When dealing with glaucoma secondary to intraocular tumors, it’s essential to have a systematic approach. These cases can be complex, often requiring a careful evaluation to differentiate between typical glaucoma causes and those linked to tumors. If there’s a tumor, glaucoma management efforts must be planned with care.

Here, I’ll review the most common types of intraocular tumors that should be on every glaucoma specialist’s radar and discuss the crucial treatment do’s and don’ts.

The First Signs

When assessing a patient, the glaucoma specialist should consider intraocular tumor if the patient has unilateral or refractory glaucoma. It’s essential to rule out a tumor, particularly if there are additional signs such as melanocytosis—pigmentation of the sclera—or if gonioscopy reveals a brown hue in the anterior chamber angle. These features strongly suggest the potential for melanoma. With unilateral glaucoma, it’s crucial to determine the underlying cause, as a small minority of cases may be due to intraocular tumors, which aren’t limited to melanoma alone; other types of intraocular tumors can also lead to glaucoma.

|

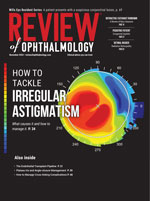

| Figure 1. Autofluorescence and fundus photography showing dense vitreous hemorrhage in an 86-year-old woman with choroidal melanoma with neovascular glaucoma and loss to follow-up for three years. |

