Prostaglandin analogues have become a mainstay of glaucoma treatment, for good reason; they’re quite effective at lowering intraocular pressure and don’t require multiple applications each day. Until recently, it seemed like the downsides of this class of drug were minimal, making it a good choice for many patients.

Now, however, it’s become known that another side effect has been staring us in the face—literally—all along. Apparently, for biochemical reasons, there’s an affinity between the prostaglandin drugs and peri-orbital cells, in particular the fat cells. Exposure to the prostaglandin affects their metabolism, causing them to shrink. The shrinkage of the fat cells surrounding the eye causes enophthalmos—the eye becomes more sunken-in. The result is a deepening of the superior eye lid sulcus, while periorbital fat tissue seems to melt away. The cosmetic change—once you know to look for it—is actually quite striking, especially when a patient is using a prostaglandin unilaterally, which ends up causing asymmetry between the eyes.

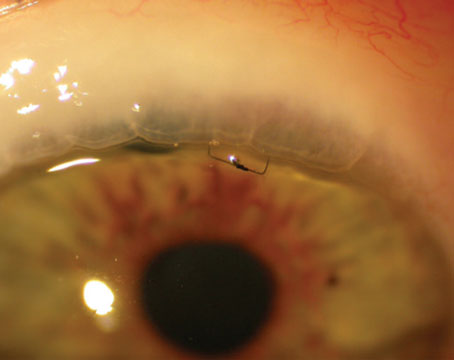

The effects produced by the use of a topical prostaglandin include upper lid ptosis; deepening of the upper lid sulcus; involution of dermatocholasis; periorbital fat atrophy; mild enophthalmos; inferior scleral show; increased prominence of lid vessels; and tight eyelids. This constellation of findings has been called prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy, or PAP. Technically, you could probably include all the other known side effects (e.g., lengthening of lashes and increased pigmentation of the iris and periorbital skin) under that umbrella, but this is of interest precisely because it’s gone unnoticed for so long.

It’s important to note that exposure to prostaglandins doesn’t kill fat cells or reduce their number. In fact, people have the same number of fat cells in their bodies their entire adult lives. When a person becomes fat, the fat cells have simply gotten fatter, and when a person becomes thinner, the fat cells have shrunk. So the change is caused by an alteration of the fat cells, not by their elimination.

Hiding in Plain Sight

The first patient that brought this to my attention was using a prostaglandin in one eye only; he asked me why his lid on that side was drooping. When I looked closely I realized it was only drooping a little bit, but his eyes displayed a lot of asymmetry because the lid sulcus was so much deeper in that eye. I was able to measure and photograph that he had enophthalmos, which suggested that this was an issue of fat atrophy.

|

Once I became aware of the phenomenon, I started taking photographs before initiating treatment. When a patient is trying a prostaglandin for the first time I usually do a monocular trial to test the efficacy of the drug. When these patients came back three weeks later, I could already see, and was able to document, full-blown PAP. That amazed me; I thought it would take months or years before you’d see these changes. Then, if I told the patient to stop the drops and return in three weeks, the PAP was completely resolved. Again, I was really surprised. Based on what I’ve seen, however, I suspect that if someone uses a prostaglandin for several years, even if they stop the drug they may not get total resolution. Some of the changes may be permanent.

Searching the Literature

Initially, I thought I was the first to notice this effect. I couldn’t find any mention of it in the package inserts, on company websites or in any of the journals I read. Eventually, though, I discovered that several articles had previously been published documenting this phenomenon. The earliest article was published in an optometry journal in 20041; the authors reported observing two cases of eyes becoming deep-set after using bimatoprost (Lumigan 0.03%). Other articles later appeared in journals published in other countries. The first report of this made by an American ophthalmologist was an article published in Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in 2008 by Louis Pasquale, MD, chief of glaucoma services at Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary, and his colleagues, including lead author Theodoros Filippopoulos, MD, who was a glaucoma fellow with Dr. Pasquale at the time.2 They observed this problem as a side effect of bimatoprost.

