As ophthalmologists, we tend to think of preserving vision as our primary responsibility. But the reality is that many of our patients will lose vision despite our best efforts, and that loss brings with it a host of challenges that can undermine a patient’s quality of life and functionality. I would argue that, as physicians, our true responsibility is not just to preserve vision but to help our patients maintain functionality and quality of life. Maintaining the patient’s vision is simply a means to that end.

Helping patients maintain their functionality and quality of life is well within our abilities as doctors. However, in order to do that we have to be thinking about more than simply managing the patient’s vision. We have to remember that our goal is to treat the patient, not just the disease.

Physician, Heal Thy Patient

As doctors, we’ve become more powerful at manipulating the manifestations of disease, but I don’t think we’ve become any better at understanding how to care for the people who have the disease. For example, I frequently see articles on how to manage glaucoma, but I seldom see articles on how to care for patients who have glaucoma. The difference is huge, and rarely recognized.

At the practical level, treating the patient rather than the disease means considering what’s important to the individual patient and keeping that in mind when deciding how to proceed. Consider the different effects a disease of the eye can have on an individual: The patient can have a symptom, such as pain; you may observe a sign such as a cupped optic nerve, a hemorrhage in the macula or high intraocular pressure; the disease may undermine the patient’s visual ability, as registered by a specific metric such as visual acuity, contrast sensitivity or visual field; and/or the disease may undermine the person’s ability to function. Of these, only two really matter to the patient: how the patient feels, and how well the patient is able to function. Patients don’t care about signs. Their IOP or the fact that they have a hemorrhage on the optic nerve is totally immaterial to them. (Of course, they will care a great deal if you explain that these signs indicate progressive glaucoma that could lead to blindness; but the reason they will care is because you’re now talking about their functionality and quality of life.)

I believe a doctor’s primary job is not just to treat disease, but to care for how people feel and how they function. Patients may understand that something has improved because of your treatment—after all, you’ve undoubtedly told them so—but what they really want from you is improved functionality and quality of life. That may or may not happen as a result of your treatment. Visual ability, as reflected by the patient’s ability to read a Snellen chart, for example, doesn’t necessarily translate to greater functionality or better quality of life.

This is one reason treating the patient is so different from treating the disease. The necessities of how each person has to function in order to get through the day vary widely; the functional needs of a professor may be quite different from the needs of a truck driver or a person managing a farm. As a result, some people’s ability to function effectively in daily life may not correlate well with how that person does when taking the visual tests we typically conduct in the office.

Why We Focus on Disease

|

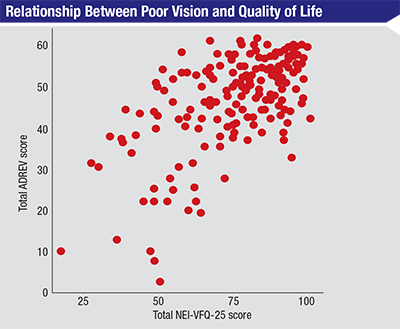

| Patients faced with the prospect of poor vision often assume their quality of life will drop dramatically as a result, but that is not necessarily true. This graph compares the ability to perform activities of daily living (y-axis), as measured by the individual’s score on the Assessment of Disability Related to Vision scale (where 63 is the best possible score), to the individual’s National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire score.6 The large point spread indicates that some people with limited vision have an excellent quality of life, while some who have very good vision do not. Challenging patients’ assumptions can help to alleviate some of their fears and emotional suffering. |

• We want to have a beneficial effect, and a change in a metric “proves” that we did. Having a beneficial effect is what we’re being paid for. So if you take out a cataract, the patient’s vision may go from 20/80 to 20/20, and you can say that you’ve made things better for the patient. However, the patient could end up with more glare than before, and that may be more important to some patients than improved acuity. So even though a standard metric says you’ve had a beneficial effect, you may also have changed the patient’s vision in a way that lowers the patient’s quality of life. The patient may end up quite unhappy.

In this situation the doctor can point to the metric that says the patient’s vision is better, but doing so indicates a misunderstanding. The metric doesn’t say you’ve made the patient better; the metric says you’ve made the patient’s visual acuity better. It’s not the same thing. (Of course, asking the right questions ahead of time might have revealed the patient’s priorities and allowed the surgeon to modify his approach, preventing this unhappy outcome.)

