Today’s phacoemulsification machines are packed with innovative features such as advanced fluidics and IOP control, all in the name of enhancing the safety and efficiency of cataract removal procedures. No two systems are exactly alike, however. In this article, we’ll take a look at several cataract surgeons’ techniques using different phacoemulsification systems and how the technological advances are making a difference.

Veritas (Johnson & Johnson Vision)

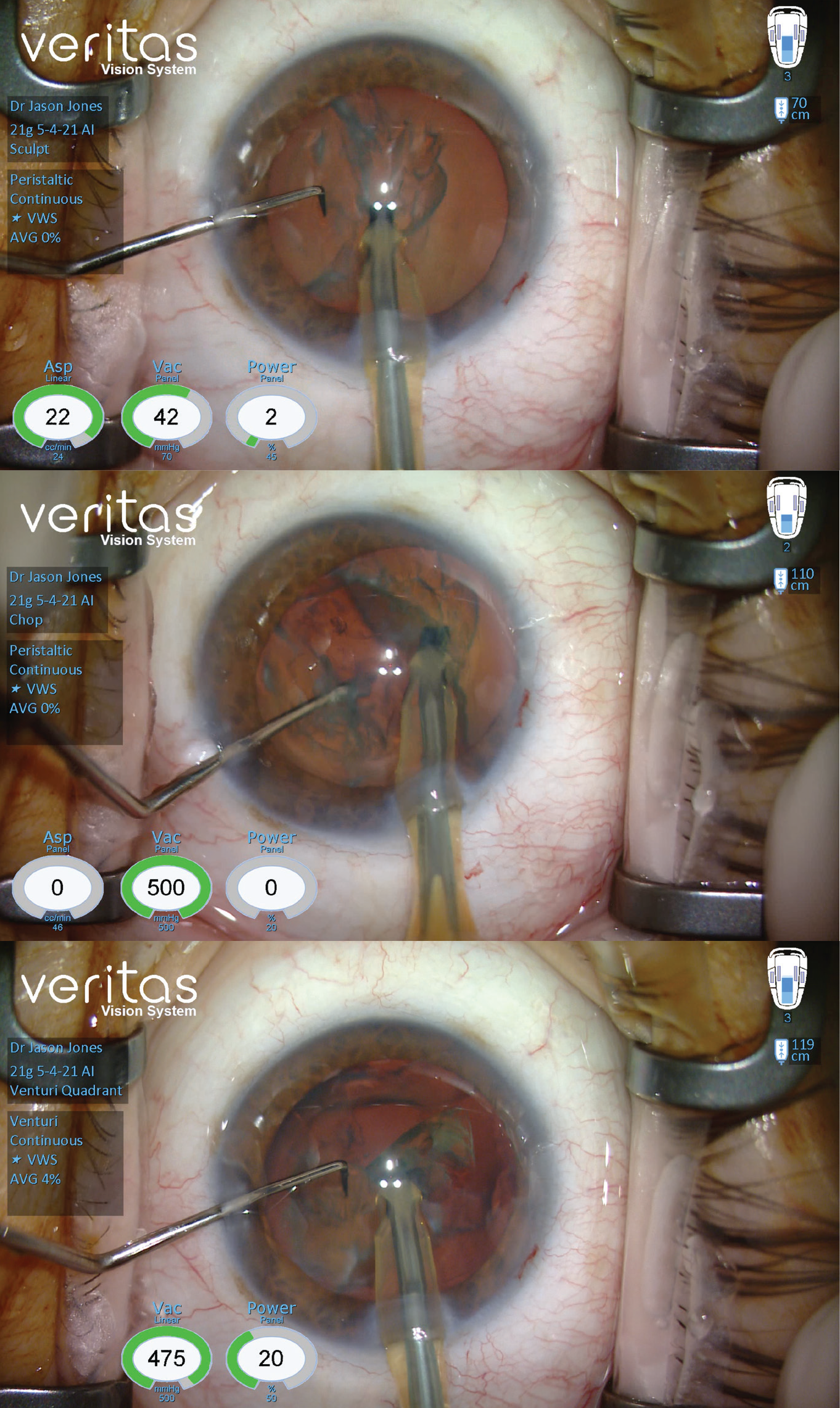

Jason J. Jones, MD, medical director of the Jones Eye Clinic in Sioux City, Iowa, has been using Veritas since its preliminary market release in early May 2021. With Veritas, he reports increasing his effective bottle height to around 115 cm for venturi quadrant removal, noting that “The forced infusion plus physical bottle height [during this stage] offers some extra stability.”

