Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy goes by a few different names, but its “egg yolk” presentation remains a consistent finding in affected eyes. Depending on the disease stage, most patients have few symptoms and only mild visual impairment. However, AOFMVD is a progressive disease with no treatment, and in the atrophic stages, central vision loss is common. Because of relatively mild vision symptoms during most stages and its resemblance to age-related macular degeneration, this condition is often misdiagnosed. Here, retinal specialists discuss how to identify AOFMVD and differentiate it from macular degeneration.

Consequences of a Misdiagnosis

Vitelliform dystrophy may have phenotypic presentations similar to AMD but it has different underlying genotypes. “The term ‘adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy’ is a completely descriptive term and it’s a clinical diagnosis,” explains Ian C. Han, MD, an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at University of Iowa Health Care, Carver College of Medicine. “There are differences between the traditional clinical diagnosis and this era of advanced imaging and molecular genetic diagnoses. If you’re in a high-volume clinical practice and see a lot of macular degeneration, it’s likely that quite a few patients have something that’s more vitelliform, if you will, but is simply being labeled as AMD because the patient’s vision is pretty decent—and they’re older, so it’s fine to call it AMD. What’s most clinically relevant right now is that if something looks a bit off from typical AMD, you can consider it an AMD masquerader.”

It’s important to catch a misdiagnosis as soon as possible, experts say. In addition to causing undue worry and distress about losing vision, a misdiagnosis of AMD may mean that the patient has been undergoing unnecessary injections, says Jay Chhablani, MD, a vitreoretinal specialist and an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh Eye Center. “It’s essential to rule out this disease and understand that injections won’t benefit the patient at all, unless there’s CNV involved,” he says.

Injections come with a financial burden and certain risks. “Every time you do an injection, not only do patients experience discomfort during and after, but there’s also the psychological toll of getting these injections and the risk of endophthalmitis,” says Jason Hsu, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University and faculty member of the Retina Service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. “There’s limited data on using anti-VEGF for AOFMVD, and nothing so far indicates it has any effect—good or bad—on the disease. Additionally, many patients have been started on AREDS vitamins for macular degeneration, which can be quite expensive.”

Shared Mechanisms, Mysteries

AMD and its mimickers, such as AOFMVD, Best’s disease and other pattern dystrophies, share a malfunction at the level of the RPE and choroid. “Vitelliform lesions of AOFMVD have high levels of lipofuscin,” notes Dr. Hsu. “It’s believed to be the result of accumulation of photoreceptor outer segments that failed to be digested by the underlying RPE cells, leading to buildup in the subretinal space. However, the reason for this malfunction isn’t wholly understood yet.”

Disease Stages

Disease stages correspond to the breaking up of the lesion, from the vitelliform stage to the pseudohypopyon stage and on to the vitelliruptive and atrophic stages. “We aren’t currently aware of the mechanism behind the breaking up of the lesion, but we do know that there’s an established genetic association,” Dr. Chhablani says. “The staging is similar to what we sometimes see in Best’s disease.”

Dr. Hsu explains that any of these stages may be misdiagnosed as AMD, especially the vitelliruptive (“scrambled egg” stage) and pseudohypopyon stages, which may be taken as wet AMD with fluid; or the earlier vitelliform stage which may look like dry AMD. The atrophic stage may masquerade as advanced dry AMD with geographic atrophy. “The area of atrophy tends to be very circular in the center of both eyes, rather than a more irregular shape that you’ll sometimes see with typical geographic atrophy from AMD,” he notes.

Vitelliform stage. “In my practice, the most common stage at which patients present is usually the vitelliform stage, which has an egg-yolk-like lesion under the fovea,” Dr. Hsu continues.

Pseudohypopyon stage. “The next stage sort of mirrors what we hear about with Best’s disease,” he says. “In my experience, it’s been rare to see an adult-onset foveomacular dystrophy having a pseudohypopyon stage, in which there’s a layering of heavier proteinaceous material inferiorly, due to gravity. The superior portion of the lesion looks more clear and fluid-filled.

“When you do an OCT scan through this pseudohypopyon, you’ll see the appearance of the sedimented deposit has a hyperreflective signal on OCT, whereas the superior portion with fluid will look dark, or hyporeflective,” he says. “I’d say this pseudohypopyon stage is when even retinal specialists may think there’s an underlying CNV membrane and start doing injections. That’s one thing to look out for.”

Vitelliruptive stage. “As the disease progresses, we come to the vitelliruptive stage, which resembles scrambled eggs,” Dr. Hsu says. “It no longer has a uniform grey/yellow appearance. Now there’s some atrophy developing due to resorption of this vitelliform material. Essentially, it shrinks down.”

Atrophic stage. “In the atrophic stage, the material is completely resolved but there’s still loss of the RPE and some of the outer retina,” he says.

