How has the cataract surgery landscape changed since premium IOLs were introduced 35 years ago? And how has the landscape changed since the femtosecond laser debuted in 2009? Most important: How have you and other ophthalmologists responded? “These days, the short answer to all three of those questions is very quickly,” says Michael Greenwood, MD, a cataract and refractive surgeon who also specializes in glaucoma and cornea at Vance Thompson Vision in Fargo, North Dakota. “We’re used to seeing new technologies come along every few years, but now it seems like it’s almost monthly. The outcomes are getting better and better. Surgeons are growing more comfortable with the newest technology, and, as a result, patients are benefiting from an explosion of innovations.”

Other surgeons report similar impressions. In this article, the ones who are increasing their success with premium cataract surgery explain how they incorporate new IOLs into their practices, identify ideal surgical candidates, promote the refractive benefits of surgery, organize staff around new team approaches to screening and presentation and use femtosecond laser technology to master the best techniques. The surgeons also offer advice to get you started on the path to similar success.

Recent Rapid Evolution

Dr. Greenwood says the premium IOL market really started to gain momentum with the introduction of low-add multifocals several years ago, even though haloes and glare were still issues. “Now we’re in the era of trifocality and extended-depth-of-focus, and that has allowed even better distance and near vision and even better intermediate vision, which had been the least-beneficial feature of past premium lenses,” he says. “Along with the functional improvements found in trifocals and EDOFs, the dysphotopsia profiles have gotten even better. So now surgeons and patients can have a lot of confidence, knowing that outcomes are going to be good. And the trade-offs found in the dysphotopsia profile will be very mild compared to the benefits patients will get from the presbyopia-correcting lenses.”

Dr. Greenwood says his practice used to have 35 to 40 percent of patients choosing some kind of premium option to minimize their dependence on glasses. “But as we come out of COVID, the numbers have crept up a little bit. And that’s probably because of patients’ ability to prioritize their vision a little bit more,” he says. “Patients may have more money available because of less vacation time. A variety of factors have come into play.”

Ideal Candidates = Success

When earlier generations of premium IOLs first became available many years ago, the surgeons at Eye Centers of Tennessee began to implant thousands of the new lenses, believing a new day in surgical excellence and outcomes had arrived. But a troubling trend soon followed.

“More and more patients came back, and they weren’t very thrilled with their vision,” says Michael Patterson, DO, a comprehensive ophthalmologist at the practice. “The surgeons in our practice couldn’t figure out why this was happening, because the patients could see 20/20 on the eye chart. Since then, though, we’ve learned they weren’t happy because they hadn’t been good candidates. We learned more about dry eye, high angle kappa, and other challenges to optimal postop vision that hadn’t entered our thinking before.”

Currently, he says, the practice has adopted ever-advancing diagnostic technologies that have enabled surgeons to confidently tell patients if they’re good candidates for an increasingly sophisticated array of premium IOL technologies which, like the lenses, have grown more sharply focused on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

“Now that we can more accurately predict good candidates and identify patients who aren’t good candidates, we’ve achieved a much higher satisfaction ratio with premium IOLs than we had in the past,” says Dr. Patterson. “Whether it be from us using OCT on the retina, corneal topography on every single patient who’s getting a premium lens, or other tests, we can now tell patients, definitively, that they’re great candidates for particular lenses. We can almost guarantee that they’ll see 20/20, but, most importantly, that they’ll be satisfied with their vision before we do the surgery.

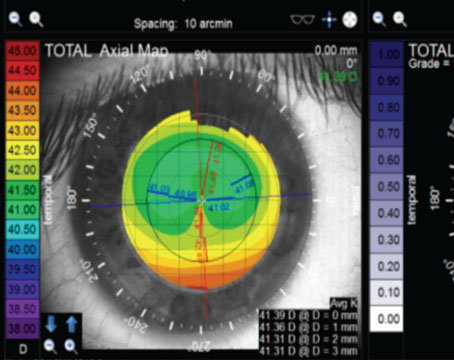

|

| Figure 1. A NIDEK OPD III image provides various data, but surgeons say one of the most important points when considering a patient for premium IOLs is the “total cornea HOA,” or higher-order aberrations measurement, which helps to determine if a patient would be a good multifocal IOL candidate. |

“This is certainly a game-changer in ophthalmology because, previously, the message was, ‘We’re going to get you seeing the best we can,’’’ he continues. “This has helped with our chair time in the clinic, too, and it also helps postoperatively. Our assistants and coordinators know they’re not going to have to spend a lot of time with unpleasant surprises and unhappy patients. If we’ve identified patients as ideal premium lens patients preoperatively, we don’t need to have these difficult conversations. That’s a huge advantage in the use of premium lenses today.”