He says Veritas’ dual pump system is convenient, allowing him to easily switch between peristaltic and venturi. “I use peristaltic for my chop because it’s still very efficient for whatever I might need it for, whether that’s a dense or a soft nucleus,” he says. “If you’re on a venturi setting and have a very soft cataract, you still want to chop it. You need to be able to chop things with control, and then when those pieces are liberated, you want something with good response and very high performance.”

Dr. Jones also reports less fatigue using the new foot pedal, which has a flat rather than angled design.

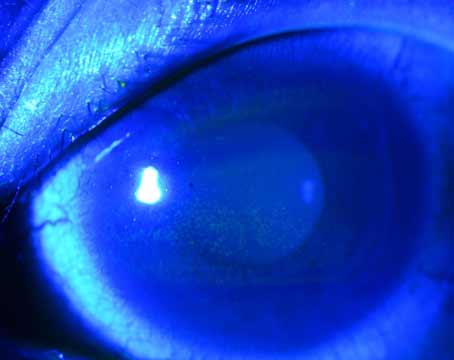

Dr. Jones shares his cataract removal technique with Veritas: He begins his cases by irrigating with lidocaine and epinephrine. Then he fills the anterior chamber with dispersive viscoelastic (Healon EndoCoat, Johnson & Johnson Vision) and stabilizes the eye through the paracentesis with his instruments. Next, he marks the cornea for centration. He makes his capsulorhexis using Utrata forceps and hydrodissects with a Chang cannula.

