In the past decade, we have gained deeper insight into the pathophysiology and treatment of dry eye. Both basic science research on dry eye as well as important expert workshops have elucidated our understanding that dry eye is a progressive inflammatory disease. This increased understanding has heightened the need for improved classification schemes, diagnostic approaches, and targeted therapies for the treatment of dry-eye disease and meibomian gland dysfunction. This article will summarize the current thinking in dry-eye disease, reinforce a stepwise approach in diagnosis and treatment, and establish treatment strategies based on risk factors and disease severity.

Definitions and Pathophysiology

In 2007, the International Dry Eye Workshop defined dry eye as "a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface."1

This definition emphasizes two central mechanisms in dry eye: hyperosmolarity of tears and inflammation of the ocular surface. This definition also emphasizes key features that define the nature and severity of the disease: tear film instability and ocular surface damage.

Dry-eye disease can be classified into two major subtypes: Sjögren's type or non-Sjögren's type aqueous tear film deficiency; and evaporative dry eye.

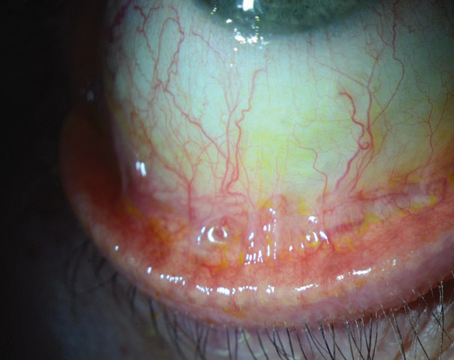

In patients with aqueous tear film deficiency, T-cell mediated inflammation plays a key role in the disruption of tear production and function. Patients with evaporative dry eye typically have lid disease, which leads to meibomian gland dysfunction, decreased production of lipid in tears and evaporation of tears. In most patients, the effects of dry eye of either subtype are symptoms of blurriness, stickiness, burning, stinging, foreign-body sensation, grittiness, dryness, photophobia and itching. Also, there are often accompanying signs of corneal and conjunctival inflammation. In more severe cases, the consequences of chronic dry-eye disease can include poor lubrication, altered barrier function, sterile melting, and bacterial keratitis (See Figures 1 and 2).

Tear production is regulated by neural communication between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands, also known as the integrated lacrimal functional unit. The integrated lacrimal functional unit consists of ocular surface afferent sensory nerves, efferent autonomic and motor nerves that stimulate tear secretion and blinking, and the tear-secreting glands (main and accessory lacrimal glands, conjunctival goblet cells and meibomian glands).

In dry-eye disease, this neural communication becomes disrupted, leading to tear hyperosmolarity and a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation. Tear hyperosmolarity causes damage to the surface epithelium by activating a cascade of inflammatory events at the ocular surface and a release of inflammatory mediators into the tears. Epithelial damage involves cell death by apoptosis, a loss of goblet cells, and disturbance of mucin expression, leading to tear film instability. This instability exacerbates ocular surface hyperosmolarity and completes the vicious cycle.

Because ocular surface and lacrimal gland inflammation has been found in dry eye and has been found to play a role in the pathogenesis of keratoconjunctivitis sicca, anti-inflammatory therapy can be used to effectively treat dry eye.

Disease Severity

In 2006, the International Task Force Delphi panel on dry eye developed treatment recommendations for dry-eye disease.2 The panel noted that disease severity is the most important factor to consider in treatment decision making. The group categorized disease severity into four levels based on symptom severity and frequency; visual symptoms; conjunctival injection; conjunctival staining; corneal staining; corneal/tear signs; lid/meibomian gland dysfunction; tear-film breakup; and Schirmer score.

The ITF developed profiles of signs and symptoms associated with each of the four severity levels. For example, patients with level 1 dry eye will have mild symptoms, mild conjunctival staining, a tear-film breakup time of less than 12 seconds, and a Schirmer score of more than 10 mm/five minutes. Patients with level 2 dry eye will have moderate symptoms, mild punctate corneal staining, visual signs in the tear film, a tear-film breakup time between two and seven seconds, and a Schirmer score between 5 and 10. Those with level 3 dry eye will have severe symptoms, marked conjunctival staining, marked punctate central corneal staining, filamentary keratitis, a tear-film breakup time of less than three seconds, and a Schirmer score of less than 5 mm/five minutes. Patients with level 4 dry eye will have severe symptoms, conjunctival scarring, severe punctate erosions seen during corneal staining, a tear-film breakup time of less than three seconds, and a Schirmer score of less than 2 mm/five minutes.

Recommendations for Treatment

These international experts also established treatment recommendations for dry eye based on the severity level. Each set of recommendations builds upon the previous level such that if improvement in signs and symptoms is not achieved, additional treatments are used.

For patients with level 1 dry eye, recommendations include education and modifications to the environment and diet, elimination of offending systemic medications, artificial tear substitutes, gels or ointments, and eye lid therapy.