Paradoxically, as the lipofuscin resorbs, vision usually worsens. The resorption mechanism in the atrophic stage is unknown, but one theory suggests it may be due to photoreceptor death and the subsequent decrease in production of the outer segments. “With fewer outer segments to eliminate, the RPE may catch up and eliminate the waste,” Dr. Hsu says. “I’ve had patients who haven’t lost vision or even showed improvement, so some patients do continue to see well after the material resorbs. Most, however, experience worsening of vision.”

Lesions

Both AMD and vitelliform dystrophies, whether juvenile- or adult-onset, have yellowish deposits. Clinically, the main difference between the AMD and adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy is the color and distribution of these deposits, explains Dr. Han.

“When you look on imaging and histology for traditional AMD, the deposits aren’t just subretinal but predominantly sub-RPE,” Dr. Han says. “They’re more discrete and round: classic drusen. They may or may not be located subfoveally and can also be distributed throughout the macula. Some have softer borders and can be confluent, but are typically discrete.

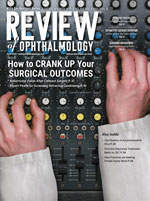

|

“Clinically, vitelliform deposits can look similar to AMD early on,” he continues. “However, when you see a vitelliform deposit that’s classically subfoveal, larger, isolated, rounder and more yellow than your typical drusen or soft drusen, that’s when a clinician may start to think of AOFMVD. Drusen tend to be a bit clumpy, but the vitelliform lesion, as the name suggests, looks more like an egg yolk with a characteristic yellow color.”

“Unlike the sister diagnosis of Best’s disease, whose lesions are very large in the central macula, AOFMVD lesions tend to be about 500 microns in diameter and are usually very round or oval in shape,” adds Dr. Hsu. “Often, they’ll have a pigmented spot in the center as well.

“There’s also something called subretinal drusenoid deposits that have been described with AMD as well, so not all AMD drusen is sub-RPE,” he cautions. “However, vitelliform dystrophy will have much more prominent and a greater accumulation of subretinal hyperreflective material.”

Differential Diagnosis

There’s a reason this disease is often mistaken for AMD, Dr. Hsu says. “For one, it’s not terribly common, and for another, many of these patients have only central lesions in their macula, while others will have associated drusen around the lesions, or RPE changes,” he says. “Some dystrophies are clear-cut, but the spectrum of this disease may be very similar to the spectrum of macular degeneration.”

Dr. Hsu says it’s easiest to diagnose patients when they come in with their disease in the vitelliform stages, when it resembles a single egg yolk in each eye. “Sometimes I’ll see some surrounding drusen, but usually the drusen are much less prominent and this one lesion is very prominent. That’s my usual clue that this is more of a vitelliform than an AMD eye. It becomes more difficult to differentiate as it advances.”

“I think the most important thing to keep in mind when differentiating AOFMVD from AMD is that AOFMVD is primarily a bilateral, symmetrical disease, and unassociated with surrounding atrophy and AMD-associated signs which you’ll see in the acquired vitelliform lesions associated with AMD,” says Dr. Chhablani. “If patients present to you with bilateral, symmetrical deposits in the center with no drusen around them, then you should be thinking: Probably not AMD.”

Though it typically presents bilaterally and symmetrically, this isn’t always the case, notes Dr. Hsu. “I’ve seen it present very asymmetrically, where one eye will have a very prominent lesion and the other eye will have a much smaller, less noticeable lesion that I’d have almost glossed over if I hadn’t seen the lesion in the other eye,” he says.

