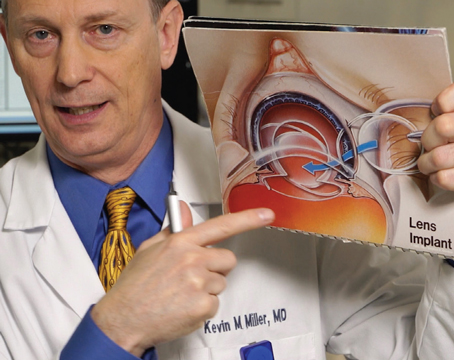

In the fall of 2001, investigators began preliminary trials in the United States for Anamed's PermaVision lens insert for the treatment of hyperopia. Though only a small number of U.S. patients have received the lens in the trial so far, surgeons both here and abroad have learned more about how to implant the device. Here's an update.

The Lens's Design

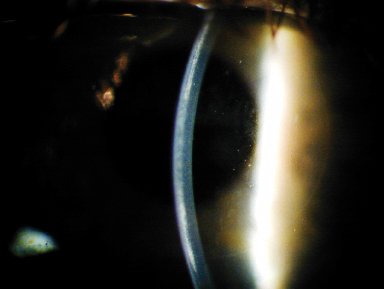

The PermaVision lens is made from a material called Nutrapore, a hydrogel substance that's 78 percent water. The lens in the U.S. trial is 5 mm wide and 30 to 60 µm thick in the center. Lens powers are increased by thickening the center of the lens.

After implanting four of the 10 lenses in the the U.S. Food and Drug Administration study, Northridge, Calif., surgeon Mitchell Shultz says there's been no corneal toxicity from the lens.

The idea behind using the lens to treat hyperopia relies on increasing the relative steepness of the central cornea by inserting the disc beneath a LASIK flap.

Implantation

According to Anamed CEO Alok Nigam, PhD, most of the complications that have occurred with the lens are a result of either the delivery system or the technique the surgeon uses to implant it. He says both of these issues are being worked on, and expects future cases to yield better results.

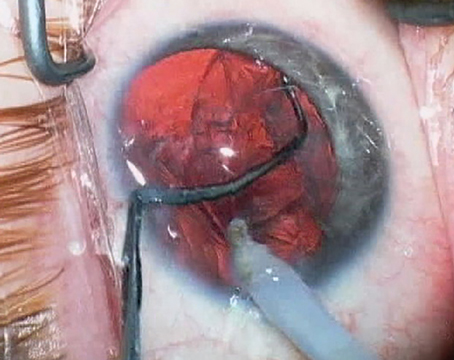

|

| Corneal haze that resulted from a "dry" implantation technique. |

"On surgical-grade steel, the lens material didn't slide efficiently," says Dr. Nigam. "Surgeons had a lot of difficulty transferring it from the spoon to the cornea, resulting in the insert being damaged or inverted. Using fluid to dislodge it from the spoon might also result in too much fluid on the cornea and subsequent corneal edema." The new spoons will be made of titanium.

"The titanium spoon has a matte finish, so it's a low-resistance surface," asserts Dr. Nigam. "You can basically touch the lens to the cornea and it will transfer from the spoon."

The other problematic part of the procedure was whether to use a "dry" or a "wet" technique for implantation. Some surgeons thought a wet technique, which involves irrigating beneath the flap before lifting it, contributed to the lens decentering immediately after the procedure.

In response, Dr. Shultz and some of the others working with the lens tried a dry technique, avoiding the irrigation step. This technique, however, had problems of its own.

The surgeons discovered that, by not irrigating, tissue debris remains in the interface and can result in peripheral haze that's visually insignificant and, sometimes, central haze that causes lost lines of vision. The wet technique has now become part of the standard protocol.

"We've always used a wet technique," says Houston surgeon Stephen Slade, the other U.S. investigator. "We were happy with our results, and we're now teaching other surgeons to do it that way."

