|

Art imitates life, but sometimes work imitates life, too. This thought occurred to me as I jogged along a rural road in Bomet, Kenya, where I’d moved in 2006 to set up a new, improved vitreoretinal clinic for a local populace who had gone without for a woefully long time. I’d always start one of these runs with the intention to be by myself, with only my thoughts and endorphins to keep me company. This never lasted. Soon, I’d have a crowd of kids following me, calling out, “Mzungu!” (an affectionate term for someone with fair skin) “How are you?”

It was on these runs, surrounded by the folks I was there to help, that I realized that my ambitious goal of establishing a vitreoretinal center, with all of its challenges and unforeseen problems, was going to be a lot more like a marathon than a sprint: You’re not ready to run a marathon overnight, and the race isn’t over until you’ve overcome weariness, pain and doubts of finishing. Work had imitated life.

Here’s my account of bringing the dream of sustainable eye care to a corner of sub-Saharan Africa across the finish line.

An Eye-opening Trip

My interest in global medicine, specifically global ophthalmology, began long before I attended medical school.

I spent one summer in Jamaica after my sophomore year in college, working with a small team of ophthalmologists to provide eye care to communities on the north side of the island. The locals’ access to medical care was limited, and I was humbled by the circumstances and difficult challenges that many of these patients faced. Then I saw the transformation these same patients underwent after having vision-restoring cataract surgery.

My eyes were opened.

I suddenly realized the impact that ophthalmologists could have not just in Jamaica, but worldwide, both in the delivery of eye care and the education of eye-care providers.

I returned to my life in the United States with renewed vigor, and in medical school I investigated which areas of the world had a combination of the greatest rates of blindness and the fewest ophthalmologists per capita. Sub-saharan Africa met both of these criteria. So, in 1998, as a senior medical student, I traveled to Bomet, Kenya’s Tenwek mission hospital to gauge its ability to care for the blind. What I saw when I arrived was a small, 40-year-old hospital with an eye clinic that performed outreach into the community and focused mainly on helping patients in need of cataract surgery. At the time, manual small-incision cataract surgeries were being done by the occasional visiting ophthalmologist and an ophthalmic clinical officer (the Kenyan equivalent of an ophthalmology-oriented physician assistant). Patients with complex eye problems were often referred to Nairobi, Kenya’s capital. This was an unreasonable request, however, since most patients could afford neither the cost of transportation nor the medical care in the capital city. They needed an option closer to home.

It was decided, then: After my two-month medical-student experience, I departed Kenya with dreams of establishing affordable, comprehensive eye care for this community. Seven years later, after completing my ophthalmology residency and fellowship training in vitreoretinal surgery, I returned to Tenwek Hospital to get to work.

Getting Up to Speed

|

We faced many challenges trying to set up a clinic in rural Africa that would be capable of delivering specialized eye care. I spent much of my two-year retina fellowship just preparing for the move to Kenya. For instance, during that time, I intentionally saved all the disposables after each surgical case; with help, I cleaned, repackaged and sterilized them to be used again. I also worked with industry to secure donations of equipment—specifically a vitrectomy machine. I met with private donors to help fund the purchase of other equipment, like a microscope suitable for retina surgery, a variety of surgical instruments, a slit lamp and a laser that could be shared between the clinic and the operating room.

Once I got back to Tenwek Hospital, I spent several weeks learning how the clinic functioned and slowly began to introduce novel ideas, and offer surgeries that hadn’t been done there before. Though I was highly motivated, the first few retina surgeries we attempted were quite grueling—I realized that I should have paid more attention to the excellent scrub nurses I had during my fellowship training. After (re)learning how to maneuver through the menu screens and choose the right settings for the vitrectomy machine, I had taught the scrub techs the same. Though the technicians were accomplished in assisting with MSIC surgery, they had no experience with the computerized machines used in eye surgeries like vitrectomy and phaco. So, personnel training became a necessity if we were to continue using all of this technology. Thankfully, in a short time, these same staff became very proficient with the equipment and are now vital assets to every surgery.

