Prior to the 21st century, penetrating keratoplasty was the only corneal transplantation technique available for Fuchs’ dystrophy, endothelial dysfunction and other corneal diseases. When endothelial keratoplasty was first developed, it supplanted PK for many of these diseases. Over time, endothelial keratoplasty procedures such as Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty began to be more prominent in corneal transplantation. Today, PK procedures are slowly declining, but they still exist. In this article, corneal surgeons will explain how PK is being used and why it’s not the foremost procedure for all corneal diseases.

Endothelial Keratoplasty

There are different procedures under the umbrella of keratoplasty. Historically, PK has been the tried-and-true technique for surgeons, Involving a full thickness corneal transplantation where a diseased cornea is removed and replaced with a healthy donor cornea.1 Then, in the early 2000s, EK took off.

“Most surgeons doing a lot of corneal transplants converted around ’03, ’04 and ’05 because most of the transplants we were doing were for endothelial dysfunction,” says Sadeer Hannush, MD, an ophthalmologist at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. “For all who’ve trained in the ‘80s and ‘90s, we were longing for a procedure that wouldn’t replace the entire cornea when the abnormality was only in the endothelium.”

DSEK was the first procedure to make waves in corneal transplantation surgery. This technique was developed in 2004 by Dutch surgeon Gerrit Melles, MD, PhD. For this procedure, a smooth surface is created for graft application and the source of disease is removed, all while sparing posterior stroma.2

“When it first came on the scene 25 years ago, it was the easiest way to address Fuchs’ dystrophy or endothelial dysfunction because the previous procedure that had been used always was PK,” says William Culbertson IV, MD, of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. “The advantages of DSEK are that it requires a small incision, the eye isn’t exposed openly [during surgery] and the patient often has recovery of good vision without any significant induced astigmatism within a couple of months, rather than a year or two [with PK].

“Also, the eye is much more secure because the incision is four or five millimeters in diameter as compared to a 360-degree full-thickness incision,” Dr. Culbertson continues. “The other advantage is that if the graft fails, it could be easily replaced with the same outcome of good vision.”

|

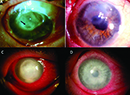

| (Top Left) Postoperative appearance of patient who underwent DMEK for Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy at one week post-operatively with residual anterior chamber gas bubbles. (Top Right) Postoperative appearance of patient who underwent DMEK for Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy at two weeks postoperatively with complete resorption of the gas. (Bottom) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography demonstrating a limited, peripheral graft-edge lift one week after DMEK surgery (right side of image). The attached portion of the graft mimics normal anatomy due to the precise one-to-one replacement of tissue with DMEK. Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.en. No changes were made. (Courtesy Antoinette Venckus, CRA) |

DMEK, which was developed years after DSEK, is a more delicate procedure than other EK techniques. Interestingly, Dr. Melles was behind the development of DMEK in 2008 as well. Both DSEK and DMEK target Descemet’s membrane, but DSEK removes a part of the posterior stroma, while DMEK does not.3 The graft for DMEK is around 10 to 15 µm in thickness,2 while graft thickness for DSEK can be nanothin (15 to 49 µm) all the way up to a conventional size (150 to 250 µm).4

Out of all keratoplasty procedures, DMEK results in the most positive outcomes for endothelial disease cases. In 2019, researchers compared long-term graft survival outcomes and complications of patients who underwent DMEK, DSEK and PK for Fuchs’ dystrophy and bullous keratopathy. One hundred twenty-one eyes underwent DMEK, 423 eyes underwent DSEK, and 405 eyes underwent PK. Patients who received DMEK had the best overall graft survival of 97.4 percent, compared to DSEK (78.4 percent) and PK (54.6 percent).5 Additionally, DMEK had the lowest rate of graft rejection of 1.7 percent, compared to DSEK (5 percent) and PK (14.1 percent).5

What makes DMEK a far more advanced EK procedure is its effective recovery time. “In terms of stability and anatomical recovery time, it would most certainly be DMEK because when it’s done properly, the ability of the new endothelial cells to pump the cornea clear and compact and have improved vision is over within a matter of a couple of weeks,” says Kenneth Kenyon, MD, of Eye Health Vision Center in Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

“As the field of cornea has grown more advanced, we’ve learned how to replace the specific layers of the cornea that are diseased,” explains Zeba Syed, MD, Director of the Cornea Fellowship Program at Wills Eye Hospital. “So, instead of replacing the entire cornea regardless of the layers involving disease, we can now do a layer-specific transplantation. The evolution over time reflects (1) newer surgeries, (2) people getting more comfortable with the newer surgeries and (3) improvement of techniques overall.

