Get Ready for a New Day

Think of the tremendous benefits sustained-release therapy can provide now and in the future.

By Andrew Camp, MD, San Diego

Are you wondering why you should use the new sustained-release bimatoprost implant for your glaucoma patients when you’re permitted to use it only once, lowering intraocular pressure for no more than six months in many cases? When considering bimatoprost SR (Durysta), perhaps you wonder how beneficial it will be for patients on multiple topical medications? After the bimatoprost implant biodegrades and you need to replace it by returning to a bimatoprost drop, will it seem like taking a step backward after taking a step forward?

I know these questions have been on the minds of many of my colleagues since last March, when this formulation was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the reduction of IOP in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. In response to these questions, I suggest we look beyond the current limitations of bimatoprost SR and explore the long-range benefits of what is truly a tremendous breakthrough therapy: the first implantable, sustained-release treatment for our glaucoma patients. Here, I’ll outline three major factors that support the use of sustained-release glaucoma medications—improving compliance, increasing efficiency of treatment and introducing a pathway for new medications—and I’ll explain why sustained-release therapy will soon become as common as traditional medications.

Bimatopost SR Performance

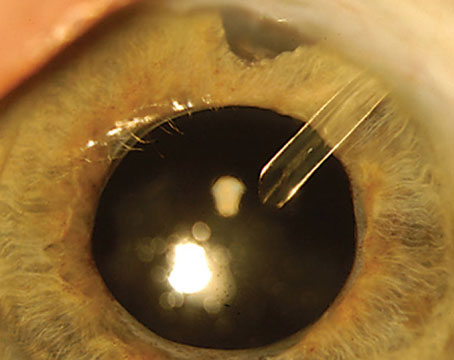

Bimatoprost SR, administered by intracameral injection, is composed of biodegradable polymers that gradually release bimatoprost over 90 days. I participated as an investigator in ARTEMIS I, one of two 20-month randomized, controlled Phase III clinical trials that involved 1,122 patients.1 In the trial, patients were randomized in the study eye to a 10-µg implant (which was later FDA-approved) or a 15-µg implant; or to topical timolol maleate 0.5% delivered twice daily to the topically-treated eye. Patients randomized to the implant received one of the two different-size implants three times over a 32-week period.

After 12 weeks, the IOP-lowering effects of both implants were noninferior to timolol, post-administration. Mean diurnal IOP was 24, 24.2, and 23.9 mmHg at baseline and from 16.5 to 17.2, 16.5 to 17.0, and 17.1 to 17.5 mmHg through week 12 in the 10-µg implant, 15-µg implant, and timolol groups, respectively.2 Meanwhile, an earlier, Phase I/II APOLLO trial involving 75 patients who received 6-, 10-, 15- or 20-µg bimatoprost SR implants, compared to bimatoprost drops, produced similarly beneficial results.3

Even though bimatoprost SR was approved for one-time use, most of us involved in the FDA trials hope increased use of the implant and additional studies will lead to expanded approvals. Corneal endothelial cell loss and treatment-associated inflammation, most prevalent after 15-µg injections, appear to have motivated the FDA to stick to its limited approval for the time being. Ongoing Phase IV trials should shed more light on the efficacy and safety profile of the 10-µg implant.

We see potential for the implant to be effective for far longer than the initially planned 90-day drug elution window. For example, 30 percent of eyes treated once with bimatoprost SR 10-µg and 15- implants in the APOLLO Study didn’t need to be rescued or treated for 24 months after one injection.

The IOP readings of bimatoprost SR and topical bimatoprost subgroups in this study were nearly matched in the 14-to-16-mmHg range and didn’t start to separate significantly until month 24.

Improved Compliance

|

Why is the introduction of sustained-release medical treatment of glaucoma groundbreaking? Consider that one of the greatest barriers to topical medication use is the poor compliance of patients with topical therapy.4,5 We know that the more patients need to use drops each day—both the number of times they need to put a drop in their eyes and the number of bottles they need to use—the more their compliance decreases. Implantable medication removes this barrier of non-compliance. In the retinal care arena, we’ve already seen improved outcomes in patients with the use of longer-acting anti-VEGF treatments or sustained steroid release agents, instead of monthly injections.6 Hopefully, by increasing the length of time a medication is available through a sustained-release device for glaucoma patients, we’ll achieve similar success.

