Recent data continues to support the idea that SLT is a reasonably safe and effective first-line treatment option in open-angle glaucoma and high-risk ocular hypertension. The SLT vs. medication study,1 a prospective, randomized clinical trial for which our clinic was the coordinating center, offered laser as a first-line option and compared outcomes with patients receiving one-drop therapy with a prostaglandin. Twenty-nine patients received SLT; 25 received medical therapy in both eyes. After nine to 12 months follow-up, intraocular pressure had fallen from 24.5 mmHg to 18.2 mmHg in the SLT group and from 24.7 mmHg to 17.7 mmHg in the medication group (not a statistically significant difference). Also, by final follow-up, 11 percent of SLT eyes had received additional SLT, while 27 per-cent of eyes in the medication group required additional medications.

Given its increasing popularity, I’d like to discuss some of the latest developments relating to SLT and share some thoughts regarding issues that are frequently raised during discussions about the laser.

Getting Closer to an Explanation

One SLT-related development of note in recent years has been progress in our understanding of how laser trabeculoplasty acts to reduce IOP. Jorge Alvarado, MD, in San Francisco, deserves a lot of credit for the work he’s done investigating the way lasers affect the tissues in the angle. He’s demonstrated that a whole cascade of events takes place; the laser triggers biochemical changes that lead to the production of cytokines, and macrophages are recruited to the lasered area. Among other things, this causes the intercellular junctions to loosen, allowing aqueous to get to Schlemm’s canal more easily. Mark Latina, MD, the inventor of the laser, calls this a “rejuvenation” of the angle.

There’s still a controversy regarding whether SLT and prostaglandins share a common pathway for lowering pressure. Some people believe they do, saying that if you’ve done laser effectively and completely, prostaglandins shouldn’t have any additional pressure-lowering effect. Others argue that there is still some additive effect between the two options.

So far, this hasn’t been conclusively resolved. However, my experience suggests that there is, in fact, an additive effect. If I have a patient on

a prostaglandin and he’s not adequately controlled, I’ve seen an additional benefit from doing laser trabeculoplasty. The gain is not as profound as if the patient were on a beta blocker rather than a prostaglandin analog, but there is often a gain. Some would argue that this occurred because the patient wasn’t being compliant with the prostaglandin, or the SLT treatment wasn’t complete. But in my experience, the additivity can’t solely be explained by those caveats.

|

Practical Concerns

In terms of using laser trabeculoplasty in the clinic, several issues occasionally arise:

• When is SLT contraindicated? In certain situations, SLT is unlikely to be effective. If the patient has a secondary glaucoma such as neovascular glaucoma, traumatic angle recession or inflammatory glaucoma, SLT probably won’t work well. Also, if a patient has severe damage and a very high pressure such as 50 mmHg and you want to get the pressure down quickly, laser may not be the best choice; in that case, medications and/or surgery would be indicated. And, of course, SLT is contraindicated if you can’t see the angle structures due to factors such as corneal haze.

On the other hand, SLT can be effective when you’re dealing with primary open-angle glaucoma, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma or pigmentary glaucoma.

• Are SLT and corticosteroids compatible? When considering whether it’s advisable to treat a patient with both SLT and steroids, there are two possible scenarios to consider. The first is when steroid use has resulted in open-angle glaucoma: Is it advisable to treat that type of glaucoma with SLT? These patients may have been placed on topical steroids or intraocular steroids to address macular edema, or placed on oral steroids for some type of systemic or skin condition. According to a couple of small studies, laser trabeculoplasty does work pretty well at lowering pressure in these individuals.

The second scenario to consider is whether it makes sense to use anti-inflammatory drops such as steroids for a period of a few days or a week following laser treatment. This type of protocol was traditional after argon laser trabeculoplasty, which we started doing in the 1980s. We know that lasers cause a little bit of inflammation, so steroids were routinely used to suppress inflammation for about a week after the treatment.

Today, researchers like Jorge Alvarado, MD, have suggested that the inflammation produced by SLT is pretty mild and self-limiting. More important, the small amount of inflammation caused by the laser may play an important part in setting in motion the cellular bio-chemical processes in the angle that improve aqueous outflow, allowing the pressure to drop.

For this reason, many ophthalmologists have stopped using steroids after SLT; they either use no drops postlaser or may use a topical nonsteroidal for a few days.

• Can SLT be combined with cataract surgery? Using SLT in conjunction with cataract surgery is a less-exciting alternative for lowering pressure these days, in part because we now know that the cataract surgery itself will lower the pressure in certain patients, and in part because of the minimally invasive glaucoma surgery options, or MIGS, that are now available. However, SLT may be effectively used after cataract surgery—almost as well as if the patient was still phakic. (That wasn’t the case in the old days when cataract surgery required making a large incision.) So if you perform cataract surgery and the pressure doesn’t come down quite as much as you’d hoped, SLT is a reasonable next step.

The Patient Attitude Factor

Patient attitudes toward firing a laser into the eye are a significant factor in how often laser trabeculoplasty is chosen. Depending on the patient’s level of understanding, the reaction may be positive or negative. Individuals who are well-informed about SLT—often because they’ve investigated the procedure on their own—are usually excited about doing the laser. They know it’s relatively safe and painless, and they’re usually aware of the side-effect issues and daily regimen associated with medications.

|

Unfortunately, this means that in many cases there has to be a fair amount of educating by the physician. Some doctors do take the time to educate uninformed patients about the procedure, but a lot of doctors, with their time and energy already stretched to the limit, don’t want to be burdened with this. So when they sense the reluctance of a patient regarding the laser, they often just choose to exhaust the medication options before resorting to it.

