Every cataract surgeon will be faced with a patient in need of an IOL exchange for a range of reasons, including pathology, IOL dislocation or patients’ dissatisfaction with their visual outcome. Generally, when the exchange is warranted purely for optical reasons, it’s approached without a second thought, unless the posterior capsule has been opened previously. In this situation, it’s been a long-held belief that IOL exchange brings considerable risks.

The surgeons at Advanced Vision Care in Los Angeles say they’ve been under the impression that patients who needed an exchange fared just as well whether or not they had an open capsule, and whether or not the lens needed to be fixated in another fashion. It wasn’t until recently that they had the time to mine the data to evaluate this notion. They presented the results at October’s American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting in Chicago.

The paper, “Clinical Outcomes and Complications Following IOL Exchange in the Setting of an Open or Intact Posterior Capsule,” was presented by the lead author, Hasan Alsetri, BS. The paper was co-authored by Samuel Masket, MD, of Advanced Vision Care, and clinical professor at the Stein Eye Institute, UCLA; Nicole Fram, MD, of Advanced Vision Care; and Hector Sandoval, MD, of SUNY Downstate Medical School in Brooklyn, New York.

|

|

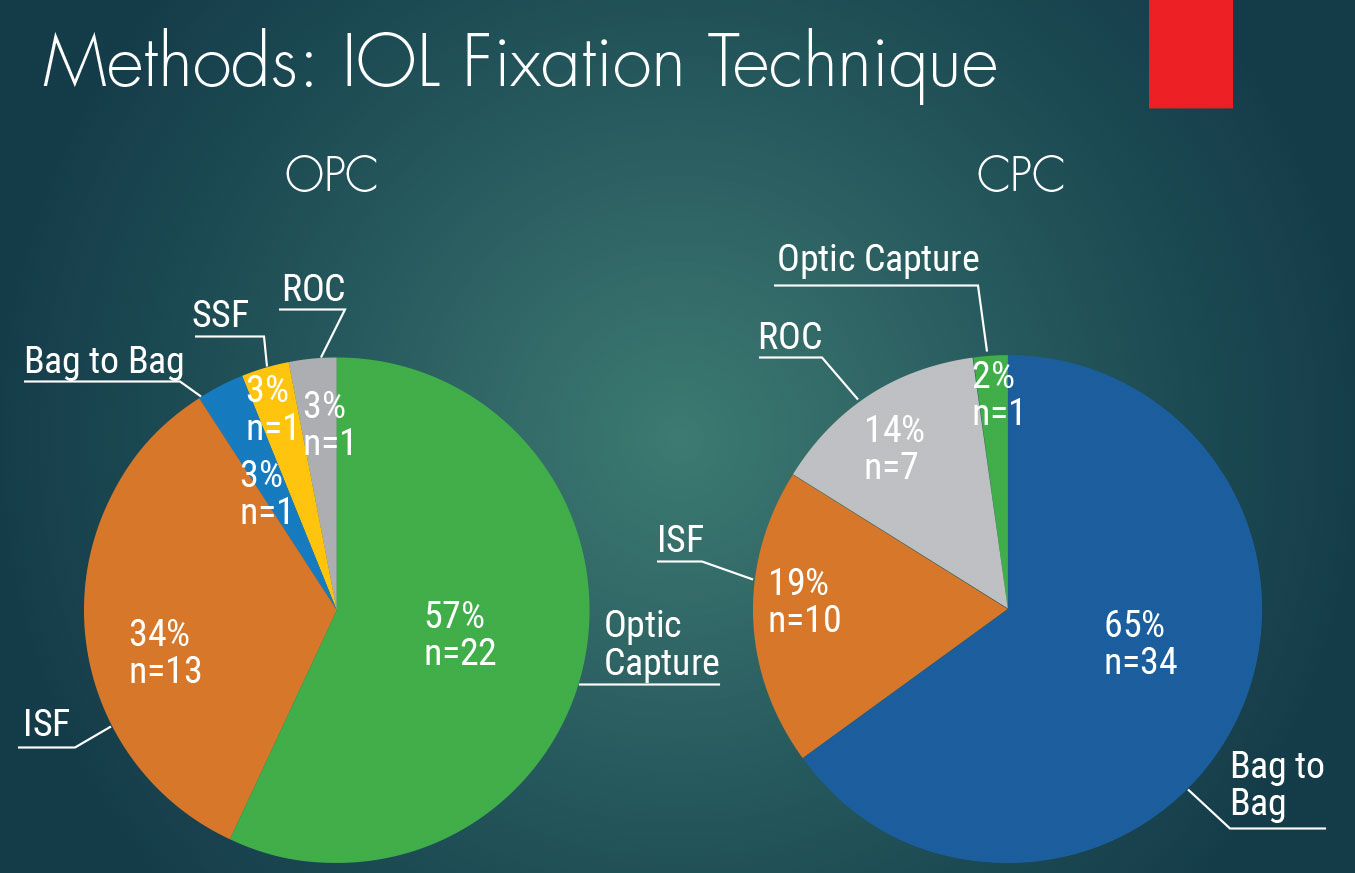

Figure 1. Data shows the primary methods of IOL fixation in both an OPC and CPC. In the OPC group, optic capture was the primary method, while bag to bag was used in a majority of the CPC group. |

“At Advanced Vision Care, we have had many patients referred for cases with malpositioned lenses or malfunctioning lenses. We consider optical problems, dysphotopsias, etc., to be malfunctioning lenses,” says Dr. Masket. “Patients’ dysphotopic symptoms may be severe and debilitating, impacting their quality of life. They felt and we believed that we could and should take the risk to exchange the symptom inducing lens for them. We gained significant experience.”

