Floppy eyelid syndrome was first described by William Culbertson, MD, and H. Bruce Ostler, MD, in 1981. They described a series of 11 overweight men with chronic irritative symptoms and rubbery, easily-everted upper eyelids and papillary conjunctivitis. Since the initial description, similar findings have been observed in female, non-obese and pediatric populations, leading many authors to suggest the term lax eyelid syndrome to encompass this broader spectrum of affected patients. Nomenclature aside, LES presents a diagnostic and treatment challenge to the ophthalmologist and oculoplastic surgeon alike.

|

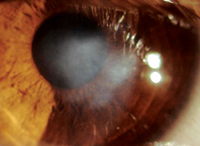

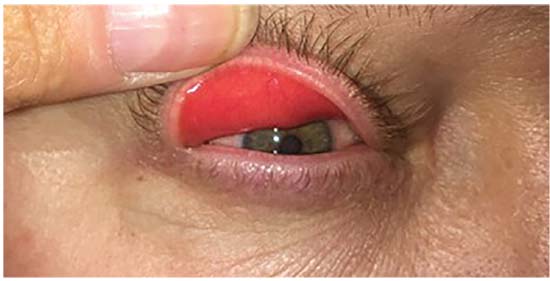

| Figure 1: Eversion of an upper eyelid with gentle digital pressure. Note the injected palpebral conjunctiva. Slit lamp examination shows papillary conjunctivitis. |

Pathogenesis

The abnormality in LES is localized to the tarsus, which is a connective tissue plate that’s larger and more defined in the upper eyelid, 8 to 10 mm tall centrally. In patients with LES, the tarsus becomes malleable and is easily everted with mild external force. Why this happens is not completely understood. Drs. Culbertson and Ostler noted unilateral disease in patients who favored one side during sleep and bilateral disease in patients sleeping face down, implicating nocturnal eversion.1 This mechanical theory, however, doesn’t fully explain any associated corneal or epibulbar irritation. Many studies demonstrate concomitant tear-film abnormalities including Demodex mites, meibomian gland atrophy and blepharitis that may exacerbate reduced globe-eyelid apposition, leading to a symptomatic patient. At the histologic level, early studies showed nonspecific inflammation of the tarsus,1 while more recent studies reveal reduced elastic fibers and upregulation of elastin-degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases, particularly MMP-7 and MMP-9.

LES is linked to a variety of ocular and systemic conditions including obesity, keratoconus, eyelash ptosis and, most notably, obstructive sleep apnea.3 OSA is a common and likely underdiagnosed entity characterized by nocturnal airway collapse for more than 10 seconds. This chronic hypoventilation leads to hypertension, heart disease and motor vehicle accidents, and has also been implicated in ischemic ocular disease including low-tension glaucoma and ischemic optic neuropathy. Because LES and OSA often occur concurrently, the ophthalmologist may be the first to identify a systemic condition associated with high morbidity.

Diagnosis

Although classic FES describes a subgroup of obese, male patients, the expanded definition of LES encompasses a variety of patients with eyelid laxity and associated corneal, conjunctival or tear-film pathology.9 Thus, this diagnosis should be considered even in patients who don’t meet the classic demographic. Patients present with symptoms of pain, swelling, irritation, foreign-body sensation, tearing and ocular discharge. The most common ocular sign is a papillary conjunctivitis, occurring in up to 98 percent of LES patients. Other ocular findings include keratopathy, filamentary keratitis, infectious keratitis, recurrent corneal erosion, tear insufficiency and eyelash ptosis.8

The hallmark of the condition is eyelid laxity. This can be evaluated subjectively by easy or spontaneous eyelid eversion with gentle digital pressure (Figure 1). It can also be assessed with the “snap-back” test: distraction of the eyelid >8 mm away from the globe, or done more formally with a “laxometer” device.9,10 When eyelid laxity exists in the presence of anterior segment findings, especially papillary conjunctivitis, the diagnosis can be assumed.

Because of the high morbidity and mortality of OSA, patients should be asked about snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness and obesity. Ophthalmologists should maintain suspicion for OSA and refer patients to their primary care physician or pulmonologist. OSA can be diagnosed with polysomnography and treated with weight loss, continuous positive airway pressure and, occasionally, with pharyngeal surgery. Following is a discussion of treatment approaches.

Non-surgical Measures

The diagnosis of LES can be challenging, and often these patients have been chronically treated with a variety of topical medications. Multiple topical medications should be stopped to eliminate confounding medicamentosa. They can then be added back one at a time. Topical measures consist of artificial tear drops, gels and ointments, and topical steroids. The eye can be shielded or taped shut at night. Moisture chambers, eyelid scrubs or punctal plugs may also be used.1,12

|

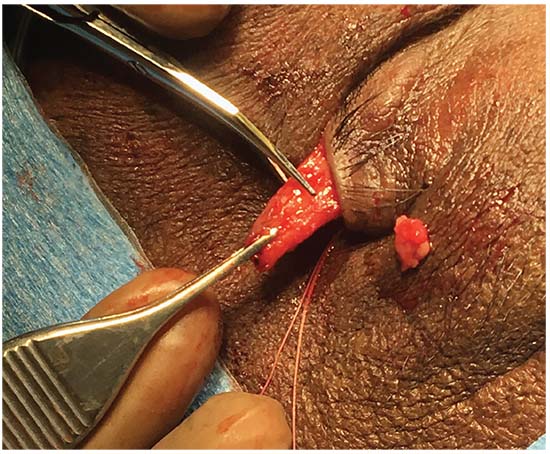

| Figure 2: Intraoperative photograph of a patient undergoing an upper eyelid lateral tarsal strip procedure. The tarsal strip has been developed and the eyelid is placed on lateral stretch to determine the amount of the strip to be excised to restore anatomic tone to the eyelid. The strip will then be fixated to the periosteum of the orbital rim in the region of Whitnall’s tubercle. |