If the level 1 treatments do not achieve the desired improvement, add the following level 2 treatments: anti-inflammatories, tetracyclines if patients have meibomianitis or rosacea, punctal plugs, secretogogues, and moisture chamber spectacles.

If these treatments do not achieve the desired improvement, add autologous serum, contact lenses, or permanent punctal occlusion (level 3 treatments). If the level 3 treatments are inadequate, add systemic anti-inflammatories and consider surgery.

Cyclosporine and Progression

To determine whether twice-daily treatment with topical cyclosporine 0.05% would slow or stop the progression of dry-eye disease, our group conducted a study that included 74 dry eye patients (Rao S. IOVS 2008;49: ARVO E-Abstract 100). Fifty-eight patients have completed one year of study. Of these 58 patients, 36 received twice-daily treatment with cyclosporine 0.05%, while 22 patients received twice-daily treatment with artificial tears. Patients were seen at baseline and at months four, eight and 12.

Two thirds of patients in both groups were categorized as having level 2 dry eye at baseline, and the remaining one third were categorized as level 3. While 31.8 percent of patients who received artificial tears experienced progression of disease, significantly fewer (5.5 percent) patients in the cyclosporine 0.05% group experienced progression. Additionally, patients treated with cyclosporine had a mean improvement in Schirmer scores of 24.1 percent, compared with a mean decrease of 2.4 percent in patients who received artificial tears. Patients treated with cyclosporine also had a 33.7 percent improvement in tear breakup time, while those treated with artificial tears had a 7.4 percent worsening in tear breakup time. Cyclosporine was also found to provide a significant increase in goblet cells (24.8 percent improvement) compared with a 3.2 percent decrease in patients who received artificial tears.

Assessing Risk of Progression

Our study suggested that the natural history of moderate to severe dry-eye syndrome is progressive in a significant percentage of patients. Because we do not have a single test to determine the risk of progression, we use risk factor profiling to identify patients at highest risk of progression. Substantiated risk factors for dry eye include: female gender; older age; postmenopausal estrogen therapy; a diet low in omega 3 essential fatty acids or a diet with a high ratio of omega 6 to omega 3 fatty acids; LASIK and refractive excimer laser surgery; vitamin A deficiency; medications such as antihistamines; connective tissue disease; radiation therapy; and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In patients with multiple risk factors for dry eye, we aggressively use anti-inflammatory treatment.

New Treatment Paradigm

The traditional treatment paradigm for dry eye involved treating patients based on a stepwise approach. This often meant starting all patients on artificial tears until symptoms or clinical signs warranted a change in therapy. Given our understanding that dry eye is a progressive disease, this traditional approach of starting all dry-eye patients on artificial tears may be sub-optimal and may allow progression of disease.

In contrast, the new treatment paradigm takes into account emerging evidence that dry-eye syndrome is a progressive disease. Therefore, ophthalmologists should identify those at risk of progression and treat patients at highest risk with more targeted therapy, including cyclosporine 0.05%. In addition, moderate dry eye is much more responsive to treatment than severe dry eye. Once patients progress to severe dry eye, even cyclosporine may not work well.

A recently published study found that, while topical cyclosporine is beneficial for all levels of dry eye, symptomatic improvement was greatest in the patients with mild dry eye.3 This prospective clinical study included 158 consecutive patients with dry-eye disease that was unresponsive to therapy with artificial tears. Patients were divided into three groups based on severity. Sixty-two patients had mild dry eye, 69 had moderate disease and 27 had severe disease. Researchers used the Ocular Surface Disease Index to evaluate patients with regard to symptomatic improvement, tear break-up time, fluorescein staining, lissamine green staining and Schirmer testing. Patients were observed for three to 16 months. According to the study results, 74 percent of patients with mild dry eye, 72 percent of patients with moderate dry eye and 67 percent of patients with severe dry eye showed improvement. This translates to an overall improvement rate of 72 percent.

In our practice, our treatment approach takes into account patients' dry-eye severity level as well as their risk factors for progression. For example, a patient with level 1 dry eye and no risk factors can be started on artificial tears, while a patient with level 1 disease and multiple risk factors will also receive a discussion of risk factor modification. A patient with level 2 dry eye and no risk factors may receive artificial tears, a short course of anti-inflammatories or punctal plugs, while a level 2 patient with multiple risk factors should receive cyclosporine A 0.05%, an anti-inflammatory, and risk factor modification. For level 3 and 4 patients, targeted therapy and risk factor modification must be employed early.

Our understanding of dry eye has advanced remarkably in the past decade. Not only is dry eye now considered a chronic inflammatory disease, but also a potentially progressive disease, much like glaucoma. Ophthalmologists can use risk factors and disease severity levels to identify high-risk patients, and patients at highest risk of progression should be aggressively treated with targeted therapies like cyclosporine A.

Dr. Rao is the medical director of Lakeside Eye Clinic in

1. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5:75-92.

2. Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, et al; Dysfunctional tear syndrome study group. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: A

3. Perry HD, Solomon R, Donnenfeld ED, et al. Evaluation of topical cyclosporine for the treatment of dry eye disease. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1046-1050.