Dr. Patterson notes that the other important part of this growing success story is the evolution of the IOLs. “The newest IOL technologies, primarily from Johnson & Johnson Vision and Alcon, have enhanced lenses to the point where glare and halos haven’t been as significant a problem during the past two to three years,” Dr. Patterson continues. “For example, in the Alcon lens, the company increased the center button to put more distance vision through that area. The reason that helps is because it causes fewer halos and less glare in the company’s ActiveFocus IOL. The Johnson & Johnson Symfony offers a similar process. And now J&J has just launched the Tecnis Synergy lens, while Alcon had previously launched PanOptix [and recently launched the Vivity]. These combinations have given patients better choices for improved vision, with a greater range.”

Refractive Cataract Strategies

Dr. Patterson says his practice embraces refractive cataract surgery to meet two needs:

• patients’ desire to wear no distance glasses, enabling them to drive without them, guaranteed; or

• patients’ desire to not wear glasses for distance and near.

“Our refractive cataract volume has grown 10 percent to about 35 percent of 4,000 cataract surgeries per year,” he says of the 10 locations at Eye Centers of Tennessee. “That’s high for us because many patients around here don’t have a lot of extra money to spend. We’ve been able to achieve this because we have so much confidence in the premium technologies we have today. We can totally guarantee what we say we’re going to do.”

Optimism is somewhat guarded at some practices, however. Alan Aker, MD, who owns and operates Aker Kasten Eye Center with his wife, Ann Kasten, MD, in Boca Raton, Florida, remains mindful of how the sometimes over-promised and under-delivered performance of yesteryear’s premium IOLs has affected surgeons’ reputations and patient confidence.

“We had a number of factors working against us in the past,” he says. “The patients who received those lenses couldn’t drive at night, and doctors stopped implanting them because of these issues. Many surgeons didn’t know,⎯or didn’t want to know, how⎯to replace the lenses. And that remains a big issue. When you put in a lens, you have to know how to take it out to replace it with a lens that satisfies an unhappy patient.”

The newer IOLs, he acknowledges, have significantly changed the dynamics in the marketplace. “We can put in lenses without trepidation over the potential for more disappointments,” he says. “All the lenses that are currently available have advantages and disadvantages, but we’ve definitely seen improvements.”

Dr. Aker’s enthusiasm for today’s premium IOLs has translated into a conversion rate of more than 70 percent of his practice’s 2,500 cataract surgery patients per year into premium lens patients. However, he emphasizes that premium lenses aren’t for every patient.

“You have to manage expectations,” he notes. “I tell patients that there’s no perfect lens, and there may never be.”