Glaucomatous Mechanisms

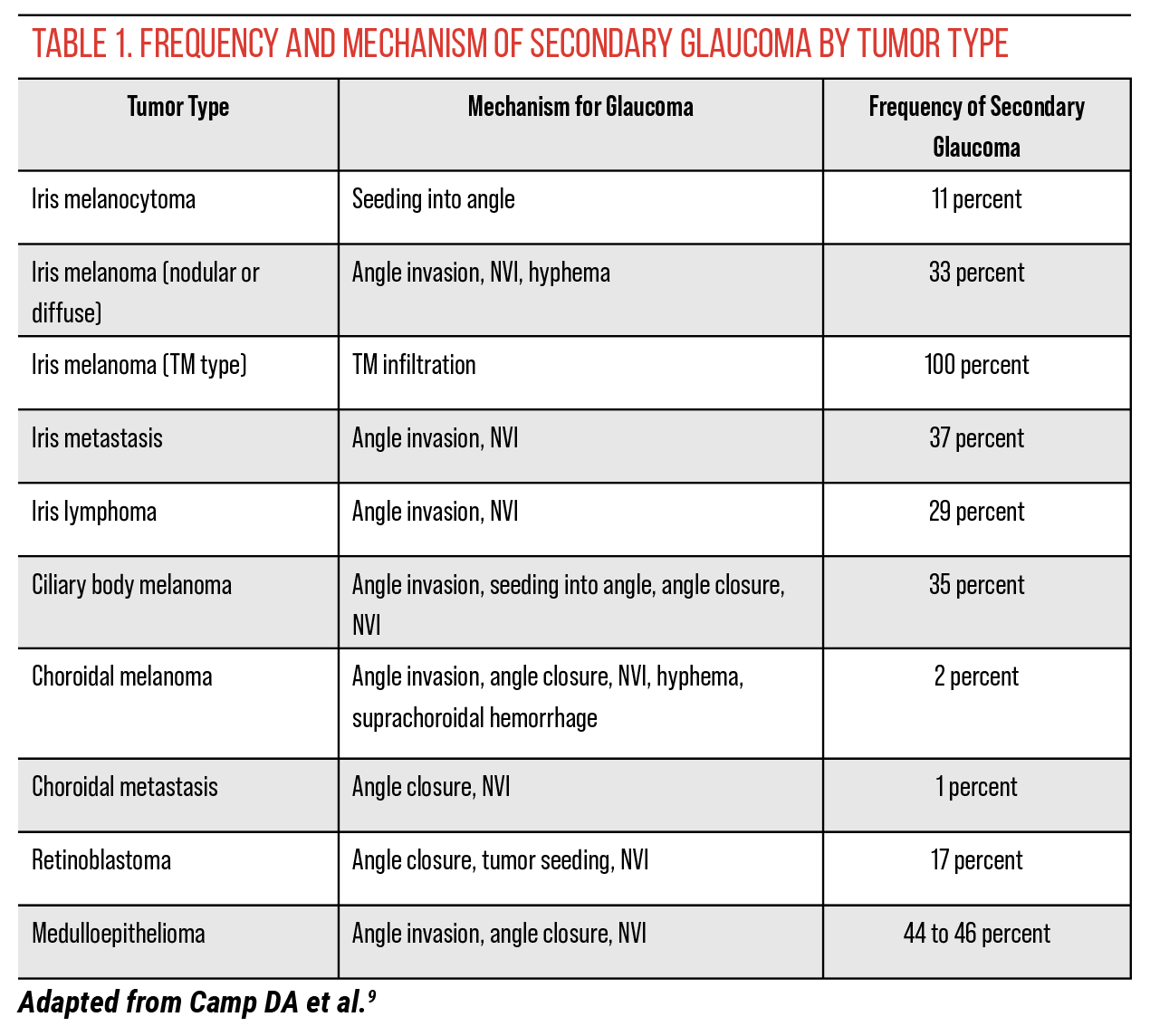

Intraocular tumors can cause glaucoma in a number of ways. One of the most common mechanisms involves angle invasion from the tumor, which can be seen with iris melanoma, ciliary body melanoma that invades the iris or even melanocytoma—a benign tumor that, while not malignant, can drop pigment into the angle, leading to glaucoma. This results in tumor-related open-angle glaucoma.

A second common mechanism is neovascular glaucoma, where the tumor produces excessive VEGF, or in cases of retinal detachment, causes neovascularization of the iris in the anterior segment, which then leads to glaucoma. While neovascular glaucoma is very rare with melanoma or metastasis, it can occur, particularly when a patient has a significant retinal detachment, as the ischemic retina promotes the development of NVI.

Intraocular Tumors

|

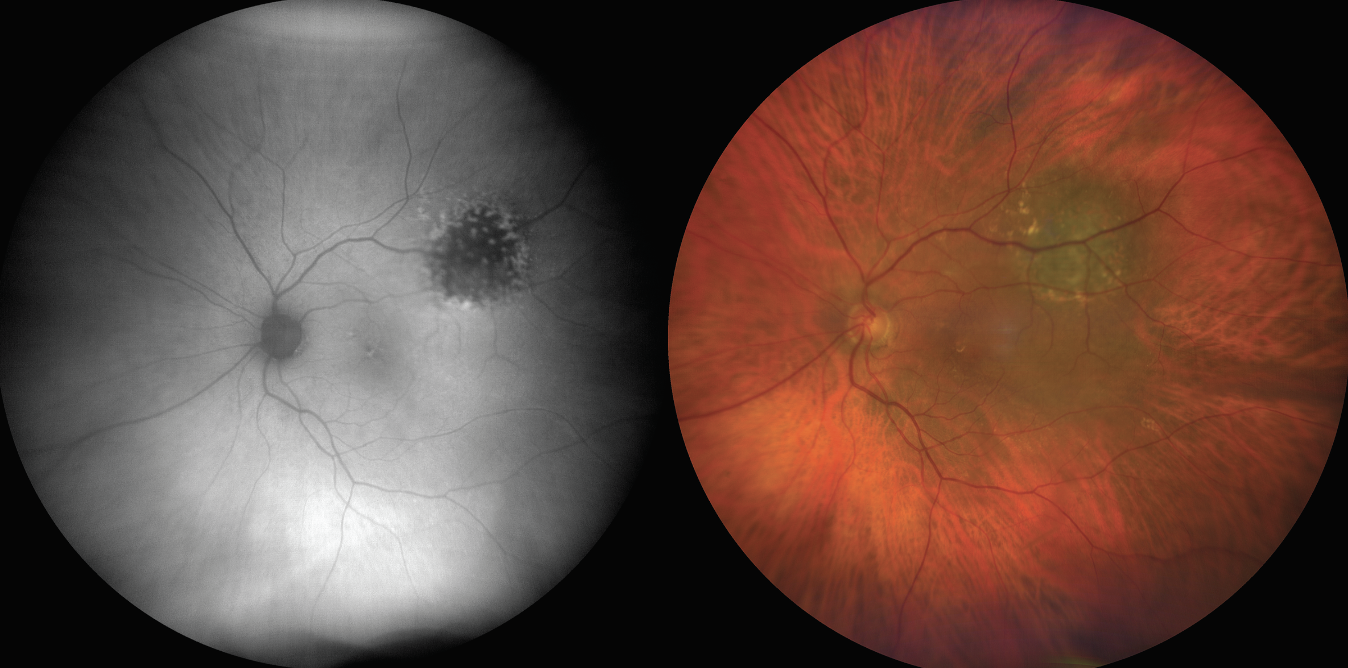

| Figure 2. An external photograph of the same patient from Figure 1, showing iris neovascularization. |

