|

| Photo courtesy of Getty Images. |

Being an expert witness is a little bit like being a detective. The job requires putting together a picture of what happened with the patient based on chart notes, diagnostic tests, other records and depositions from witnesses and treating physicians. Based on these clues, an expert witness should be able to determine how the patient got from their presenting condition to where they are today—that is, if the documentation is all there.

In this article, I’ll share some pearls that I’ve gleaned from my experience as an expert witness to help you manage risk more effectively and decrease your risk of litigation.

Risk Management Pearls

According to data from OMIC, between 2016 and 2020, there were 299 cataract claims totaling $3.6 million in defense expenses and $8.16 million in indemnity payments.1 Looking more closely at the data, we can see that as the popularity of premium IOLs continued to rise, so did the number of claims in this subset. Ninety-nine of these claims involved premium IOLs and premium services (mean indemnity payment $263,077; range: $3,000 to $1 million).1 While this is a predictable outcome given the out-of-pocket nature of premium IOLs along with increased patient expectations, this doesn’t have to be the case. Surgeons can decrease their risks of litigation by incorporating the following principles into practice:

1. Document everything appropriately. Reducing your risk of litigation involves returning to the basics of risk management. In fact, one of the first steps is making sure you’ve documented everything appropriately. It’s very difficult for an expert witness to defend you if they don’t have a record that reflects the care you actually provided. Best practices for written documentation lays a paper trail that an expert witness can readily follow, and ideally allows them to come to the same conclusions that you had in caring for the patient. Poor documentation, on the other hand, allows the plaintiff’s expert to make a case that you deviated from the standard of care even if that isn’t what really happened.

Best practices also requires the record be accurate, consistent and comprehensive. Your chart should paint a full picture, not just focus on particular aspects of the patient’s ocular condition. Be sure to include all vital history and exam findings, including pertinent negatives, any documents you reviewed and the tests you ordered—anything that allowed you to logically come to your diagnosis.

Anything included in the chart becomes a matter of record. Be especially aware of the copying and pasting feature of EHRs that allows inaccurate information to be transcribed into the record. Any part of the medical record that’s inaccurate creates an avenue for a plaintiff’s medical expert to question whether you were assessing the patient properly. Similarly, if you or a staff member make a note that doesn’t match up anywhere else in the chart, as long as it’s in the chart, it may be used as evidence against you.

2. Be mindful of your language. The wording you use to describe the patient’s complaint and anything else in the chart also matters. Inflammatory words and partial notes out of context may come back to bite you.

Be sure to also communicate this practice to your staff. Both physician and staff should have a mutual understanding of what sort of documentation goes into the chart. Sometimes patients say things off-the-cuff that when documented and read alone create a very different impression than what actually occurred. However, if that’s the only thing written in the chart, it’s accepted as accurate.

3. Never alter anything. As you know, you must never alter medical records. That’s the number-one way physicians get into trouble. You may consult with your insurance carrier if you feel something needs to be added. Most of the time this will be in an addendum that’s signed and dated appropriately. As most malpractice carriers will tell you, the time to add a note to the chart is when the patient is being seen or at their next visit, not when you receive notice that there’s a lawsuit.

4. Review your colleagues’ charts and have them review yours. As a best practice, I’d recommend having a colleague evaluate a chart objectively through the “risk management lens” to identify potential areas of improvement.

Ask them to verify that you’re recording sufficient details that would enable another ophthalmologist to support your clinical decisions. If you’re in a group practice, take one another’s chart every now and then (using a HIPAA-compliant protocol) and ask yourself, “Could I ascertain from this chart that the assessment and treatment were appropriate? That the patient’s issues were taken care of? Does the treatment provided adhere to the standard of care based on the way the patient is presented in the chart?”

5. Try a variety of patient teaching methods. Communication skills are key to mitigating risk. People learn in many different ways, so to ensure your patients have a thorough understanding of premium IOLs and have appropriate expectations, it’s a good idea to supplement your consent discussion with educational handouts, videos and other tools whenever possible. For instance, I routinely use an eye model to give patients a 3D visual of what’s going on in their eye and to help explain potential complications.

Even if your patient doesn’t have any questions, using teach-back methods can help you gauge how much your patient really understands about the treatment and what their expectations are. Staff can also help educate patients by asking them to explain in their own words what their surgical goals are, what they expect their vision to be like postoperatively and how the surgery will affect their daily activities. Patients need to understand the risks, benefits and alternatives to any procedure. At times, patients may dismiss cataract surgery as risk-free because the procedure is outpatient or their friends have had great outcomes. Helping them understand that cataract surgery is a surgery and the inherent risks that are present, especially in regard to IOLs, can make a huge difference. Ensuring that patients have realistic expectations—especially in regard to premium IOLs—is key.