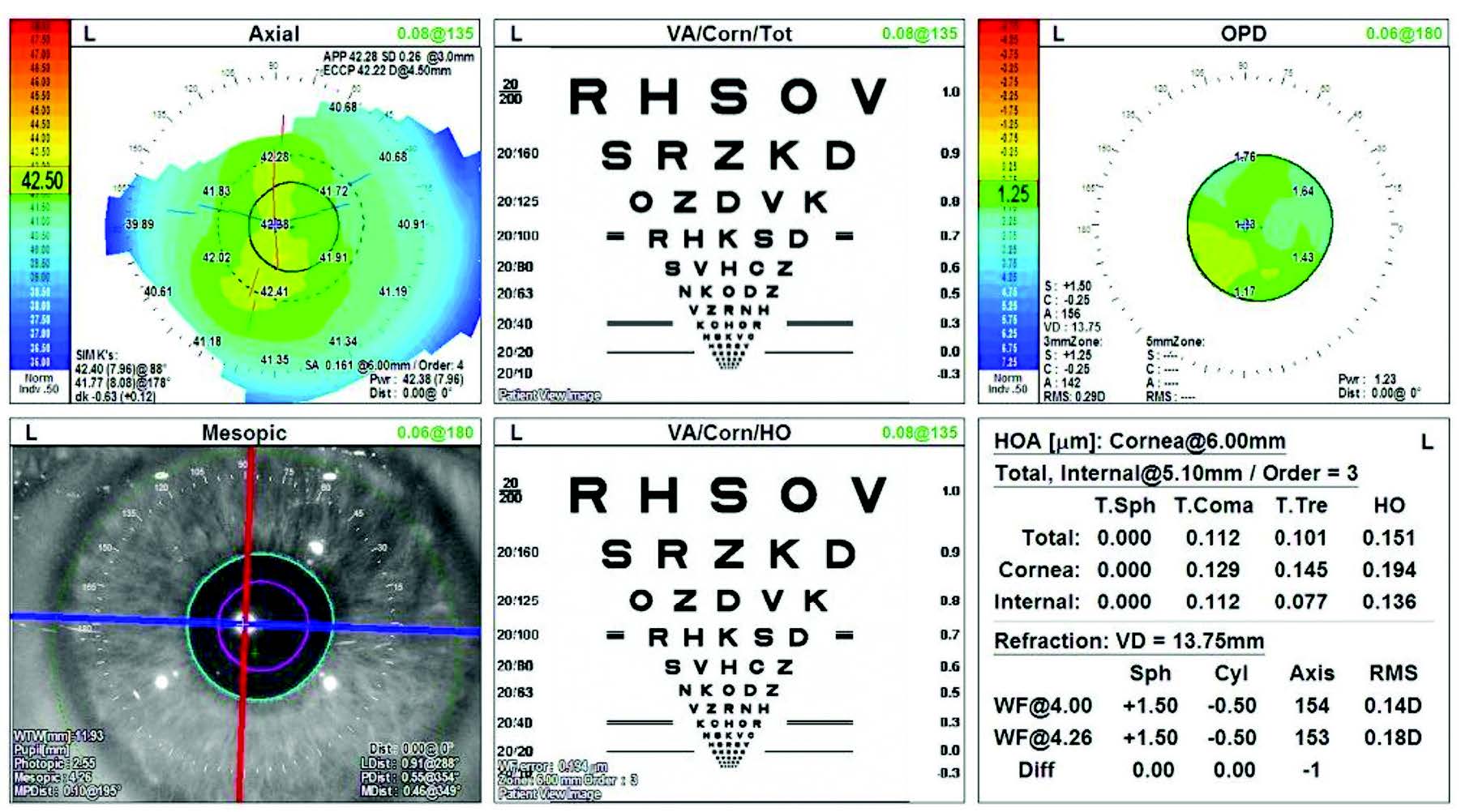

|

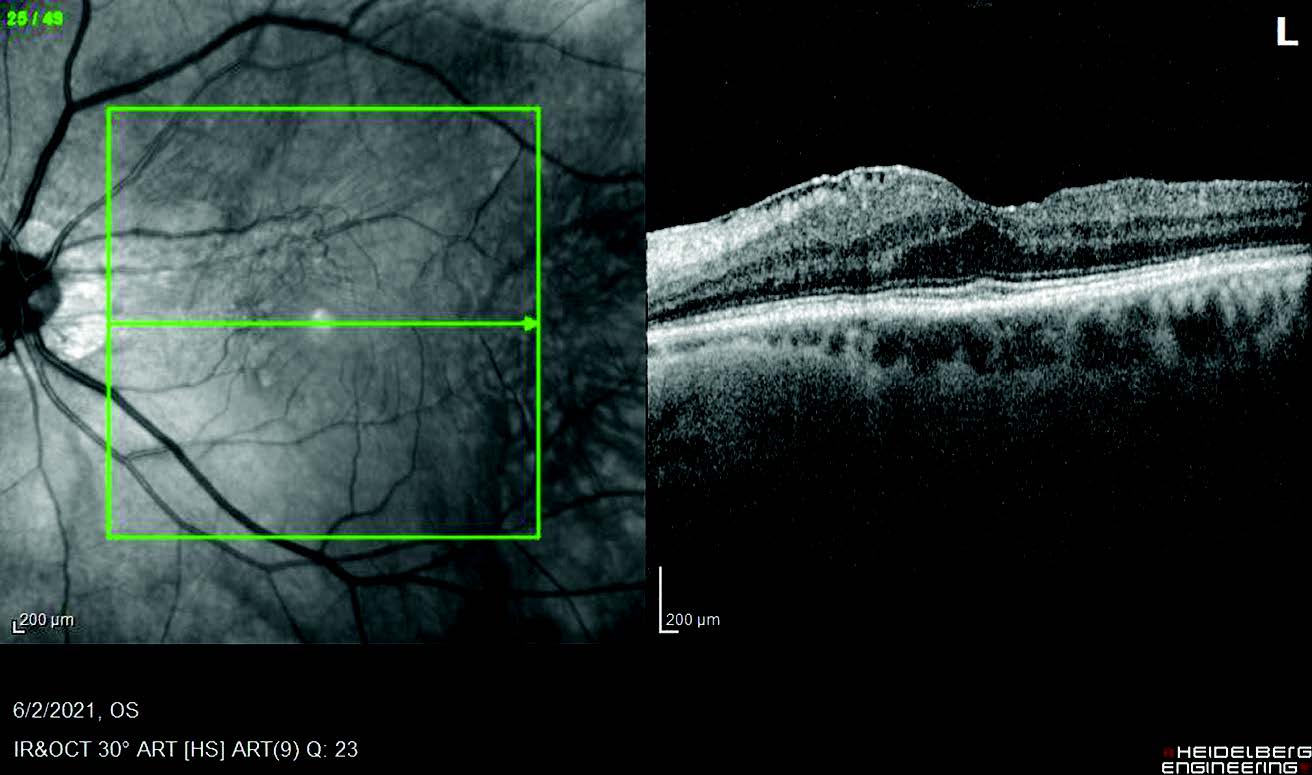

| Figure 2. This macular OCT scan shows loss of foveal depression following an epiretinal membrane peel. Surgeons say the loss of foveal depression tells this surgeon his patient isn’t an ideal multifocal IOL candidate. |

He urges colleagues to be aware of potential variations in outcomes among patients, sometimes for reasons that don’t seem discernible. “Some patients get extraordinary results,” he observes. “They can read like a champ and see distance like a hawk,” typically in IOLs not designed for near vision correction.