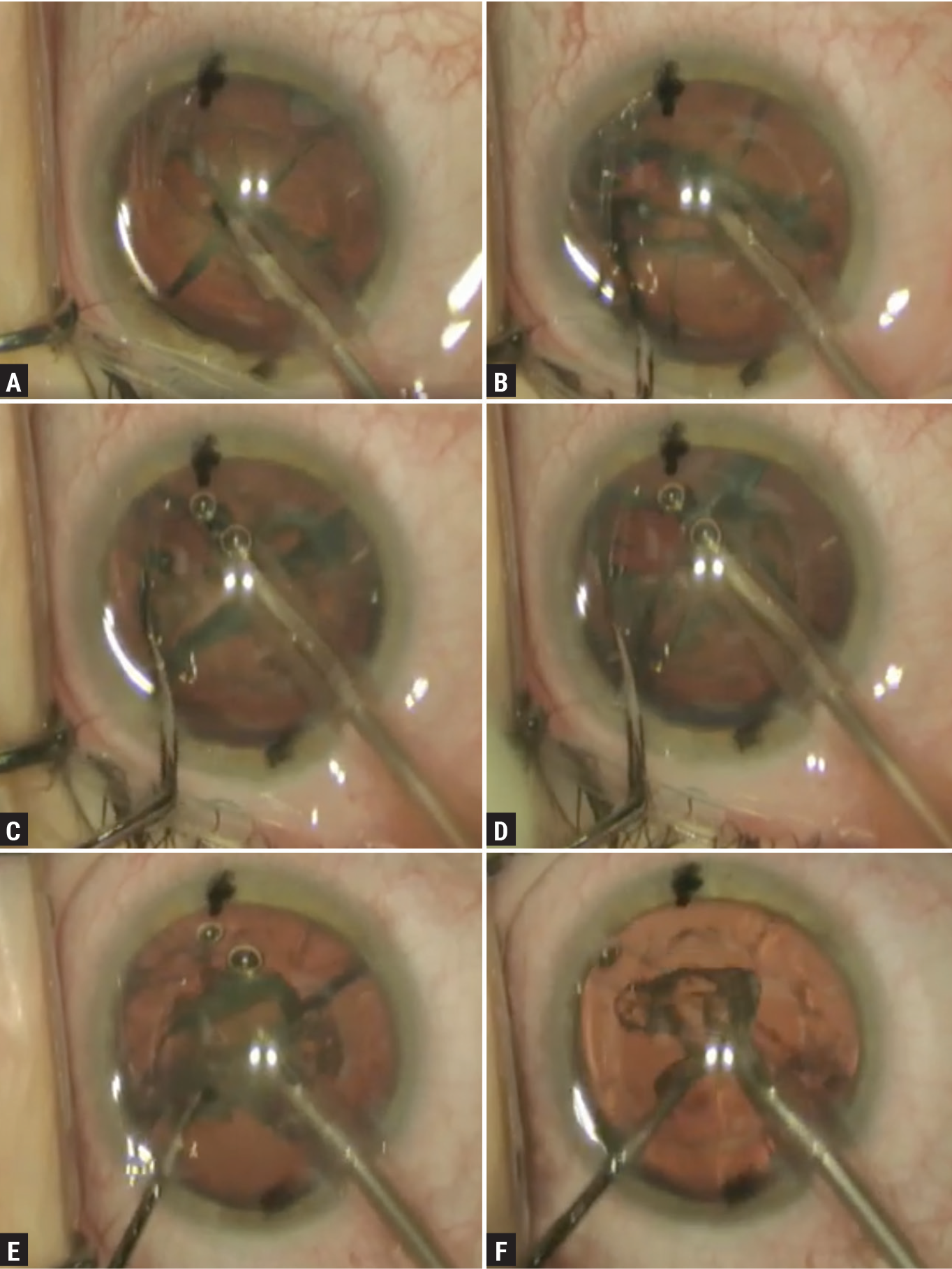

He begins cataract removal in the sculpt setting with fairly low vacuum and aspiration (Figure 1). “This is a peristaltic setting,” he explains. “I use it to clean off the anterior cortex from the surface of the nucleus within the capsulorhexis.”

|

|

Figure 1. Jason Jones, MD, performs cataract removal surgery using the Veritas (Johnson & Johnson Vision). Shown here: sculpt (top), chop (middle) and venturi quadrant removal (bottom). (Image courtesy of Jason Jones, MD) |

Afterwards, he switches to a chop setting (also peristaltic) and buries the tip. He listens for the machine’s pulsing sounds. “When you achieve an occlusion state, the sound becomes noticeably higher,” he says. “Veritas doesn’t give you an occlusion bell, but it’s very easy to listen for the level that indicates I have a grasp on a piece of cataract. The Veritas’ tones are more pleasant to listen to than those of previous machines—for me and for the patients.

“I then use a small amount of phaco energy to get in, and then I do a vertical chop,” he continues. “I maneuver my chopper away from me, plunge it into the nucleus and bring it toward my phaco tip. The crack will elaborate on its own. When the two devices come close to each other, I separate them while paying attention to a posterior separation, so it’s more of a pivot of instruments from their incision fulcrum than a translational movement. I want to get that crack through the posterior plane, but also subincisionally and distally from me.

“I now have essentially two nuclei to deal with,” he continues. “This typically helps to rotate the nuclei counterclockwise. I’ll usually do two more chops on each hemi-nucleus for a total of six pieces. As I rotate the nucleus around to get to the last piece, I’ll chop it while I’m still in occlusion holding.

“Then, I touch my button to advance, and go right into my venturi quadrant removal and start to take out pieces,” he says. “I use my chopper to help enucleate pieces out of the capsular bag, but typically they’re pretty well-liberated from each other as well as from the capsular bag, so they kind of tumble out pretty nicely. I rotate the second hemi-nucleus to the other side, away from me again, and complete the case of phacoemulsification.”

He adds that as he gets to that last piece, he switches from the vertical chopper to a more blunt instrument that he developed, which is on the other end of his chopper. “This way, if I need to touch the capsule or something comes close to it, it’s less risky from a safety standpoint. I rotate the chopper in my hand, put it back in the paracentesis and finish manipulation of it up to the phaco tip.”

He then switches out his second instrument and goes back in with dispersive viscoelastic. “I lay a stripe of viscoelastic in the anterior chamber,” he says. “To do that properly, I need to come down to foot-position zero because any irrigation is going to shoot the viscoelastic out of the wound. Basically, I replace the anterior chamber volume with viscoelastic. This provides better stability and nicer tension overall to the anterior chamber with less collapse.”

If he has any formed cortex left, he goes in with irrigation/aspiration and pulls it out in venturi mode. “Having remaining cortex is pretty uncommon—about 10 to 15 percent of the time I do need to get some small piece out of the capsular bag, but otherwise I go in with a silicone-tip cannula on a 5-cc syringe to irrigate and polish off the central posterior capsule,” he explains. “After that, I go in with a 27-gauge cannula 5-cc syringe and irrigate into the fornix of the bag.”