Sustained-release medications will greatly benefit our patients, many of whom are on multiple medications. Patients taking multiple medications may need to devote up to an hour every day to the self-administration of their drops. As part of their regimens, they spend several minutes with their eyes gently closed, performing punctal occlusion, then need to wait an additional five to 10 minutes before their next drop. When they don’t have enough time to wait because life gets in the way, they either skip their medications or use them so rapidly that the drops wash out, even more quickly than drops usually do. I know patients who have to use elaborate alarms and other systems to make sure they remember to take their medications at the right time. Sustained-release therapy, starting with bimatoprost SR, will give glaucoma patients taking multiple medications their time and lives back, and it will improve compliance.

More Efficiency

Besides improving compliance, sustained-release therapy makes treatment much more efficient. Keep in mind that when patients put glaucoma drops in their eyes, most of the medication gets washed into the tear ducts. As a result, maintaining a therapeutic drug level on the ocular surface for an extended period of time is extremely difficult. This is another factor that too often prevents patients from adequately managing their disease, leading to a poor prognosis in many patients diagnosed with glaucoma.7

One study found that the corneal bioavailability of topical ocular medication is less than 5 percent of the delivered amount.8 Compared to topical dosing, bimatoprost SR was found to deliver concentrations of active drug that were 4,400-fold higher at the iris-ciliary body than concentrations produced by topical doses.9 Besides acting directly on the tissue that needs to be targeted inside the eye, medication released by a sustained-release device can keep that medication active inside the eye for longer periods. This also means that much less medication is needed to achieve therapeutic effect. For example, a single bimatoprost SR implant has three orders of magnitude less medication than what’s available in half of a 2.5-ml bottle of topical bimatoprost.

Other factors decrease the efficiency of topical medications. For example, many of our glaucoma patients are elderly and can’t easily coordinate the self-administration of drops.10 Some have tremors and miss their eyes. Others are inexperienced at self-administering the drops or have poor technique. Many have vision that’s so poor that they can’t see the bottle approaching their eyes. A lot of medication is wasted because of these issues, and that waste can be avoided with the use of sustained-release therapy.

Pharmacies are loath to dispense medications early, and insurances may not cover the cost of additional bottles of medication. This leads to treatment gaps for some patients who have difficulty with drops—gaps that can be avoided with sustained-release medications.

The efficiency of sustained-release implants may also allow us to explore new medication classes that would be even less reliant on patient compliance. Sustained-release delivery systems could allow for the use of medications that would otherwise require administration every two to three hours, such as cannabinoids. By using a sustained-release device, you won’t have to worry about the excessive schedules of topical dosing. Implanted sustained-release medications also obviate the need to design drugs to penetrate the corneal epithelium or stroma to access the outflow tract or ciliary body.

Rapidly Growing Field

Additional sustained-release pressure-lowering implants aren’t that far away. Travoprost XR (Envisia Therapeutics) is a biodegradable anterior chamber travoprost implant that’s currently in Phase II clinical trials. The iDose (Glaukos) is a titanium implant that’s anchored to the trabecular meshwork and elutes travaprost into the anterior chamber. This device is expected to be removed and replaced once the drug reservoir is depleted. The iDose is also in Phase II clinical trials. Both implants should provide a therapeutic window of six to 12 months, and early results have been promising.

Multiple other methods of delivering sustained-release formulations of glaucoma medications are also under development.11 Emerging alternative systems that could deliver glaucoma drugs on or near the ocular surface could involve punctal plugs, contact lenses, fornix rings/inserts and nanofiber mats. Subconjunctival implants may also provide sustained, IOP-lowering drug delivery to the tear film or intraocular tissues. A supraciliary route, extending from a suprachoroidal route, could allow for placement of anti-glaucoma drugs in the proximity of the ciliary body. Intravitreal routes could be used to maintain several months of drug retention from depot formulations, including drug suspensions, implants or other delivery systems.

These treatment routes could directly expose targeted tissues to sustained IOP-lowering or neuroprotective treatments. Notably, pharmacokinetic simulations indicate that dosing can be kept lowest when therapy is delivered intracamerally, as it is for bimatoprost SR, but will need to be higher when subconjunctival and ocular surface delivery systems are involved.

Best Patients

Many of the patients I’ve treated with the only sustained-release glaucoma therapy available at this point have found the medication to be a paradigm shift. They love not having to remember to use a drop every day, and they’ve found the implant to be much easier to tolerate than drops. Not needing to remember to self-treat with a topical medication or to tolerate a drop on the surface of the eye makes a big difference to them.

The implant will never be ideal in all circumstances—as no one treatment ever will be. Bimatoprost SR isn’t for patients with active or suspected ocular or periocular infections, a history of corneal disease (including corneal endothelial cell dystrophy), low endothelial cell counts, angle closure, a history of corneal transplantation, absent or ruptured posterior lens capsules and, of course, a hypersensitivity to bimatoprost. I also wouldn’t consider the implant for a young patient who is tolerating his or her medications or only needs a single medication.