• Finding out what matters to the patient isn’t always easy. Another reason we tend to focus on the disease is that much of the information that can help us treat the whole patient comes from taking the history, which is by far the most difficult part of an evaluation. Patients often do not say what they really think. If you ask some glaucoma patients how they’re feeling, they’ll say they feel just great. You may see clear indications of visual difficulty, such as the patient having trouble finding the exam room chair or failing to respond when you hold out your hand to say hello. But if you comment on this, some patients will say “Oh no, that doesn’t bother me.” Meanwhile a quick check with the person who accompanied the patient to the exam may reveal that outside of the exam room the patient complains constantly about how miserable his visual disability is making him.

Of course, some patients present the opposite problem. I’ve had patients who complained that they were going blind every time they came in to see me, although I could never find a change in their measurements. I usually give the patient the benefit of the doubt and say that something must be going on; then I explain that I can’t address it without being able to identify what it is. But I wouldn’t dismiss the complaint. The patient’s quality of life matters—not just the state of the disease—so if the patient is unhappy enough, I’d recommend that the patient get some other kind of assistance dealing with the symptoms she’s experiencing.

• Our time with patients is more limited than ever. In the past, an ophthalmologist might have spent 15 to 30 minutes with a patient. Today most doctors have to move patients through their practices much more rapidly. If they don’t, they can’t generate enough return to cover their increasingly expensive office overhead. That encourages focusing on test results rather than the patient’s functionality or quality of life.

I was recently in Germany, where I visited an office that pushed this idea to the limit. Patients went into a room with one table and one chair. The table has three instruments attached, intended to measure three things: IOP (without using drops), visual acuity and central corneal thickness. The doctor wanted those three pieces of information for every patient. So, the patient simply swung the chair around to have the three things tested. This allowed three billable tests to be done within five minutes.

Taking a history can be a more time-consuming way to earn reimbursement, but it’s often more important in terms of revealing the patient’s situation and real needs.

• Many doctors don’t feel responsible for assisting the patient with his experience of the disease or disability. A physician might point out that a given patient is a grumpy old man, and say “What responsibility do I have for the fact the macular degeneration is making him miserable? I treated him with Lucentis and his vision improved from 20/60 to 20/40. I did a great job. It’s not my fault that he’s unhappy.” My response would be that it IS our responsibility to do what we can to make patients less miserable—not just rein in their disease. Dr. Stetten, I think, would agree. Quality of life, without question, is the thing that matters most to our patients.

• Most physicians aren’t trained to manage patient attitudes. This may be true, but it’s not a reason to ignore the patient’s problem. If you feel unqualified to help the patient deal with his anxiety, depression or trouble functioning, tell the patient that you can see he is having difficulty and suggest options for getting help from other sources.

Taken together, the factors listed above create a kind of perfect storm. They push doctors away from thinking about the patient’s functionality and quality of life, shifting the focus toward just managing the disease. They encourage us to worry about objective measures such as a change in visual acuity, OCT or IOP. It’s important to remember that those measures are merely surrogates for the thing that really counts: how the patient is feeling and functioning.

Deciding How to Proceed

Clearly, vision impairment has an impact on functionality and quality of life. However, the impact that visual impairment has on any given individual depends on a number of factors that are within the physician’s power to influence, including the patient’s attitude and use of resources. To truly help our patients, we have to avoid letting our objective measures blind us to how the disease—and our treatment—are affecting the patient’s functioning and quality of life.

| It’s important to remember that [our] measures are merely surrogates for the thing that really counts: how the patient is feeling and functioning. |

First, we need to evaluate how the disease is impacting the patient’s quality of life and ability to function. Your evaluation may be based upon your observations and patient responses to questions, but there are also quantitative ways to assess this. I have a conflict of interest here (although not a financial one) because I’ve been involved in the creation of a clinical test for assessing the effect of visual loss on the ability to perform activities of daily living. The test, which involves detecting motion, reading signs, finding objects and navigating an obstacle course, takes 14 minutes (on average). It was evaluated in a recent study which found that the results correlated well with other measures used to evaluate people’s changes in quality of life, including the National Eye Institute’s Visual Functioning Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25).2 At this point, such tests are not in wide use, so this is certainly not the standard of care. However, what this test reveals says a great deal about how the disease is affecting the patient’s quality of life, so my hope is that a test of this type will eventually become just as standard as tests measuring visual acuity.

Second, once you’ve made your assessment—as subjective and imprecise as it may be—you have to decide whether the effect the disease is having on the patient is a significant issue for the patient. If it appears to be impacting the patient’s quality of life and functionality, the patient may need help dealing with it. In some cases, it may tough to determine if the patient really does need help; but in other cases it will be clear that the patient is having trouble and needs counseling or some other form of assistance. If it’s clear that the patient would benefit from additional help, you have to decide whether this is something you can provide. In many cases I do try to counsel the patient myself. I’m not a trained counselor, but if this is a person I’ve been working with for a period of time and I believe she has trust and confidence in me, I may be able to help.