Once the lens is under the flap, the surgeons say they try to leave it alone. Dr. Shultz says he dries the flap edges with a Merocel sponge but doesn't actually touch the lens. He also squeegees over the top of the flap with the sponge.

Current Results

Only a limited number of eyes have received the lenses in the United States, but more have been implanted in other countries.

In a study by Jedda, Saudi Arabia's Akef El-Maghraby, MD, 29 consecutive patients with 1 D to 6 D of hyperopia underwent implantation. Of the 93 percent (27 eyes) available for follow-up at one year, 44 percent were within 0.5 D of the intended refraction and 78 percent were within 1 D. Only 37 percent saw 20/20 or better uncorrected, though, and 74 percent saw 20/40 or better. Though no eyes lost two or more lines of best-corrected vision, 14 percent (4 eyes) had dislocated lenses immediately after the procedure that needed to be repositioned. In his paper, Dr. El-Maghraby says a longer follow-up will be necessary to gauge the long-term results. (El-Maghraby A. ASCRS, 2003.)

(Additional visual results from international implantations appear in Table 1.)

Though dislocations occurring immediately postop have been relatively high, in the 10-percent range in 93 international cases, Dr. Nigam says that, once the initial dislocated lenses were recentered, there have been no further decentrations.

| Table 1. International Implant Results | ||||||

| . | FDA Laser Requirement |

Results | ||||

| . | . | 3 mos. | 6 mos. | 12 mos. | 18 mos. | 24 mos. |

| PREDICTABILITY | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Manifest refraction ± 0.5 D | 50% | 53% | 52% | 68% | 67% | 100% |

| ± 1 D | 75% | 75% | 74% | 80% | 92% | 100% |

| STABILITY | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Change < 1 D for 3 mos. | 95% | n/a | 92% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| EFFECTIVENESS | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| UCVA >/= 20/40 | 85% | 86% | 86% | 88% | 100% | 100% |

| SAFETY | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| BSCVA loss >/= 2 lines | 5% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Preop BSCVA >/= 20/20 but postop </= 20/40 | 1% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| >/= 2 D induced cyl. | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Decentrations | -- | 10% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| POPULATION (Total N = 93) | -- | 76 | 58 | 41 | 12 | 4 |

| Post-op MRSE (pre-op 3.57 D) | -- | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.11 |

Areas that may still need work are in the safety category. Since some surgeons used the dry technique in the 93 international cases, the percentage of patients who saw 20/20 best-corrected preop but who see 20/40 postop is 2 percent, 1 percent higher than the U.S. FDA's safety requirement for refractive lasers. Dr. Nigam thinks that this will change as surgeons become more proficient. "The numbers will change as they adopt the wet technique," he says. Also, the stability of refraction doesn't exceed the FDA guideline until 18 months postop.

In the 10 U.S. eyes, the average refractive error was +3.5 D, with a maximum of +5 D, and mesopic pupil size could be only 5 mm.

"We're not sure how much of an issue pupil size is," says Dr. Shultz. "However, since the current lens achieves a functional 5.5-mm optical zone, we've limited it to patients with 5-mm pupils."

Two of the 10 U.S. patients were undercorrected and required explantation. One of the two had haze that resolved after the explantation.

Dr. Slade says his small group of six patients didn't have any dislocations and only trace corneal haze. He emphasizes, though, that this is a limited number of patients, and more research will be necessary.

One of the issues Dr. Shultz had with the first phase of the PermaVision study was that patients were only allowed to have one eye done. "A couple of the Phase-1 patients were contact-lens wearers who could wear their lenses, but one patient, a +2, just walked around blurry after the surgery," he says. In the second phase of the procedure, though, he says the patients will be able to receive a different refractive procedure in their fellow eyes.

The data on the 10 U.S. patients was submitted to the FDA in April, and Anamed is currently speaking with the FDA on how the agency wants the company to proceed with the second phase.