We’ve all been taught not to discuss certain topics around the dinner table—such as religion, politics and money—and if you find yourself breaking bread with glaucoma specialists, you might add selective laser trabeculoplasty vs. medication to that list. It always seems to spark a debate on which treatment method works best for newly diagnosed glaucoma patients and if or how SLT makes an impact when used after drops. However, as more time passes and more data become available, laser proponents say that SLT’s doubters have less ground to stand on. We spoke with several glaucoma experts who say the discourse around SLT is changing and why education is integral to ending the debate.

SLT’s Place in the Treatment Paradigm

In order for SLT to hold a candle to drops for the initial treatment of primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension, doctors needed to see compelling data.

Some small studies have been done examining SLT as a monotherapy, such as the West Indies Glaucoma Laser Study,1 which showed significant and safe IOP reduction in Afro-Caribbean eyes with POAG. However, the 12-month study subjects had previously taken IOP-lowering medications and underwent SLT after washout. Other studies examined SLT’s efficacy on patients who were currently on medications. A retrospective study in a Thai population2 showed SLT decreased IOP, as well as reduced the amount of antiglaucoma drugs needed post laser over a 24-month follow-up period.

But it was the LiGHT trial (laser in glaucoma and ocular hypertension) that really put SLT on the map as a valid first-line treatment. “The LiGHT study was revolutionary,” says Tony Realini, MD, MPH, a professor of ophthalmology and glaucoma fellowship director at West Virginia University who was also involved in the LiGHT trial. “It was the first prospective, randomized study that was actually designed and completed to compare a primary medical to SLT therapy, and it showed that SLT is at least as good as and maybe better than medications in terms of long-term disease control. There was less progression. There were fewer trabeculectomies and fewer cataract surgeries in the eyes that were assigned to laser first as opposed to medications first.”

The LiGHT trial first released its results in 2019 showing 36 months of data. It demonstrated that SLT provided drop-free IOP control in 74.2 percent of patients3 when used as the primary treatment method. Disease progression was also lower in the SLT-first group (3.8 percent of patients) vs. the eye-drops group (5.8 percent).