“People are increasingly performing EK procedures because eye banks have become very good at pre-stripping, pre-loading, pre-staining, and pre-cutting the tissue, so it makes it very easy to complete,” Dr. Syed continues.

Experts explain the differences between DMEK and DSEK: “To get the tissue to stick, we have to inject the transplant into the eye and then we put a bubble underneath it, because we’re just replacing the back layer of the cornea,” says Dr. Syed. “We either use air or gas and we inject it under the transplant, and we have the patient lay flat for several days face up depending on what kind of transplant: DSEK I usually do two days, and for DMEK I usually do three to five days of lying flat.

“There’s always a conversation about when we should do a DMEK versus a DSEK,” Dr. Syed adds. They both are EKs, they both treat endothelial disease, but they’re different in their technique. The tissues are different in thickness, and in general a DSEK is easier to perform because it’s a thicker tissue so it’s easier to handle, DMEK is the one with the steeper learning curve because it’s really thin tissue and harder to maneuver intraoperatively.”

Dr. Hannush adds that DSEKs aren’t always favored over DMEKs. “In Germany, for example, 98 percent of the endothelial grafts are DMEK,” he says. “Now you may say, ‘Are they better surgeons?’ What people don’t know in America is that in Germany all DMEKs are done in the hospital and are admitted for six to nine days. We’re lucky to keep our patients in the surgery center for five hours. So, they go home, they don’t follow any instructions, they’re not lying flat on their back, and so on and so forth.” Basically, German surgeons can opt for DMEK, which provides a better visual outcome over other procedures, because they have more control over the postoperative outcome than American surgeons.

