Review of Cornea & External Disease In this Issue... Artificial Intelligence for the Cornea Specialist by Christine Yue Leonard DSO and Cultured Endothelial Cell Transplants: A Review by Thomas John, MD, and Anny M.S. Cheng, MD Premium IOLs in Patients with Corneal Conditions by Asim Piracha, MD Diagnosis & Management of Blepharitis by Charles Bouchard, MD, MA |

POINT: KERATOCONUS IS PRIMARILY A REPETITIVE STRESS INJURY

Eye-rubbing is Key to Progression

While keratoconus likely has multiple causes, eye-rubbing contributes significantly to disease manifestation.

By Alan N. Carlson, MD

Durham, NC

The origins of keratoconus are incompletely understood, but they’re likely multifactorial, where keratoconus genetics create a predisposition and eye rubbing contributes to progression. Consider two identical twin brothers with identical genetics. One becomes an alcoholic and the other decides never to touch a single drink, yet still has a genetic predisposition to alcoholism. I believe this explains why only 7 percent of patients who have keratoconus have a family member they know of who also has keratoconus. There may be others in the family with the predisposition but who don’t rub their eyes.

We find that as keratoconus progresses, it takes less and less rubbing to impact the cornea and cause further progression. Patients may even get to the point where their disease is so advanced, it progresses without eye rubbing. Eye rubbing may play less of a role in some patients’ disease, but it’s clearly an impactful behavior in others.

This can be difficult to determine, however. Our ability to ascertain the degree of a patient’s eye rubbing through a history is often thwarted when the patients themselves fail to recognize and report their eye rubbing, which has become such an ingrained behavior it’s almost unconscious. Patients may underreport eye rubbing for a variety of reasons, perhaps due a lack of recognition or embarrassment. Family members present during the encounter often support a greater recognition of eye rubbing than the patient reports.

When both patients and family members can’t confirm eye rubbing, it’s often the case that the patient sleeps in a position that applies pressure against the eye with pillow or hand. In some cases, the patient may have been a vigorous eye-rubber as a child. I believe it’s possible to set the ball in motion from an early age. I gave a lecture on this topic a few years ago, and an optometrist reported that one of her keratoconus patients had videotaped her infant child in her crib. Sure enough, the baby was digging into her eyes non-stop.

The Signature Rub

For years we thought eye rubbing was related to the fact that keratoconus patients had a higher likelihood of having an allergy and would therefore rub the eyes to alleviate itchiness. However, there are features and motivations of a keratoconus eye rub that are distinct from an allergic eye rub.

The allergic rub usually falls on a lateral, x-y plane with a back-and-forth motion and moderate pressure, followed by the index fingertip rubbing more nasally and then at the caruncle to finish. These individuals tend to rub for only a short amount of the time (usually under 15 seconds) in an “itch-rub-itch” cycle. They report that it’s only to relieve itching and they wouldn’t rub their eye otherwise.

|

|

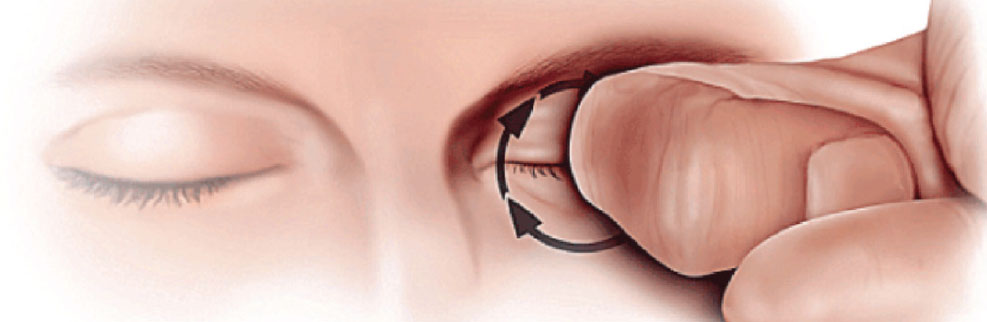

Figure 1. The KC patient will often use a knuckle to generate greater pressure through the center of the lid, applied with circular motion. |