For this reason, Dr. Masket’s and his colleagues’ experiences led them to believe that there’s a misconception among surgeons that people who’ve had a posterior capsulotomy are at greater risk if an IOL exchange is performed, greater than those with intact capsules and, as a result, are forced to tolerate the undesired optical outcomes of surgery.

“Among the reasons for this long-held belief is that, typically, one can’t reopen the capsule bag and put the new lens back in the same space where it was held. That’s true under the great majority of circumstances,” says Dr. Masket. “Perhaps that’s what has led the profession, and in turn the lay public, to believe that once a capsulotomy is performed, there are no good opportunities for IOL exhcange.”

We spoke with Dr. Masket and Mr. Alsetri in the days after the AAO meeting to find out more about what their study revealed and how it may influence other surgeons to consider their data.

Study Methods and Outcome

The retrospective study included 90 eyes that met their strict inclusion criteria. Any eyes undergoing IOL exchange due to IOL malposition, dislocation or subluxation were excluded, as well as eyes with preoperative uncontrolled inflammation, glaucoma or a visual potential worse than 20/40.

“We only wanted the indication for the exchange to be for optical considerations so we could attribute any complication after the exchange to the exchange itself,” says Mr. Alsetri. “We didn’t want to muddle our data with any complications that could have occurred because of the condition of the eye before the surgery or because of a dislocated lens as well.”

