicating a Demodex infestation,” he adds. “If the signs are present, we address this with tea tree oil treatment.”

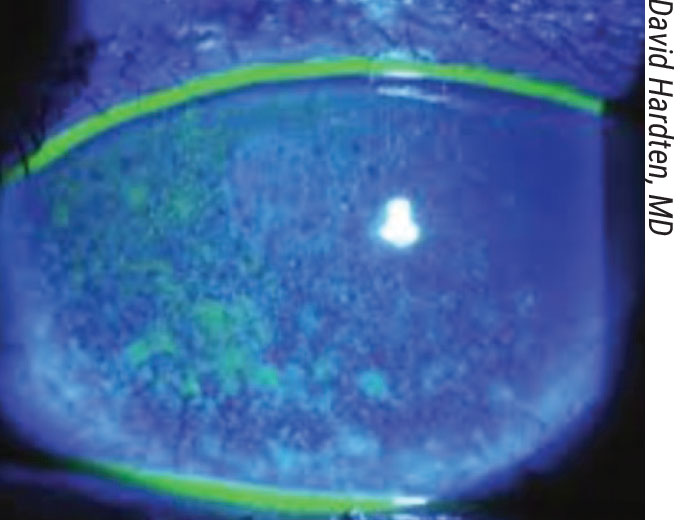

|

| Schirmer’s test: After numbing the cornea, instilling a little fluorescein makes the result much easier to read. |

The Point-of-care Tests

A number of these tests are available. Surgeons offer these observations about the most popular ones:

• Osmolarity testing. Dr. Koffler says he finds osmolarity testing (such as the test produced by TearLab) to be helpful. “Patients who have a high osmolarity score are likely to have dry eye,” he notes. “However, like the Schirmer’s strip, the osmolarity test has to be done properly by an experienced technician, using the proper equipment. Doing the test takes some time and effort, but I do find it helpful.

“Because there’s a Medicare code, we can’t charge the patient if the insurance doesn’t cover the test expenses adequately,” he adds. “Nevertheless, it’s worth doing in select patients, especially if you’re having trouble making the diagnosis.”

• Testing for matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9). “The InflammaDry test is a point-of-care test that’s reimbursed in most situations,” says Dr. Mah. “It’s a colorimetric, yes-or-no test that’s similar to a pregnancy test: If you see a mark, it’s positive; if you don’t see a mark, it’s negative.

“The molecule being measured, MMP-9, has been associated with inflammation around the eye,” he notes. “That means this test isn’t really specific for dry eye, but it will tell you if there’s significant inflammation in the tear film. If there’s inflammation, it could be the result of allergy, blepharitis, aqueous insufficiency or some other issue. This test can definitely be helpful with a diagnosis, especially if you can rule out some of the other inflammatory conditions that might explain the inflammation. And it’s useful for patient education.”

Dr. Hardten says he also sometimes uses the InflammaDry test. “If I have a patient on cyclosporine or lifitegrast, but they’re still complaining and their InflammaDry is still positive, that’s when I consider using topical steroids,” he explains.

• Schirmer’s test. This test has been around for many years; some practices still rely on it; others have mixed feelings about its value.

Dr. Mah says he’s not very enthusiastic about the Schirmer’s test. “It’s very inconsistent,” he notes. “In my experience, unless the reading is close to zero, or the test is part of a clinical trial, or the patient is being evaluated specifically for Sjogren’s disease, it’s not very helpful in the diagnosis of dry eye.”

For those practices that still rely on Schirmer’s, Dr. Koffler offers several tips to ensure useful readings. “First, I instill a little drop of Ophthetic (proparacaine) for numbing before using the Schirmer’s strip, to reduce the amount of reflex tearing that can occur, which can make the test unreliable,” he says. “Second, because it’s sometimes hard to see where the wet zone ends on the strip, I put in a little fluorescein before doing the test; that stains the strip and makes it easier to read when the test is complete. Third, make sure the test is done by a technician who is experienced at doing it, to ensure a reliable result.”

• Meibography. “Meibography is good because it’s very visual and educational for the patient,” Dr. Mah explains. “You can tell whether the glands are present or absent, and whether there’s some knock-out or atrophy. Meibomian gland problems don’t really have much to do with the quantity of aqueous in the tear film, but they have a lot to do with the quality of the tear film and with ocular surface disease. Meibography is very helpful in terms of diagnosing the problem, educating patients and gaining compliance.”

• Topography. “Another sign that your patient has dry eye can be detected via topography,” notes Dr. Mah. “The scan will have little areas of dropout that show up as small blotches here and there, or blank areas that can’t be read. It’s almost impossible for a cornea to actually be that irregular. So if you see that kind of irregularity on a topography scan, one of the first things that should go through your mind is that you’re looking at a dry eye. You don’t need topography to diagnose dry eye, but it can confirm your suspicions and help the patient understand that the dry-eye problem is real, how it might cause fluctuating or blurry vision, and that it requires treatment.”