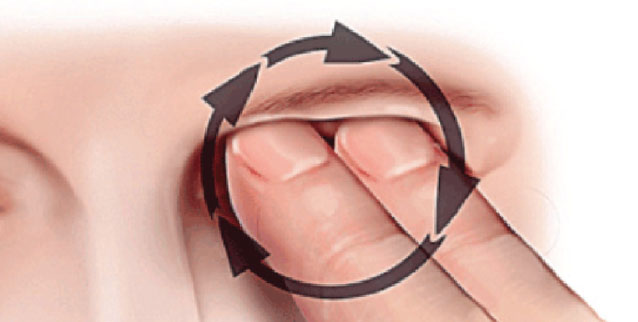

A keratoconus rub applies vertical pressure on the z-axis. These patients like to put direct pressure on the eyelid and rub in a circular fashion with a pointed instrument, such as a knuckle (the middle knuckle is more common than the distal or proximal knuckle) or fingertip. This might last for 10 to 180 seconds, and up to 300 seconds. Sometimes they just like to press on the eyeball through the eyelid.

Keratoconus patients are either unable to explain why they rub their eyes or report that there’s just something pleasurable about it. I liken this to scratching a mosquito bite. Scratching a mosquito bite feels very different than scratching an area on the body without a mosquito bite.

|

|

Figure 2. The KC patient may also generate intense central pressure by applying their finger tips(s) to the central lid, often with a circular motion. |

When asking patients about their eye-rubbing history, it’s important not to ask leading questions. For instance, I’ll say, “Show me how you rub your eyes,” and they’ll go up with both hands and rub their eyes. If they rub one eye, 80 percent of the time, that’s the side they sleep on and the eye with the worse keratoconus. Yes, sleeping position, too, can affect keratoconus progression.1

This is another behavior that patients often aren’t aware of. Certain sleep positions put pressure on the eyes, and over time the cumulative low-to-moderate pressure for several hours each night adds up. Many keratoconus patients even report that they can’t sleep unless something’s in contact with their closed eye such as their arm flung across their face if they sleep on their back, or a pillow if they sleep on their side or stomach. If their disease is advanced, you’ll often find they sleep on their stomach because they can press both eyes into something.

Other Contributors

Keratoconus has also been tied to eyelid laxity and sleep apnea.2-3 Side-sleeping with the eye pressed to the pillow may cause mechanical and thermal contributions to the eyelid and cornea. I’ve observed that patients with asymmetric keratoconus are more likely to develop a floppy eyelid on their sleeping side.

I’ve also seen a number of keratoconus patients with undiagnosed sleep apnea. I studied sleep apnea in keratoconus patients with Preeya K. Gupta, MD, a number of years ago, and we found that keratoconus patients have a higher prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea compared with the general population.4 There may be some association between a floppy cornea and floppy soft palate. We also found that patients who have corneal transplants for keratoconus have some inflammatory mediators such as MMP-9 at a higher rate in the cornea, just like people who undergo sleep apnea surgery. There may be more systemic floppiness going on.

We’ve also reported that patients undergoing keratoplasty for keratoconus have a higher likelihood of being morbidly obese.5 These patients weighed an average of 31.7 pounds more than age-matched controls (p=0.015). Based on BMI, patients with keratoconus were 1.6 times more likely to be classified as overweight, 2.2 times more likely to be classified as severely overweight and 9.1 times more likely to be classified as morbidly obese vs. controls. However, unlike other patients with sleep apnea, who tend to get a lot better when they lose weight, these keratoconus patients don’t usually see an improvement in sleep apnea with weight loss. They’re also more likely to have a floppy eyelid.

Deterring Eye Rubbing

Reducing the urge to rub the eyes may help to decelerate keratoconus progression. Patients with Intacs corneal ring segments report discomfort when they rub their eyes, and this serves as a deterrent. I found Intacs more predictable than crosslinking, in terms of improving keratoconus and contact lens wear. Many of my ring-segment patients years ago were able to avoid the need for a corneal transplant, while a few went on to DALK and successful contact lens wear. Counseling patients about the harmful effects of eye rubbing and other activities that cause mechanical trauma to the cornea may help to slow keratoconus progression in some patients.

Large-scale Genetic Testing

Identifying susceptible patients as early as possible would be wonderful. There’s a potentially large number of people with the genes for keratoconus—but this isn’t the full picture. Take the 23andMe test, for example. This test often tells people they have a risk of developing macular degeneration. There are genes that show you’re at risk for AMD, but many people also have genes that prevent or postpone its onset. The test doesn’t mention those.