|

|

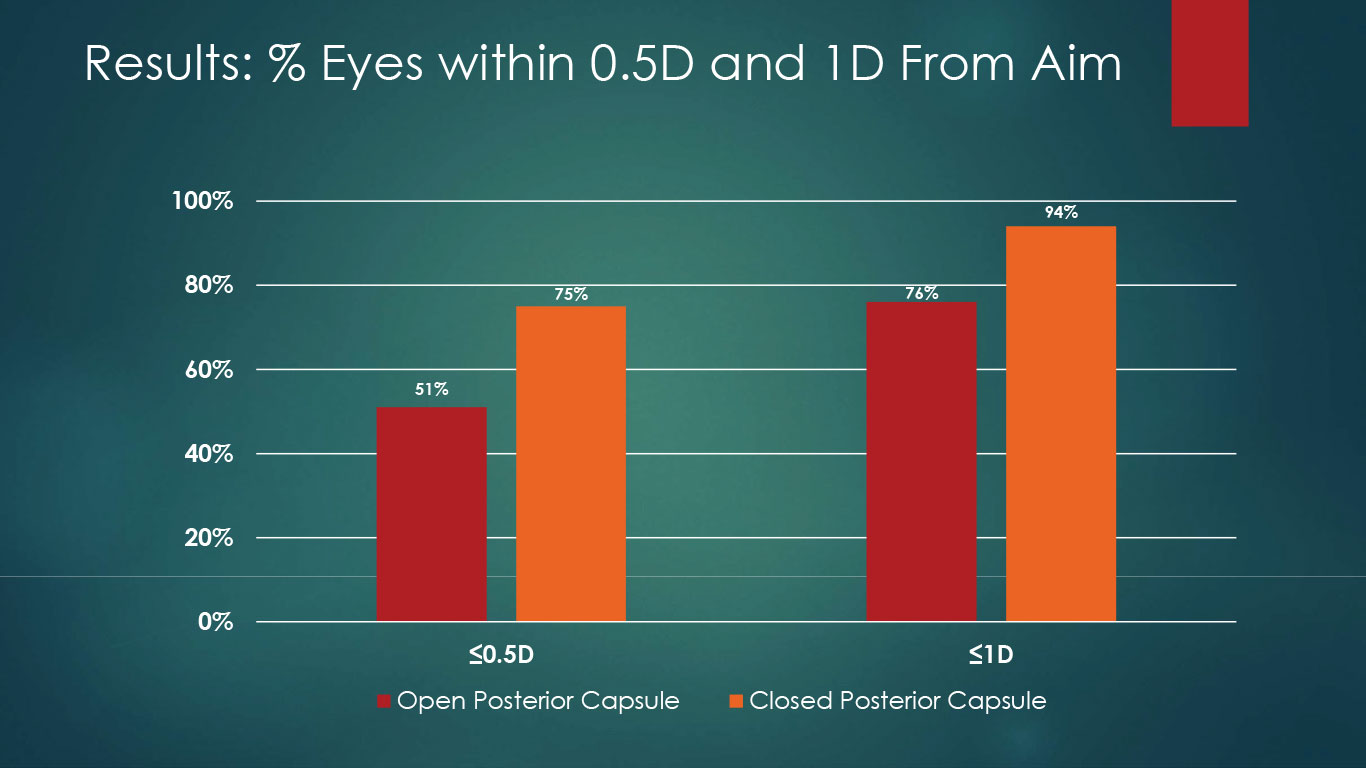

Figure 2. In the OPC group, 51 and 76 percent of eyes were within 0.5 and 1 D target, respectively. In the CPC group, 75 and 94 percent of eyes were within 0.5 and 1 D of target, respectively. |

The absence of ocular comorbidities in the study population is what makes this so unique, adds Dr. Masket.

“There were no malpositioned lenses, no bleeding, no complications from prior surgery. The only problems were related to the optical function of the existing IOL; this would include a diffractive optic dysphotopsia, negative or positive dysphotopsia, an opaque lens, or Z syndrome with Crystalenses.

“What was unique about these patients was that they all had good visual acuity, but all had intolerable symptoms related to the nature of the lens. No study has looked at this before,” Dr. Masket says.

“There is far less literature but more misinformation about the risks related to exchanging a lens with an open capsule. We believe that this study gives confidence to the patient that they can be helped and confidence to our colleagues that with proper surgical technique, these cases can gain relief from their intolerable optical side effects of lens-based surgery.”

