Because glaucoma is a chronic disease, clinicians use different treatment paradigms to address it depending on its severity, as well as other factors such as how stable the disease is at a given point in time. For many other chronic conditions like heart disease, chronic lung disease and diabetes, the severity of the disease being treated is reflected in the ICD diagnostic codes submitted to Medicare and other insurance companies. That’s even true for some ophthalmic diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, where different ICD codes indicate levels of nonproliferative or proliferative disease.

However, this has never been the case for glaucoma. In fact, glaucoma is the only chronic eye disease that doesn’t currently have some sort of severity levels built into its coding; the codes we’ve used for years make no distinction between early, hardly detectable disease and advanced disease where the patient may soon go blind without heroic treatment. The codes have also failed to provide other key pieces of information about the type of glaucoma being treated.

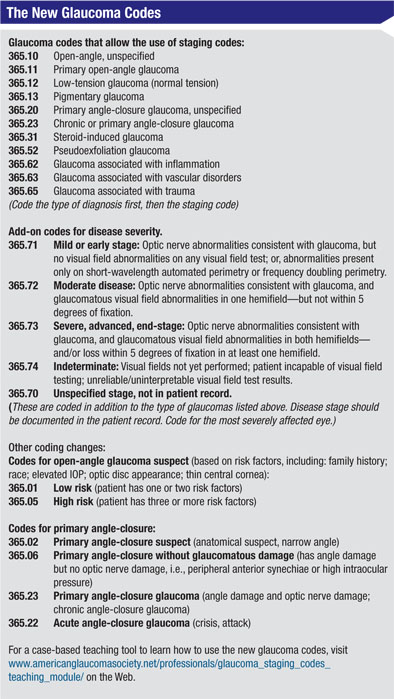

Starting three years ago, doctors began discussing the possibility of changing this by making the glaucoma codes more specific. Since then, revised codes have been developed in consultation with the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Glaucoma Society, with significant input from many experts in the field of glaucoma management, research and coding. In addition to correcting the lack of information regarding disease severity, the new codes also provide more detail about angle-closure glaucoma and glaucoma suspects.

The resulting new codes (see table, p. 54) were included in the AAO Preferred Practice Patterns in 2010, and they’ve been implemented by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as of October 1, 2011. As is usually the case, other insurers are expected to follow suit and adopt the same coding conventions.

Implementing new coding procedures always generates more controversies and problems than anticipated. In this case, physicians’ adoption of the new codes may be hampered by the perceived “hassle factor,” and the fact that the new glaucoma codes aren’t tied to any changes in or requirements for reimbursement—at least for now.

|

One factor that has done a lot to propel the process of developing more detailed codes is the reality of physician profiling. Insurance companies are increasingly comparing doctors and practices as a way to provide a rationale for dropping or curtailing access to physicians who appear to be providing more expensive treatment. This should be of particular concern to physicians who treat glaucoma be-cause glaucoma care has the highest variation in cost of treating of any ophthalmic disease. Furthermore, it’s one of the 20 diagnostic groups most scrutinized by CMS.

In physician profiling, an insurance company looks at your practice and how much your services are costing the company; it compares you to your “peers,” a group that includes all eye-care practitioners and doesn’t distinguish among specialties. If your costs seem higher than other doctors’ costs, the company can say, “The care you provide is too expensive, we’re going to make patients who want to see you have to pay more out of pocket.” At the extreme, the insurer may take you off of its insurance product panel, eliminating all access to its patients. Glaucoma specialists performing large numbers of surgical procedures are particularly vulnerable, due to their complex, higher-cost patient mix. Glaucoma specialists may find that they’re not able to take care of the very patients who need them most. This can also cause problems for referring physicians, who then have to fight with an insurer to get the patient to an appropriate specialist. Utilizing the new staging codes should help differentiate practice complexity and provide a defense if a specialist is unfairly profiled.

The practice of physician profiling has been widespread in the private insurance markets, but most physicians are unaware that it’s happening. Meanwhile, while more and more data about practices and physicians is generated, the technology to track it keeps improving and the economic pressure on insurance companies to pay out less money keeps increasing. New “limited panel,” “value-oriented” insurance products are marketed to cash-strapped employers at alarming rates. Furthermore, Medicare has an enormous supply of existing data that hasn’t been analyzed. Medicare doesn’t profile physicians—yet—but the computer algorithms to do so are in the works. CMS has started profiling some primary-care physician groups already and will start profiling all doctors by 2014.

In short, we haven’t seen anything yet.

Given the increasing movement toward physician profiling, it’s clear that providing accurate information about the nature of your treatment is crucial if you want to avoid being unfairly penalized by insurers. All costs for medications, diagnostic tests, office visits and surgical procedures for a given patient or a given physician will be grouped together by insurers to determine the cost of care. Obviously, taking care of more advanced glaucoma patients will require more resources.

Implementing the new glaucoma codes is a logical way to avoid be-ing penalized for providing more advanced, complex and costly treat-ment when it’s necessary, and to show that cost-effective care is being provided at all stages of disease.