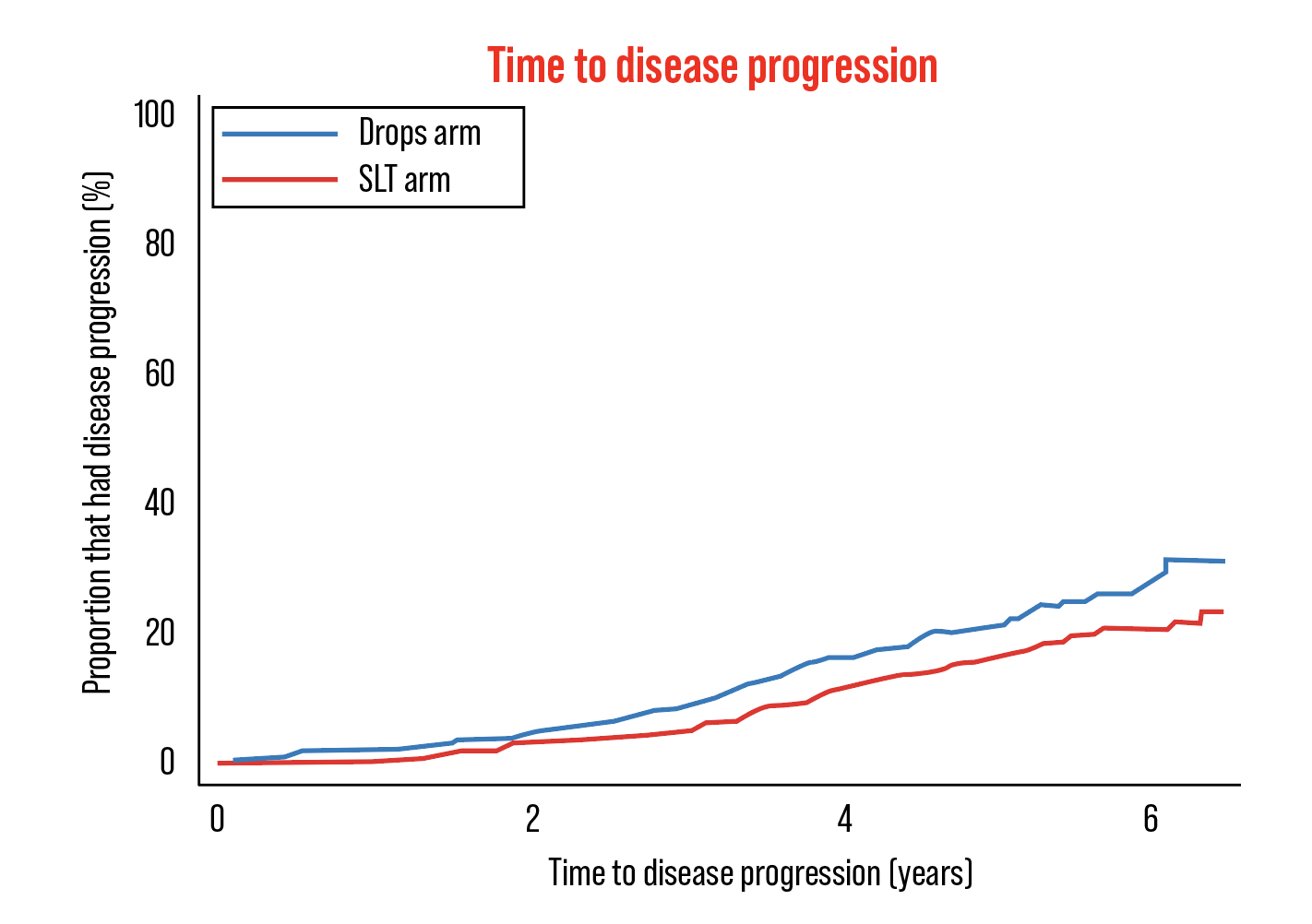

|

| Figure 1. Six-year data from the LiGHT trial indicated statistically significant lower rates of disease progression in eyes treated with SLT as first-line therapy.4 |

In early 2023, six-year data from the LiGHT trial was released, strengthening the case for SLT as first-line therapy. The SLT arm showed better Glaucoma Symptom Scale scores than the drops arm (83.6 ±18.1 vs. 81.3 ±17.3, respectively).4 Of eyes in the SLT arm, 69.8 percent remained at or below the target IOP without the need for medical or surgical treatment. More eyes in the drops arm exhibited disease progression (26.8 percent vs. 19.6 percent, respectively; p=0.006). Trabeculectomy was required in 32 eyes in the drops arm compared with 13 eyes in the SLT arm (p<0.001); more cataract surgeries occurred in the drops arm (95 compared with 57 eyes; p=0.03).

Many in the glaucoma specialty feel this data should instill confidence in performing SLT first-line. “This tide of not using SLT as a first-line treatment is getting smaller and smaller because the data has been, at this point, pretty compelling about offering it as a first-line treatment,” says Carina Torres Sanvicente, MD, an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and glaucoma specialist at the school’s Jones Eye Institute. “We now have six-year data from the LiGHT trial and it still favors SLT. It works better if it’s done before other medications. We actually see a good response for about a year to two years and then it starts to decrease and sometimes we have to repeat it. If I find that the treatment worked well at first but the effect didn’t last long, I like to wait about a year or so for repeat SLT, but there’s data out there that SLT can be repeated fairly quickly after with good safety.”

Repeatability had been a concern of Dr. Realini’s. “When SLT first came out, there wasn’t a lot of evidence and it took about eight years before there was any data at all on repeatability of SLT,” he says. “ALT (argon laser trabeculoplasty) never caught on because it wasn’t repeatable, it was just a stopgap measure, much in the way Durysta has become as well. You’re not going to get much traction on something that is one and done. So there’s been a flurry of data on repeatability of SLT and I started realizing this could be a really effective first-line therapy because when it wears off, we can do it again, and maybe again and help people avoid medications for several years.”

ALT involved collateral thermal damage, leading to subsequent trabecular-meshwork scarring and, when repeated, could cause peripheral anterior synechiae.5 Alternatively, SLT does less damage to the adjacent cells and tissues in the trabecular meshwork.

