Workup, Diagnosis and Treatment

|

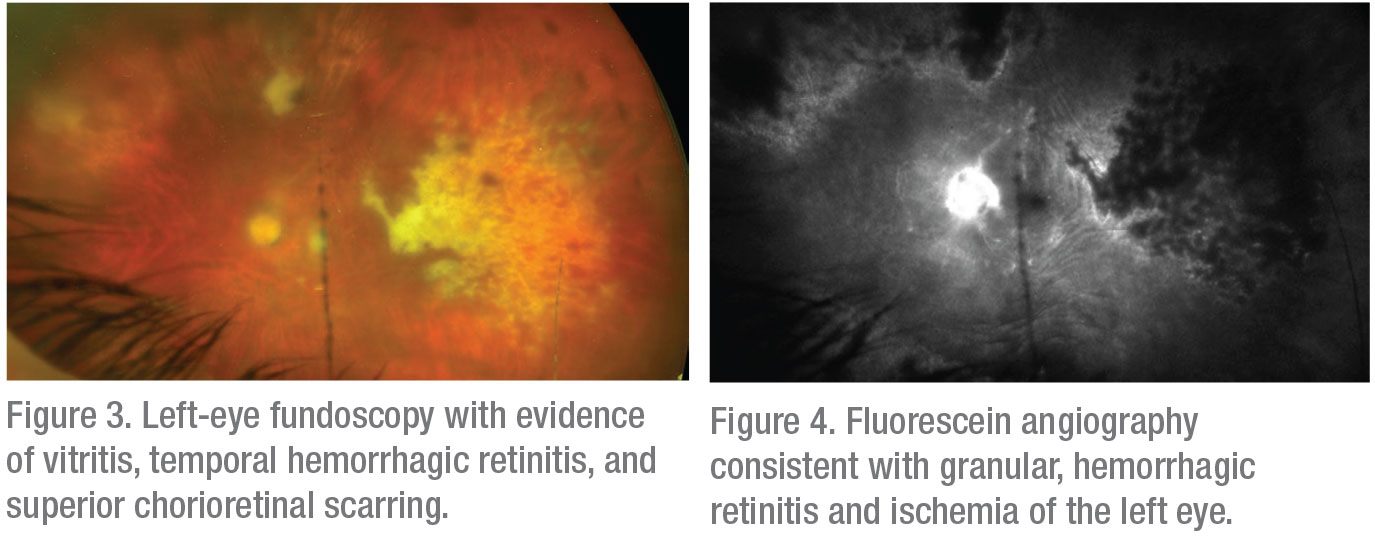

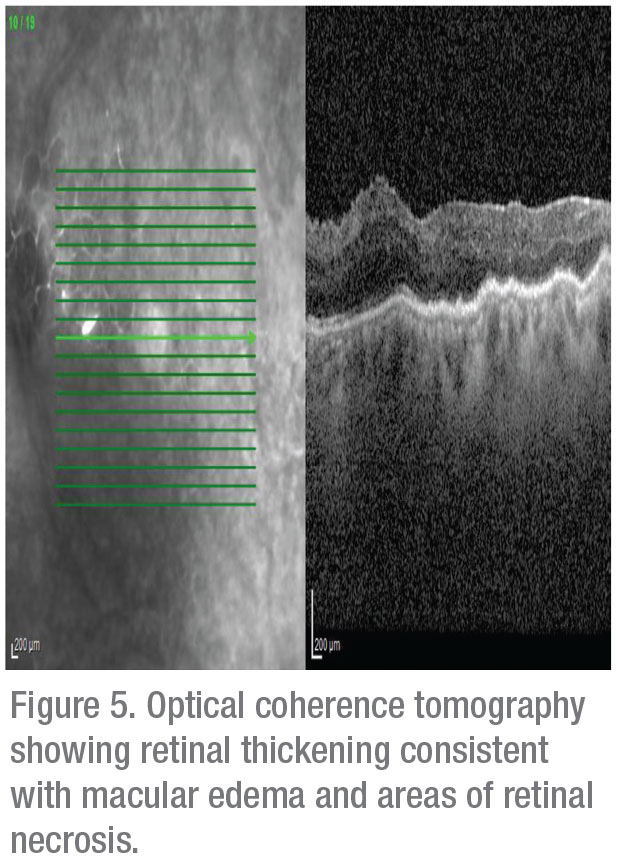

The differential for this patient’s decreased vision and associated retinal findings was broad. The retina of the left eye appeared to have lesions that suggested retinal necrosis, and thus suspicion for an infectious etiology was high. Possible diseases included acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, cytomegalovirus retinitis, toxoplasmic retinitis and bacterial or fungal retinitis. Possible inflammatory causes included Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, Behçet’s disease and sarcoidosis.

An anterior chamber paracentesis was performed on the left eye with an aqueous sample sent for herpesviral and Toxoplasma gondii polymerase chain reaction testing. The aqueous tested positive for CMV at a titer of 1,100,000

IU/mL.

Treatment was promptly initiated for CMV retinitis in the setting of local immunocompromise. At Wills Eye Hospital he was treated with valganciclovir 900 mg twice a day for three weeks, then 900 mg once daily thereafter.

At six week follow-up the patient had mild improvement of his retinitis on fundoscopy. He was continued on a regimen of valganciclovir 900 mg daily and difluprednate 0.05% twice a day with plans for follow-up in two months.