6. Use comprehensive consent forms. Using a patient-specific consent form as opposed to a standard consent form is another important part of your paper trail. If there are specific patient characteristics that are going to affect their final outcome, it’s important to include them on the consent form and make sure that you document the discussion in the chart. Typically, I discuss the risk factors with the patient, document the conversation and add the patient-specific risk factors to the informed consent document along with my signature and their signature: The idea being that if someone were to review this document retrospectively, they’d be able to clearly see that the patient had a particular risk factor present, there was a discussion and education preoperatively about this condition, and the patient was made aware of the potential impact of this risk factor on their final outcome.

7. Discuss and document intraoperative changes. Intraoperative changes that seem to deviate from the original surgical plan are another common cause of lawsuits. Of course, you can and should make intraoperative changes on the fly; just be sure to explain them well to your patient postoperatively and document them accordingly. Have a conversation preoperatively with your patient about the surgical plan, with the caveat that adjustments may need to be made at the time of surgery. Typically, the possibility of intraoperative changes is also included in the written consent form.

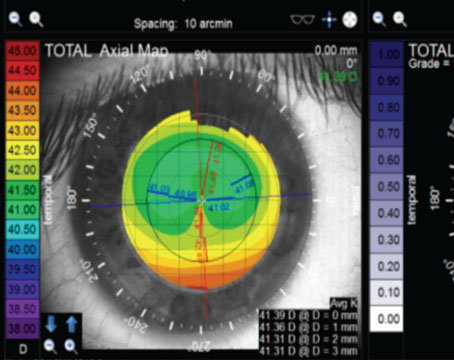

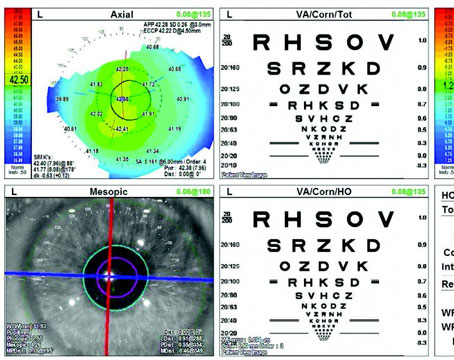

8. Double check your data and measurements. Data transcription errors may occur between the clinic and the ASC. Implanting the wrong lens or the incorrect lens power is another common cause of lawsuits. Avoid this by double checking your measurements, having a consistent system in place and making sure lens verifications are made prior to implantation. It’s also good practice to ensure that your final operative report is not a generic template and accurately reflects each procedure.

9. Clearly document insurance billing and out-of-pocket fees. One universal source of patient discontent occurs when it’s unclear how a premium IOL procedure is billed. Providing the patient with clear information regarding fee breakdown preoperatively is key to mitigating this risk. Maintain a copy in the chart and be sure it clearly states what the patient has already paid or might still need to pay.

10. Promptly disclose and address complications and postoperative sequelae. Patients understand that complications can occur, but what makes most people upset is when communication is poor and they feel that things have been hidden from them, and believe they’ve been abandoned.

The first step is to ensure you’ve had a thorough preoperative discussion about the risks and potential complications of the surgery. When postoperative complications occur, your communication skills and ability to deliver bad news will be key. Speak with compassion, empathy and honesty.

Take your next steps promptly, whether that’s repeat testing or referral, and monitor progress closely. Be open to getting a second opinion or additional help from specialists when necessary and without delay.

11. Be available to your patients. You never want your patient to feel abandoned by you. While it’s natural to want to avoid discussing unpleasant situations such as complications, it’s important to remain accessible to your patients. Even if they’re stable and you may not need to see them for three weeks, these patients may require extra reassurance that only a visit with you can provide. Think of more visits as opportunities for patient education and relationship-building.

Keeping these pearls in mind will help give you an opportunity to focus on good patient care and decrease your risk for litigation.

Dr. Lisa Nijm is a board certified, corneal, cataract and refractive surgeon at Warrenville EyeCare & LASIK, a licensed attorney, and an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at the UIC Eye and Ear Infirmary. She serves on the board of directors for the Cornea Society, AAOE and is the CEO of Women in Ophthalmology. Dr. Nijm is the Chief Medical Advisor for TearLab. She’s created two resources for physicians: MD Negotiation (MDNegotiation.com) to help with negotiation skills; and Real World Ophthalmology (RealWorldOphthalmology.com) to assist young MDs as they start their careers.

1. Harrison L. An updated study of cataract surgery claims. Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company. The Digest 2021;31:1:1-7.