“These outcomes are great, of course, but you have to watch for word-of-mouth success stories that can create unrealistic expectations among patients referred to you by their extremely happy friends,” he continues. “We tell patients, ‘You may have heard of some patients that have done really well with reading with these lenses. If you get that, consider it a bonus, because the lens doesn’t normally perform that way.’ We try to stay ever mindful of the lessons we learned not so long ago. You always want to under-promise and over-deliver.”

R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, Louisiana, and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Louisiana State University and Tulane Schools of Medicine in New Orleans, says major improvements in the refractive benefits of today’s lens-based surgery have led to much more patient satisfaction, even with standard monofocal IOLs. “Today’s surgeon now has better tools to take the refractive benefits to the next level by allowing more dependable reduction in spectacle dependency for distance and near vision,” he notes. “We’ve learned that, with clinic teamwork and effective preoperative patient counseling, successful postoperative outcomes can be achieved.”

It Takes a Team

In the old days, surgeons say, the complex challenge of explaining various IOL options was often left to the surgeon, one-on-one with the patient. Leaders of the most successful premium practices today ask all employees of the practice to share in this core responsibility. That means everyone from the front desk staff to the business staff to the techs in the back office. Some surgeons have designated specialists who dedicate most or all of their time to educating and screening patients for premium IOLs.

“We look for severe dry eyes,” says Megan Flatt, COA, Dr. Patterson’s executive surgical assistant at the Eye Centers of Tennessee. “We don’t want to add to those problems with surgery, especially with premium IOLs. We explain to potential surgical candidates that the cornea is their front window that they’re looking through. So if they have a disruption on the cornea, they’re not going to see clearly, even with a premium technology lens. Even if it’s perfectly centered in the bag, their quality of vision is still not going to be optimal because of a cornea that’s not. Sometimes you need to spend a little time with them to get these ideas across. Some other factors that we rule out are any retinal problems, any glaucoma, or high angle kappa and alpha issues.

“We do have patients who still want to have the technology,” she continues. “But we set the expectations with the patients. ‘Hey, listen,’ I’ll tell them. ‘You’re not a perfect candidate for this option. But if you still want that technology, we may need to change the lens we’re using for the surgery. You’re not going to see perfectly at some ranges because it doesn’t provide the perfect near qualities that you’d like to have, for example. But we can give you a lens that reduces the chance of glare and halos.”

Dr. Wallace relies on similar support in his practice. “If you don’t use a team approach for a refractive cataract practice, it doesn’t work so well,” he says. “Most significantly, the team members need to know how important they are in this effort. If they’re not integral to the success of this whole system, then they’re not going to give you what they can give you in terms of quality of care for the patients, and they aren’t going to enjoy what they do, which is very important as well. It’s critical that they be educated.”

Bill Wallace, MBA, Dr. Wallace’s son and the practice administrator, carries the same message throughout the office and into the practice’s ambulatory surgery center.

“I recently delivered a spotlight talk on refractive cataract surgery to the staff,” Mr. Wallace says. “One of the measures of success is the enthusiasm we see in our employees. They want to know more about the options that are available, and they’re always asking for additional presentations to make sure they’re up to date. To see this staff so hungry for the information they need to make sure we’re successful is a clear indicator that we’re doing things right. We have patients who come in for multiple visits before deciding on their surgery. This isn’t a decision that’s made during one visit. It speaks to the notion that this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Robert Crotty, OD, a doctor at the practice, whose office desk sits across from Dr. Wallace’s, also plays a key role in evaluating, educating, screening, following up and caring for cataract surgery patients. He even lectures at state optometry meetings to teach ODs how to help drive the success of a refractive cataract surgery practice.

|

|

|

“The newer lenses have opened up the door to allow these patients to become candidates for premium service,” says Dr. Crotty. “However, screening these patients is very important. Just this morning, we caught an epiretinal membrane when screening for a patient’s preferred type of lens. That pathology obviously limited the kind of lens choice we would recommend. Had it not been for that screening, this patient could have become one of those patients who could’ve ended up unhappy.” (See Figure 3 above.)

Dr. Crotty places equal importance on patient education. “The more patients learn, whether it’s from the staff or the doctors, there’s always more to tell them to clarify, confirm and expand on their knowledge base. By giving patients this information, they know that we’re providing them with the best opportunity to make a once-in-a-lifetime decision to seek the best care they can get for their eyes. When we see a patient who’s delighted with his or her surgical result, that’s what really gets us excited. That’s what we call ‘sharing the value.’”

To support his efforts, Dr. Greenwood says he and his fellow surgeons rely on what he describes as five or six “touch points” to educate and advise patients on today’s complex IOL offerings. “One touch point can come from the referring optometrists, although that’s not expected,” he says. “Another touch point comes when we send patients something in the mail, whether it’s a mail offer or a mail/text video that they can view. Another touch point is what we put on our website. When patients visit our office and communicate with staff while they get testing done, that’s another touch point.