For example, I know a little about current low-vision aids. So I can say, “There are computer devices you can use to help you read; would you be comfortable going online to look at those?” Most of the time patients are happy to follow that lead. So in some cases it may not be necessary for me to refer the patient to another doctor or service.

If you’re not comfortable trying to help directly, you have to decide what referral resources would be most appropriate. If the person is having trouble functioning because of reduced vision, you can suggest that she see a low-vision specialist you respect. It’s great if you can honestly say, “I’ve sent other patients to Dr. Smith, and she is a wizard at helping people come to grips with this type of change. I don’t have as much experience helping people with that as she does, and it’s clear that this is really bothering you. So I’m going to send you to see her.”

In other cases, it might be appropriate to refer the patient to a low-vision center; to a pastoral service, if the patient has strong religious beliefs; to a social service agency, where the patient might find help with issues such as getting to and from the doctor’s office and managing his socioeconomic situation; or to an agency such as Associated Services for the Blind, where the person can get a battery of assessments, be evaluated for the use of a cane or guide dog and learn how to do laundry and other chores that might be challenging to manage with limited vision.

The Doctor’s Perspective

In general, doctors do a better job of treating the patient—not just the disease—if they keep several things in mind:

• When making medical choices, remember that the goal is to maintain the patient’s quality of life and functionality. In the case of managing glaucoma, this would include not overprescribing eye drops that may ultimately injure the cornea and degrade the person’s vision. Remember: The goal is not to keep the patient’s IOP low, or even to preserve the visual field. The goal is to maintain the patient’s functionality and quality of life. If the treatment undermines that goal in the name of lowering IOP, you haven’t done the patient a favor.

• Never underestimate the value of counseling for patients faced with vision loss. A randomized, controlled study conducted by Barry Rovner, MD, and William Tasman, MD, in the department of psychiatry at Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience in Philadelphia, demonstrated the importance of counseling for patients with macular degeneration.3 Two hundred sixty-five patients age 65 or older with pre-existing macular degeneration in one eye and a recent diagnosis of neovascular macular degeneration in the other eye were randomized into two groups, one of which received six sessions of problem-solving therapy in their homes; those in the other group received standard care. At two months, subjects who received counseling were half as likely to have a depressive disorder (11.6 percent vs. 23.2 percent, p=0.03). The counseling also reduced the likelihood that the patient had given up a valued activity (p=0.04). At six months, the beneficial effects had diminished, but subjects that received counseling were less likely to be suffering from persistent depression (p=0.04).

The message is clear: Getting counseling for patients in this kind of situation can make a significant difference in their quality of life.

|

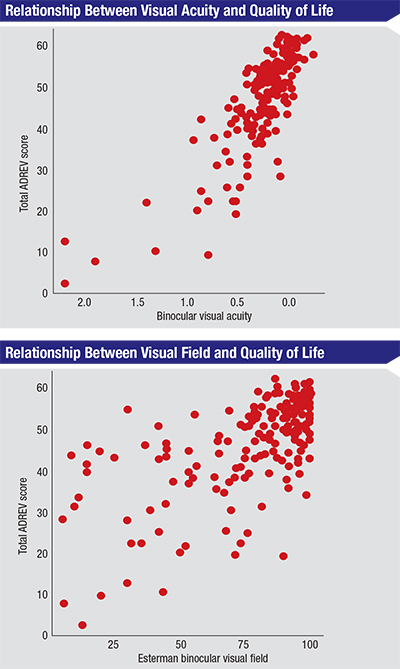

| Some types of vision difficulty are more likely to impact quality of life than others. The graphs above show that an individual’s visual acuity has a much more pronounced impact on quality of life (as measured by the Assessment of Disability Related to Vision score) than the status of the individual’s visual field.6 |

• Don’t let the impact of new treatments overshadow the patient’s situation. The medical profession has a long history of treating diseases rather than patients, and that tendency may be growing stronger over time, thanks our increasing ability to address disease. When Dr. Stetten saw his doctor about his macular degeneration, for example, there was no way to treat the disease. That’s not the case today; now, we can improve vision in many patients we were powerless to treat in the past. Unfortunately, that may push us even further toward focusing on treating the disease rather than thinking about the patient as a whole.

No matter how miraculous your treatment may seem relative to what you could do in the past, the patient’s functionality and quality of life is still the bottom line.