All of the early articles reported cases involving bimatoprost, which might lead one to conclude that the problem is limited to that drug. It wasn’t until the fifth article in 2009, from Japan, that travaprost (Travatan) was reported as causing two cases.3 Meanwhile, in my own patients I found that this change was occurring in those using any prostaglandin, so I believe it’s safe to say that it’s an issue with the entire class of drugs rather than being unique to any one of them. Of course, there could be differences in how this side effect occurs within the class; it may be a more prominent effect with one drug than another. I have patients who are only on latanoprost (Xalatan) who have full-blown PAP. Hopefully, future studies will determine whether significant differences exist between the prostaglandins. (Dr. Pasquale and his colleagues at MEEI have recently completed a longitudinal, cross-sectional study of PAP that will be presented as a poster at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting this year.)

How Did We Miss It?

How is it that such a readily visible phenomenon escaped our attention for so long? Most of us are very observant, so that was one of the first questions that occurred to me: How could this have gone unrecognized for so long?

|

Another point is that the majority of these patients use these drops bilaterally. When a patient uses a prostaglandin bilaterally, asymmetry doesn’t develop, and changes that occur over time are more easily missed or blamed on factors such as aging. And of course, we don’t see most of these patients every day, so small changes in appearance are easy to overlook. Even when the changes are noticeable—and in some cases they are—if you have no reason to believe the changes are connected to your treatment, you’re unlikely to make the connection.

Now, of course, I look for PAP in all patients and include it as part of my findings. If someone is on a prostaglandin drug, I’ll grade the PAP that exists just as I would any other clinical finding. For example, I might note “3+ PAP, left eye,” or “mild PAP OS,” in the chart.

Consequences of PAP

Obviously, altering someone’s appearance—potentially in a negative way—is not an insignificant thing. For that reason, being aware of this issue has definitely affected the way I choose a first-line, pressure-lowering drug. In the past, when I was not aware of this issue, I would almost always opt for a prostaglandin as the first-line drug for most patients. Today, I’m less likely to use a prostaglandin if a patient only needs to be treated in one eye, because of concerns about unwanted cosmetic changes. Not only is the patient likely to have longer lashes and darker skin unilaterally, but the treated eye will become more deep-set and the appearance of the lids will become asymmetrical. If a patient uses a prostaglandin bilaterally, at least it will affect both eyes so the patient won’t end up with an asymmetric appearance.

There are other potential negative consequences as well. For one thing, making the eye more sunken can make it harder to examine. Deep-set eyes are much more of a challenge, so this side effect may put us at a disadvantage in our efforts to help the patient.

In addition, asymmetrical appearance can trigger unnecessary medical testing by other doctors. If an individual is using a prostaglandin in one eye only, the resulting asymmetry may lead other doctors to question the reason for it. Those doctors might reasonably believe that one eye is bulging more than the other (even though the prostaglandin eye is actually becoming more sunken in). In theory, a bulging eye could imply a thyroid disorder or a tumor behind the eye. This could instigate a whole line of questioning and a medical workup, which has in fact happened; patients have undergone CAT scans and MRIs as doctors tried to determine why the eyes were asymmetric. If doctors were aware that this can be a consequence of using a prostaglandin in only one eye, many patients—and the health-care system—could be spared unnecessary testing.

It’s also important to realize that this effect will occur even when the drug is only being used for cosmetic purposes, as when it’s prescribed as Latisse (bimatoprost 0.03%). Beyond the desired effect of lengthening the lashes, the eyes may become more sunken; some patients may look better, but some may look worse. I’ve seen lectures promoting Latisse given by doctors who were not aware of this side effect. Clearly, any time a medical professional prescribes a drug, knowing all of the side effects is crucial. And, as already noted, even doctors who don’t prescribe the drug need to know about this to prevent unnecessary testing and scans in search of an explanation for the asymmetry.

|

However, if patients don’t have loose, puffy skin and their eyes are fairly deep-set to begin with, their eyes may become even more deep-set. Young people, for example, tend not to have a problem with puffy skin and may already have deep-set eyes. If you give these drops to young people, their eyes may go from being deep-set to being very deep set. This effect, along with darkening of the periorbital skin, can give them a “zombie” look.