The most common tumors that produce secondary glaucoma are iris melanoma or ciliary body melanoma with angle invasion. Uveal melanomas represent 5 percent of all melanoma (including skin melanoma) diagnosed in the United States.1 Secondary glaucoma has been reported to occur in 33 percent of eyes with iris melanoma, with significantly higher rates in American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification category T4 versus T1.2

It’s crucial not to wait for the patient suspected of having iris melanoma to exhibit extraocular extension; instead, examine the angle for brown pigmentation. If it appears brown, perform an ultrasound biomicroscopy and check the retina with indirect ophthalmoscopy-induced scleral depression to see if there’s any pigmented mass posteriorly. If uncertainty remains, refer the patient to an ocular oncologist, who can perform a fine needle aspiration biopsy to confirm whether the pigmentation in the angle is or isn’t a tumor. We frequently use fine needle aspiration biopsy in our practice.

A specific form of iris melanoma infiltrates the trabecular meshwork. Patients with this type of melanoma typically present with eye pain and elevated intraocular pressure. Upon examining the angle, if it appears chocolate brown, this raises the suspicion of melanoma localized to the trabecular meshwork. At that point, we’d perform a fine needle aspiration biopsy to sample the trabecular meshwork. If melanoma is detected, we proceed to irradiate the entire anterior segment, including the trabecular meshwork and a bit of the ciliary body, to ensure that all affected cells are treated.

In cases of iris metastasis, secondary glaucoma has been reported to occur in 37 percent of eyes.3 Treatment with anti-VEGF agents such as ranibizumab4 and bevacizumab5,6 has shown success in secondary neovascular glaucoma. Iris metastasis manifests as yellow, white or pink nodules in the iris stroma. Hyphema or pseudohypopyon may be present as well, along with poorly defined iris thickening and iridocyclitis.

Ciliary body melanoma, or ring melanoma, as its other name suggests, extends in a ring-like fashion around the ciliary body. It’s often missed on the exam, but there are several diagnostic clues that indicate its presence, including shadow on transillumination, multilobular mass and bulging episcleral veins.7

Melanoma of the choroid has a pigmented, dome or mushroom-shaped appearance. It’s often accompanied by subretinal fluid, orange pigment and exudative retinal detachment. This type of melanoma accounts for 90 percent of all uveal melanomas, and secondary glaucoma occurs in 2 percent of cases.8 Cream-colored or yellow lesions may be indicative of choroidal metastasis. This condition is often associated with serous retinal detachment. Secondary glaucoma occurs in 1 percent of cases.9