Dr. Realini, who conducted the aforementioned West Indies Glaucoma Laser Study, says 60 percent of those patients maintained IOP control at the eight-year mark after a single SLT with no need for medical therapy. He’s conducting a new study, the COAST trial (Clarifying the Optimal Application of SLT Therapy), to explore the role of low-energy SLT repeated annually as a means of further extending medication-free survival beyond the current standard, which is standard energy SLT repeated as needed when its effect wears off.

“The advantage of this would be that, if we’re doing less damage to the meshwork by using low-energy SLT, and we’re doing it every year, whether the meshwork has become re-impaired or not, we’re effectively practicing trabecular meshwork health maintenance and the hope is that medication-free survival will be much longer in the low-energy annual group compared to the standard energy PRN group,” Dr. Realini says. “People who are getting SLT have a dual hit to the meshwork: the SLT does damage and the glaucoma does damage. If we can reduce the amount of damage that SLT does by turning down the energy and if we can keep the meshwork healthy rather than trying to rescue it every time it becomes re-impaired by glaucoma, then we may be able to extend medication-free survival over the current standards.”

The doctors we spoke with also believe there should be no hesitation to use SLT as a second- or even third-line treatment.

“If a patient wanted to use drops first and wasn’t where I wanted them to be after two or three months, then I’ll perform SLT, and that makes a lot of sense to me,” says I. Paul Singh, MD, president of The Eye Centers of Racine & Kenosha in Wisconsin. “Or, if the patient was on PGA for years and you thought they were doing well, but you realize they’re still progressing even though the pressures may be ‘at target,’ that may mean compliance is likely an issue with potential for fluctuating IOP. This is a good person to switch over to SLT. It’s a good second-line agent if you’re not comfortable with it as first-line, but it’s not ideal to wait to use it as a last resort.”

Dr. Singh says doctors’ hesitation to use SLT earlier in the treatment paradigm contributed to its reputation in the field as being more modest in terms of efficacy. “I think what we’re seeing is that it’s not just about the number of drops, but when you wait too long, it’s also about disease state. A lot of times the reason why SLT and laser in general got a bad rap is because a lot of doctors were waiting to perform SLT as a last resort before traditional glaucoma surgery,” he says.

“For instance, if someone’s been on drops for years and years but they’re getting worse and the doctor doesn’t want to do a trab yet, they’ll go ahead and try ALT or SLT. That’s a patient whose outflow system is probably diseased not just at the level of a trabecular meshwork where SLT primarily works, but also distal to that (the canal or even distal collector channels). The longer we wait, the more likely the disease of stiffness and fibrosis is occurring at multiple levels, thus limiting the effectiveness of SLT. It’s a catch-22—if you wait too long, you may not have the efficacy you want and that’s why, for me, it’s less about the number of drops in first-line, second-line and third-line, and more about where in the disease stage you’re using it,” Dr. Singh continues.

SLT is a great option to reduce the number of medications a patient may be taking, adds Dr. Realini. “Most of the patients that I’m diagnosing with glaucoma are getting primary SLT, but I frequently see patients who are referred to me who are on medication and I will encourage them to have SLT to get off that medication,” he says. “There’s about an 80 to 90 percent success rate in doing that based on the published literature, and people are happier when they stop drops. You can ask them if their drop is bothering them and they’ll say ‘No.’ But once you’ve done a laser and they come off the drops, the next time you see them, it’s like, ‘Oh my god, my eyes feel so much better.’ They just don’t appreciate how negatively impactful drops are until they stop them.”

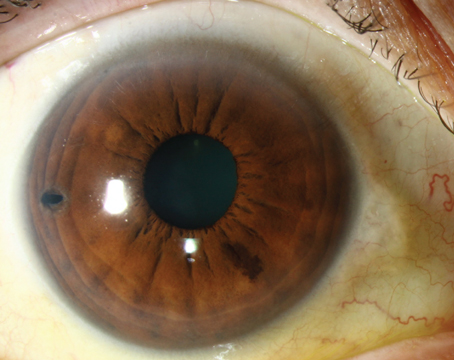

|

| Although patients may initially hesitate to undergo SLT, research shows that proper education about the procedure’s safety and efficacy makes them more likely to adopt it. (Courtesy Carina Torres Sanvicente, MD) |

Shifting the Mindset of Patients and Physicians

Lack of education and understanding has contributed to the slow adoption of SLT as first-line. For the majority of people, drops have been the recommended standard of care and that’s what they expect to be prescribed.