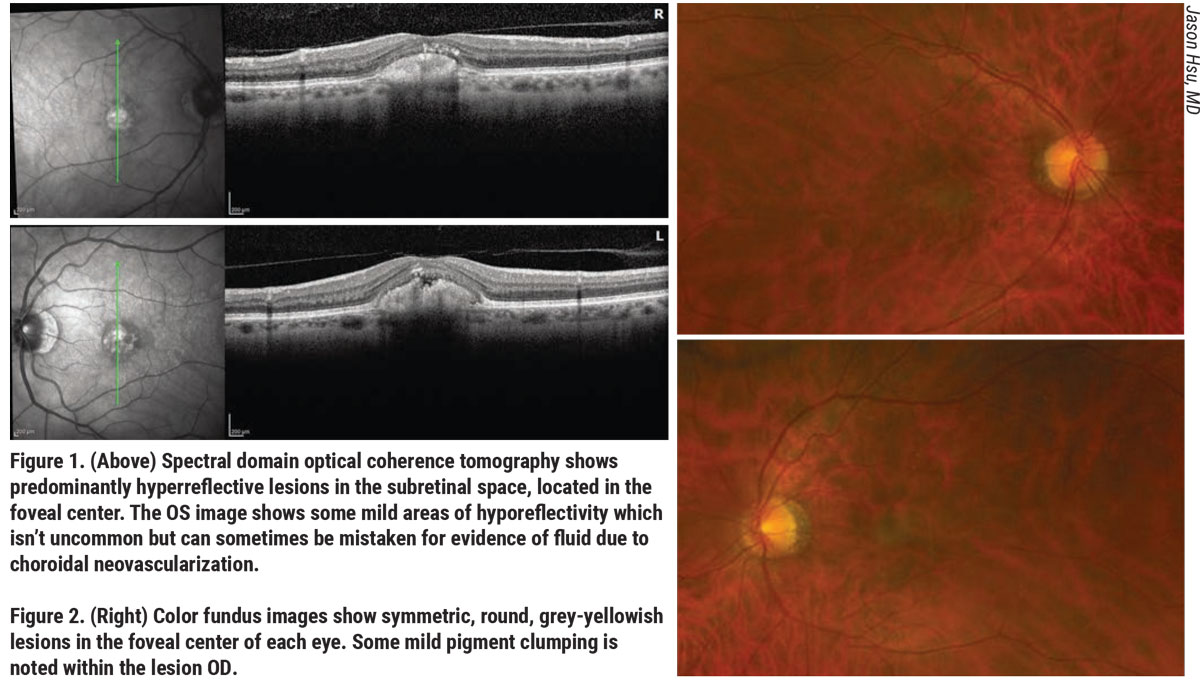

“Age of onset is another important question for any potentially genetic vision condition,” says Dr. Han. “Typical AMD is defined as occurring at greater than age 50. Most patients come in in their 60s, 70s or 80s. If you have someone with ‘adult-onset’ FMVD, they might be 30 or 40 years old with their earliest symptoms starting then. If you notice earlier onset, ask about family history. That yellow egg-yolk-like deposit that doesn’t look like typical drusen is a trigger to think about for referral and when you look at structural OCT. The location of these deposits are important clues: They’re typically subfoveal and subretinal.”

With many patients referred for macular degeneration, what leads a clinician to suspect that there’s been an incorrect diagnosis? “This falls under the category of differentials for non-responders,” Dr. Chhablani says. “If you’re seeing that your patient has subretinal fluid or hyporeflective space on OCT that’s not flattening, and you’re considering this to be subretinal fluid and possible CNV, that’s the time to go back and look at your imaging, such as autofluorescence, or do a detailed examination of past OCTs. If you did fluorescein angiography, then check those again. OCTA also allows us to rule out the vascular network, which you see in wet AMD but not in AOFMVD.”

Imaging Modalities

Experts agree that OCT is probably the most useful imaging modality for detecting AOFMVD. When AMD and AOFMVD deposits look similar on clinical examination, OCT can help you make the final call by checking where the material is accumulating. “If you look carefully at cross-sectional imaging, the vitelliform deposits tend to be truly subretinal, in the sense that they’re between the neurosensory retina and above the level of the RPE,” Dr. Han says. “It’s accumulating above the level of a brighter band on OCT of the RPE and can sometimes be seen associated with elongation of the photoreceptors, along with some hyporeflective space. We tend to use the term neurosensory detachment because it’s probably some light thinning of the photoreceptors where the retina’s actually separating from the RPE.”

“If vision is good and your OCT shows a nice, uniform, hyperreflective lesion that’s clearly in the subretinal space, you’ll see preservation in areas such as the outer retina, ellipsoid zone and external limiting membrane,” adds Dr. Hsu. “That’s the easiest time to diagnose this condition.”

Dr. Chhablani’s advice is to look carefully. “If you do an OCT and see hyporeflective space, don’t assume it’s subretinal fluid,” he points out. “When we see hyporeflective areas and think subretinal fluid, we think of anti-VEGF injections, but in the case of AOFMVD we don’t want to do that. When I’ve had patients who’ve been injected before, I ask them to bring their previous OCTs. It’s important to examine their previous OCTs and see their treatment history and treatment response. If their response wasn’t good, start thinking that this might not be AMD but AOFMVD. Start investigating. Seeing hyporeflective space and initiating injections in a very conventional way isn’t a great idea.

“If you suspect choroidal neovascularization, look carefully at the whole volume OCT scan,” he continues. “Scroll up and down again and again. Be sure to look for a type-1 component, and look for RPE breach if you suspect type-2 CNV membrane. If you can’t make out anything, observing the patient for two more weeks won’t hurt, or you can inject and see if there’s no response. Hold off on the second injection and see if it worsens. If there’s a very subtle, slow leakage, you can wait for a week and see how the disease worsens.”