|

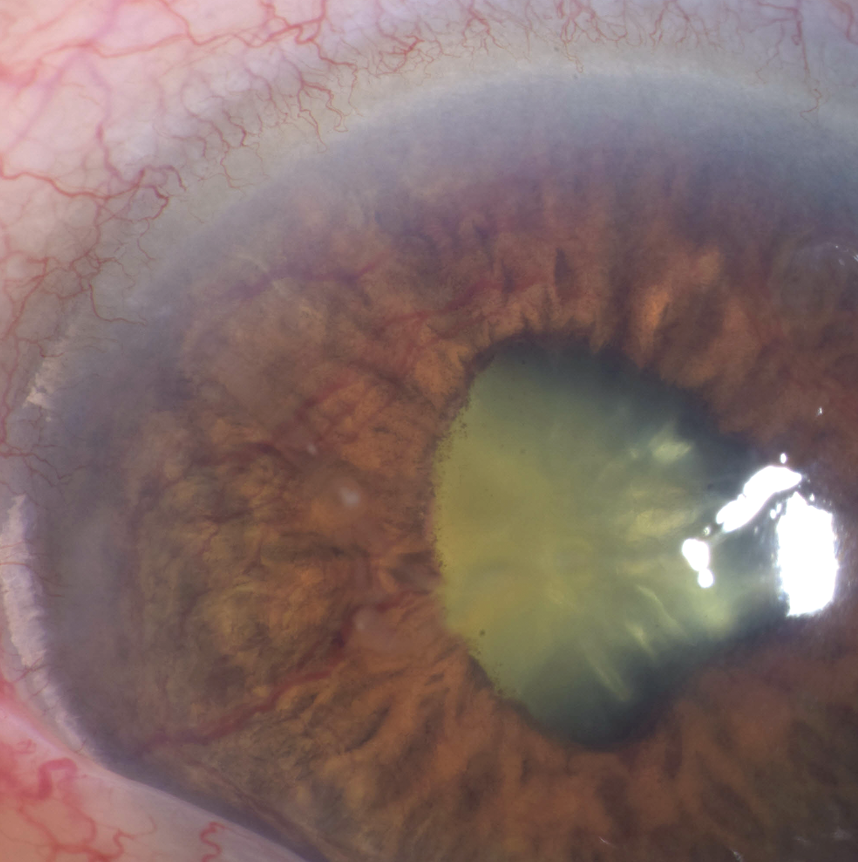

| Figure 3. Ultrasound revealed a large tumor in the patient from Figure 2. Enucleation was performed for this case. |

Retinoblastoma and retinal astrocytic hamartoma can also result in secondary glaucoma.9 Among children, retinoblastoma is the most common malignant intraocular tumor and leads to secondary glaucoma in 17 percent of cases.9 Its white, elevated lesions located in the sensory retina are accompanied by afferent and efferent blood vessels and intratumoral calcification. Retinal astrocytic hamartoma is benign but in rare instances may cause iris neovascularization, leading to secondary glaucoma. It appears as a slightly elevated, transparent or white lesion in the retinal nerve fiber layer.

When evaluating a child with unilateral glaucoma, it’s crucial to check the fundus for retinoblastoma or retinal detachment and to examine the ciliary body for medulloepithelioma, a very rare nonpigmented ciliary epithelial tumor of which we encounter, on average, only two cases per year. These tumors are often misdiagnosed long-term because clinicians may not think to look in the ciliary body. Ultrasound biomicroscopy or anterior segment OCT can help image the ciliary body, especially in cases of neovascular glaucoma. Before inserting a tube shunt or performing any manipulation, a full exam under anesthesia to exclude medulloepithelioma is warranted.

In adults, neovascular glaucoma typically arises from classic conditions like diabetic retinopathy, ocular ischemic syndrome, or central retinal vein obstruction—vasculopathic causes. However, in children presenting with neovascular glaucoma, the suspicion should be for tumors, primarily retinoblastoma or medulloepithelioma, and potentially juvenile xanthogranuloma, which can lead to vascular changes in the iris. This highlights the different focuses in diagnosis: vasculopathic in adults versus tumor-related in children. If you see a child with unilateral neovascular glaucoma, it’s essential to investigate thoroughly; you may not find an ischemic retina, but rather a small ciliary body medulloepithelioma, which can be as tiny as a pea or even smaller, yet still produce extensive neovascular glaucoma with ectropion, making early detection vital.

|

Misdiagnoses

Intraocular tumors can be overlooked in unilateral open-angle glaucoma, though other masqueraders are possible. In one case report, non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the iris masqueraded as uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome.10

Usually, glaucoma specialists are comfortable with gonioscopy and would notice that the angle appears brown in color or irregularly pigmented. If there’s an iris mass, they may consider iris melanoma with seeding.

However, in cases of trabecular meshwork melanoma, general ophthalmologists might diagnose the patient with unilateral glaucoma and start treatment with eye drops. When the glaucoma remains uncontrolled, they may increase the medication or add more drops before eventually referring the patient to a glaucoma specialist. Upon conducting thorough gonioscopy, the specialist might observe that the angle does look brown and then refer the patient to an ocular oncologist. This process can lead to delays of six months or even a year on eye drops while the tumor continues to develop.

I can’t emphasize enough how important UBM is in these cases. We perform UBM by taking images at every clock hour—12 o’clock, 1 o’clock, 2 o’clock, 3 o’clock and so on—to confirm that there’s no solid mass in the ciliary body.