• Remember that vision loss impacts everyone differently. We usually assume that there is a close correlation between change in visual function and change in quality of life. There are indeed studies that show such an association—but the strength of that association is going to depend on the patient.

Years ago I reviewed a paper sent to me by a European journal about a group that had developed a quality-of-life survey for people who lived in Mali.4 They hypothesized that quality-of-life surveys had to be culturally relevant in order to be valuable. Because there was no culturally relevant survey for the people who lived in Mali—most quality-of-life surveys were designed for people living in urbanized Western countries—they developed a survey they thought was appropriate and administered it.

I still clearly recall one of the graphs from that paper. Although there were some flaws in the data presentation, the graph showed something remarkable: The correlation between visual ability and quality of life changed depending on where in Mali you were living. If you lived in a city in Mali and your vision got worse, your quality of life got worse. If you lived in rural Mali, that correlation largely disappeared; there, if your vision deteriorated, your quality of life didn’t change much. To me, that was an enormously important study. It provided a striking example of the reality that visual disability does not always correlate with a reduction in quality of life, and the presence or absence of that correlation can be affected by something as simple as where you live.

We can’t assume that we know how a change in vision is going to affect a given patient. If vision drops from 20/20 to 20/40, some patients won’t mind much; for others, it might make them suicidal and in need of counseling. So part of our job is to ask the patient how she feels about the current symptoms, as well as potential future symptoms such as loss of vision. It’s absolutely imperative that we not assume we know what the patient is feeling. To care for the patient—not just treat the disease—we have to ask.

• Remember that different types of vision loss affect functionality to a greater or lesser extent. When managing glaucoma, loss of visual field is something we monitor on a regular basis. Yet studies have demonstrated that loss of visual acuity has a more profound effect on most types of functionality than loss of visual field does. The top chart on p. 43 shows the relationship between acuity and functionality as measured by the Assessment of Disability Related to Vision test. (This test measures a person’s ability to do things such as read a sign at a distance and recognize faces; a higher score indicates better function.) The second chart shows the relationship between the subject’s visual field and the same functionality score. The scatter is greater in the second chart because the correlation between loss of visual field and functionality is not as great.

There’s one important caveat to trying to treat the whole patient: Taking your patient’s situation and perspective into account does not mean that you should respond to a subjective complaint with medical or surgical treatment—unless you find measurable signs of a problem. If the patient’s visual acuity has gone from 20/20 to 20/60, that’s hard information, the kind that would stand up in court. If the patient says her vision is worse, but you can’t document it in any way, doing a cataract extraction, for example, could backfire if the outcome isn’t ideal. You could find yourself in the very difficult situation of trying to convince yourself (much less a court) that you acted properly on the basis of subjective information. You should still take the patient’s complaint seriously, but if you can’t find hard evidence to support it you could be on shaky ground responding with medications or surgery.

Getting the Big Picture

When you realize that one of your patients is struggling with vision loss—or fear of vision loss—taking these steps will help you get a clearer picture of what’s happening:

• Ask about your patient’s reaction to his vision impairment—and really listen to the answer. It’s common for people in this situation to worry about losing their job and fear that they’ll become dependent. Some people feel guilty, as if the vision loss was punishment for past errors; some become angry, asking “Why me?” Simply listening to the patient’s concerns can do a lot to give the patient hope, and it will help to guide your choices for recommendations if it becomes clear that your patient needs assistance. Of course, you probably don’t have the time to become your patient’s emotional counselor, but the act of listening helps.

• Inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, especially in terms of how much time he spends alone. A patient who is isolated is likely to be in greater need of assistance, both psychological and physical. It may be that the caregiver who brings the person to your office isn’t around at any other time. The patient may be very much alone and in need of human contact.

• Ask about how the people in the patient’s circle of contacts are reacting to the patient’s vision loss. If the family or friends of the patient are not being supportive, getting the patient outside assistance might be especially helpful. Even more important, close relationships such as living with a spouse are likely to change as a person loses vision and become more dependent. On the one hand, the spouse may feel validated in the marriage for the first time because she can do things for her husband that she wanted to do all along but was never able to do. He may be happy about it too. On the other hand, she may have her own life and feel stressed by his sudden dependence on her. This can lead to a relationship becoming hostile or breaking down.

Very few ophthalmologists are going to ask a patient with macular degeneration who is not responding well to treatment, “How is your marriage going? Is it still OK?” But it may be a very important question to ask, because it may be the opening the patient needs to admit that his marriage is in trouble. The ophthalmologist can say, “I’m not the best person to counsel you about that, but it’s not rare that patients have difficulties when one of them loses vision. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. You may want to bring that up with your primary care physician, or seek some kind of counseling. Getting help managing this change could make a big difference.” Just getting that far could go a long way toward helping your patient.