Another hurdle was the potential for poor patient follow-up—once you do a procedure on someone in East Africa, you might never see that patient again. This mandated making clinical/surgical decisions as if this were going to be our last interaction with the person. For instance, a patient presenting with high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy may receive full PRP laser treatment in one session as well as a bevacizumab injection—all at the first visit. With time, however, patients have begun keeping more of their follow-up visits, which has improved our ability to care for their diseases.

The other major challenge is as old as cataract surgery itself: Technology is great until it stops working. The eye staff and myself were excited about the addition of a new array of diagnostic and surgical equipment at the clinic and surgery suite since it improved the care of our patients—until we had our first malfunction. We soon discovered that there was no trained technician in the entire country capable of repairing the devices used in ophthalmology. In response, we had to learn how to solve problems and communicate with technicians in the United States or Europe in order to diagnose and repair the problems.

These experiences emphasized the importance of one of the lessons frequently touted by U.S. Navy SEALs: “Keep it simple.” This rule goes double when dealing with technology in the developing world—keeping diagnostic and treatment paradigms simple helps eye care be more affordable and sustainable.

Retinal Disease in East Africa

|

The prevalence of diabetes is rapidly increasing in Africa; the current estimated prevalence in Kenya is more than 4 percent. This translates to significant diabetic eye disease presenting in our clinics. And, of those patients presenting with diabetic retinopathy, most have moderate to severe disease. Fortunately, in our armamentarium we have lasers, intravitreal medications and vitrectomy surgery to treat these diabetic patients. Several of the anti-VEGF agents are now available in Kenya and, as expected, bevacizumab is the most affordable. We’re working closely with the diabetic medical clinic at Tenwek Hospital to ensure that all diabetic patients receive an annual dilated eye exam and have optimal control of their disease.

As expected in this African population, there’s not much macular degeneration. Those patients who do have this disease usually have a variant like polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. These are typically treated with anti-VEGF injections.

There are also many patients who present with uveitis involving the posterior segment. The burning question is always whether the etiology is infectious or not. Our laboratory diagnostic abilities are limited, but they do allow us to check for HIV, TB and syphilis. At present we don’t have PCR capabilities to look for toxoplasmosis or viral etiologies of uveitis/retinitis, so we have to rely upon our clinical acumen. There’s definitely a higher incidence of TB in the population, leading us to treat empirically for presumed ocular TB in some cases.