If there’s still a question as to whether or not an intraocular tumor is present, obtaining a good MRI can be very helpful. An MRI will show you a medulloepithelioma, which is often quite small and can still promote neovascular glaucoma. It’s believed that medulloepithelioma releases VEGF, leading to neovascular glaucoma. If you can’t determine the cause, an MRI is warranted. Ensure that thin slices are taken through the globe—both axial and coronal cuts—to thoroughly visualize the ciliary body and confirm that nothing is missed. We typically obtain T1 with fat suppression plus gadolinium, as well as T2 images.

In our practice, we typically see a patient with an intraocular tumor causing glaucoma about once every month or two. The first thing we emphasize in our correspondence to referring doctors is, “Please don’t perform a trabeculectomy, tube shunt, or MIGS,” because we worry that tumor spread through the globe opening could occur. Our approach is to treat the tumor first, then manage with topical drops, and finally consider cyclophotocoagulation. This is about all we can offer the patient, as we want to avoid opening the eye.

Managing Tumor-induced Glaucoma

Is it safe to insert a tube shunt, perform a trabeculectomy or place a MIGS valve in these patients? The answer is yes, it can be done, but the tumor should hopefully be treated first. We avoid any open globe surgery if the patient has iris melanoma, but it’s fine to perform this surgery after treatment of choroidal melanoma in the back of the eye.11 We recommend the first line of treatment for treated iris melanoma be topical drops, and if those fail, cyclophotocoagulation.

Coping with glaucoma secondary to intraocular tumor, especially iris melanoma, is a long and challenging journey for the patient, as we’re unlikely to permit a tube shunt or trabeculectomy due to the risk of seeding the tumor outside the eye. Tumor seeding could lead to more serious complications, including dead or viable tumor in the orbit. For choroidal melanoma, tube shunt or trabeculectomy can be employed after treatment of the melanoma.

This presents a difficult scenario, which is why many patients with glaucoma resulting from an intraocular tumor undergo enucleation. However, if the pressure isn’t excessively high, it’s sometimes possible to manage it effectively while preserving vision. Once the pressure rises to around 45 to 50 mmHg, though, enucleation is necessary, as nothing can effectively lower the pressure if the eye has a tumor infiltrating the angle.

At Wills Eye Hospital, we’ve encountered all sorts of cases where the glaucoma was discovered and the tumor remained hidden. In these cases, if glaucoma surgery is performed before tumor treatment, the conjunctiva might eventually turn black from hidden melanocytoma or melanoma seeding into the subconjunctival space. So again, with unilateral glaucoma, it’s crucial to ensure there’s no underlying tumor.

Missing an intraocular tumor is a fear shared by all glaucoma specialists. To ensure there’s no tumor present, it’s common to refer patients with unilateral glaucoma and unclear causes for further examination, and we’re happy to assist. We conduct a comprehensive examination of both the anterior and posterior segments, performing ultrasound biomicroscopy, anterior segment OCT and even transilluminate the eye to detect any abnormalities in the ciliary body. We also perform a fundus evaluation that includes scleral depression all the way up to the pars plana to make sure we can see everything.

Tumor Management

Intraocular tumors can be addressed in several ways, depending on the specific tumor. Some management options include observation, local resection, plaque radiotherapy, enucleation and systemic chemotherapy.

Years ago, we conducted a study of retinoblastoma and found that about 15 percent of retinoblastomas have NVI. In the past, we would enucleate those eyes, but nowadays we treat them with chemotherapy: The tumor shrinks, the retinal detachment resolves and the NVI disappears. Recently, we had a new pediatric patient with NVI and a large retinoblastoma that we managed with intra-arterial chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, the same approach doesn’t quite apply to melanoma. Most melanoma cases with NVI involve very large tumors that are less responsive to regression from radiotherapy. However, we now have a new drug called darovasertib, which we’re using with large melanomas. This medication is used in a neoadjuvant setting, which means if a patient presents with a large tumor and is heading towards enucleation, we can administer this chemotherapy to shrink the tumor. Our hope is that it will even resolve retinal detachment and neovascular glaucoma. Currently, it’s in Phase II/III (NCT05987332),12 and as of now, glaucoma—or any type of glaucoma—is an exclusion criterion, though NVI is not. But down the road, once it’s hopefully approved by the FDA, we may use it to reduce tumors and resolve NVI. This represents a major breakthrough in ocular oncology.