I took the test, and it says I have a risk of developing macular degeneration. I probably got the genes from my 92-year-old father who only now shows early signs of macular degeneration. He probably has the genes for macular degeneration, but he probably also has the genes that postpone or prevent it.

So, for the most part,6 we don’t know what’s preventing us all from getting keratoconus, and we’re not testing for that. The commercial genetic test kits don’t work that way—they only look at genes associated with a particular disease.

Dr. Carlson is a professor of ophthalmology and a cornea specialist at the Duke University Eye Center in Durham. Contact him at alan.carlson@duke.edu.

1. Mazharian A, Panthier C, Courtin R, et al. Incorrect sleeping position and eye rubbing in patients with unilateral or highly asymmetric keratoconus: A case-control study. Graefs Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020;258:2431-39.

2. Ezra DG, Beaconsfield M, Sira M, et al. The associations of floppy eyelid syndrome: A case control study. Ophthalmol 2010;117:831-38.

3. Pihlblad M, Schaefer D. Eyelid laxity, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea in keratoconus. Cornea 2013;32:1232-36.

4. Gupta PK, Stinnett SS, Carlson AN. Prevalence of sleep apnea in patients with keratoconus. Cornea 2012;31:595-99.

5. Kristinsson JK, Carlson AN, Kim T. Keratoconus and obesity—A connection? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:e-abstract 812.

6. Yari D, Ehsanbakhsh Z, Validad H, et al. Association of TIMP-1 and COL4A4 gene polymorphisms with keratoconus in an Iranian population. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2020;15:3:299-307.

COUNTERPOINT: KERATOCONUS IS PRIMARILY A GENETIC DISEASE

Genetics Can’t Be Overlooked

There’s a strong genetic component to keratoconus, though other factors can be at play.

By Christopher J. Rapuano, MD

Philadelphia

The two-pronged hypothesis for keratoconus suggests that an eye-rubbing or a chronic eye trauma component is necessary in addition to a genetic predisposition in order for keratoconus to develop. I’m not convinced of that, however. Though there are definitely patients who rub their eyes and get keratoconus, whether they have a (known) predisposition or not, many patients progress in the absence of (known) eye rubbing. Even after corneal cross-linking, a small percentage of patients will progress. We suspect that some of these patients still rub their eyes or sleep with pressure on their eyes, but it’s possible that their keratoconus is so bad that crosslinking isn’t enough to stabilize it.

Family History

Genetics plays a key role in keratoconus development, alongside other environmental and mechanical factors. We know the condition occurs with higher frequency in certain ethnicities such as in Asian and Middle-Eastern people,1 and first-degree relatives of keratoconus patients have a much higher prevalence of keratoconus compared with the general population.2,3

Depending on how you define keratoconus, between 10 and 20 percent of these patients will have a family history of the condition. If a family member doesn’t have frank keratoconus, there’s a higher likelihood that their topography is somewhat abnormal, and this may bring the numbers up to 20 or 30 percent. So, just from family history, we know there’s a strong genetic component, though of course cases may be sporadic. I always ask my keratoconus patients about any family history of keratoconus. Frequently, they have a history, but certainly not always.

When patients see me for refractive surgery evaluations, I always ask if they have a family history of corneal problems, keratoconus or corneal transplants, because there have been cases in which patients with perfectly normal-looking eyes get refractive surgery such as LASIK and end up with ectasia. Then it turns out that they have a family history of keratoconus. We think patients with a family history of keratoconus may be predisposed to ectasia after refractive surgery. So, in these cases, we inform the patient about their possible increased risk of postoperative ectasia and may recommend no refractive surgery or may suggest PRK instead.

Seeking Candidate Genes

For decades, we’ve been trying to find a gene or set of genes for keratoconus. New tools for identifying genetic variations associated with keratoconus such as genome-wide association and linkage studies, as well as gene expression studies and RNA sequencing,4 have brought us closer to our goals, but the condition’s genetics are complex.