To eliminate any cortical remnants, he reenters the main wound and sweeps around to a 12 o’clock position. He says it’s reassuring to clean these chunks out since the iris obscures the view, hiding any leftover material. “I take the same 27-gauge cannula and go into the paracentesis,” he continues. “I go subincisionally over to my right; now I’ve done about three-quarters of the capsular fornix. Next, I go back with a Chang cannula 5-cc syringe, which isn’t like hydrodissection, but I use the angled cannula to go and clean the inferior subincisional fornix and sweep around to my incisional left to irrigate out 360 degrees of capsular fornix.”

He then puts in dispersive viscoelastic. “To inflate the capsular bag, I curette the capsular bag for lens epithelial cell removal from the subcapsular region of the anterior leaflet,” he says. After placing the IOL, he removes the viscoelastic with irrigation/aspiration.

“Be sure to rotate the lens and go behind it as well,” he notes. “I go under one side, rotate the lens and go on the other side. It’s amazing how often there’s a thin layer of viscoelastic still on the opposite side of the lens. It’s nice to get all of that out. Be sure to get all of the viscoelastic out of the anterior chamber as well. I irrigate into the fornices of the angle using a 27-gauge cannula, hydrate my wounds, check my incisions and ensure they’re dry, and then the case is completed.”

CataRhex3 (Oertli Instrumente AG)

|

|

Oertli’s CataRhex3 is portable and reliable, says Jack S. Parker, MD, who performs one-handed phaco and in-office surgery with this machine. (Image courtesy of Oertli Instrumente AG) |

Jack S. Parker, MD, PhD, of Parker Cornea in Birmingham, Alabama, says the Swiss-made CataRhex3, though unassuming in its appearance, is a highly dependable, safe and intuitive machine. “We originally purchased a CataRhex for mission trips to Nicaragua about 10 years ago,” he says. “It’s the size of a carry-on. It performed admirably on those trips.” Now, Dr. Parker uses his CataRhex3 for routine, in-office cataract surgery.

His approach with the CataRhex3 employs two techniques not commonly performed. First, he pre-chops the nucleus with a pre-chopper. “This allows me to divide the nucleus into two or four pieces prior to inserting the phaco handpiece into the eye,” he says. “It reduces the amount of total ultrasound energy in the eye.”

Secondly, Dr. Parker performs one-handed phaco. “I like to do phacoemulsification without a second instrument inside the eye,” he says. “There’s nothing usually there to help me grab pieces or keep the posterior capsule back. I believe that if you can just use the phaco handpiece, as opposed to the phaco handpiece and a secondary instrument, the chamber stability is a little better. The CataRhex3’s phaco tip is also larger than most others. This gives you a better ability to grip pieces.

“Many people prefer a second instrument because they’re worried about the posterior capsule trampolining up into the phaco tip,” he continues, “but what I’ve found using Oertli’s machine is that the chamber stability is good enough that you don’t necessarily need a second instrument in the eye. I feel that when all of my attention is just on the phaco handpiece and not divided between phaco and something else in the eye, it’s a more pleasant, safe and controlled experience.”

He says the machine employs only longitudinal, as opposed to torsional phaco. “This was a philosophical choice by the Oertli engineers,” he says. He says the thinking was that longitudinal phaco may be safer than torsional phaco because the tip “moves predictably back and forth and is less likely to cause inadvertent damage to surrounding structures.”

Additionally, the CataRhex3 is now available with Speep, Oertli’s pump innovation that offers more precise control of flow and vacuum, according to the company.

Dr. Parker points out that CataRhex3’s reliability offers peace of mind. “When I’m operating at the hospital, it’s not uncommon for there to be something wrong with a phaco machine, and we’ll have to bring in another and set it up,” he says. “We don’t have a backup for the CataRhex3 in our office; we just have extreme confidence in its performance. It’s very straightforward—no touch screens, color interfaces, error messages or boot-up screens. We just flip a switch and it’s ready to go.”

Centurion (Alcon)

Brian M. Shafer, MD, of Chester County Eye Care in Malvern, Pennsylvania, uses the Alcon Centurion with the Active Sentry handpiece. He says the new IOP-sensing technology in the tip of the handpiece offers greater safety for preventing post-occlusion surge.

“The Centurion system complements my approach well,” he says. “Active Fluidics and Active Sentry allow me to adjust the pressure by clicking a button rather than waiting for the bottle to change its physical height. It’s safer, and it also benefits beginner surgeons since chamber stability isn’t as guaranteed based on technique.”

