Presentation

An 81-year-old female with decreasing vision and photophobia referred by her outside glaucoma specialist to Wills Eye Hospital for evaluation of bilateral anterior uveitis.

History

Past ocular history was notable for herpetic keratitis of the right eye and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma of both eyes (with placement of Xen gel stent OD with mitomycin-C in 2021). She also had a remote history of central retinal vein occlusion in the left eye. Past medical history included hypertension and diabetes; other past surgical history was non-contributory. Medications included dorzolamide-timolol three times daily in the right eye (and two times daily in the left), brimonidine twice daily in the right eye, latanoprost at bedtime in the right eye and prednisolone acetate once daily in the right eye. She also took a daily multivitamin. Family history was non-contributory. She was a non-smoker with occasional alcohol use. Allergies include cephalexin (blisters) and levofloxacin (skin rash); sensitivities included gluten and lactose. Of note, she shared a history of an unknown reaction to oral moxifloxacin in 2010 that required chronic steroid therapy. Review of systems was negative for scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, fever and loss of appetite; other systemic review of systems was also negative.

|

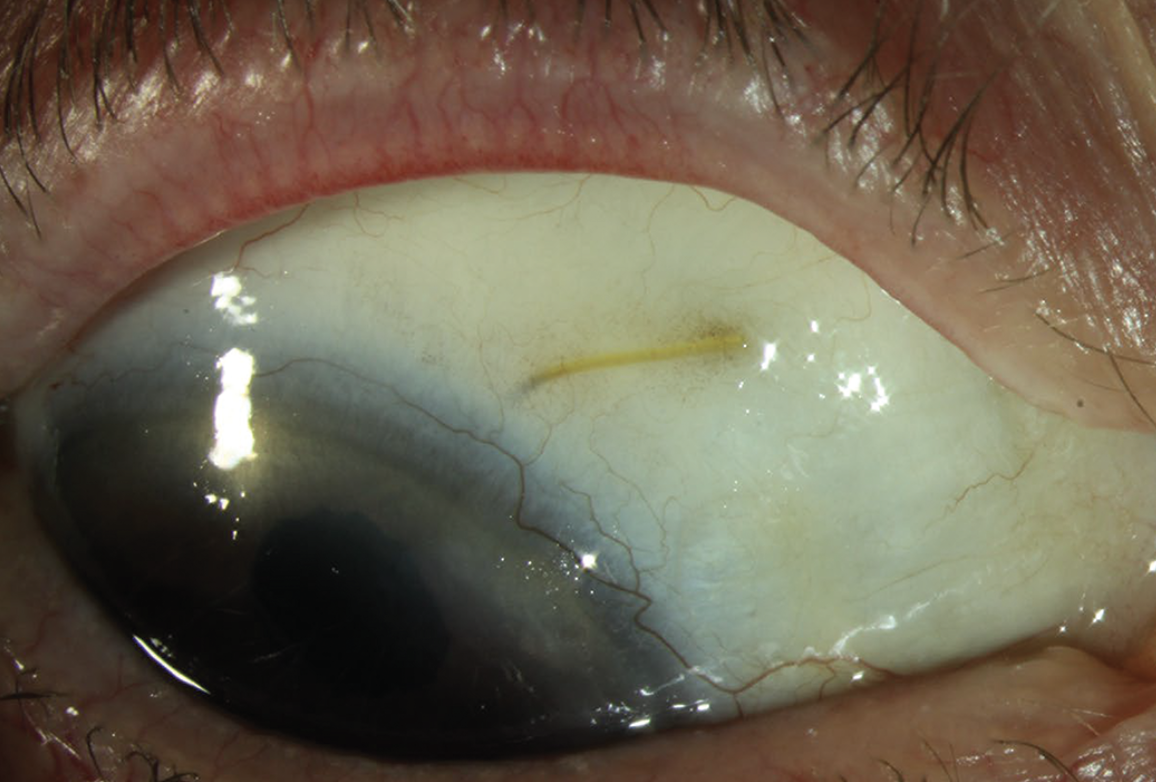

| Figure 1. External photograph, right eye. |

Examination

At presentation, visual acuity was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left. IOP was 21 and 16 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. External examination was unremarkable. Pupils were equal, round and reactive without afferent pupillary defect. Motility and confrontation visual fields were normal bilaterally. Ocular adnexae of both eyes were normal.