| Tenwek Hospital: The Resident Experience Samir Patel, MD As a resident, my short-term global ophthalmology experience in rural Africa provided a limited, but important, perspective on the unique considerations surrounding international ophthalmology. Having arrived in the second half of my third year of residency, and having already matched into a vitreoretinal fellowship, I was particularly excited to spend two weeks with Dr. Roberts and the entire ophthalmology team at Tenwek Mission Hospital in Bomet, Kenya. Dr. Roberts is fellowship-trained as a vitreoretinal surgeon, and Tenwek Hospital is one of only a handful of referral centers in Eastern Africa that have the resources to treat retinal pathology. As an aspiring retina specialist, I was eager to learn about the practice patterns of a vitreoretinal surgeon in this environment. Opened in 2018, the Tenwek Eye and Dental Center houses the clinic and operating rooms, and the physical environment is almost identical to what you’d expect in the United States. By design, Dr. Roberts has labored under the conviction that every patient—whether in rural Kenya or back on his furloughs in Alabama—deserves the same excellent, compassionate care. Since his arrival in 2006, Dr. Roberts has expanded Tenwek’s ophthalmology department into a tertiary eye referral center that’s able to manage nearly any ocular pathology. On the edge of the Rift Valley, the clinic is filled with the latest gadgets, including optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography, B-scan ultrasonography, digital fundus photography, laser indirect ophthalmoscopy and pattern-scanning lasers. My clinic days were charged with the feelings of a final exam: Some of the most obscure diagnoses you’d expect to see only on a standardized test were daily walk-ins at the Tenwek Eye Clinic. Furthermore, I was most surprised by the degree of complexity of common pathologies. For example, the vast majority of patients with retinal detachments in Eastern Africa will never have access to a retina specialist, so they’ll go untreated. The patients who do present to the clinic almost always have chronic detachments with extensive proliferative vitreoretinopathy and a prognosis so poor that they require combined treatment modalities, such as combined pars plana vitrectomy, scleral buckling and silicone oil. Just like the clinic, the operating rooms are equipped with the latest technologies, including Alcon Constellation vitrectomy machines using 23-, 25-, and 27-ga. systems and Zeiss microscopes. All surgeries are performed using the Resight noncontact viewing system, and there’s access to endolaser, perfluorocarbons, SF6, C3F8 and silicone oil. In addition to retina surgeries, the operating rooms are equipped for corneal cases, including corneal transplants and cross-linking; cataract surgery using phacoemulsification or MSICS; and glaucoma surgeries, including glaucoma drainage implant devices and cyclophotocoagulation. I found that the clinic and operating rooms face unique challenges because of working in an environment where nothing is thrown away or wasted. It was humbling to discover that a significant proportion of my perceived surgical skill was directly attributable to the state-of-the-art equipment and supplies we had available in the Wills Eye Hospital OR. In this rural environment, there’s no option to buy another device when the first one breaks, or to bring in on-site technical support. You’re as much a surgeon as you are a technician who can take apart and repair complex machines. One of the long-term goals of the hospital is to help local ophthalmologists take the reins of their community’s health care. The hospital serves as an educational site for trainees of all levels, including medical students, interns, residents, consultants and regional ophthalmologists who hope to specialize in retina care. Dr. Roberts and the entire ophthalmology department have created a unique niche within the global ophthalmology field, and I look forward to witnessing the continued expansion of its ophthalmic community. |

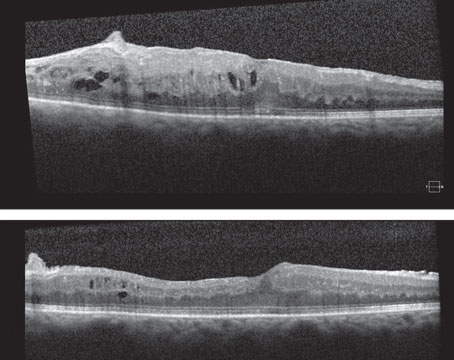

The problems related to vitreous and vitreoretinal interface (vitreomacular traction, macular hole, retinal detachment) are similar in incidence to what’s found in the United States. The only difference is the time to presentation after these problems first occur. It’s not uncommon to have a patient present with a large chronic macular hole in one eye and a smaller, recently occurring macular hole in the fellow eye. Similarly, patients with retinal detachments usually don’t present in a timely manner. Over the past 15 years, I’ve treated hundreds of patients with detachments, but fewer than 10 were truly macula-sparing. As quality, affordable eye-care centers evolve in sub-Saharan Africa, I can only believe that patients will present sooner when their vision deteriorates.

Strategies for Care

As alluded to above, there are many challenges in bringing quality vitreoretinal care to the rural, low-resource settings of sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainable technology, reliable supply chains and affordability are all barriers that need to be addressed.

In our effort to provide improved care for our patients at Tenwek, the greatest strategy involves better education and training. There are some talented, very skilled ophthalmologists delivering excellent eye care across the continent, but very few are trained vitreoretinal specialists. Most countries don’t even have retina training programs, requiring interested African ophthalmologists to leave their country—and often the continent—to receive fellowship training. Depending on the program, the quality of that training varies widely.

At Tenwek, we’re doing our best to contribute to the training of young ophthalmologists, enabling them to grow in experience and confidence as they join the battle against blindness. While we don’t have an independent ophthalmology residency, we do work closely with the only recognized residency program in the country, located in Nairobi. Many of their residents do rotations with us to gain both clinical and surgical experience.