“When the doctors visit with the patients, that’s another touch point,” Dr. Greenwood continues. “And while the doctors are finishing everything up regarding the discussion, and the patients are making their decisions, that’s just another touch point and an additional time for education. I’d estimate that 95 percent of our patients make the decision on how they want to proceed during that first visit. But again, we’ve done a lot of education on the front end, so these are informed decisions.”

Increasing Team Skills

The Privatization of Surgery? Is the federal government gradually privatizing cataract surgery? It would seem that way to some surgeons. If you’re maintaining a robust surgical practice, investing more in diagnostic technologies, a bigger and better support staff, marketing muscle and facilities needed to deliver premium cataract surgery, you may share this sentiment. If you’re sticking to basic cataract surgery, you may also be wondering how you’ll get by when shrinking reimbursements from Uncle Sam turn your care and service into a commodity business that you can’t continue running on your own. “What we do for a living is definitely moving toward privatization, to a large extent,” says Alan B. Aker, MD, who owns and operates the Aker Kasten Eye Center with his wife, Ann Kasten, MD, in Boca Raton, Florida. “When I got into practice in 1980, reimbursement for cataract surgery was $2,800 per eye. Now Medicare pays $547 per eye. We do commercial cataracts (through HMOs), primarily in hopes that patients will want to upgrade to the femtosecond laser and premium intraocular lenses to benefit from the best care and outcomes that we’re able to offer. But some of these patients are only interested in basic surgery, or they’re not appropriate for premium lenses.” The typical fee Dr. Aker earns for one of these basic “commercial” cataract procedures ranges from $350 to $400, he says. “When you subtract the other fees that are involved, our fee decreases to $280 for cataract surgery,” he points out. “Think about that. That’s insane.” As cuts in cataract surgery reimbursements have accelerated during the past 20 years, Dr. Aker notes that many surgeons have worked hard to maximize efficiencies, decrease procedure time, reduce complications, increase volume and improve outcomes. However, these strategies, especially those focused on increased speed and volume, can’t be used to gain, or in some cases, maintain ground in today’s practice economics—especially as practices invest more in the human and technical resources and consultative time needed to build premium practices that can provide a hedge against the erosion of revenue earned from Medicare. “With these premium IOLs, the lens manufacturers are trying to eliminate dysphotopsias, which have been the Achilles heel of premium IOLs,” Dr. Aker observes. “If we can minimize the halos and glare, patients will want those lenses. Is that bad? Well, we’re selling expensive lenses because the patient wants better products. The government says they can buy these better products. And to offer premium lenses, we need to increase the cost of what we do. That’s why it’s called a premium package.” Dr. Aker acknowledges that continuing cuts in reimbursements may not represent the complete privatization of cataract surgery. “But the survival of practice is involved,” he adds. “If the reimbursement goes below $500, I believe a lot of doctors will stop doing routine cataract surgery. They’ll opt out and make more money by fitting contact lenses than they will by sweating it out in the OR with a difficult case. The alternative is to embrace new ways of practice. We’ll still do the regular cases, recognizing that a lot of patients can’t afford to pay for a premium lens. But if surgeons can supplement the regular cases by doing enough of the premium cases, then they can make it. Their practices can be strengthened financially. It’s really all about basic practice economics.” — SM |

Some practices are creating unique positions to help develop their premium practices. For example, at the Aker Kasten Eye Center, Jeffrey Rapp, who has a PhD in human physiology, serves as director of patient education and IOL selection or, as Dr. Aker describes his role, “medical science liaison between surgeons and patients.” Dr. Aker adds: “Dr. Rapp has the scientific knowledge needed to grasp the technical and surgical aspects of what we do, yet he’s very adept at communicating to patients in a way that conveys the correct information succinctly without overwhelming them with the clinical details of surgery.”

Dr. Rapp also assists on a variety of technical issues at the eye center. For example, during the past year, he played a role in 1,500 femtosecond laser cataract procedures, entering patient data, setting criteria for astigmatism correction values and type, inputting capsulotomy locations, and, when applicable, iris registrations. But perhaps Dr. Rapp’s greatest impact has been felt in educating and consulting with patients on premium products and services at the eye center

“What we were doing with patients before surgery in the past was a mistake, jamming everything into one visit,” says Dr. Aker. “The patient was basically trying to drink from a fire hydrant. After explaining the premium lens options available for his or her eyes, when you announced that it was going to cost more than $6,000 for both eyes, the patient would get a bad case of sticker shock. He or she would look like a deer in the headlights, ready to run from any thought of what we’d just recommended. What Dr. Rapp does that’s different is present a series of outcomes, and we’re letting the patient choose the outcome,⎯not the price,⎯first.”