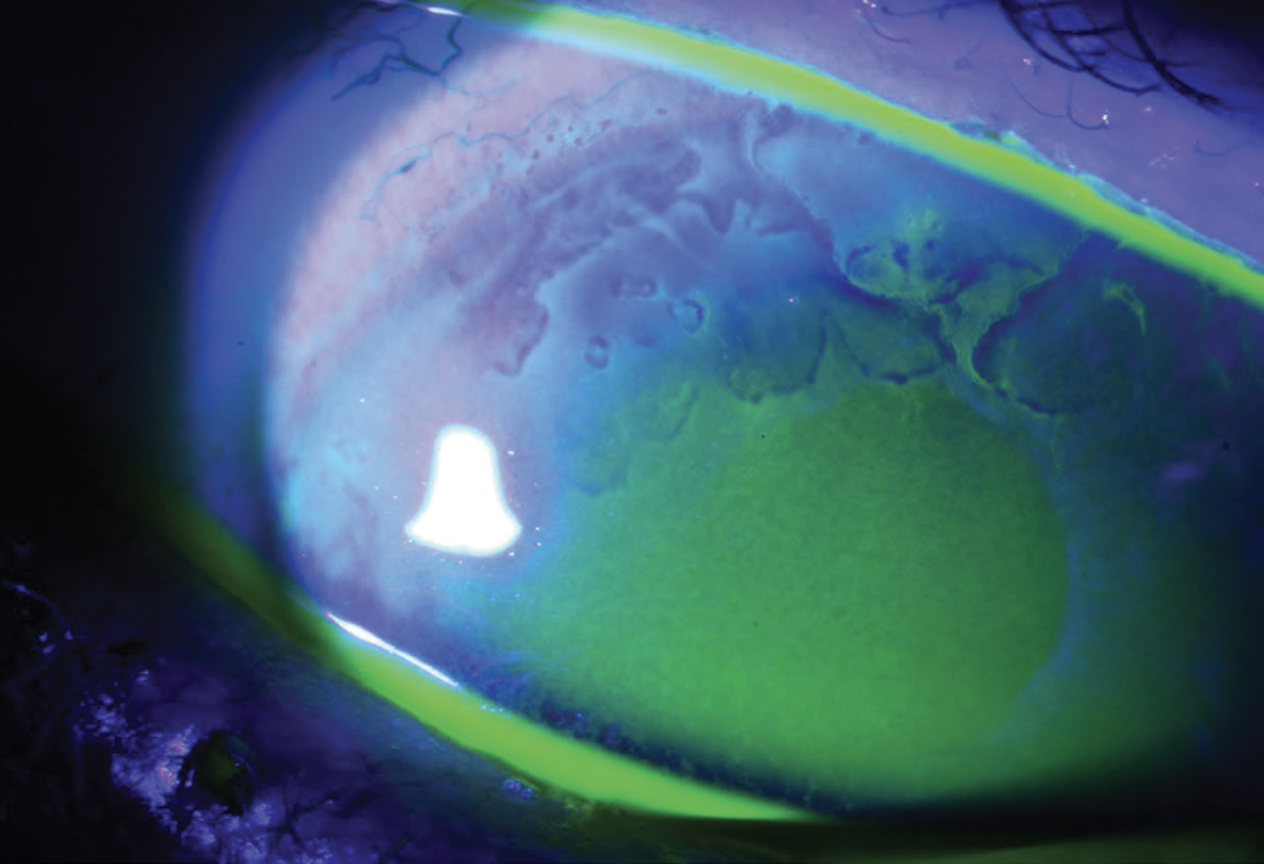

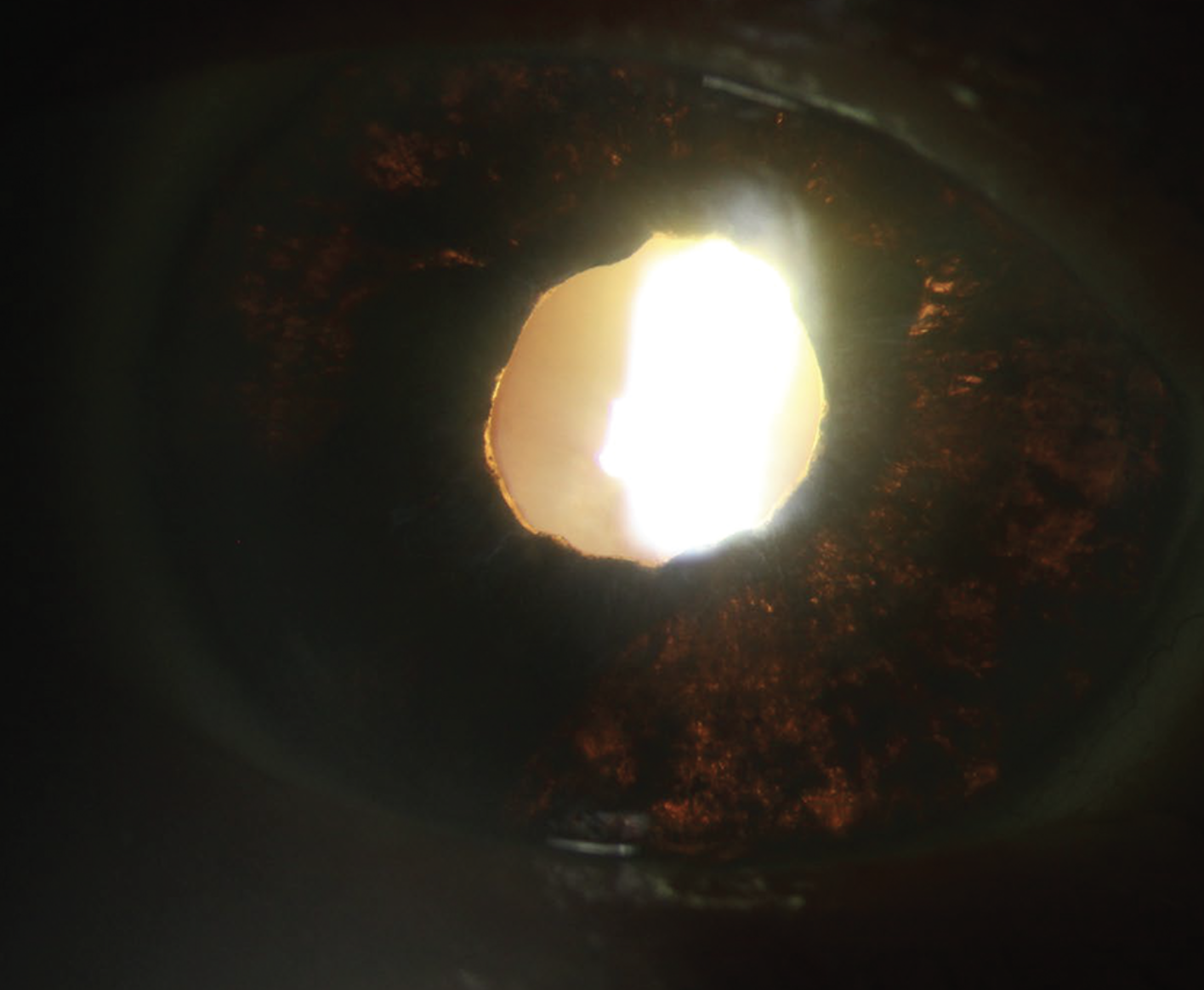

In the right eye, there was mild blepharitis and white conjunctiva without scleritis or ciliary flush. A Xen gel stent was well-covered superonasally with both vascularization and a flat bleb (Figure 1). There were no keratic precipitates, edema or infiltrates, although limbal stem-cell deficiency was present superiorly (Figure 2). The anterior chamber was deep with 1+ flare but no cells. The iris had scattered patchy mid-peripheral transillumination defects without nodules or neovascularization (Figure 3). A centered PC IOL was present. Posterior exam revealed advanced cupping with cup-to-disc ratio of greater than 0.9 with trace vitreous cell and posterior vitreous detachment.