While fluorescein angiography is helpful for identifying CNV in AMD, it’s not particularly useful for visualizing a potential CNV net in vitelliform conditions, including Best’s disease. This is because the dye leaks into the lesions, making it difficult to tell whether there’s abnormal CNV leakage or the usual leakage associated with vitelliform lesions. Dr. Hsu explains, “The lipofuscin blocks the underlying fluorescein dye. Then, there’s often a rim of hyperfluorescence surrounding that lesion due to some RPE changes. If you do FA in an atrophic stage, it’ll just be a window defect in the center.”

Dr. Han says that OCTA is more helpful for visualizing a CNV net in vitelliform diseases, even though it doesn’t show leakage. “OCTA is basically motion-capture of blood cells going through blood vessels,” he explains, “but for vitelliform diseases, it’s advantageous because the leakage obscures everything when you look on FA. With OCTA, you can actually see through the vitelliform lesion to a potential CNV membrane under the retina.”

For cases of AOFMVD without CNV, Dr. Chhablani says you’ll see a shadow artifact on OCTA from the vitelliform deposit. “If you were suspecting subretinal fluid due to CNV, and OCTA turns up no vascular network, then that rules out the diagnosis of wet AMD, which is helpful.”

A clinical exam and OCT are usually all you need to diagnose AOFVMD, but if you’re still unsure, experts say fundus autofluorescence is a good ancillary test. “Typically you’ll see a hyperautofluorescent lesion corresponding to the yellow spot we see in both eyes,” says Dr. Hsu. “The pattern of the autofluorescence is key. If you perform autofluorescence on an AMD eye, you’ll often see patchy areas of hyperautofluorescence where some drusen are located and other areas where there’s pigment clumping, which will appear as hypoautofluorescence. AMD has a very heterogeneous pattern, whereas vitelliform dystrophy is mostly homogeneous. You’ll see a bright, central spot where the lesions are located and everything around it will look fairly normal and intact.

Genetic Etiology

Further genetic studies may reveal more about the etiologies of these diseases. “AMD has a trend toward genetic characterization, and many of its masqueraders such as AOFVMD likely have a genetic cause or the patient has a genetic predisposition,” Dr. Han says. “Symmetry between the two eyes is usually a clue to macular dystrophies that have a genetic predisposition, as opposed to AMD, which usually has bilateral involvement but is asymmetric. There’s probably a broad spectrum of age-related accumulation of debris in the retina with a genetic background.”

AOFMVD hasn’t been attributed solely to a genetic etiology, but there are several genes potentially implicated in the condition, including BEST1 and interphotoreceptor matrix proteoglycan or pattern dystrophy genes such as IMPG1, IMPG2 and RDS, also known as PRPH2. Best’s disease, or juvenile-onset FMVD, is linked to the BEST1 gene but doesn’t always show up in childhood, despite its name. It’s often clinically diagnosed as adult-onset FMVD, in the absence of genetic testing.

|

“One of the classic genetic features of autosomal-dominant diseases is what we call incomplete penetrance, which means that not everyone will express the full strength of the mutation,” says Dr. Han, explaining these late manifestations. “Variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance may manifest in a wide spectrum across family members. Some patients fit cleanly into one box of clinical diagnosis and others don’t. We tend to label patients as having Best’s disease of late onset when they have a BEST1 mutation. Because of variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance, we’re not surprised if someone with a BEST1 genetic variant has a later onset of disease, even though it’s clinically diagnosed as a juvenile macular dystrophy. It’s helpful to examine other family members, even if they’re allegedly asymptomatic.”

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is more often reserved for severe or systemic disease or diseases with wide-ranging implications that may affect multiple generations. Most clinicians don’t offer genetic testing for AMD or AOFMVD because the results won’t change much about disease management, even when distinguishing between the two.

Dr. Chhablani says you can rule out Best’s disease without resorting to genetic testing by doing an electrooculogram. “Best’s disease will have a subnormal or reduced Arden ratio,” he says. “If I don’t see any changes on EOG, then I don’t usually ask for a genetic test.”

Dr. Han says he offers genetic testing for patients with AOFVMD. At the Carver College of Medicine, he has easy access to the Carver Non-Profit Genetic Testing Laboratory, which has one of the largest collections of genetic testing for eyes in the world.

“In your daily clinics of AMD patients, it’s highly likely that some have a genetic predisposition to macular disease that may currently or in the future be determined to be something other than AMD,” Dr. Han says. “Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy is a clinical diagnosis. The terms ‘adult onset’ and ‘vitelliform’ are very instructive. We’re moving into the era of genetics and advanced imaging, so we’re seeing that some of these AOFMVD patients turn out to have late-onset Best’s disease. Others probably just have some level of anatomical dysfunction in the photoreceptor-RPE-choriocapillaris unit that’s shared with the pathophysiologic mechanisms of multiple diseases. Depending on how that abnormal clearance of debris manifests, it can look similar on clinical examination but may have a different underlying genetic basis.”

Dr. Hsu, Dr. Han and Dr. Chhablani have no relevant financial disclosures.