|

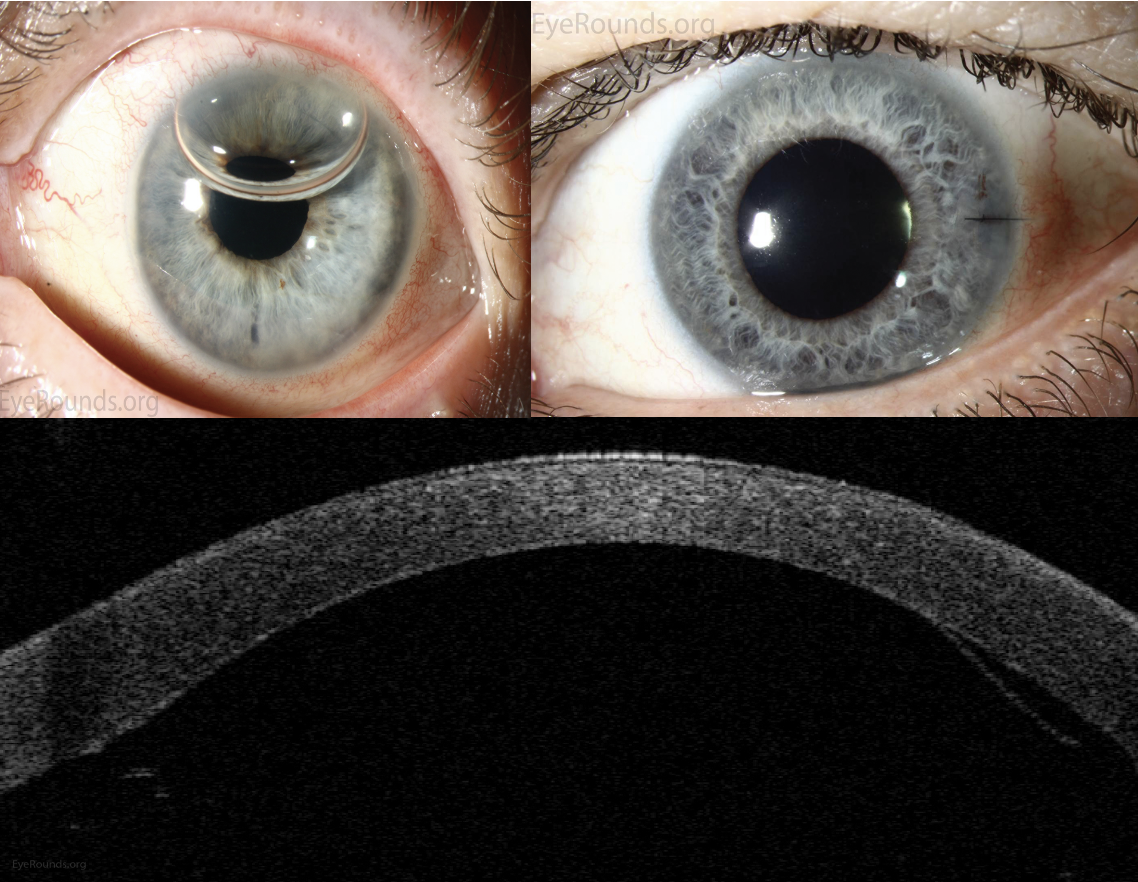

| (Top Left) The DSAEK grafts can be visualized as a subtle ring in diffuse illumination. (Top Right) The DSAEK grafts can be seen protruding posteriorly from the cornea in the inferior aspect of the slit beam. (Bottom) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography demonstrating an attached DSAEK graft one day after surgery. Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.en. No changes were made. (Courtesy Stefani Karakas, CRA) |

According to the 2022 Eye Banking Statistical Report from the Eye Bank Association of America (EBAA), 15,544 DSEK, DSAEK or DLEK procedures were performed and 15,248 DMEK or DMAEK procedures were performed last year in the United States. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, 17,428 DSEK, DSAEK or DLEK procedures were performed and 13,215 DMEK or DMAEK procedures were performed. Today, PK shares a third of corneal transplantation cases along with EK procedures. In 2019, 17,409 PK procedures were performed; then in 2022, this number dropped to 15,835. The total number of corneal grafts in 2019, including PK, EK, LK and other keratoplasty procedures, was 85,601. In 2022, the total number dropped to 79,126, due to the pandemic in 2020 affecting donor populations.6

“During the pandemic, there was a dip in surgery, but that was very short-lived,” says Dr. Hannush. “The dip wasn’t because people were too busy. It’s because there wasn’t any tissue to give everyone. The Eye Bank Association of America created some very strict rules on which tissues we can be used from donors who may have had COVID, so there was less availability of donor tissue for our patients who needed it.” According to EBAA, only 66,278 corneal grafts were performed in 2020. In the United States, the usage of keratoplasty tissue dropped 20 percent due to the pandemic. Now, eye banks are recovering and usage rates in 2022 are only down by 5 percent compared to pre-COVID levels.6

Penetrating Keratoplasty

There’s still a place for PK in corneal transplantation, but nowadays it has to do with more severe cases, experts say. “It’s for patients who have full-thickness corneal opacities, full-thickness thinning or even perforation,” says Dr. Culbertson. “We do a lot of our penetrating keratoplasties to excise infections and/or seal the perforation from an infection.”

Dr. Syed adds, “When someone has an infected cornea, like corneal ulcers for example, and the ulcer is eating through their cornea and it perforates, then we do a full thickness transplant. The goal in that case is a therapeutic PK. We’re trying to cut out the infection and those are almost always full thickness transplants.”

There are times when a graft fails from a PK and a surgeon must decide whether to redo a full thickness transplant or try another method. “Doctors have a choice for patients who had previous successful penetrating keratoplasty and saw well until the graft failed,” says Dr. Hannush. “You can do an endothelial graft, DSEK or DMEK, behind the full thickness transplant, or you can simply repeat the transplant depending on your level of comfort.”