Dr. Rapp reaches out to potential surgical candidates about a week before their appointments, explaining to them what their visits will entail. “Under the old approach, patients would come into our practice under the assumption that they might have cataracts,” Dr. Rapp says. “I tell them if we find a need for surgery, we’re going to go through a very detailed series of measurements and study to really identify their individual anatomy. We’re going to determine what’s going to be the safest procedural method, plus one, two or three types of lenses that will be agreeable. And the lenses are going to work. ‘No matter which of them you choose, you’re going to have a great result,’ I tell them. ‘It’s just a matter of how far you want to go with the benefits of the latest technologies.’”

The length of Dr. Rapp’s calls ranges from 20 minutes to an hour, during which he asks many detailed questions to focus on patients’ visual needs and desires. “‘What do you do when you wake up in the morning—do you put your glasses on?’” I ask them. “Do you like your glasses or do you hate your glasses? Do you drive at night? What kind of activities do you like?’ Through these conversations, I walk them through every potential outcome. That gives them time to research the options and think about what they might really like. They can converse with their friends, family and spouses to get comfortable with their choices. And we talk about prices, too, well before they come into the eye center.”

To Femto or Not To Femto?

Many surgeons who launch or expand premium cataract surgery practices employ, at least temporarily, the use of the femtosecond laser or the Zepto (for capsulotomies). In addition to performing some of the steps of the cataract procedure, the femtosecond laser can also create corneal incisions to correct astigmatism.

The balance sheet challenge of using femtosecond laser, including purchase prices of up to $500,000 and pricey usage fees and maintenance contracts, often determines if surgeons will use the technology as a permanent service. Other factors can also play a role.

“I’d say the femtosecond laser is a great technology,” says Dr. Patterson, whose practice leased a femtosecond laser for cataract surgery from 2015 to 2017. “For our system, however, in which we used the femto in one room and performed the surgery in our single OR, it slowed us down and it didn’t change our refractive outcomes. Femto gave us great outcomes, but we had manual outcomes that were just as good. Therefore we decided it wasn’t in the best interests of our company to continue with the technology.”

He adds that the financial burden of femto on patients was also a consideration. “We were already charging patients for a premium lens outcome, not a process,” he says. “In our demographic, our patients are much more interested in premium technology when the price is reduced. When we were using femto, we had to charge an extra $1,000 to $1,500. Now that we’ve removed that charge, more patients have adopted the lens technology. We practice in a rural setting. As I mentioned, we don’t practice where there’s a lot of money. So these were the main considerations involved.”