Helping Patients Manage

Although we may not have the time or skills to provide professional counseling, a few simple strategies can go a long way toward improving your patient’s quality of life.

• Provide encouragement, hope and perspective. When faced with loss of vision, people often react with depression and despair. It can be helpful to provide a gentle reminder that, like many things in life, a setback can have positive consequences as well as negative ones. It’s also worth reminding patients that situations we encounter—positive or negative—seldom have the huge impact we expect them to. Achievements we thought would make the rest of our life blissful often fall short, and disasters we thought we couldn’t possibly survive turn out to be manageable—and sometimes even produce unexpected benefits.

| When faced with loss of vision, people often react with depression and despair. It can be helpful to provide a gentle reminder that, like many things in life, a setback can have positive consequences as well as negative ones. |

• Sharing a story or two may help some patients. I’ve known individuals who lost most of their vision but still were cheerful and accomplishing impressive things. One woman who was nearly blind informed me that she had just graduated from law school, first in her class. A woman psychotherapist in Hong Kong who lost her sight at age 8 as a result of Stevens-Johnson syndrome has written that her blindness ended up becoming a blessing. “There are lots of challenges, but the benefits are greater,” she wrote. “I experience blessings around me every day and everywhere even though I can’t see. My blindness opened my eyes in a different way.”5 On the other hand, I’ve seen people with minimal visual disability who labeled themselves “disabled” and gave up on life.

Handled in a positive way, a setback in vision can end up leading to positive changes in a person’s life. That’s the kind of attitude that needs to be encouraged, and sharing stories like these can sometimes help.

• Consider having the patient speak to another patient who has done well. If another patient you know well has been in the same situation—and is a good communicator—this can be helpful. However, it’s important to check with the other individual first and make sure he’s willing to share his experience before putting the patient in touch with him.

• Remind your patient that attitude can make a big difference in how well things turn out. Even though quality of life and functionality are closely related, they’re not the same thing. Quality of life is a feeling we have about our functionality. How do I feel about the fact that it’s becoming hard to drive? For some people, no longer being able to drive would be horrifying, resulting in a devastating decrease in their quality of life. Others wouldn’t care that much; it might be a great excuse to get their daughter to drive them around, which would make them happy. So the same loss of functionality can have a very different impact on quality of life for different individuals.

Loss of sight is a challenge, and like any challenge, how you cope with it will depend in large measure on the way you frame the situation in your mind. What people sometimes forget is that the perspective we have about our situation is always under our control. That’s why it’s worth reminding your patient that making the effort to look for potential positives in a difficult situation caused by vision loss can remove some of the fear and difficulty. Then, despite some loss of functionality, the impact on the patient’s quality of life won’t be as great.

Moving in the Right Direction

Fortunately, there is now a growing interest in treating the patient as well as the disease. This is especially evident in some areas such as cancer treatment. I often see advertisements inviting patients to choose a particular cancer treatment center because the doctors “focus on the whole patient”; doctors at that center are willing to consider alternate treatments such as meditation and options beyond chemotherapy and radiation. I think that’s a step in the right direction. It’s saying, “You are not a cancer—you are a person who has cancer.” We need to move in the same direction: “You are not a case of glaucoma. You are a person I’m trying to help who happens to have glaucoma.”

Seeing our goal as treating the patient—not just the disease—is a simple change in perspective. But it’s a change that can make a world of difference; it can change how effective we are at helping our patients to end up with happier and more effective lives. REVIEW

Dr. Spaeth is the Louis J. Esposito Research Professor at Wills Eye Hospital/Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.

1. Stetten D. Coping with Blindness. N Engl J Med 1981; 305:458-460.

2. Wei H, Sawchyn AK, Myers JS, Katz LJ, Moster MR, Wizov SS, Steele M, Lo D, Spaeth GL. A clinical method to assess the effect of visual loss on the ability to perform activities of daily living. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:5:735-41.

3. Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT, Leiby BE, Tasman WS. Preventing depression in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:8:886-92.

4. Schémann JF, Leplège A, Keita T, Resnikoff S. From visual function deficiency to handicap: measuring visual handicap in Mali. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2002;9:2:133-48.

5. South China Morning Post, February 2, 2015, p. 20–22.

6. Altangerel U, Spaeth GL, Steinmann WC. Assessment of function related to vision (AFREV). Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006;13:1:67-80.