On the other hand, even six months of treatment with bimatoprost SR can help some patients significantly. The medication may buy time for a non-compliant 85-year-old patient with respiratory compromise who wants to avoid the operating room until he’s been vaccinated against COVID-19, for example. Likewise, a 72-year-old patient who was recently stented and is taking an anticoagulant could defer surgical management of her co-existing glaucoma until her other conditions stabilize.

Finally, bimatoprost SR may be a good option for a 78-year-old patient with severe ocular surface disease related to excessive topical medications. An implantable sustained-release device may allow her ocular surface to heal and increase the chance of a good surgical outcome.

Looking Ahead

As we continue with the use and development of sustained-release therapy in the care of glaucoma patients, think of the tremendous benefits it provides now and will provide in even greater degrees in the years ahead. Improved compliance, improved efficiency of treatment and the possibility of new medication classes are significant reasons to be optimistic about this emerging modality in glaucoma care.

Dr. Andrew Camp is an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at the Shiley Eye Institute and Hamilton Glaucoma Center, University of California, San Diego. He is also an Allergan study investigator, but has no other relevant financial relationships.

1. Medeiros FA, Walters TR, Kolko M, et al. for the ARTEMIS 1 Study Group. Phase 3, randomized, 20-month study of bimatoprost implant in open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension (ARTEMIS 1). Ophthalmology 2020; 127:12:1627-1641.

2. Craven ER. Comparative data from the ARTEMIS and APPOLLO trials presented at the American Academy of Ophthalmology 2020 Hot Topics presentation, Sunday, Nov. 15, 2020.

3. Craven ER, Walters T, Christie WC, et al. for the Bimatoprost SR Study Group. 24-month phase I/II clinical trial of bimatoprost sustained-release implant (Bimatoprost SR, APPOLLO) in glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology 2020;127:12:1627-1641.

4. Vélez-Gómez MC, Vásquez-Trespalacios EM. Adherence to topical treatment of glaucoma, risk and protective factors: A review. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2018;93:2:87-92.

5. Newman-Casey PA, Blachley T, Lee PP, et al. Patterns of glaucoma medication adherence over four years of follow-up. Ophthalmology 2015;122:10:2010-21.

6. Al-Khersan H, Hussain RM, Ciulla TA, et al. Innovative therapies for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2019;20;15:1879-1891.

7. Davis SA, Sleath B, Carpenter DM, et al. Drop instillation and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018;29:2:171-177.

8. Gause S, Hsu HH, Shafor C, et al. Mechanistic modeling of ophthalmic drug delivery to the anterior chamber by eye drops and contact lenses. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2016;233:139-154.

9. Seal JR, Robinson MR, Burke J, et al. Intracameral sustained-release bimatoprost implant delivers bimatoprost to target tissues with reduced drug exposure to off-target tissues. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2019;35:1:50-57.

10. Singh RB, Ichpujani P, Thakur S, et al. Promising therapeautic drug delivery systems for glaucoma: A comprehensive review. Ther Adv Ophthalmol 2020; 12:25.

11. Kompella UB, Hartman RR, Patil AP. Extraocular, periocular, and intraocular routes for sustained drug delivery for glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 2020; Sep 4. [Epub ahead of print].

Stick With What Works

We absolutely must continue drug development, or we’re doing our patients a disservice.

By Preethi Ganapathy, MD, PhD

Eye drops are no fun. They’re a bane for every glaucoma patient, certainly, but drops are a form of treatment that we, as physicians, know work. We have years of data showing that they prevent glaucomatous vision loss.

I often tell my patients that you have to look at the long game. As a patient, you may be feeling irritation from putting your drops in your eye or from having to use an alarm clock on your phone to remember to take your eye drops two or three times a day. I’m looking ahead to 10 years from now and saying, “What is your visual field going to look like compared to what it could look like if we don’t use these drops?” Now, I definitely think that we as physicians who take care of patients with glaucoma are excited about the introduction of any sustained-release device that can relieve treatment burden from patients. But the question is: For whom should we provide sustained-release treatment and when is the right time? I am going to argue that the answer is not so clear-cut.

Drawing on the treatment philosophy I follow in my glaucoma specialty practice, and established medical evidence, I’ll weigh in on why I think traditional eye drops still come out on top when compared with sustained-release therapy.