Manufacturer Response

Based on suggestions from myself, Dr. Pasquale, and Dr. Wiley Chambers from the Food and Drug Administration, most manufacturers have added a sentence to their package inserts in the post-marketing experience section. For example, most inserts for topical prostaglandin drops now mention “reports of periorbital and lid changes associated with a deepening of the eyelid sulcus.” They don’t list this under the adverse reaction or side effects sections, because this was not officially noted during any of the clinical studies performed for the FDA.

Despite the mention in package inserts, the inclusion of this important piece of information is inconsistent in other places. In full-page ads placed in journals and other magazines, it is often not listed. I have recommended, and continue to recommend, the consistent inclusion of this important side effect in all written and verbal information about these drugs. I have also suggested that the companies send a mailing to all medical professionals informing them about this.

|

Of course, this “downside” to prostaglandins could also have a monumental upside. This property of the drug could lead to an entirely new, potentially even more lucrative use for the drug: shrinking fat cells not only around the eyes, but in other parts of the body as well. I have already made this suggestion to several of my patients being treated for glaucoma bilaterally with prostaglandin drops: Rub any excess drop that exits the eye into the upper and lower lids, and improved cosmesis will start to occur within weeks. I offer the opposite advice for patients with deep-set eyes: Be vigilant about absorbing the excess prostaglandin drop with a tissue, to avoid absorption by the periocular fat cells.

Implications for the Clinic

In terms of using this information in the clinic, probably the most important piece of advice I can offer is to simply be aware of the problem when you’re deciding what to prescribe. Look at the state of the patient’s lids and take that into consideration when choosing an option. Should you use a prostaglandin first in this patient, or a different class of drug? Should you consider not using a drug at all, perhaps opting for selective laser trabeculoplasty or surgery instead?

Clearly this is especially important if you’re planning to treat unilaterally, which may cause the patient to develop an asymmetrical appearance. (That can be a problem even if the overall effect makes the eye look better.) Patients should be aware of this possibility, just as they should know that the drug might change their eye color—an effect that some patients don’t mind, but others do. If the patient will use the drug in both eyes, you should still have the discussion, even though asymmetry won’t be an issue. Both eyelids will look less puffy and more deep-set, which may or may not be a good thing, depending on how the eyes look pre-treatment.

If you really want to monitor changes, the best way is with photography. Taking photographs at the outset is an option and is easy to do, though it’s certainly not mandatory. When I was first noticing this, I was very interested in it, and I took lots of external photographs. (Bear in mind that the patient must give written consent for medical photography—especially if you want to use the images for presentation or publication.)

In terms of patients who are already on treatment, I think doctors should be trying to observe whatever changes are taking, or have taken, place. Document the effect either by describing and grading or by photography, and note it in the medical record. Patients who develop PAP may elect to continue or discontinue the drug. Those who have cosmetically-bothersome orbital fat atrophy may wish to consult with an orbital plastic surgeon. (There are some treatments available, and this is an active area of investigation in the field.)

Now You See It…

The bottom line here is that although this has been very sparsely published, this effect is real, it’s common, and it’s associated with all the drugs in the class, including the generics. It’s now listed in the package inserts. And it can have significant cosmetic and structural effects that we should be aware of, should look for, should document, and should discuss with the patient, just as we would with any side effect of any drug. REVIEW

Dr. Berke is associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., and chief of the Glaucoma Service at Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow, N.Y.

1. Peplinski LS, Albiani Smith K. Deepening of lid sulcus from topical bimatoprost therapy. Optom Vis Sci 2004;81:8:574-77.

2. Filippopoulos T, Paula JS, Torun N, et al.Periorbital changes associated with topical bimatoprost. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;24:4:302-307.

3. Yang HK, Park KH, Kim TW, Kim DM. Deepening of eyelid superior sulcus during topical travoprost treatment. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2009;53:176-79.