He says he employs either a divide-and-conquer (about 90 percent of the time) or a stop-and-chop technique, depending on the type of cataract he’s faced with. “I have many different settings depending on what I experience intraoperatively with each unique cataract,” he says. “The Centurion allows for a lot of adaptability based on the lens itself.”

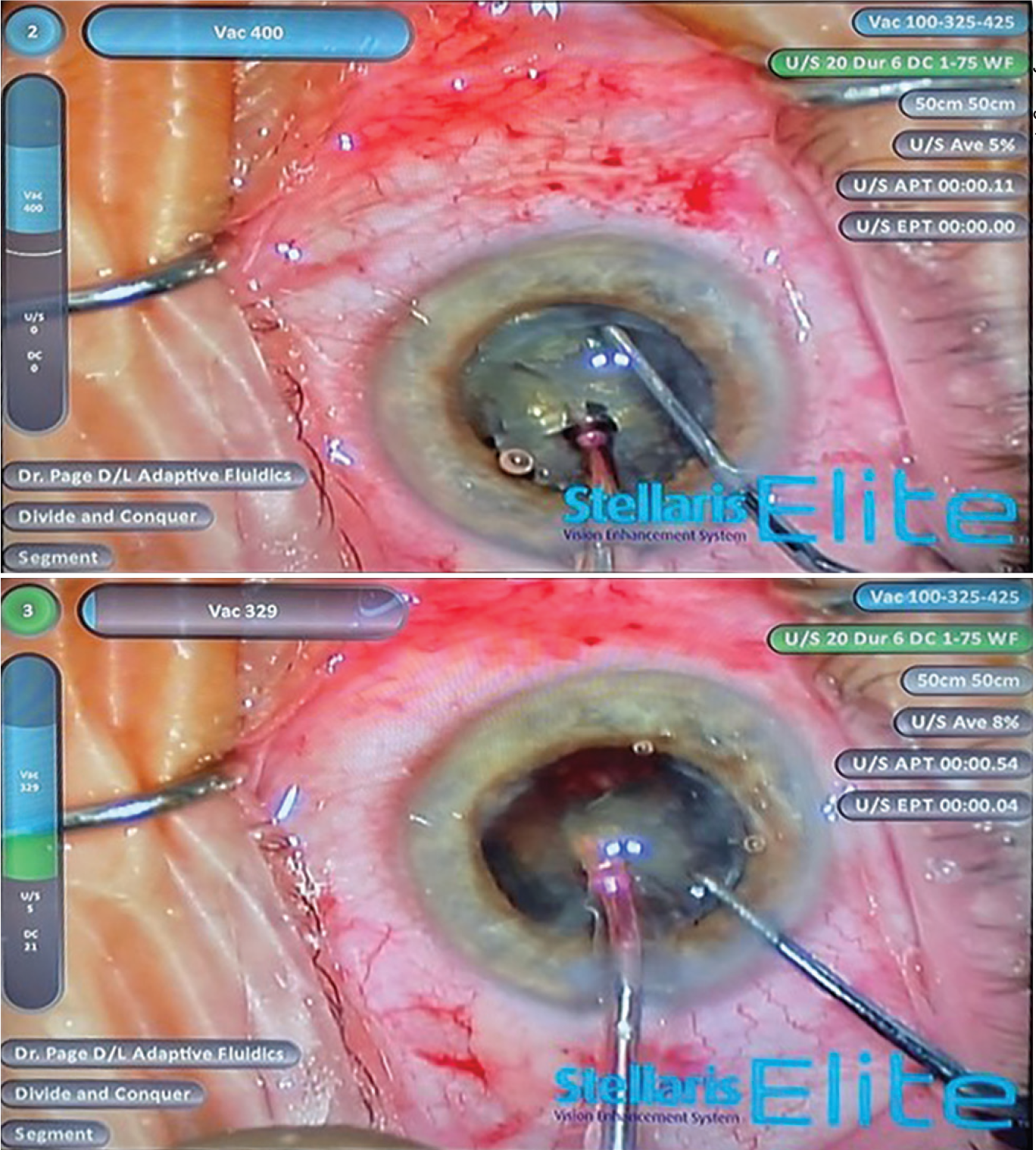

Dr. Shafer shares his approach: “After completing a capsulorhexis and hydrodissection, I begin my standard divide-and-conquer technique by rotating the nucleus 360 degrees to ensure complete movement,” he begins. “Next, I set my phaco setting to sculpt, which provides high phaco power, low vacuum and a low flow rate (Figure 2). This allows for a lot of energy to be delivered directly to the center of the nucleus without displacing it too much. I sculpt deeply, and then I use a second instrument to crack the nucleus. Using the second instrument, I spin the nucleus 90 degrees and continue to sculpt into that second hemisphere. I crack it into a quadrant, spin it 180 degrees, sculpt again and crack it. I’m left with four quadrants.”