The main safety outcomes included:

- postop IOP control;

- was their best corrected vision affected by the surgery;

- need for glaucoma drops or procedure(s) to manage postoperative IOP;

- presence of postop retinal edema or anterior chamber inflammation;

- presence of retinal tears or detachments;

- presence of corneal decompensation or edema; and/or

- presence of visually significant vitreous hemorrhage.

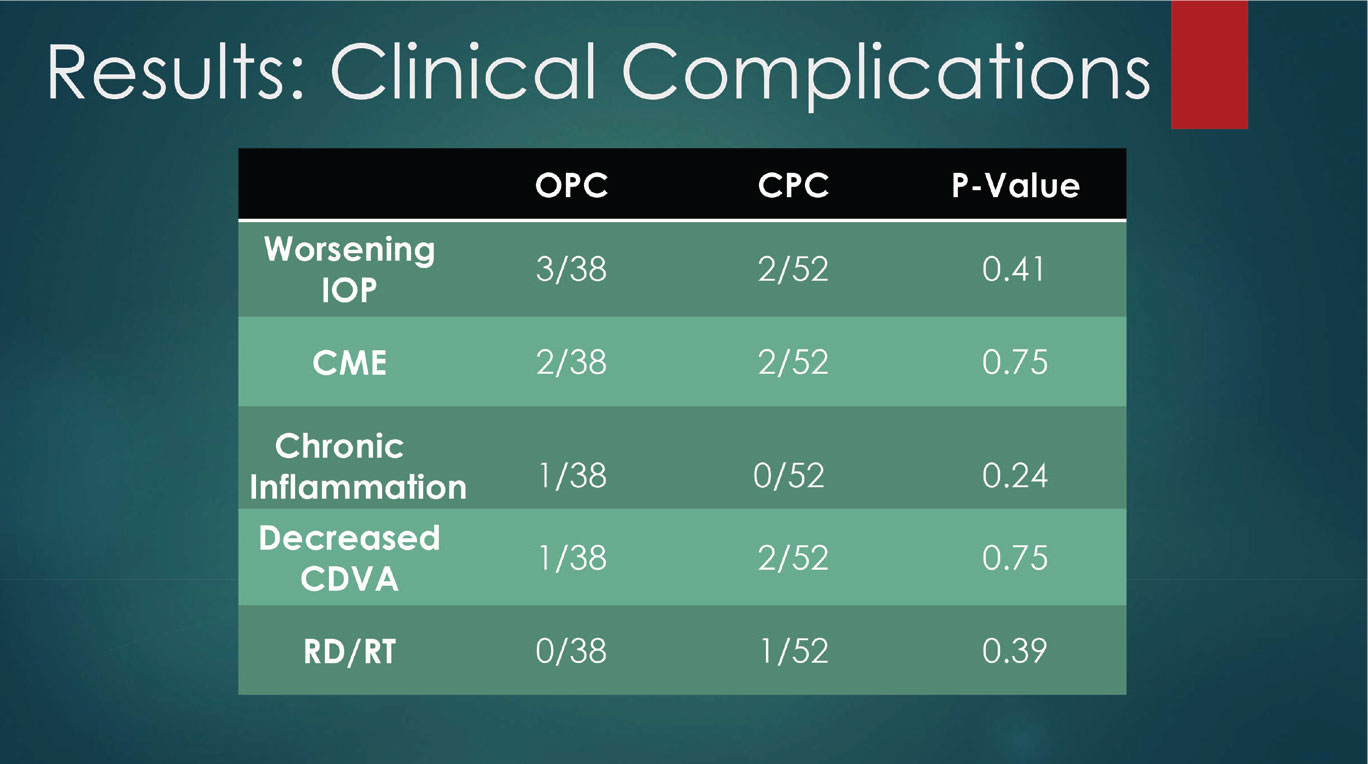

“We looked at all of these factors after surgery, and compared them between the two groups,” Mr. Alsetri says. “We found that there were no clinically or statistically significant differences between them.”

In fact, adds Dr. Masket, complications were fortunately low in both groups (Figure 3).