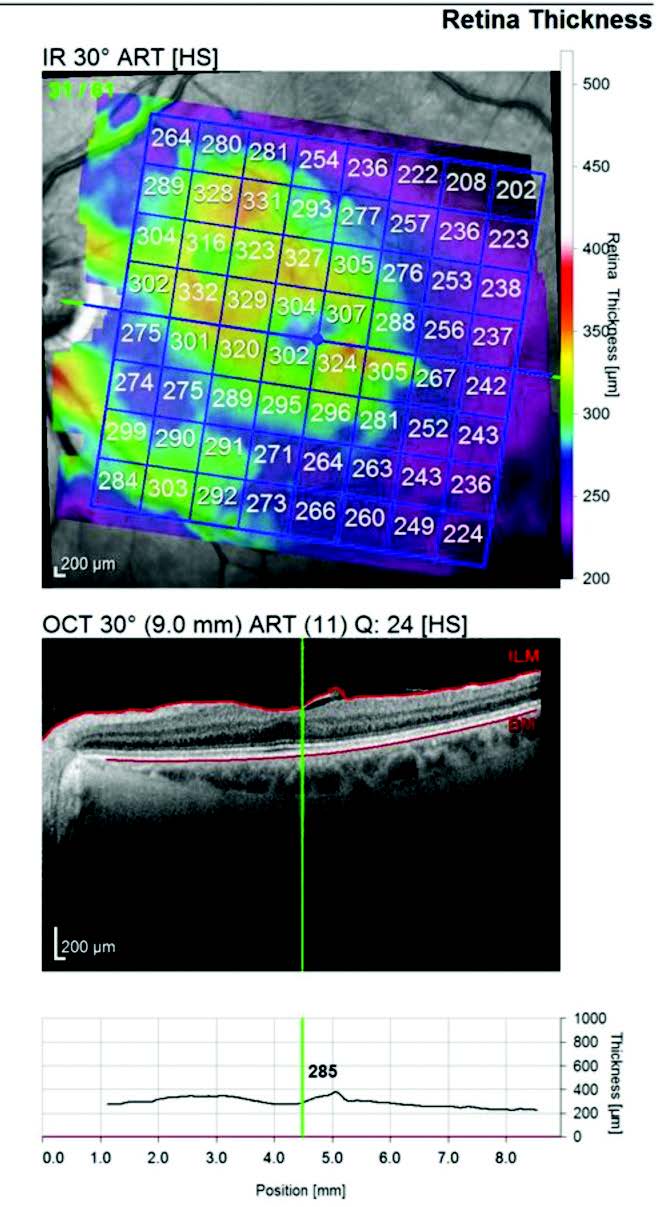

|

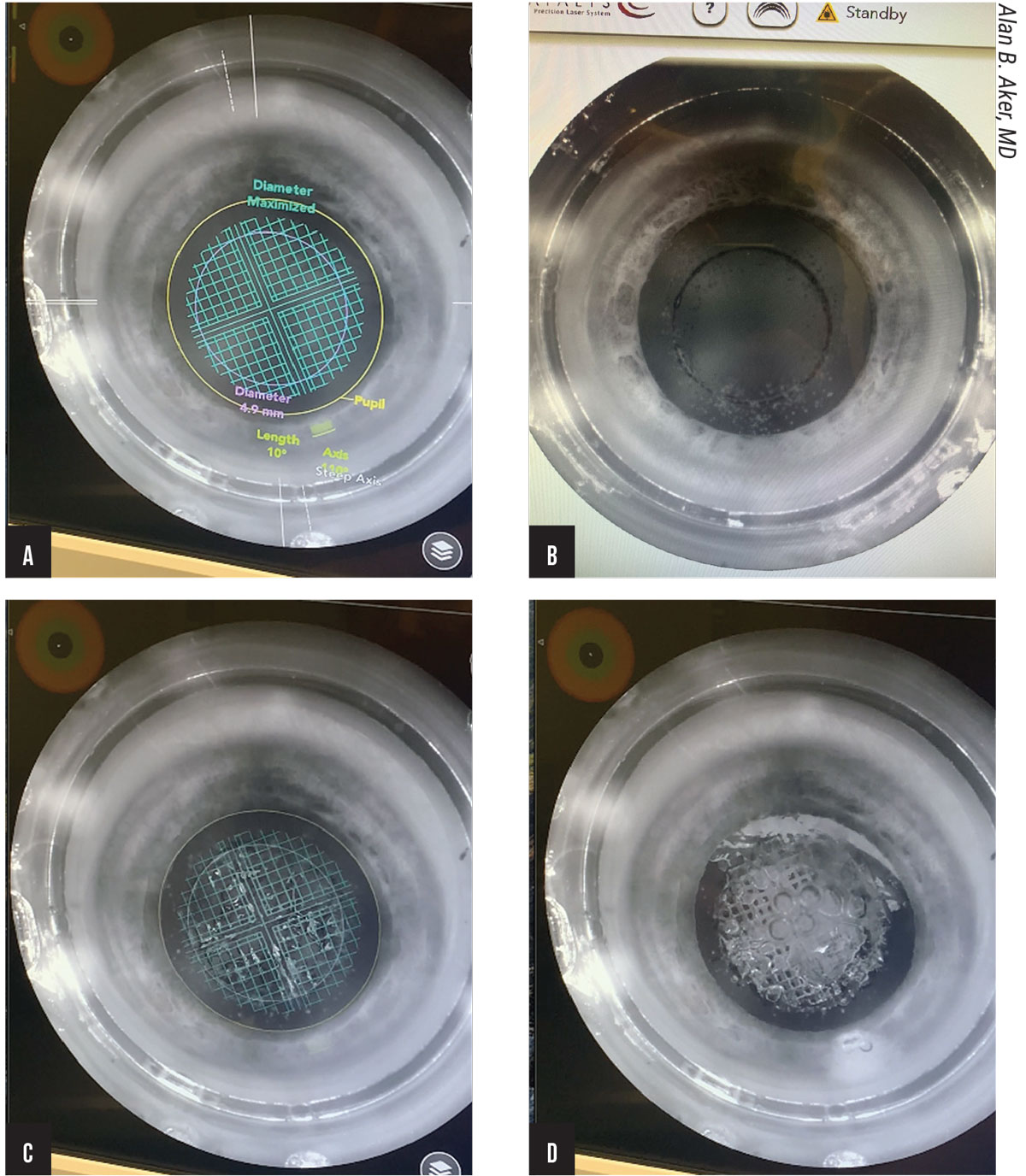

| Figure 4 A-D. When the femtosecond laser is used in cataract surgery, the first step (A) is the establishment of safety limits by the iris perimeter, maximizing the diameter. A perfectly centered capsulorhexis follows, completed in two seconds (B). The waffle pattern on the lens (C) shows one of several laser pulses as it softens the cataract. Fragmentation of the lens generates gas bubbles that help dissect the nucleus of the cataract (D). |

Dr. Greenwood was similarly impressed by the femtosecond laser when he used it at his practice for a limited period. “I learned a lot from it,” he says. “We’re all good cataract surgeons, of course, but we can’t do what a laser can do. It’s more precise.”

Dr. Greenwood used the lessons he learned from femto to create a capsulotomy with sufficient overlap to ensure that it contracted around the optic, leading to better centration and less chance of IOL tilt. “These techniques ensure the superior visual outcomes surgeons are seeking from premium IOLs,” he says. He notes that femto also taught him the visual significance of a half-diopter of astigmatism and the benefits of correcting astigmatism below 1 D, the lowest correction level treated by toric IOLs. “That’s when using the femtosecond laser to create some arcuate incisions was really helpful,” he adds. “With some of the femtosecond platforms, you’re able to use the femto technology for toric IOL markings. I think the femtosecond laser is a very nice tool, and it’s up to individual surgeons to decide whether it’s beneficial for them and their patients or not.”