Today, the plethora of tests intended to help the diagnosis of dry eye has expanded to include specialty options that are part of more complex instruments capable of measuring multiple factors. For example, Dr. Koffler says he also uses the JENVIS Pro Dry Eye Report available with the Oculus Keratograph 5M instrument when diagnosing patients for dry eye. (He has no financial connection to the company or product.)

“The report has multiple components,” he explains. “It gives you an ocular redness score, a tear-lake-volume evaluation and tear-film breakup time, and it images the meibomian glands. It isn’t the highest quality imaging I’ve seen, but you can tell whether the glands are healthy and lined up, or very erratic, scarred-over or plugged. The instrument then creates a report that you can review and share with the patient. It has a scoring wheel showing all of the components it measured. It shows the patient whether they’re in the dry eye ‘danger zone,’ indicated by red vs. green, and you can repeat the report on a six-month or yearly basis, to show patients how they’re improving.”

How many of these tests should a practice aim to have? “Everyone has to do the best they can within the bounds of what’s practical for them,” notes Dr. Koffler. “When you’re in private practice you can only purchase the equipment you can afford.”

Ultimately, how carefully you do your exam and history may trump the number of tests you’re able to offer. “The reality is, right now, we don’t have a really great sine qua non test to diagnose dry eye,” Dr. Mah observes. “It’s not like strep throat, where it doesn’t matter what your exam findings are; if you get a positive strep test, the patient has strep throat. We haven’t reached that point with our dry-eye tests, so the exam is still very, very important.”

|

| A case of ocular rosacea and blepharitis. |

Tips for the Exam & Testing

These suggestions can help make the most of your patient work-up:

• Always check the meibomian glands. “Checking the meibomian glands during your exam is essential,” says Dr. Mah. “Many patients come to see me after being put on one of the four commercial, FDA-approved products for treating dry eyes; they haven’t gotten any better. When I do my exam of those patients and push on the meibomian glands or do meibography, I find meibomian gland problems that haven’t been addressed. That’s why the patient isn’t feeling better.

“It’s a simple test to do—visualizing and pushing on the glands to assess the quality of the meibum,” he continues. “It doesn’t take much time, and it’s not like a Schirmer’s test where the results

can be equivocal. It’s not uncomfortable for the patient. Most important, it gives you a lot of information about the patient’s condition that can dramatically impact the success of your treatment.”

• Consider doing both corneal and conjunctival staining. “We incorporate both of these into our dry-eye testing,” says Dr. Koffler. “We’ve done a lot of dry-eye research using both fluorescein strips and lissamine green strips. Lissamine green stains the conjunctiva better. Sometimes I’ll see conjunctival staining that I don’t see on the cornea, particularly at three and nine o’clock. I believe that’s a good sign of a dry-eye problem. So, I encourage lissamine green conjunctival staining as an additional, affordable, easy-to-do test.”

• Make sure tear-film breakup time is measured by an experienced observer. “There’s a learning curve associated with this,” Dr. Koffler points out. “The better you get at doing it, the more valuable it is.”

• Ask patients key questions about their history yourself. “Today, the history is often taken by a technician,” notes Dr. Koffler. “However, when I see the patient I repeat some of the key questions, such as those pertaining to other systemic health issues like rheumatoid arthritis. I do that because patients sometimes give me a different answer than they gave the technician! The reason isn’t clear, but it happens frequently, and it can make a big difference in your diagnosis.”

• Look for debris in the tear film. Dr. Koffler finds this to be a useful sign of dry eye. “When you’re looking at someone at the slit lamp, if you see a lot of floating debris in the tear film in addition to particles of mucous, that’s a good diagnostic sign for dry eye,” he explains. “Things are landing on the eye’s surface, but they’re not being washed away because there isn’t good tear flow. Increased debris in the tear film is a neat diagnostic tool that many doctors aren’t aware of.”

• Look for filaments on the cornea. “We don’t see filamentary keratitis too often, but it’s very diagnostic of possible dry eye,” notes Dr. Koffler. “Of course, there are other possible causes of filaments that we sometimes see post-surgery, or with superficial limbal keratitis. But if you see filaments and you can eliminate those other possibilities, that’s pretty highly diagnostic of the aqueous form of dry eye.”

• Check for conjunctivochalasis. “My favorite way to look for conjunctivochalasis is to gently press the lower lid up against the globe, put a little bit of pressure on it and move it up and down,” says Dr. Hardten. “If the conjunctiva overhangs the lid, it may be interfering with the flow of the tears on the surface of the eye. This might need to be addressed separately.”