Drugs Work

We know drugs. Numerous randomized, prospective studies show that eye-drop therapy prevents structural and functional loss in glaucoma, with many years of follow up. We start eye drops because we know that the data supports their use long-term. So why consider a change? The most significant barriers to our medical treatment of glaucoma are adherence issues, patient burden and ocular surface side effects.

As a community, we’re eager to offer our patients an alternative way to preserve vision—one that doesn’t involve an alarm on a cell phone to remain compliant. So, the question in this point-counterpoint is not, “Will I continue using eye drops in my practice”—of course you will! Rather, “Is it the right time to adopt sustained-release implants and, if so, for whom?”

Drug Development

We absolutely must continue drug development, or we’re doing our patients a disservice. The standard of care for glaucoma treatment has been essentially binary: topical eye drops or glaucoma lasers/surgery. Historically, most ophthalmologists have begun treatment with a topical prostaglandin analogue or beta-blocker, followed by the more burdensome alpha-agonists and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, which are administered multiple times daily.

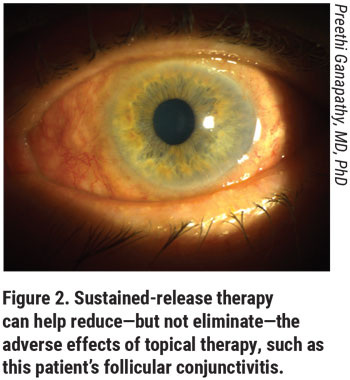

|

Just in the last decade, our treatment options have increased exponentially—and this is exciting! We’ve seen the efficacy of two new classes of glaucoma medications: the rho-kinase inhibitors (Rhopressa, netarsudil ophthalmic solution 0.02%; Aerie Pharmaceuticals) and nitric-oxide donating prostaglandin analogues (Vyzulta, latanoprostene bunod ophthalmic solution 0.024%; Bausch + Lomb).

Both offer the benefit of once-daily administration. Rho-kinase inhibitors are an entirely new class of drug that directly relaxes the trabecular meshwork and increases conventional outflow. Similarly, the nitric oxide donated by latanoprostene bunod has the potential to increase conventional outflow, in addition to the prostaglandin’s ability to improve uveoscleral outflow. Moreover, recent trials have provided strong support for using selective laser trabeculoplasty as first-line therapy, and minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries present a compelling mechanism for lowering intraocular pressure in appropriate cases. Still, to this day, the workhorse of glaucoma treatment is topical ey- drop therapy—and we use it because we know it works.

Is It Our Time?

One thing I think about is that our retinal colleagues have used intravitreal injections and sustained-release treatment implants for a while now. So for those of us who treat glaucoma, the question has been: Where’s our version of anti-VEGF?

Using drops multiple times per day is cumbersome, and there are variable effects if patients forget. As providers, we can’t assess if a medication is working if the patient isn’t taking it. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard patients say, “I fall asleep at odd hours so I can’t remember to take this drop.” Or: “I can’t take this drop. It’s too hard.” I tell them glaucoma is like a full-time job. “You have to remember to take these drops,” I say. There’s no glossing over the message. Granted, a few patients now and then will tell me they don’t mind the drops. But I’ve never had a patient tell me, “Oh this is the best drop I’ve ever had!”

Pharmacologic therapy has to work hard to get from the ocular surface to the target tissues within the eye. The medication has to penetrate the cornea and maintain sufficient and sustained concentrations within the anterior chamber. The concentration of medication within a topical drop needs to be much higher than what actually gets into the eye. So, the surface side effects will be amplified for that reason. With sustained-release treatment, we can bypass some of these sources of patient burden.

Why Sustained-Release?

Sustained released implants include ocular inserts, therapeutic contact lenses, intraocular implants (subconjunctival, intracameral, and intravitreal), and punctal plugs.1 Each of these has its own pros and cons. One expected benefit of the sustained-release treatments in development is that they will decrease drop frequency, sparing patients the challenge of remembering to take drops on time every day. But it’s important to keep in mind that only injectable and intracameral implants promise to alleviate the adverse effects patients experience when they use drops. Sustained-release treatment in most cases is still directed from outside of the cornea, continuing the need for bothersome preservatives and high concentrations of medications to cross the corneal barrier. Ocular surface irritation and drop toxicity remain important concerns that many innovators haven’t solved. In fact, the earliest sustained-release implant developed was a pilocarpine-releasing ocular insert that wasn’t widely adopted because of resulting ocular irritation and not-so-great IOP control.

The bimatoprost SR implant certainly represents progress. Is now the right time to make a change in your practice and use the brimatoprost implant? Possibly. Sustained-release treatment clearly represents the next frontier. It’s exciting to be in ophthalmology at this time because of continuing innovations like this one.