|

|

Figure 2. Using the Alcon Centurion, Brian M. Shafer, MD, demonstrates center sculpting (A), cracking the nucleus into two hemi-pieces (B), cracking the first hemisphere into quadrants (C), cracking the final hemisphere into quadrants (D), emulsifying the first quadrant (E) and emulsifying the final quadrant (F). (Image courtesy of Brian M. Shafer, MD) |

At this point in the procedure, he switches his settings to ultrasound 1 on the Centurion. “This setting has a higher flow rate, higher vacuum and slightly lower phaco power,” he explains. With a second instrument he gets behind a quadrant and shifts it into the center portion of the capsular bag. He maintains occlusion of that quadrant using fluidics and ensures it stays in the proper position during emulsification with his second instrument.

After the first quadrant is completely emulsified, he moves on to the second quadrant. “I use the second instrument to position the quadrant toward my phaco tip,” he says. “Maintaining the ultrasound 1 setting, I emulsify that piece as well. Then I spin the nucleus around and do the exact same thing with the final two quadrants.”

He says that it’s often difficult to achieve a good crack on certain lenses, such as the softer ones. For these cases, he switches to a stop-and-chop technique with a soft-chop. “When I start out my technique, I still begin by sculpting in the center using the same approach as described above, but instead of making four quadrants, I spin the nucleus so I have two hemispheres. I reach my second instrument around, beneath the anterior capsule, and I go to the equator of the lens and do what I call a soft chop.”

For Dr. Shafer’s soft chop, he impales the hemisphere with his phaco tip, brings his second instrument to the phaco tip and makes a soft, horizontal chop with no phaco power engaged. “That divides the hemisphere into quadrants,” he says. “I spin it around and do the same thing with the other hemisphere.”

With a soft lens, he says the epi-nucleus setting is better suited than ultrasound 1. “The epi-nucleus setting has a higher vacuum rate, slightly lower flow rate and lower phaco power,” he says. “This allows for maintaining excellent occlusion while aspirating the quadrant with minimal phaco energy delivered. It’s just not necessary to emulsify that piece.”

For very dense lenses, he switches to his dense setting, which increases the amount of phaco power delivered to the cataract. “Greater phaco power is important to ensure you can cut through a very dense lens,” he says. “In other circumstances, if the lens is pretty hard or if I just don’t have my usual equipment, I’ll use the chop setting.

“Most of my technique uses a combination of longitudinal and torsional power at the phaco tip,” he continues. “I use a lot of torsional power when breaking up my lenses using the divide-and-conquer technique, but if I’m going to chop, I switch to a longitudinal technique to drive the phaco tip into the center of the hemisphere. Then, I use very high vacuum (around 400 to 500 mmHg) with no phaco power being delivered, and I pass my second instrument to complete either a vertical or horizontal chop. I don’t do that too often anymore, but I do have that setting available if the situation presents itself.”

Stellaris (Bausch + Lomb)

Timothy Page, MD, in practice at Oakland Ophthalmic Surgery in Birmingham, Michigan, and Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan, says the Stellaris is well-suited to the chop technique because of its exceptional holding power and fluidics that prevent post-occlusion surge.

“It’s a high-performance phaco system,” he says. “The micro-phaco needle has an hourglass design. The lumen is very small, and this offers greater visibility, especially when performing complex cases. It tapers quickly from a diameter of about 790 µm to 500 µm. This small diameter acts as a flow restrictor, preventing large boluses of fluid from rushing out of the eye instantaneously.”

Dr. Page’s main technique is a vertical chop. “The Stellaris needle has a nice, flared tip, which gives me a lot of surface area to engage the nucleus,” he says. “I hold the nucleus in place in foot-position two with my foot pedal and use the chopper to do a vertical chop technique. I create two hemispheres and then make my first quadrant.”