Other Benefits

Having more information contained in the codes could have enormous benefits for glaucoma research as well. Medicare data represents a huge bank of information, drawn from a far larger patient sample than even most well-known multicenter studies. For example, we still don’t know for sure whether some treatments are more effective than others at different levels of disease severity. In the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study, some patients with disease above a certain severity level did better if they had surgery at the time of initial diagnosis, or shortly thereafter, than if they had medical treatment. However, that was a relatively confined medical trial. It would be very helpful to be able to confirm that in a large population such as that served by Medicare.

These kinds of retrospective analyses could become possible with the new diagnostic codes. If they’re widely adopted, the Medicare data-base will provide reams of data tied to disease severity from large numbers of patients. We’ll be able to look at Medicare-generated billing data and differentiate between the effectiveness of using a laser, surgery or medicines at different levels of disease.

Using the codes will also allow you to analyze resource use in your own practice. If you’re able to personally “profile” your practice mix and anticipate your typical resource use for various stages of disease, you’ll be able to make intelligent decisions about equipment purchases and personnel allocation. You may also be able to track trends in your practice that benefit patient care routines and outreach efforts.

| Value-based purchasing by CMS and performance-oriented evaluation by insurers is on its way. In the final analysis, implementing the new codes stands to benefit us all. The dangers involved with doing nothing are real, and the potential benefits of acting now are significant. |

The real problems that are likely to arise with making this change have to do with whether or not clinicians will choose to actually use the new codes, which are not currently mandatory.

Concerns include:

• There’s no current financial benefit. Some clinicians have ex-pressed hesitation about adopting the new codes because the different levels of severity reflected in the new codes are not tied to different payments—at least so far. As a result, many clinicians see incorporating the codes as a burden with no compensation for the extra effort incorporating them will require.

Ophthalmologists frequently ask why they should bother with the new codes, given that there’s no financial incentive. The answer is that physician profiling is a real problem; it’s happening a lot more than many doctors realize. One day soon you may get a letter from an insurer telling you you’ve been kicked off its board. Or you may notice that company X’s patient volume is declining be-cause patients now have a higher copay to see you, so they’re skipping appointments. Now is the time to take steps to make sure these scenarios don’t happen.

• The potential for abuse. Some ophthalmologists are worried that when the new codes are eventually tied to greater reimbursement, it will create a temptation for doctors to upcode. It goes without saying that inaccurate coding would undercut any benefits that might accrue from the new system. Not only would upcoding shift higher payments to doctors performing less-expensive treatment, it would nullify the usefulness of the resulting data pool—leading to confusion about the effectiveness of treatments.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy answer to this potential problem. Given the advantages of using the new codes, we can only trust that the vast majority of doctors will resist the temptation to upcode. In any case, given the straightforward nature of the staging system, it will be relatively easy for insurers and CMS to audit.

• The insurance companies’ response. Another concern some doctors have expressed is that the insurance companies are unlikely to increase payments to those who are treating more advanced glaucoma (which will be evident with the new codes). Instead, they’re likely to use the severity scale as a justification for reallocating the existing pool of reimbursement funds—which could result in a decrease in payments to those providing simpler services to less-advanced glaucoma patients. Given the economic climate, such a scenario is not out of the question.

Despite these concerns, we can’t afford to sit back and do nothing. If we do nothing, reimbursement cuts will simply continue to occur without any regard for the realities of different glaucoma treatments. Physicians should be cognizant that reimbursement for all care is going to decline in the coming years, with or without the new codes; adapting our practice patterns and resource use to increase efficiency will be necessary.

ICD-10 and the Future of Glaucoma Codes

The new staging codes will be incorporated into ICD-10, which is due to implement in October 2013. ICD-10 has already been delayed several times in the United States, although it’s now the standard in the rest of the world. Despite some bad press, the requirement to be compliant with HIPAA 5010 regulations by January 2012 has laid the groundwork, the billing vendors have geared up and it’s extremely unlikely that there will be any further delays.

ICD-10 will not only include the new staging code system, it will introduce laterality, to further specify the eye that’s affected and the degree to which it’s affected.

If We Do Nothing …

Value-based purchasing by CMS and performance-oriented evaluation by insurers is on its way. Physicians who do not report on or meet quality measures, or who cost more than their peers, will be penalized with lower reimbursements. CMS plans to address conditions involving high variability of care costs with the value-based modifier in 2015. Using these codes is one way to defend the value of our services for glaucoma patients.

In the final analysis, implementing the new codes stands to benefit us all. The dangers involved with doing nothing are real, and the potential benefits of acting now are significant.

Dr. Reynolds is a glaucoma subspecialist in private practice in Boise, and sub-committee chair for coding and terminology for the American Glaucoma Society. Dr. Mattox is director of the Glaucoma and Cataract Service at New England Eye Center, Tufts University in Boston, where she is also a vice-chair of the department. She is chair of the Patient Care Committee for the American Glaucoma Society, and a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Health Policy Committee.