Another patient-attitude issue that affects the use of SLT is that the public has been taught in some ways to question the medical system. Some people aren’t convinced that doctors know what they’re doing, or are concerned that a doctor may be pushing an option for his or her personal gain. They may think the surgeon wants to use the laser because he can make more money by doing so than by prescribing medications. Doctors don’t like being put in the position of seeming like a salesman, so in some situations that may influence them to opt for prescribing medications, simply to avoid the appearance that the choice was self-serving—especially since laser trabeculoplasty does not subjectively improve a patient’s vision.

For all these reasons (and possibly others) there may be a reluctance on the part of doctors to push SLT too far to the forefront of treatment options. Exhausting reasonable medication options before resorting to the laser is simply more acceptable to many patients who don’t know much about laser trabeculoplasty.

Given the problems associated with medication use, this is ironic. Doctors understand the issue, however; if you ask a group of doctors whether they’d start with laser or medications to treat their own glaucoma, quite a few will choose the laser.

Patient Adherence

Medications may work well for managing glaucoma—and they may appear to be working well when patients come in to see us because the patients have used the medication before the visit—but if patients are not using their medications every day, we’re not going to achieve our goal of preserving vision.

Certainly one of the great advantages of laser trabeculoplasty is that it eliminates problems with patient adherence. Even in the old days doctors knew that questionable patient adherence was a problem, but we tended to hope for the best. These days I think it’s clear that we can’t continue with that attitude, because people are still losing vision on our watch. One reason is lack of compliance using medications.

Of course, other alternatives can also help to address this issue, including using trabeculectomy as primary treatment, or implanting a shunt. Another exciting area that hasn’t fully blossomed yet is alternative drug delivery; we may be able to use contact lenses, punctal plugs or intraocular injection to deliver medications, eliminating the patient compliance issue. I think there’s every intention on the part of physicians to find ways to keep pressure lowered without depending on eye drops. At the moment, however, one of the best and least-risky options for doing that is laser trabeculoplasty.

Helping the Community

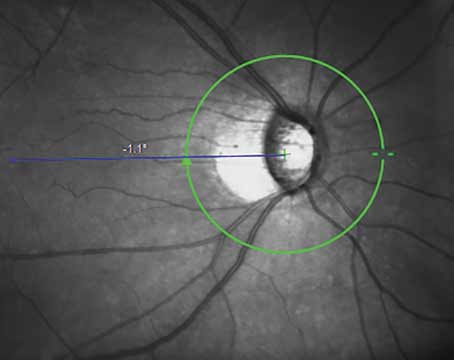

Because SLT avoids the issue of patient compliance, it’s a particularly good option for treating individuals in communities that are underserved and unlikely to support the continuous use of medications. In that spirit, our clinic is currently involved in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention public health program, a pilot screening initiative in Philadelphia. We’re reaching out to high-risk underserved populations with mobile units. We send a team of medical personnel with all of the equipment necessary to do a complete eye exam, including visual fields, slit-lamp exam and optic nerve photography, and engage individuals in a multi-step process.

The first step is an educational component in which participants go to a senior center in an African-American neighborhood. Everybody attends a lecture on glaucoma explaining what it is and how it’s treated. We talk about laser as well as medication; it’s not a long program and it’s very basic. After that, we’ve had virtually 100 percent follow-up in terms of people wanting to attend the glaucoma screening. After the screening, patients identified as having glaucoma are offered the option of receiving laser or medical therapy right on the spot, and many choose laser as the first therapy. That supports the idea that a patient’s decision about the laser may hinge on understanding what laser therapy is, how it works, and the risk profile associated with laser and medications.

The value of this kind of effort has been well-demonstrated in the St. Lucia study, recently published by Tony Realini, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at West Virginia University Eye Institute in Morgantown, W.Va.2 In this study, 61 individuals of African descent in St. Lucia who were being medically treated for primary open-angle glaucoma underwent a 30-day wash-out followed by bilateral 360-degree SLT. All eyes showed a sustained response to the therapy even at one-year follow-up; 78 percent had at least a 10-percent reduction in pressure from the post-washout level; and 93 percent of successful subjects had IOP levels lower than the levels they’d achieved with medication. This certainly supports the idea that SLT can be a big help in communities that don’t necessarily have the means to support chronic medical therapy.

SLT won’t be effective for everybody, and it’s not going to work forever (although it may be repeatable). But if you treat people in the community who are high-risk—especially if they’re relatively young—you’re at least starting them off on a good footing. That one step could be very helpful for the population as a whole.

From the perspective of a public health official, I would see this as being akin to using fluoride in drinking water. On a smaller scale, that’s what we’re trying to do with the CDC project in Philadelphia. But whether you’re helping underserved individuals in the community or managing patients in your clinic, a treatment that’s effective and avoids the problem associated with patient adherence is a powerful tool to have in your armamentarium. REVIEW

Dr. Katz is the director of the Glaucoma Service at the Wills Eye Institute in Philadelphia. He has received past research grants from Lumenis.

1. Katz LJ, Steinmann WC, Kabir A, Molineaux J, Wizov SS, Marcellino G; SLT/Med Study Group. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus medical therapy as initial treatment of glaucoma: a prospective, randomized trial. J Glaucoma 2012;21:7:460-8.

2. Realini T. Selective laser trabeculoplasty for the management of open-angle glaucoma in St. Lucia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:3:321-7.