“I tell patients that we can do a quick five-minute, in-office procedure that doesn’t hurt or they can put drops in every day for the rest of their lives, maybe two or three times a day, sometimes two or three drops two or three times a day, which they might not always comply with and is a hassle,” says Dr. Realini.

Doctors are also sometimes hesitant about the “laser,” and assume drops have no risks. “It’s important to recognize that drops are not benign,” Dr. Singh notes. “There’s enough data now supporting how ocular surface disease is a significant disease associated with topical medications. Drops can cause significant meibomian gland dysfunction and significant disruptions of the tear film, which results in symptoms such as tearing, burning, pain, redness, photophobia and fluctuating vision.”

Dr. Singh cites research done by Christophe Baudouin, MD, which showed how ocular surface disease severity contributed to patient adherence to treatment.6 “Baudouin’s study showed us a 30-percent reduction of compliance if you have a prominent ocular surface disease. Compliance no doubt is directly tied to symptomology of dry eye,” he says.

Dr. Realini says there’s a disconnect between what doctors would do for themselves and what they offer patients, and that education is the key to shifting patient expectations. “I gave a talk a couple of weeks ago and I asked, ‘How many in the room would want SLT first?’ All the hands went up,” he says. “Then I asked, ‘How many of you are now routinely performing SLT on the majority of your newly diagnosed glaucoma patients?’ None of the hands went up. I asked, ‘Why is that? Why is it that you’re not taking care of your patients the way you’d want to be taken care of?’ And a voice in the back said the magic words for me: ‘Patients don’t want laser.’ I believe that’s because they’re not talking to them about it correctly.

“As long as we keep offering SLT as an alternative to medications rather than recommending it to our patients as the preferred treatment instead of medications, the paradigm shift is going to languish,” Dr. Realini continues. “Once doctors become comfortable enough to communicate to their patients that this is the preferred therapy, it’s better than medications, then patients will begin to accept it more.”

Dr. Sanvicente studied this very topic.7 “We actually looked at physician beliefs and attitudes and the patients’ beliefs and attitudes back in 2018 and we found that there was some reluctance in about half of the physicians offering it as first-line, with patient uptake being very low. We found that with increased awareness and education regarding the subject of SLT, more physicians seem to be convinced,” she says.

A few years later, Dr. Sanvicente published another study specifically about patient response to SLT education.8 “For patients, we showed them a slideshow and video and more patients underwent SLT after having that intervention,” she says. “There are some misconceptions about laser in general from the patient side, that lasers might blind them for example. We’re able to address those and show it’s safe compared to medications.”

“I have about a 95 to 98 percent laser-first acceptance rate in my practice, because I’ve found a way of talking to patients about SLT that helps them see the benefits that I see,” Dr. Realini says. “I’m not at all hesitant to share with patients that it would be my first-line therapy if those were my eyes. Most patients then would want the treatment that the doctor would want for himself.”

Dr. Singh uses a visual analogy to help. “When I present SLT, I describe the eye as a water balloon and the eye has to make fluid to get the shape of that water balloon, but that fluid has to drain out of the balloon so it can make more fluid,” he says. “I tell them their drain isn’t working, but we can use a beam of light that stimulates their drain to release their own natural enzymes to rejuvenate the drain. The patient is doing all the work naturally. It’s covered by insurance. It’s not invasive, and because it’s nondestructive, we can repeat it again if the pressure goes back up.”

Patient Selection and Risks

Dr. Sanvicente says SLT candidates should have an open and visible trabecular meshwork. “I would avoid any type of secondary glaucoma, such as neovascular glaucoma. I would avoid anything that’s blocking your view from the angle,” she says. “I would say in steroid-response glaucoma, when they’re taking steroids for diabetic macular edema, for instance, they can respond well to SLT, but if they’re on steroids because they have uveitis then I would personally avoid SLT. You also want a patient who understands the goal of the procedure and that it’s not going to improve their vision, it’s going to prevent it from getting worse.”