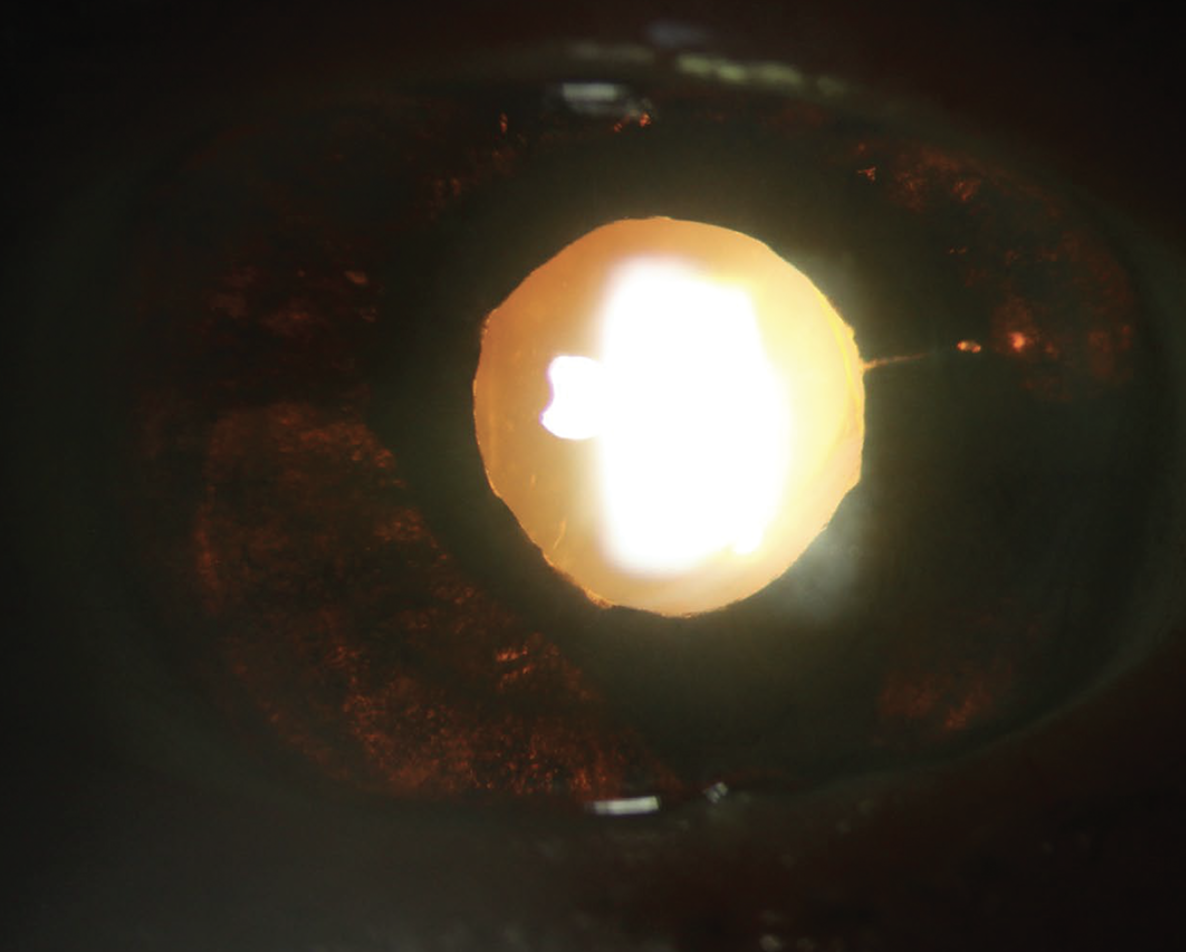

The left eye also had mild blepharitis and white conjunctiva without scleritis or ciliary flush. The cornea was without keratic precipitates, edema or infiltrates; the anterior chamber was deep and quiet. The iris had patchy mid-peripheral transillumination defects 360 degrees without nodules or neovascularization (Figure 4). A centered PC IOL was present. Posterior exam revealed a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3 with trace vitreous cell and posterior vitreous detachment.

What’s your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

|

| Figure 2. Fluorescein stain, right eye. |

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

Automated visual field testing, optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography were performed. Visual fields revealed dense, glaucomatous defects of the right eye. OCT of the retinal nerve fiber layer was consistent with glaucomatous damage since the macular OCT didn’t reveal explanatory retinal pathology. Fluorescein angiography showed normal arteriovenous transit time without macular or vascular leakage.

Given the clinical history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with sequelae of bilateral acute iris transillumination (BAIT) secondary to oral moxifloxacin use in 2010. It was presumed that BAIT, rather than pseudoexfoliation, was the etiology of her pigmentary glaucoma. She was counseled to avoid oral fluoroquinolones at all costs. There was no bleb over the Xen gel stent in her right eye; IOP was also above target of 10 to 12 mmHg. She was offered gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, Omni or a tube shunt in the right eye to better control her IOP, and she planned to discuss these options with her outside glaucoma specialist. She was told to continue the prednisolone acetate 1% once daily in the right eye as she self-reported severe pain on prior attempts of stopping the drop.

Ten months later, the patient returned for a follow-up visit at Wills Eye Hospital. In the interim, she had undergone GATT in the right eye, unfortunately complicated by visually significant vitreous hemorrhage. She was taken off the latanoprost OD. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/80 in the right and 20/70 in the left. IOP was 13 mmHg in both eyes. Exam was otherwise unchanged. The BAIT was deemed to be stable, and she was told to follow up with the Uveitis clinic in six months.

|

| Figure 3. Iris transillumination, right eye. |

Discussion

Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris (BADI) was first described in a 2004 case series in five patients who presented with sudden-onset ocular discomfort and were all found to have varying degrees of iris depigmentation; none of the eyes had “iris transillumination defects, inflammatory keratic precipitates or inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber.”1 In the years since, BAIT has joined BADI to form a spectrum of diseases with varying amounts of depigmentation and transillumination defects.2 Both conditions involve iris pigmentary release (from the epithelium in BAIT and the stroma in BADI) leading to the potential for trabecular meshwork occlusion and resultant pigmentary glaucoma.3

BADI and BAIT are rare, with fewer than 100 published cases (primarily in Europe and the Middle East) in the literature to date.4 The vast majority of patients present with acute ocular pain and photophobia, presumed to be related to the defects in the iris. In a 2019 literature review,4 60 of the 93 reported patients were women, with a mean age of 46 ±9 years. Notably, 69 percent of patients in this study had an upper respiratory tract infection in the days or weeks preceding the onset of their ocular symptoms; 81 percent of these patients had been treated with oral or intravenous antibiotic therapy, often with moxifloxacin.4 Other studies have also identified prior fluoroquinolone therapy as a potential trigger for BADI and BAIT.5-7 HLA-B51 and HLA-B27 have been implicated in 20 to 40 percent of patients, implying underlying autoimmune and genetic etiologies may sensitize certain patients to fluoroquinolone treatment.5,8 One report demonstrating simultaneous onset of BADI in two siblings highlights this possibility.9 Interestingly, COVID-19 has also been shown to be associated with development of BADI.10

Of note, only systemic (rather than topical) fluoroquinolones have been implicated in BADI and BATI; in a 2013 case report, glaucoma specialist Robert Knape postulated that this may be in part to pharmacokinetic variations between the two forms of administration.11 Topical moxifloxacin results in over tenfold higher concentrations in the aqueous humor than in the vitreous compared to oral administration, which yields comparable levels in both compartments.12,13 In addition, systemic moxifloxacin likely maintains high steady-state concentrations in the ocular tissues “at risk” compared to the intermittent levels allowed by topical therapy. As the exact pathogenesis of BADI and BAIT is poorly understood,14 the mechanism behind moxifloxacin-induced BADI/BAIT in particular (as compared to other fluoroquinolones) is largely unknown.5

Both syndromes exhibit increased intraocular pressure, but BAIT tends to have a higher and more frequent occurrence compared to BADI; this may be in part to the permanence of transillumination over simple depigmentation. In BAIT, high IOP occurs earlier and often leads to post-BAIT pigmentary glaucoma.2 Many patients require ongoing topical treatment and filtering surgeries to control IOP.15,16 Overall, BADI appears to be more reversible and has a better prognosis.

|

| Figure 4. Iris transillumination, left eye. |

Treatment of both BAIT and BADI involves mitigation of risk factors, management of symptoms and control of complications. Fluoroquinolones, if relevant to the patient’s history, must be discontinued. Topical corticosteroids have been used in larger case series17 but with equivocal response; attempts to taper topical corticosteroids, however, have been showed to trigger a recurrence in presenting symptoms.9 Cases with elevated IOP seem to be particularly refractive to topical therapies; in one study, anti-hypertensive medications demonstrated sufficient IOP control in only 53 percent of eyes.3 Laser iridoplasty, filtration surgeries with mitomycin C and trabeculotomy ab interno are procedures that have been pursued in eyes requiring better IOP control.16,18,19 Given the low global prevalence of BAIT and BADI, the true disease course of both syndromes is difficult to characterize. Some cases appear to resolve completely within 14 months18 with BADI irises showing potential for full re-pigmentation;17 other patients with BAIT endure persistent symptoms and complications from iris transillumination and glaucomatous damage.

Ultimately, BADI and BAIT are rare disease entities presenting with photophobia and decreased vision, often instigated by oral or intravenous fluroquinolone therapy following an upper respiratory infection. Both syndromes (BAIT in particular) can lead to elevated IOP that may masquerade as simple pigmentary glaucoma; in these patients, IOP control is difficult and may require repeated surgical treatment. In our case, this 81-year-old female was diagnosed with BAIT over 10 years after fluoroquinolone exposure with severe vision loss in one eye from BAIT-induced glaucoma.

1. Tugal-Tutkun I, Urgancioglu M. Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2006;244:6:742-6.

2. Tugal-Tutkun I, Onal S, Garip A, et al. Bilateral acute iris transillumination. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:10:1312-9.

3. Tranos P, Lokovitis E, Masselos S, Kozeis N, Triantafylla M, Markomichelakis N. Bilateral acute iris transillumination following systemic administration of antibiotics. Eye (Lond) 2018;32:7:1190-1196.

4. Perone JM, Chaussard D, Hayek G. Bilateral acute iris transillumination (BAIT) syndrome: Literature review. Clin Ophthalmol 2019;13:935-943.

5. Hinkle DM, Dacey MS, Mandelcorn E, et al. Bilateral uveitis associated with fluoroquinolone therapy. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2012;31:2:111-6.

6. Kreps EO, Hondeghem K, Augustinus A, et al. Is oral moxifloxacin associated with bilateral acute iris transillumination? Acta Ophthalmol 2018;96:4:e547-e548.

7. Morshedi RG, Bettis DI, Moshirfar M, Vitale AT. Bilateral acute iris transillumination following systemic moxifloxacin for respiratory illness: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2012;20:4:266-72.

8. Wefers Bettink-Remeijer M, Brouwers K, van Langenhove L, et al. Uveitis-like syndrome and iris transillumination after the use of oral moxifloxacin. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:12:2260-2.

9. Amin R, Nabih A, Khater N. Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris in two siblings simultaneously. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2018;10:257-260.

10. Soydan A, Kaymaz A. Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris determined in two cases after COVID-19 infection. Indian J Ophthalmol 2023;71:3:1030-1032.

11. Knape RM, Sayyad FE, Davis JL. Moxifloxacin and bilateral acute iris transillumination. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 2013;3:1:10.

12. Hariprasad SM, Blinder KJ, Shah GK, et al. Penetration pharmacokinetics of topically administered 0.5% moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution in human aqueous and vitreous. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1:39-44.

13. Hariprasad SM, Shah GK, Mieler WF, et al. Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered moxifloxacin in humans. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:2:178-82.

14. Tugal-Tutkun I, Altan C. Bilateral Acute Depigmentation of Iris (BADI) and Bilateral Acute Iris Transillumination (BAIT)-An update. Turk J Ophthalmol 2022;52:5:342-347.

15. Hernandez Pardines F, Serra Verdu MC, Font Julia E, Molina Martin JC. Aqueous humor misdirection syndrome after glaucoma filtering surgery in patient with bilateral acute iris transillumination (BAIT) syndrome. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 2018;93:9:444-446.

16. Den Beste KA, Okeke C. Trabeculotomy ab interno with Trabectome as surgical management for systemic fluoroquinolone-induced pigmentary glaucoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:43:e7936.

17. Tugal-Tutkun I, Araz B, Taskapili M, et al. Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris: Report of 26 new cases and four-year follow-up of two patients. Ophthalmology 2009;116:8:1552-7, 1557 e1.

18. Willermain F, Deflorenne C, Bouffioux C, Janssens X, Koch P, Caspers L. Uveitis-like syndrome and iris transillumination after the use of oral moxifloxacin. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:8:1419; author reply 1419-20.

19. Gonul S, Bozkurt B. Bilateral acute iris transillumination (BAIT) initially misdiagnosed as acute iridocyclitis. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2015;78:2:115-7.