Surgical Options

When conservative measures fail, surgery is indicated. The goal of surgery is to reduce horizontal eyelid laxity, improve globe apposition and limit spontaneous eyelid eversion, thereby eliminating nocturnal exposure. Various surgical techniques have been described, including full-thickness wedge excision (FTWE), lateral tarsal strip (LTS), lateral canthal plication, and lateral tarsorrhaphy. FTWE and LTS will be discussed here.

• Full-thickness wedge excision. The FTWE procedure is usually performed by excising a pentagon-shaped wedge of full-thickness eyelid at the lateral one-third of the lid. The wound edges are then approximated in a manner similar to repair of a full-thickness eyelid defect: Sequential suturing of the gray line, lash line, tarsal plate, preseptal orbicularis and skin. The amount of tissue resected varies based on the severity of the disease and can be determined perioperatively by laterally stretching the eyelid to a more appropriate upper-lid tension. It’s not unusual to excise up to 20 mm of tarsus in these patients. Caution must be taken to avoid injury to the ductules of the lacrimal gland which are located 5 mm superior to the lateral-most edge of tarsus in the upper eyelid. There are various modifications to the skin closure that can reduce cutaneous redundancy, including the classic Burow’s triangle and myocutaneous flaps.

• Lateral tarsal strip. While LTS is a commonly performed procedure in the lower eyelid, it can also be used to address upper eyelid horizontal laxity and offers the benefit of preserving the tarsus.13 Upper eyelid LTS is performed through cantholysis of the superior limb of the lateral canthal tendon followed by identification of the orbital rim. A strip can be fashioned in a technique similar to lower eyelid LTS: division of the anterior and posterior lamellae and resection of the mucocutaneous junction. The lateral canthal tendon is resected; a varying amount of the lateral tarsus is also resected depending on the severity of the disease. The strip is then fixated to the periosteum of the lateral orbital rim in the region of Whitnall’s tubercle using a 4-0 or 5-0 permanent suture placed in a horizontal mattress fashion. The lateral canthus is then reformed and the anterior lamellar incision closed. This incision can be fashioned such that the surgical scar is hidden in the natural eyelid crease. The beneficial effect of LTS is in tarsal shortening, but also likely in the creation of a broader pivot point at the lateral orbital rim, thereby reducing spontaneous eversion.13

Conclusion

The spectrum of LES should be considered for patients with nonspecific complaints and anterior segment findings who demonstrate upper and lower eyelid laxity. The most common ocular finding is papillary conjunctivitis. OSA should be suspected in these patients and can be diagnosed in conjunction with the primary care physician or pulmonologist. In this way, the ophthalmologist can play a pivotal role in diagnosis of this major public health concern. REVIEW

Dr. Armstrong is a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, and a member of the Wills Eye Hospital Orbital and Oculoplastic Surgery Service. She practices at Armstrong, George, Cohen, Will Ophthalmology in Hatboro, Pennsylvania.

1. Culbertson W, Ostler H. The floppy eyelid syndrome. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1981;92:4:568–75.

2. Eiferman R, Gossman MD, O’Neill K, et al. Floppy eyelid syndrome in a child. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 1991;7:1:74.

3. Woog J. Obstructive sleep apnea and the floppy eyelid syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;15;110:3:314-5.

4. Burkat C, Lemke BN. Acquired lax eyelid syndrome. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2005;21:1:52–58.

5. Tanenbaum M. A rational approach to the patient with floppy/lax eyelids. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:9:663-4.

6. Van den Bosch WA, Lemij HG. The lax eyelid syndrome. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1994;78:9:666–70.

7. Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Stojkovic M, Hofmann-Rummelt C, et al. The pathogenesis of floppy eyelid syndrome involvement of matrix metalloproteinases in elastic fiber degradation. Ophthalmology 2005;112:4:694–704.

8. Pham TT, Perry JD. Floppy eyelid syndrome. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2007;18:5:430-3.

9. Fowler A, Dutton JJ. Floppy eyelid syndrome as a subset of lax eyelid conditions: Relationships and clinical relevance (an ASOPRS thesis). Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2010;26:3:195–204.

10. Sward M. Lax eyelid syndrome (LES), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and ocular surface inflammation. The Ocular Surface 2018;16:3:331–36.

11. Karger RA, White WA, Park WC, et al. Prevalence of floppy eyelid syndrome in obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome. Ophthalmology 2006;113:9:1669–74.

12. Moore MB, Harrington J, McCulley JP. Floppy eyelid syndrome: Management including surgery. Ophthalmology 1986;93:2:184-8

13. Ezra DG, Beaconsfield M, Sira M, et al. Long-term outcomes of surgical approaches to the treatment of floppy eyelid syndrome. Ophthalmology 2010;117:4:839–46.

14. Vrcek I, Chou E, Blaydon S, et al. Wingtip flap for reconstruction of full-thickness upper and lower eyelid defects. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2017;33:2:144–146.