Why hasn’t he continued with femto? “For a variety of reasons,” he says. “For us, as the IOL and lens technology got better, the benefits that the femtosecond laser were providing us were not as great as some of the hurdles, whether it be cost or inefficiency or technique and things like that.”

He notes that the availability of the Light Adjustable Lens (RxSight), now able to correct very small amounts of astigmatism, has provided another reason the femtosecond technology isn’t always necessary. “For patients who have a very small amount of astigmatism, maybe the toric IOL isn’t appropriate for them, but the Light Adjustable Lens can take care of that need,” he says.

From Doubter to Doer

Dr. Aker says he originally opposed the use of the femtosecond laser because of the challenging financial model it presented. Now he offers it to every patient because he says it provides the best outcomes for the cornea and the capsulorhexis. He recalls realizing one day that he and his partner/wife, Dr. Kasten, were not using the technology correctly. “If this technology provides better, safer surgery, then we should be using it on all patients, not just premium ones,” he reasoned.

He and Dr. Kasten have used an alternative pricing strategy to make femto work in their practice. “We have practices in our area charging $4,500 per premium lens, and we’re at $3,300,” he notes. “Or practices will charge what we charge and add $1,500 for the femtosecond laser. Instead, we now add $300 to our premium lenses across the board and we add $1,500 to the cost of regular cataract surgery for the femtosecond laser. For premium patients, they just see the cost of the lens. And included in that is a femto procedure. If the patient is paying for a premium result, there’s no way I’m going to do a sub-premium cataract procedure for him or her. We use femto to protect the cornea (via the use of less phaco energy), correct less than a diopter of astigmatism and achieve a perfect final lens position.”

Dr. Aker says he explains to patients that he can use his experienced surgeon’s hands to perform a near perfect capsulorhexis, and that he can protect the cornea with viscoelastic solutions. ‘“But I can’t protect your cornea as well as the femtosecond laser does when it softens a cataract,”’ he says.

How to Go Premium

Whether it’s with a femtosecond laser or not, surgeons who’re expanding their premium cataract practices offer some basic advice for you to follow to find out how to do the same in your practice:

• Talk to peers who are doing it;

• consult with IOL and diagnostic technology reps, who are well-versed on how other surgeons are doing it;

• make it your mission to learn what you can at state, regional and national ophthalmology meetings, either from lectures or from colleagues with whom you can network; and

• avoid bad word-of-mouth perceptions of your practice, which can invalidate the sharpest marketing efforts.

“Some doctors need to purchase the diagnostic technology that makes this type of practice possible and some already have the technology, but they don’t understand how to use it yet,” says Dr. Patterson. “It’s like an iPhone. You sometimes don’t really have a clue what technologies are on it until somebody helps you with it. It’s amazing what it can do. You have the technology; you just don’t know how to use it. That same principle applies to lens and device technology.”

Dr. Greenwood recommends that you avoid negative outcomes at all costs. “If you ask patients to pay for a premium intraocular lens, and there’s residual r

eefractive error or they experience less than ideal outcomes, they’re not going to be happy,” he says. “They’re going to tell their friends and other potential patients that they didn’t feel they got any benefit from the premium lenses they paid extra for.” He recommends offering patients a premium “package” price that includes all enhancements such as LASIK, PRK, IOL rotations or a full IOL replacement at no extra charge to ensure patients are completely satisfied.

“Make sure every one of your patients gets into the endzone,” he continues. “Keep your offerings simple. Everyone in your practice–particularly a few key people–needs to be very comfortable discussing financials with the patients. And it’s really helpful if the doctor is one of them, because the doctor is the one introducing the surgery. If the doctor can at least begin to discuss pricing with the patient, that typically is very helpful. You want to provide follow-up for these cases that’s not different from what was outlined in the original plan, whether it’s a second procedure or the possibility of another surgeon needing to do the follow-up because of his or her expertise or role in the practice. Patients are very happy, trusting and encouraged by these approaches. It takes a little time and effort on the front end. But having a plan in place and discussing it with the patient is very helpful.”

Intraprofessional Trust and Support

“I welcome any surgeon who’s interested in getting involved in premium products and services to come visit us,” says Dr. Aker, who will join Dr. Rapp to present their approach to building a premium cataract surgery practice at an upcoming meeting of the Palm Beach County Ophthalmology Society. “Find out how it works and see how we do it. When we share information like this, it benefits all of our practices.”

Dr. Aker is a speaker for Johnson & Johnson Vision and Bausch + Lomb. He also serves as Medical Monitor for the CORD Group. Dr. Patterson is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditech, Bausch + Lomb and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Greenwood is a speaker for Alcon. Dr. Wallace reports no financial relationships with companies that make products mentioned in this article.