| Testing for Systemic Disease “When you suspect dry eye, the patient should be asked about possible systemic diseases that might produce dry-eye signs and symptoms,” says Bruce Koffler, MD, a cornea and external disease specialist in private practice in Lexington, Kentucky. “I would ask, ‘Do you have any history of collagen-vascular diseases? Rheumatoid arthritis? Mucous membrane issues?’ These questions can lead your investigation in a very different direction.” Francis Mah, MD, a specialist in cornea, external disease and refractive surgery practicing at Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, California, says a thorough history may suggest the possibility of a systemic problem. “If the patient has complaints about dry mouth, issues with eating dry foods and is constantly chewing gum, that might suggest Sjogren’s disease,” he notes. “If your patient has joint problems or muscle aches and pains, that may indicate a systemic problem such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis that has associated dry eye. Those are typically patients who should be tested.” David R. Hardten, MD, director of cornea at Minnesota Eye Consultants, says he may start to consider the possibility of a systemic condition if a Schirmer’s test indicates a very low quantity of aqueous. “I mostly reserve Schirmer’s test for times when I’m considering punctal occlusion,” he notes. “If the Schirmer’s test is very high, I may decide not to use punctal occlusion. If it’s very low, I might start to look for autoimmune conditions like Sjogren’s, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, which are associated with significant aqueous deficiency. In that situation I also may consider blood tests or a mucosal membrane biopsy.” “I usually leave the decision about testing for systemic conditions up to the primary care doctor or rheumatologist, since I’m in a very large multi-specialty group practice,” adds Dr. Mah. “In the meantime, I tell the patient that a systemic problem doesn’t mean I’ll treat their dry eyes any differently; getting those tests done is mainly about improving their quality of life—and those tests may actually extend their life.” —CK |

Other Strategies for Success

These strategies can also help ensure a successful outcome:

• Test all cataract and refractive patients for dry eye. “If a patient comes in without dry-eye complaints, these tests won’t be reimbursed,” Dr. Mah notes. “However, if the patient is being refracted for cataract surgery or refractive surgery, I’d argue it’s worth doing those tests anyway.

“One study found that upwards of 80 percent of patients coming in for cataract surgery evaluation were

asymptomatic—but did have signs of dry-eye disease,” he continues.3 “It would be nice to identify these patients prior to surgery, to make sure you have the best possible biometry. Furthermore, if you treat those dry-eye signs, you’ll minimize any chance of fluctuating vision and less-than-ideal outcomes after surgery … not to mention complaints of dry eye postoperatively.”

• Remember that dry eye can be a bigger problem than the cataract. “If a patient has a 20/200 cataract and a little bit of staining, I take the cataract out and tell them they have dry eye and deal with it,” says Dr. Hardten. “On the other hand, if your patient is 20/20-minus and has to stop reading after 15 minutes because of discomfort, pay attention to those symptoms. Don’t take the cataract out first; treat the dry eye and blepharitis and poor blink response. That’s what’s causing the worst of the patient’s symptoms.”

• Don’t use the dry-eye tests when other tests have just been run. “All patients coming into our practice for a cataract or refractive surgery work-up, as well as any patient coming in for a dry-eye evaluation or ocular surface complaint, are tested for dry eye,” notes Dr. Mah. “If the patient isn’t in for any of those reasons, but I pick up something in the history suggestive of dry eye, we could theoretically do some testing after my exam. However, any drops or testing they’ve already undergone could alter the dry-eye test results. In that situation I may ask the patient to return to have those tests done.”

• Think of the exam workup as a stress test for the cornea. “The workup cataract surgery patients receive when they come in is kind of a stress test,” Dr. Hardten points out. “Before I see them, they’ve had their pressure checked and they’ve sat for a while with dilating drops in their eye. If their cornea looks pristine and topography looks regular, then they’re probably not going to get into trouble with the cataract surgery and I don’t go looking excessively for dry eye. On the other hand, if the cornea doesn’t look very good by the time they get to me, then they’ve failed the stress test.

“For that reason, if their topography and tear film look a little smudgy when I do the cataract surgery evaluation, I’ll ask about dry-eye symptoms,” he continues. “A patient like that isn’t going to hold up well after you do your cataract surgery and make incisions and put them on some toxic drops. That’s the patient who will come back and say ‘My eyes didn’t get better with the cataract surgery,’ and complain about it. So you don’t want to ignore the condition of their tear film after the clinic work-up.”

• Don’t be cavalier about telling patients they have dry-eye disease. Dr. Koffler observes that many surgeons don’t think twice about diagnosing a patient with dry eye. “You have to consider the patient’s perspective,” he says. “You’re telling the patient he has a disease that most likely won’t go away, and it’s probably going to get worse with time. A meibomian gland issue is treatable, but aqueous dry eye isn’t a curable disease.

“I see patients who are upset and miserable because they’ve been told they have dry eye,” he continues. “But when I examine them, I don’t find any dry eye. Meanwhile, they carry that diagnosis to other doctors who may accept it without checking. We shouldn’t give out that diagnosis unless we’re pretty sure about it. If you’re not sure, refer to a doctor who’s more involved with managing dry eye.

Dr. Hardten consults for Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Mah is a member of the medical advisory board for TearLab, and a consultant for Allergan, Sun pharmaceuticals, Kala Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. Dr. Koffler reports no financial ties to any product discussed here.

1. Starr CE, Gupta PK, Farid M, et al. An algorithm for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment of ocular surface disorders. J Cat Refrac Surg 2019;45:5:669-684.

2. Lemp, M. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: A retrospective study. Cornea 2012;31:5:472-8.

3. Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KW, et al. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. JCRS. 2018;44:9:1090-1096.