Discussion

|

In an immunocompromised host, CMV, which circulates through the bloodstream following primary infection, may spread to the retina through the retinal vasculature. Individuals with HIV are known to have damaged vascular endothelium and decreased blood flow through the retina that predisposes them to develop subsequent retinitis.1 Also, though it’s rare, viral retinitis is a well-described complication of intraocular or periocular corticosteroid administration in patients without AIDS or iatrogenic immunosuppression.2-4 In immunocompetent patients, the theorized mechanism of infection is less well-described, but is likely due to localized retinal immunosuppression following local steroid administration that enables opportunistic infections such as CMV.2

Our patient had undergone a prolonged treatment course for CME that included two sub-Tenon’s steroid injections and 11 intravitreal steroid injections. The dose of steroids needed to cause local immunocompromise predisposing to viral retinitis varies significantly. Pleasanton, California, ophthalmologist Ako Takakura and her colleagues analyzed 30 reported cases of viral retinitis following intraocular or periocular corticosteroid administration and found that patients received doses ranging from 1.5 mg to 40 mg of differing forms of steroids prior to development of viral retinitis. The review also found that 85.7 percent of patients who developed viral retinitis had received only a single intravitreal steroid injection.3

Several studies have aimed to identify risk factors that place immunocompetent patients receiving intraocular steroid treatments at higher risk of developing viral retinitis. Several case reports have documented patients with known HIV with relative immune reconstitution and elevated CD4 counts on highly active anti-retroviral therapy who developed CMV retinitis following administration of intraocular steroid injections. This suggests that this subset of patients may be at higher risk of developing viral retinitis despite CD4 counts well above the usual level associated with CMV retinitis.3,4

Dr. Takakura reviewed 30 cases with viral retinitis following regional steroid injections or implants, of which 23 (76.7 percent) were due to CMV. Diabetes was the most common risk factor. Two patients developed recurrence of CMV retinitis following treatment for immune recovery uveitis.3 One study reported an incidence of CMV retinitis following intravitreal steroid injections of 3/334 (0.9 percent) in patients with an immune-altering condition, including one patient each with diabetes, HIV infection with prior CMV retinitis but CD4+ count >200 cells/mL, and chemotherapy. More frequent and higher doses of intravitreal steroids were also felt to be risk factors. The authors theorized that the persistent microangiopathy present in patients with diabetes mellitus both predisposed them to macular edema requiring steroid injection and facilitated entry of viruses such as CMV into the retina.4

While the foundation of management of CMV retinitis in the immunocompromised population involves immune reconstitution in combination with antiviral agents, no clear guidelines exist for treatment in the immunocompetent population. One study suggests that systemic therapy alone may be used for peripheral, non-sight-threatening lesions. The addition of intravitreal ganciclovir or foscarnet is recommended for patients with progression of disease despite systemic therapy or lesions near the macula or optic nerve.5 Systemic agents typically include oral ganciclovir or intraveneous ganciclovir, foscarnet or cidofovir.

The patient described in this case suffered from a course of chronic, anterior uveitis of the right eye that was thought to be due to recurrent graft rejection. A study of ocular manifestations of CMV in immunocompetent patients described precipitates that are often small, non-granulomatous and stellate in shape, as well as the “circinate” precipitates that are characteristic of CMV. Affected patients also often notably have keratic precipitates superior to the corneal equator.6,7 While our patient did have keratic precipitates localized to his DSAEK that could indeed represent recurrent graft rejection, it’s possible that they represented the first manifestation of chronic infection.

In summary, viral retinitis is a rare but well-reported complication of intraocular or periocular corticosteroid use of which ophthalmologists should remain aware. Cases have been reported following even a single dose of intravitreal triamcinolone. Patients with a history of HIV are at increased risk of developing recurrent CMV retinitis despite immune reconstitution, as are previously uninfected diabetic patients, due to predisposing vasculopathy. Treatment regimens vary greatly but typically involve a combination of systemic and intravitreal antiviral medications. CMV is an inflammatory condition with various insidious and devastating anterior and posterior intraocular presentations, even in the immunocompetent population. REVIEW

1. Faber DW, Wiley CA, Lynn GB, Gross JG, Freeman WR. Role of HIV and CMV in the

pathogenesis of retinitis and retinal vasculopathy in AIDS patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992;33:8:2345-53.

2. Vertes D, Snyers B, De potter P. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after low-dose intravitreous triamcinolone acetonide in an immunocompetent patient: A warning for the widespread use of intravitreous corticosteroids. Int Ophthalmol 2010;30:5:595-7.

3. Takakura A, Tessler HH, Goldstein DA, et al. Viral retinitis following intraocular or periocular corticosteroid administration: A case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2014;22:3:175-82.

4. Shah AM, Oster SF, Freeman WR. Viral retinitis after intravitreal triamcinolone injection in patients with predisposing medical comorbidities. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;149:3:433-40.e1.

5. Port AD, Orlin A, Kiss S, Patel S, D’amico DJ, Gupta MP. Cytomegalovirus retinitis: A review. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2017;33:4:224-234.

6. Joye A, Gonzales JA. Ocular manifestations of cytomegalovirus in immunocompetent hosts. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018;29:6:535-542.

7. Chan NS, Chee SP, Caspers L, Bodaghi B. Clinical features of CMV-associated anterior uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2018;26:1:107-115.