Great Data

The ARTEMIS I and II2 and APOLLO3 prospective trials are well-designed, seminal studies showing that sustained-release implants can lower IOP while reducing these undesirable side effects. In the study, patients received various-sized implants in the study eye and either bimatoprost or timolol drops in the contralateral eye.

The implant bypasses the concern of patient adherence, and injection of the implant into the anterior chamber solves the problem of ocular surface disruption from frequent topical drop and preservative applications.4 Since the intraocular application bypasses the corneal barrier, the concentration of drug in the anterior chamber can be several-fold lower than the concentration of an eye drop. And voila, the drug reaches the target tissue directly.

But for any clinical trial, I’m mindful that patients are carefully selected to accurately reflect the drug’s efficacy. For example, any time you want to inject an implant into the front of the eye, the angle has to be wide enough to accept an implant. Patients with narrow angles are disqualified. Patients who have neovascular glaucoma aren’t included. If someone has underlying inflammation, such as uveitis, or if a patient has cystoid macular edema, bimatoprost SR might not be the right therapy of choice. Patients with uveitis will be given topical prostaglandins if they absolutely need it. Most will tolerate it. But if they’re receiving the prostaglandin via this implant, halting treatment won’t be so easy if they don’t tolerate it well. Removing an implant isn’t as easy as stopping an eye drop.

Moreover, the new delivery systems can only take us so far at this point. Remember that bimatoprost SR replaces one drop for a limited amount of time. The Food and Drug Administration has approved it for a single use, for good reason. Studies have shown bimatoprost SR can reduce IOP for as long as two years in up to 30 percent of patients, which is a great number. On the other hand, if it doesn’t work for two years, you’re either injecting an additional implant off label, which raises its own risks, or you are going back to an eye drop.

Patient Burden

The crux of the argument that we should consider intraocular implants very carefully is simply that we don’t have decades of data yet. Intraocular injections carry the additional risk of corneal endothelial loss, cataract formation, even endophthalmitis. It’s no surprise that this one is approved for only a single use.

Am I suggesting that we abandon all intraocular glaucoma implants because of a small but real risk of endophthalmitis? Absolutely not. If so, our retina colleagues would never use Ozurdex (dexamethasone intravitreal implant), sticking only to topical steroids. Using our first implant to deliver a prostaglandin only makes sense because good data supports the efficacy of a prostaglandin. But practically speaking, bimaroprost is a once-daily drug. When implants hold medications typically dosed two to three times daily, we’ll have another game-changer for patients.

The cost of the bimatoprost SR is another potential concern because it can be quite steep for the patient. If a patient has Medicare, and no secondary insurance, depending on the facility where the treatment is administered, a single implant can cost up to $800. Meanwhile, latanoprost costs a patient $10 per bottle without insurance. These are all factors that we must analyze carefully as we try to match our patients to their ideal drug treatments.

Finally, the adoption of intraocular injections will place a practice burden on the physician. Workflow will need to be adjusted to accommodate the extra steps of informed consent, patient positioning, appropriate pre-procedure protocols and post-procedure care. This translates into a significant time and staffing burden.

My Verdict?

Will I use this first sustained-treatment for my patients? Perhaps under limited circumstances. As a glaucoma specialist, before I begin to use a bimatoprost SR, I need to consider that most of my patients are taking multiple drugs. As I mentioned, this implant replaces only one of them. I certainly will never turn away from advances that might help my patients. But I will also continue to use all of the tools—including topical therapy—that I have been using for years to keep them stable. REVIEW

Dr. Ganapathy is an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the Center for Vision Research, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y. She reports no financial relationships.

1. Kompella UB, Hartman RR, Patil AP. Extraocular, periocular, and intraocular routes for sustained drug delivery for glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 2020; Sep 4. [Epub ahead of print].

2. Medeiros FA, Walters TR, Kolko M, et al. for the ARTEMIS 1 Study Group. Phase 3, randomized, 20-month study of bimatoprost implant in open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension (ARTEMIS 1). Ophthalmology 2020; 127:12:1627-1641

3. Craven ER, Walters T, Christie WC, et al. for the Bimatoprost SR Study Group. 24-month phase I/II clinical trial of bimatoprost sustained-release implant (bimatoprost SR, APPOLLO) in glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology 2020;127:12:1627-1641.

4. Seal JR, Robinson MR, Burke J, et al. Intracameral sustained-release bimatoprost implant delivers bimatoprost to target tissues with reduced drug exposure to off-target tissues. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2019;35:1:50-57.