As far as vitreoretinal training goes, we’re working with the few other retina specialists in the country to establish at least one, and hopefully several, retina fellowships, to increase the number of qualified vitreoretinal specialists in Kenya and East Africa. This will no doubt help meet the growing demand for VR surgeons. Two years ago, a young Kenyan ophthalmologist, Catherine Kareko, who had completed a one-year retina fellowship outside of the African continent joined our team. She was looking for a place equipped to provide retina care where she could be mentored and gain experience. Over the past two years, she has flourished and is now one of the growing leaders in this subspecialty in Kenya.

The Right Reasons

|

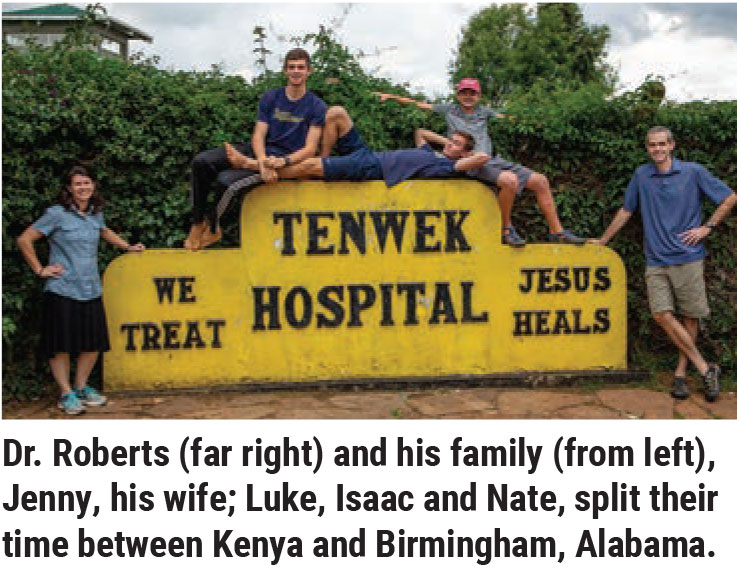

I’ve been working in Kenya for 15 years now, in rotations consisting of four years in Africa followed by one year back in the States, and will be returning to Africa this August. As you’ve read, it’s been immensely rewarding.

After reading this account, then—or maybe hearing about other physicians’ experiences—you may be thinking of getting involved in global eye care yourself. After all, you’ve likely got the skills to dramatically change a person’s life: Offering vision to patients, especially to those who are truly blind, is a gift like no other. Indeed, there’s been a significant increase in interest and involvement in providing eye care to underserved areas over the past decade on the part of U.S.-trained ophthalmologists. But before diving head first into a global ophthalmology adventure, even if you’ve already had some international experience, make sure you’re doing it for the right reasons.

The main thing is to understand your motives for going. There are some good—even great—reasons for participating in global eye care, but there are some undesirable—and possibly destructive—reasons for participating in global ophthalmology, as well. For example, if your underlying motivation for involvement in an eye mission is to have an adventure and see “exotic” parts of the world, then you’ve merely become a medical tourist; this can be detrimental to the patients and communities you intend to serve. If you think your western training is unparalleled, and your goal is teaching the locals “your way” of doing things, then you may be teaching skills and techniques that are inappropriate and unsustainable for that culture.

On the other hand, if you want to donate your time and resources to providing eye care for a local community that otherwise wouldn’t receive it, that’s a very good thing. But I challenge you to consider an even better purpose. Go beyond just providing care and take the opportunity to train local eye-care providers, empowering them to care for their own people. All the while, do it with humility and a willingness to become a student of their culture. This is the type of purpose that can have an incredible impact on both the individuals and the communities you serve.

Be sure to keep these goals in mind as you run toward the finish line in the long, sometimes arduous, trek to providing medical care to those most in need of it.

Dr. Roberts is ophthalmologist-in-chief at Tenwek Mission Hospital in Bomet. He’s also a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Alabama in Birmingham.

Dr. Patel is a pursuing a Fellowship in retina at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia.