Presentation

A 76-year-old white man presented to his ophthalmologist with sudden decreased vision in the right eye, which occurred two months prior and had not improved.

Medical History

The patient had a central retinal vein occlusion in the left eye in 2020. He denied other past ocular history. Past medical history included coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and actinic keratosis. Family history was non-contributory. The patient had a history of tobacco smoking and drank alcohol socially. Current medications included atorvastatin 40 mg daily and aspirin 81 mg daily.

Exam

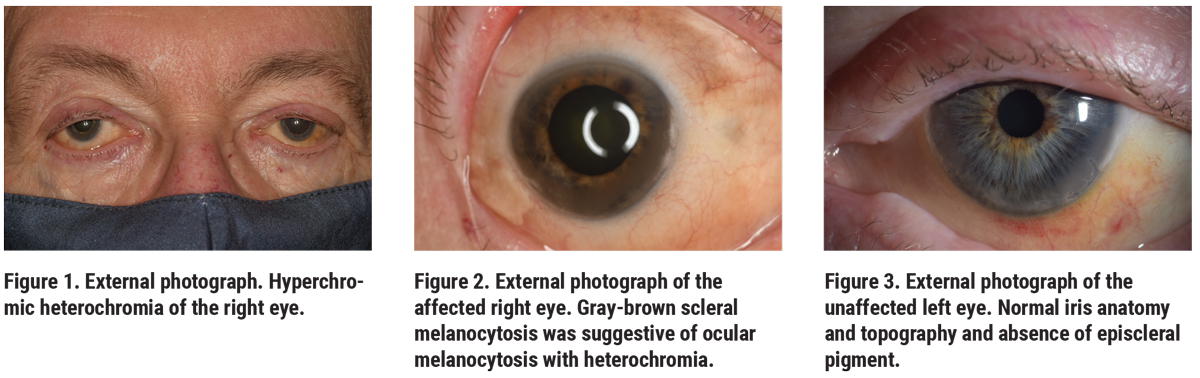

On examination, visual acuity was hand motions OD and 20/60 OS, with intraocular pressures of 20 mmHg OD and 14 mmHg OS. There was no afferent pupillary defect. The external examination was notable for prominent scleral and iris melanocytosis OD, and moderate nuclear sclerotic cataract in each eye (Figures 1-3). View of the right fundus was obscured by vitreous hemorrhage. The left fundus examination was notable for chronic vascular changes consistent with an old central retinal vein occlusion.

|

What is your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

|

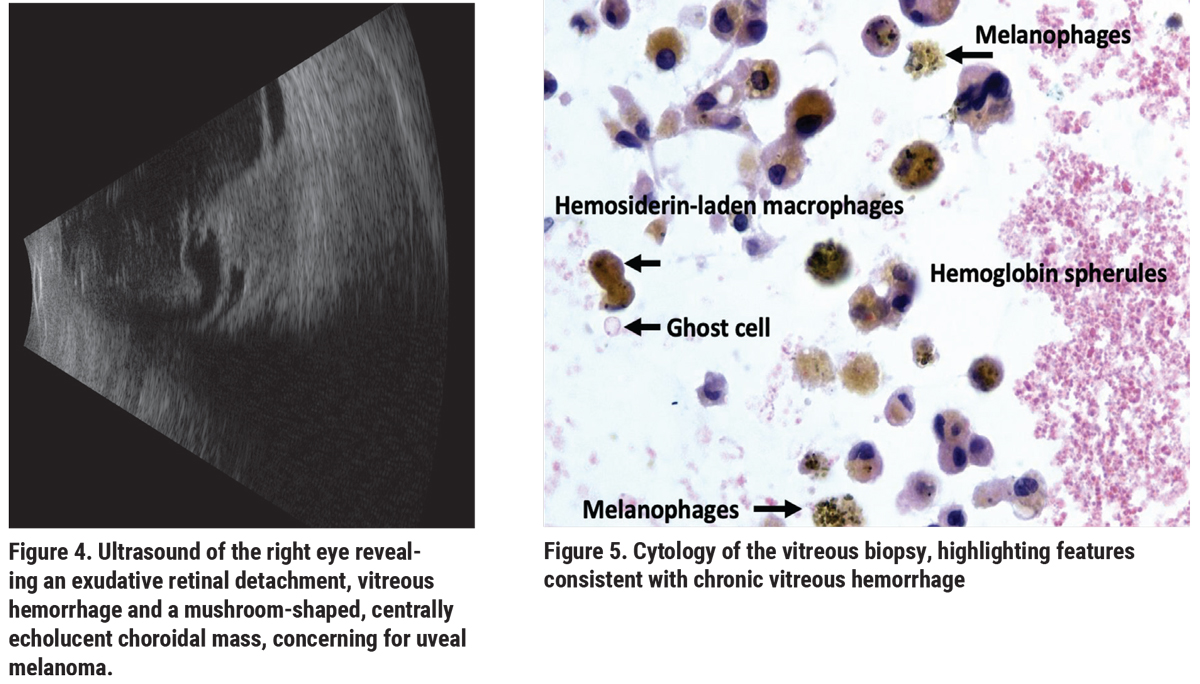

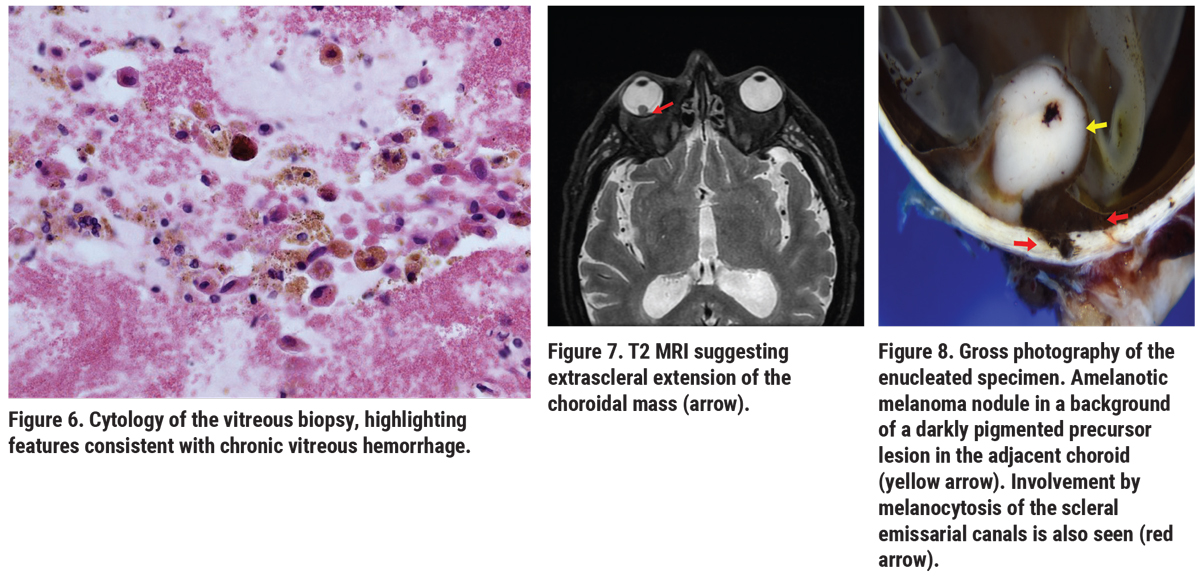

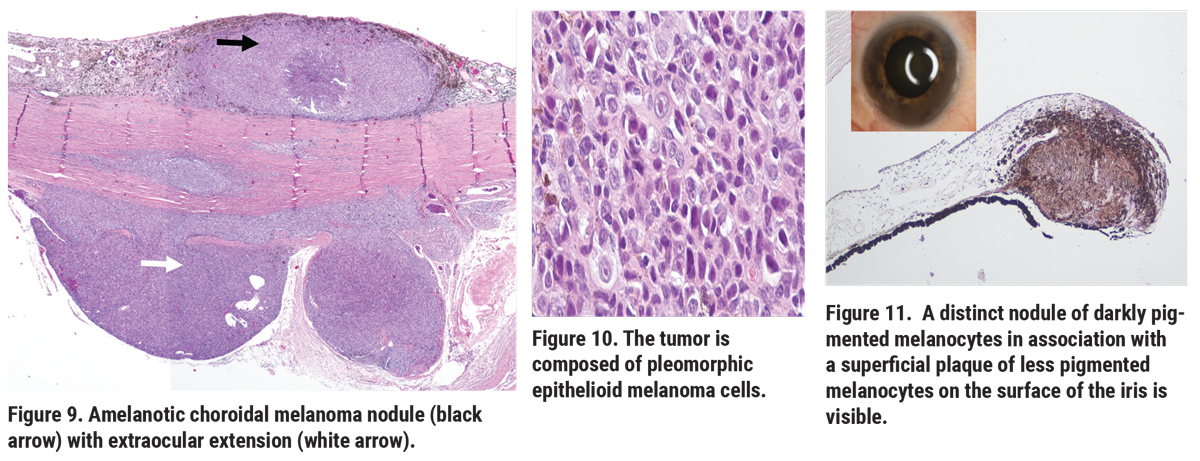

Ultrasonography OS revealed vitreous debris, suggestive of blood, and serous retinal detachment overlying an intraocular mushroom-shaped mass measuring approximately 11 mm in the largest basal diameter and 8 mm in thickness (Figure 4). These findings were suggestive of uveal melanoma. A vitrectomy was performed to clear the view for intraocular tumor assessment and possible plaque placement. Vitreous cytology revealed chronic vitreous hemorrhage that contained malignant cells (Figures 5, 6). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) disclosed an intraocular mass with extrascleral extension (Figure 7) and enucleation was recommended. Histopathology of the enucleated eye showed choroidal melanoma with extraocular extension arising in ocular melanocytosis. Additionally, a second melanocytic nodule was noted in the iris, interpreted as an atypical iris tumor (Figures 8-11).

|

Discussion

Congenital ocular melanocytosis is defined as a congenital nevus composed of dendritic melanocytes involving ocular tissues, including the sclera, episclera and uvea.1 The condition is called oculodermal melanocytosis or the Nevus of Ota if the tissues of the periocular skin and orbit are involved. Congenital ocular melanocytosis affects less than 1 percent of the Caucasian population and is bilateral in 10 percent of cases.1 It’s been hypothesized that ocular melanocytosis is caused by the arrest or abnormal migration of neural crest-derived melanocytes to the eyelid, orbit and uvea, rather than to the dermoepidermal junction.3 Histopathologically, ocular melanocytosis is characterized by the proliferation of intensely pigmented dendritic melanocytes in the affected tissue.1,3 GNAQ and GNA11 mutations have been identified in ocular melanocytosis, conventional uveal tract nevi, uveal melanocytoma and uveal melanoma, indicating that GNAQ and GNA11 mutations are likely an initiating event in the pathogenesis of these melanocytic conditions.

|

The lifetime risk in Caucasians for the development of uveal melanoma in a setting of ocular melanocytosis is approximately 1 in 400.1,2 A large study of 7,872 patients with uveal melanoma revealed associated oculodermal melanocytosis in 3 percent of them.4 Oculodermal melanocytosis not only increases the risk for uveal melanoma, but it also increases the relative risk of metastasis (1.6 times as compared to those with no melanocytosis).4 This relative risk was greatest among patients with melanocytosis involving the iris (RR 2.8), choroid (RR 2.6) and sclera (RR 1.9).4 Metastases of uveal melanoma arising in ocular melanocytosis carry a less favorable prognosis than metastasis from uveal melanoma without associated ocular melanocytosis.4,5 Thus, screening ophthalmologic examinations of patients with ocular melanocytosis at risk for uveal melanoma are recommended every six months.

In summary, vitreous hemorrhage was the presenting manifestation of uveal melanoma in this patient. The incidence of vitreous hemorrhage is seven cases per 100,000.6 There’s a broad differential for vitreous hemorrhage. Common causes include hemorrhagic posterior vitreous or retinal detachment, diabetic eye disease, trauma and vascular occlusive disease. Although less frequent, vitreous hemorrhage can be associated with posterior uveal melanoma, but is relatively uncommon.7

Generally, vitreous hemorrhage occurs in a subset of melanomas that have broken through Bruch’s membrane and perforated the overlying retina. Retinal perforation is more likely to occur when choroidal tumors originate where the retina and choroid normally are adherent, such as at the ora serrata or the peripapillary choroid. This case highlights the importance of periodic monitoring of patients with ocular melanocytosis for development of uveal melanoma and emphasizes that intraocular tumor should be included in the differential diagnosis of vitreous hemorrhage. Intraocular tumor must be considered in all cases of vitreous hemorrhage, and excluded with a careful history, examination and ultrasonography.

1. Shields JA, Shields CL. Eyelid, Conjunctival, and Orbital Tumors: An Atlas and Textbook. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008.

2. Singh AD, De Potter P, Fijal B, et al. Lifetime prevalence of uveal melanoma in white patients with oculo(dermal) melanocytosis. Ophthalmology 1998;107:195-98.

3. Shaffer D, Walker K, Weiss GR. Malignant melanoma in a Hispanic male with nevus of Ota. Dermatology 1992;185:2:146-50.

4. Shields CL, Kaliki S, Livesey M, et al. Association of ocular and oculodermal melanocytosis with the rate of uveal melanoma metastasis: Analysis of 7,872 consecutive eyes. JAMA Ophthalmology 2013;131:993-1003.

5. Mashayekhi A, Kaliki S, Walker B, Park C, Sinha N, Kremer FZ, Shields CL, Shields JA. Metastasis from uveal melanoma associated with congenital ocular melanocytosis: a matched study. Ophthalmology 2013;120:7:1465-8.

6. Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Vitreous Hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol 1997;42:1:3-39.

7. Lindgren G, Lindblom B. Causes of vitreous hemorrhage. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1996;7:3:13-9.