“That gives us more confidence that if the surgery is done pristinely then we can expect similar safety profiles when we’re looking at an IOL exchange regardless of the status of the posterior capsule,” Mr. Alsetri says.

The method of fixation for the majority of secondary IOLs was by optic capture in the open posterior capsule group versus bag-to-bag exchange in the closed posterior capsule group (Figure 1).

Secondary outcome measures were postop refractive error. In this area, the research did reveal some differences between the groups.

“The one difference that we did encounter was not in regard to complications or final best corrected visual acuity, but in the uncorrected visual acuity, because we found that we were less accurate in predicting the correct IOL power for the secondary lens in the group that had open capsules,” says Dr. Masket.

“We looked at their spherical equivalent after the surgery, and compared it to our pre-surgery intended aim,” says Mr. Alsetri. “We did find both a clinically and statistically significant difference between the two groups in that regard. Our mean difference from aim was -0.7 D in the OPC group, and just -0.41 D in the CPC group.”

This emphasizes the importance of setting expectations with the patient, Mr. Alsetri continues. “The surgeons at Advanced Vision Care always have that conversation with patients at the beginning to explain that their best corrected vision is going to be with glasses if they have an OPC, because we can’t guarantee the refractive outcome.

|

|

Figure 3. The study found no statistically significant difference in postoperative complications when comparing the two groups. |

“A lot of these patients opted for diffractive optic lenses at initial surgery as a solution to their presbyopia and now those lenses are being exchanged for standard monofocal lenses. They’re losing the benefits of the lens technology that was initially implanted, as well as the associated negative optical symptoms after the exchange. That can be disheartening to the patient if it’s not explained beforehand,” Mr. Alsetri says.

“Cataract or lens-based surgery is often erroneously compared by the lay public to LASIK outcomes. We can’t be as accurate as LASIK by any stretch of the imagination,” Dr. Masket chimes in. “Patients do need to understand that, while they may have been free of glasses with their multifocal IOL, they may need glasses in some form with the new monofocal IOL.”

He adds that there are literature references that agree that secondary IOLs aren’t as accurate with regard to optical outcomes as in-the-bag IOLs because the lens power formulae were designed for an in-the-bag IOL. “We don’t have refined formulas for lenses that are either fixated to the iris, fixated in the sulcus or scleral fixated, and so we extrapolate based upon how far anterior we think the lens will sit under those circumstances.”

What This Means for the Field

Dr. Masket says this study reinforces the feeling he had about patient outcomes. “I sense that this is an important investigation that Mr. Alsetri’s mined data has brought to light and we feel that there is a strong safety profile for IOL exchange,” he says.

Although Dr. Masket and his colleagues are confident in advising patients not to be overly concerned about the added risks of an OPC IOL exchange, they feel the procedure’s safety profile could be further boosted by additional data.

It’s also important to note the experience level of the surgeons whose data was analyzed. This point was raised during the paper presentation session at AAO, Mr. Alsetri says. “The moderator, Nick Mamalis, MD, said results may differ ‘in the hands of mere mortals,’ which is to say that exchanges haven’t always had the best results when it comes to inexperienced surgeons and the open posterior capsule. So there’s definitely a learning curve and a comfort and competence level that’s appropriate to achieve the results that we’re discussing right now,” Mr. Alsetri says.

On an even larger scale, Dr. Masket wants these results to give hope to patients suffering from dysphotopsias and similar symptoms, despite having a successful surgery initially.

“Patients can be highly distressed by dysphotopsia and similar symptoms, yet the eye can be anatomically pristine after surgery that mave have been done beautifully; this is frustrating to surgeon and patient,” he says. “Among the very first things that we tell patients is that if it comes to it, we expect that we can help them surgically. I think it’s very important to let patients know that their life is not over, so to speak.”

Dr. Masket is a consultant and investor for CAPSULaser and Haag-Streit. Mr. Alsetri has no financial disclosures.