She also avoids SLT in patients with a low starting pressure. “If your patient needs the pressure in the single digits, or their starting pressure is in the mid-to-low teens (15 or lower), then I don’t think SLT alone will bring that pressure to your target and you might need extra drops anyway,” Dr. Sanvicente says. “So, I avoid SLT in patients with a low starting pressure in the mid-teens and I would consider something else. A pressure in the mid-20s is usually where SLT works best.”

As with anything, there are risks. “There’s a small risk of the pressure going up instead of down,” she continues. “Very rarely that can happen and sometimes it’s immediate, within the hour while they’re being observed in the office, but it’s usually short-lived and we can treat it with medication such as drops or acetazolamide. There’s some risk of eye inflammation that can blur their vision for a little bit and sometimes they need treatment, also rare. Some people have reported a risk of corneal edema, but that’s also short-lived. I haven’t seen that personally.”

Ultimately, Dr. Singh believes it’s time to rethink the traditional linear method of treating glaucoma. “As a profession we need to get away from this whole linear progression of our treatment options and move to a more circular model, where we have a patient centric focus and we’re drawing from all these different modalities for that patient, depending on their circumstance,” he says. “I think we’re also appreciating the mechanism of action. With conventional outflow MIGS such as the stenting, canaloplasty and goniotomy, and the new drops that have come out in the last few years, such as latanoprostene bunod and netarsudil, which work on improving outflow through the conventional pathway, mechanism of action makes a difference. The earlier we address the pathology, the better chance we have of not only preventing it from progressing but also improving our chances of having better efficacy when the entire pathway isn’t completely fibrosed.”

So, is the debate settled? “I personally don’t think it’s a debate,” Dr. Singh concludes. “To me, you can only have a debate when the data is inconclusive. This data from multiple trials is clear and has been clear for years."

Drs. Sanvicente and Realini report no disclosures. Dr. Singh is a speaker and consultant for Ellex Quantel, Glaukos, Alcon, Sight Sciences, New World Medical and NovaEye.

1. Realini T, Shillingford-Ricketts H, Burt D, Balasubramani GK. West Indies Glaucoma Laser Study (WIGLS): 12-month efficacy of selective laser trabeculoplasty in Afro-Caribbeans with glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;184:28-33.

2. Funarunart P, Treesit I. Outcome after selective laser trabeculoplasty for glaucoma treatment in a Thai population. Clin Ophthalmol 2021;18:15:1193-1200.

3. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, Garg A, Vickerstaff V, Hunter R, Ambler G, Bunce C, Wormald R, Nathwani N, Barton K, Rubin G, Buszewicz M; LiGHT Trial Study Group. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;13:393:10180:1505-1516.

4. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, Adeleke M, Vickerstaff V, Ambler G, Hunter R, Bunce C, Nathwani N, Barton K; LiGHT Trial Study Group. Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) trial: Six-year results of primary selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology 2023;130:2:139-151.

5. Latina MA, Park C. Selective targeting of trabecular meshwork cells: In vitro studies of pulsed and CW laser interactions. Exp Eye Res 1995;60:4:359-71.

6. Baudouin C, Renard JP, Nordmann JP, Denis P, Lachkar Y, Sellem E, Rouland JF, Jeanbat V, Bouée S. Prevalence and risk factors for ocular surface disease among patients treated over the long term for glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Eur J Ophthalmol 2012;11:0.

7. Bonafede L, Sanvicente CT, Hark LA, Tran J, Tran E, Zhang Q, Costello R, Myers JS, Katz LJ. Beliefs and attitudes of ophthalmologists regarding SLT as first line therapy for glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2020;29:10:851-856.

8. Tran E, Sanvicente C, Hark LA, Myers JS, Zhang Q, Shiuey EJ, Tran J, Bonafede L, Hamershock RA, Withers C, Katz LJ. Educational intervention to adopt selective laser trabeculoplasty as first-line glaucoma treatment: Randomized controlled trial: Educational intervention on selective laser trabeculoplasty. Eur J Ophthalmol 2022;32:3:1538-1546.