Co-management

Collaboration and good communication are vital when co-managing a patient with ocular oncology. If we see an iris melanoma, we know our radiotherapy for the tumor might create a cataract. We advise that the cataract should be left alone for at least three years to ensure all tumor activity is under control. This is a key guideline we teach all glaucoma specialists and cataract surgeons.

We don’t permit any open globe procedures—no trabeculectomies, no tube shunts and no MIGS, for patients with iris melanoma. We want to avoid filtering the aqueous into the subconjunctival space, as that could lead to bigger problems such as orbital tumor, access to blood vessels and lymphatics, and from there to potential metastatic disease.

If a tube shunt is inadvertently placed before a tumor is detected, we always remove the eye with the tube shunt in place. This is a rare occurrence; it happens once or twice a year. A patient presents with unilateral glaucoma, and the glaucoma specialist treats it with a tube shunt, only for a tumor to be discovered later. In such cases, we remove the eye and tube shunt as one specimen, and then we walk it to our pathology lab. They section everything—the globe, the tube and the valve—and we also take a sample of the orbit where the valve was to check for any deposition of seeds into the orbit. Most of the time, the results are negative, which is good news. If there’s any doubt, we irradiate the socket.

The Takeaway

Establish your routine for evaluating a patient with unilateral glaucoma. Start with a thorough slit lamp exam and a comprehensive fundus exam to rule out diabetic retinopathy, CRVO, ocular ischemic syndrome or even tumor. Perform gonioscopy to check for pigment in the angle or disinsertion of the iris from its scleral attachment, which could indicate a small melanoma. Don’t forget to get UBM to ensure there’s no ciliary body mass.

By following an organized evaluation, you’ll likely catch most cases and rule out other conditions. However, if you’re still in doubt, get an MRI with gadolinium. This will help confirm that there’s no tumor in the eye. And if you’re still unsure, consult with an ocular oncologist for a thorough evaluation.

Dr. Shields is the director of the Ocular Oncology Service at Wills Eye Hospital, a professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University and a consultant at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. She has no related financial disclosures.

1. Chattopadhyay C, Kim DW, Gombos DS, et al. Uveal melanoma: From diagnosis to treatment and the science in between. Cancer 2016;122:15:2299-2312.

2. Shields CL, Di Nicola M, Bekerman VP, et al. Iris melanoma outcomes based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification (eighth edition) in 432 patients. Ophthalmology 2018; 125:913–923.

3. Shields CL, Kaliki S, Crabtree GS, et al. Iris metastasis from systemic cancer in 104 patients: The 2014 Jerry A. Shields Lecture. Cornea 2015; 34:42–48.

4. Makri OE, Psachoulia C, Exarchou A, Georgakopoulos CD. Intravitreal ranibizumab as palliative therapy for iris metastasis complicated with refractory secondary glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2016;25:e53–e55.

5. Seidman CJ, Finger PT, Silverman JS, Oratz R. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of breast cancer iris metastasis. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2017;11:47–50.

6. Aydin A, Tezel TH. Use of intravitreal bevacizumab for the treatment of secondary glaucoma caused by metastatic iris tumor. J Glaucoma 2018; 7:e113–e116.

7. Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Ring melanoma of the ciliary body: Report on twenty-three patients. Retina 2002;22:698–706.

8. Shields CL, Shields JA, Shields MB, Augsburger JJ. Prevalence and mechanisms of secondary intraocular pressure elevation in eyes with intraocular tumors. Ophthalmology 1987;94:839–846.

9. Camp DA, Yadav P, Dalvin LA, Shields CL. Glaucoma secondary to intraocular tumors: Mechanisms and management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2019;30:2:71-81.

10. Gauthier AC, Nguyen A, Munday WR, et al. Anterior chamber non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the iris masquerading as uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome. Ocul Oncol Pathol 2016; 2:230–233.

11. Kaliki S, Eagle RC, Grossniklaus H, et al. Inadvertent implantation of aqueous tube shunts in glaucomatous eyes with unrecognized intraocular neoplasms: Report of 5 cases. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013; 131:925–928.

12. DE196 (darovasertib) in combination with crizotinib as first-line therapy in metastatic uveal melanoma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05987332. Accessed October 7, 2024.