Yaron S. Rabinowitz, MD, has been researching keratoconus genetics for years. In 2016, his group reported that single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with the genes LOX, CAST, DOCK9, IL1RN, SLC4A11, HGF, RAB3-GAP1, TGFBI, ZNF469, ZEB1, VSX1, COL5A1, COL4A3, COL4A4, FNDC3B, FOXO1, MPDZ-NF1B, WNT10A, SOD1, IL1B, IL1A and microRNA MIR184 have been suggested to influence keratoconus, but not all the analyses of these genes completely confirm a role in pathogenesis.5

Dr. Rabinowitz’s group pointed out that keratoconus likely results from abnormalities in several biochemical pathways. For example, a 2020 genome-wide association study, which he was also involved in, reported that overexpression of the antisense RNA gene AP006621 may destabilize corneal structures.6 The researchers noted that this was related to a genome-wide significant locus for keratoconus that they identified in the PNPLA2 region on chromosome 11. This novel locus reached genome-wide significance in the four-cohort analysis (n=5,853; p=2.45x10-8).6 (The PNPLA2 gene, or patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 2 gene, is a protein-coding gene that encodes the enzyme that catalyzes the first step in triglyceride hydrolysis in adipose tissue.)7 Interestingly, the group also pointed out that the chromosome 11 locus overlaps with a previously reported but not genome-wide-significant association signal for Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy. Having both FECD and keratoconus together is rare, however. Having said that, we did report 27 cases.8

Some other variants that have been identified and linked to keratoconus risk include the rs1042183 variant in the ALDH3A1 gene in a Polish population, which was found to increase risk;9 the rs2228557 variant’s T allele in the COL4A4 gene, which was found to act as a protective factor vs. the C allele in an Iranian population;10 and the rs4898 variant in the TIMP-1 gene, where the TY genotype or T allele was found to decrease risk of keratoconus in Iranian males vs. the C allele, and was protective for the population.10

Associated Conditions

We also suspect that keratoconus patients may have some type of collagen abnormality, since floppy eyelid syndrome and sleep apnea are both seen fairly often among keratoconus patients. The COL5A1 gene, for example, is related to fibril-forming corneal collagen and to central corneal thickness, which has a strong genetic component. The keratoconus-associated loci RXRA-COL5A1, FOXO1 and FNDC3B have also been found to be associated with central corneal thickness.6

Atopic disease and Down syndrome are two other conditions associated with keratoconus, but they’re also both associated with eye-rubbing, so it’s unclear whether it’s the disease that’s genetically associated or whether these conditions, like allergies, cause eye rubbing, and the eye rubbing contributes to keratoconus.

Genetic screening to identify susceptible keratoconus patients early on has potential down the line. The AvaGen test from Avellino Labs (for which I’m a consultant) reliably tests for corneal dystrophies, such as lattice, granular and Reis-Bucklers dystrophies, but that’s because those dystrophies’ genetics are black-and-white: you either have the gene and therefore the dystrophy, or you don’t. AvaGen assigns a low-medium-high keratoconus risk score based on numerous mutations, but in the fairly small number of tests I’ve done recently, it’s unclear to me how helpful it was. As with any genetic test, as they get more subjects and more diverse populations, I’m sure the results will become more meaningful.

Further well-powered genetic research in large and diverse populations will help us learn more about keratoconus etiologies and guide new treatments.

Dr. Rapuano is a professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University and the Chief of the Wills Eye Cornea Service in Philadelphia.

1. Kok YO, Tan GF and Loon SC. Review: Keratoconus in Asia. Cornea 2012;31:581-93.

2. Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol 1998;42:297-319.

3. Lapeyre G, Fournie P, Vernet R, et al. Keratoconus prevalence in families: A French study. Cornea 2020;39:12:1473-9.

4. Bykhovskaya Y, Rabinowitz YS. Update on the genetics of keratoconus. Exp Eye Res 2021;202:108398.

5. Bykhovskaya Y, Margines B, Rabinowitz YS. Genetics in keratoconus: Where are we? Eye and Vision 2016;3:16:1-10.

6. McComish BJ, Sahebjada S, Bykhovskaya Y, et al. Association of genetic variation with keratoconus. JAMA Ophthalmol 2020;138:2:174-181.

7. PNPLA2 patatin like phospholipase domain containing 2 [Homo sapiens (human)] Full Report. National Library of Medicine. Updated August 5, 2022. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/57104.

8. Cremona FA, Ghosheh FR, Rapuano CJ, et al. Keratoconus associated with other corneal dystrophies. Cornea 2009;28:127-135.

9. Berdyński M, Krawczyk P, Safranow K, et al. Common ALDH3A1 gene variant associated with keratoconus risk in the Polish population. J Clin Med 2021;11:1:8.

10. Yari D, Ehsanbakhsh Z, Validad H, et al. Association of TIMP-1 and COL4A4 gene polymorphisms with keratoconus in an Iranian population. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2020;15:3:299-307.