He says removing the first quadrant from the capsular bag is usually the most difficult, but the Stellaris’ dual-linear function helps to facilitate this maneuver (Figure 3). “The dual-linear foot pedal enables you to swing your foot to the left or right, depending how you program it, so you can get extra vacuum to pull a piece of cataract out of the capsule and into the safe zone,” he explains. “It helps to reduce the gradient between very high pressures in the eye during occlusion and low pressures when the occlusion clears. I often apply an extra 100 mmHg of vacuum this way. Then, I’ll go back in my linear phase and emulsify the nucleus using only 30-percent phaco power and 300-mmHg vacuum. The Stellaris uses venturi, which is highly efficient.”

|

|

Figure 3. Timothy Page, MD, says that the Stellaris’ (Bausch + Lomb) dual-linear function allows the surgeon to increase vacuum when needed, such as during removal of the first quadrant, which is made easier with higher vacuum (top). Once the quadrant is in the central safety zone, he lowers the vacuum level (bottom). In the pitch position, the pressure gradients and the risk of surge are reduced. (Image courtesy of Timothy Page, MD) |

For dense cataracts, he increases his phaco power to about 40 to 50 percent. However, he notes that this setting won’t necessarily translate to other machines, due to the Stellaris’ long stroke length. “When you’re at 50 percent on the Stellaris, you’re pulling a stroke length of about 70 µm,” he says. “The whole travel length on other machines may be about 80 to 90 µm at 100 percent; you don’t need the same amount of power on the Stellaris. The Stellaris also has a low oscillation rate at 28.5 kHz, which reduces the chances of phaco wound burn. I’ve rarely gone up to 50 percent on this machine.”

He adds that the disposable CapsuleGuard I/A handpiece with a silicone tip for cortex removal helps to ensure safety. “I’ve never ruptured a capsule using this handpiece,” he says. “The cannula is a good millimeter away from the port, so it’s highly unlikely that you could ever aspirate the capsule up far enough that it would touch metal and rupture.

“If you’ve wanted to use chop and master the chop techniques, but are having difficulty with a peristaltic system, I recommend trying the Stellaris because of its flared phaco needle and ease of holding the nucleus,” Dr. Page says. “The dual-linear function will help you hold everything in place and remove the first quadrant without having to use high levels of vacuum throughout the rest of nuclear disassembly.”

EVA Phaco-Vitrectomy System (DORC)

|

|

DORC’s EVA Phaco-Vitrectomy system has a redesigned footswitch with dual-linear function for independent control of aspiration and phaco during cataract surgery. |

The upgraded EVA system from Dutch Ophthalmic Research Centre enables cataract, vitrectomy and combined procedures. For cataract surgeons, the system features an integrated, redesigned footswitch, which the company says is easier to operate, and a modifiable foot bed so surgeons can choose their optimal foot position. The wireless footswitch is also dual-linear, allowing for independent control of and quick transitions between aspiration and phaco. There are eight programmable switches.

The system has a 19-inch touch-screen user interface, voice feedback, an integrated stylus holder and infrared remote control as well as multi-language functionality.

DORC says the EVA’s Vacuflow fluidics system with Valve Timing Intelligence (VTi) provides a three-times faster rise time (300 msec; 0 to 680 mmHg@0 cc/min 10 to 90 percent) than traditional venturi and reduces pulsations in peristaltic mode. Flow mode is 0 to 90 ml/min. EVA uses a gravity-based infusion system with an integrated IV pole.

EVA’s phaco pulse mode is 250 pps for phacoemulsification and fragmentation. Its oscillation rate is 40 kHz and its stroke length is 100 µm at 100 percent. EVA’s phaco system features needle detection, auto tuning and the company’s advanced fluidics technology.

No matter which machine you use, experts say it’s a good idea to enlist your company representative when adjusting to a new model. “Sit down with your company representative and go through some cases,” says Dr. Shafer. “For example, if you have too much chatter during quadrant removal, it’s often because your power is a little too high and it’s creating cavitation bubbles. Your company representative can adjust your power a little lower or increase your vacuum to ensure you maintain occlusion. Tell your representative what you’re experiencing and ask for their feedback. Everyone’s technique is a little different.”

Dr. Jones is a speaker and consultant for Johnson & Johnson Vision. He also does paid research and clinical studies for J&J Vision. Dr. Shafer is a consultant for Alcon. Dr. Page is a consultant for Bausch + Lomb and Johnson & Johnson Vision. Dr. Parker reports no relevant financial disclosures.