Dr. Hannush provides another example on when to employ PK. “If I feel that the stroma of the cornea is involved, not just through edema but through scarring, then I know they need the stroma to be replaced,” he says. “If I think they have endothelial dysfunction, then I know that the entire cornea needs to be replaced. For example: herpes simplex keratitis. A patient has had multiple episodes and developed scarring in the cornea. We know at the very least they need 96 percent of the anterior cornea to be replaced, but for that you only need DALK. But when I’m able to image the endothelium to discover that the endothelial cell count is very low, then I know the patient needs a full thickness transplant for visual rehabilitation. Corneal scarring will remain the main indication for penetrating keratoplasty. It will decrease over time, but it will never go away.”

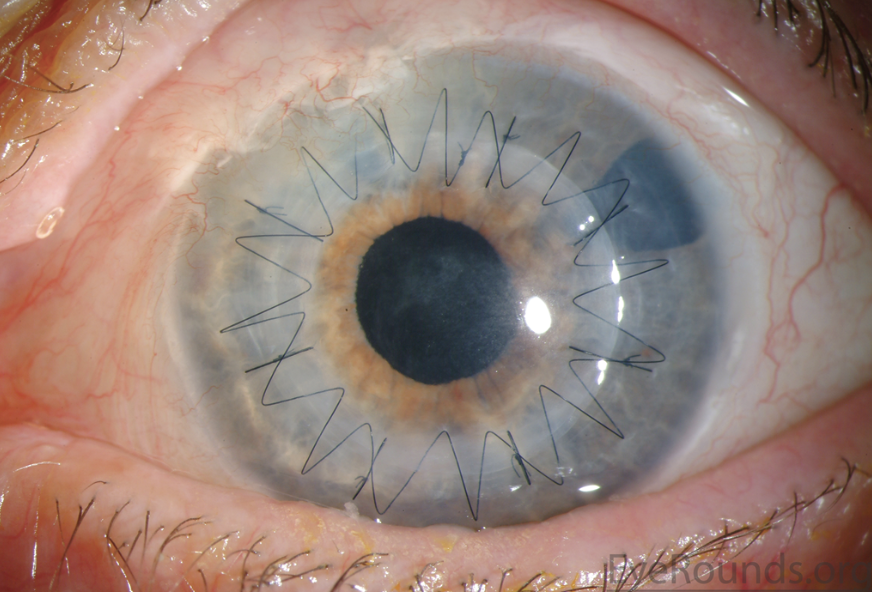

|

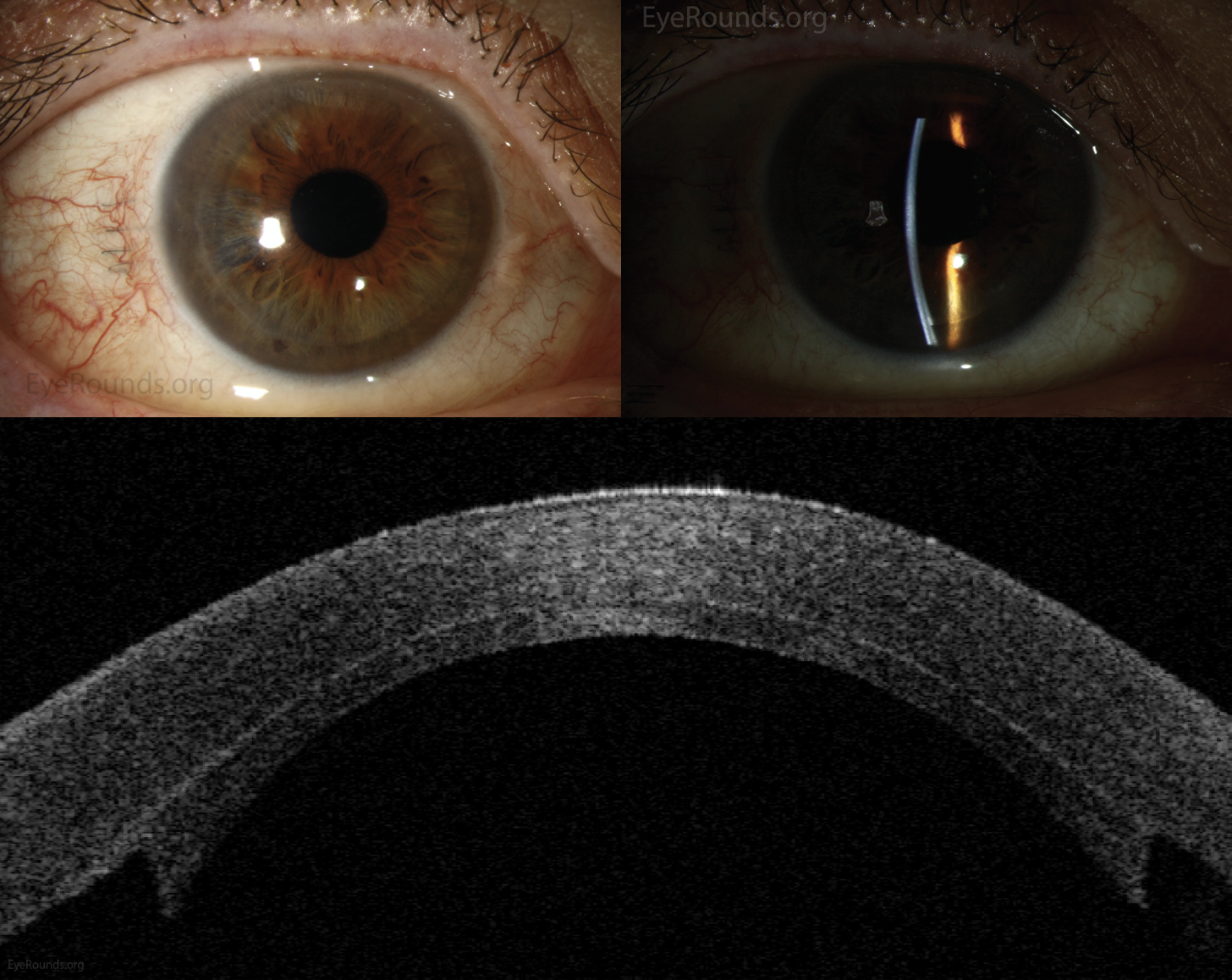

| Combination of running sutures and interrupted sutures. Ophthalmic Atlas Images by EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa are licensed under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.en. No changes were made. (Courtesy Stefani Karakas, CRA) |

Other Keratoplasties

The scope of corneal transplantation surgery doesn’t stop at PK, DSEK and DMEK. There are lamellar keratoplasty procedures and keratoprosthetics that have been developed over the years that are useful in practice. DALK is the most widely used lamellar keratoplasty.

“DALK is a procedure that replaces 96 percent of the cornea, leaving the endothelium and Descemet’s membrane behind and, usually, leaving behind the pre-Descemet’s layer, also known as Dua’s layer,” says Dr. Hannush. “The main indication for DALK is keratoconus. However, the total number of grafts done, whether they’re DALK or penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus, have decreased with the advent of scleral lenses to manage these patients and improve their vision and the approval of collagen cross-linking in the United States.”

If there’s no sign of endothelial dysfunction or dystrophy, then employing a DALK has its benefits. “DALK is terrific if one can master it because it has that great advantage of retaining one’s own corneal endothelium,” says Dr. Kenyon. “If you proceed with a DALK, you can essentially give the patient lifelong normal vision, because that tissue won’t reject to any degree of concern, whereas a penetrating keratoplasty has lifelong risks of rejection and some other significant complications and failure risks.”

There is some leeway with DALK. “Anytime we do a DALK, we have to be prepared that the DALK in our hands may not work and we will just convert it to a full-thickness corneal transplant,” says Dr. Hannush.

On the other side of the corneal transplant spectrum is the Boston Keratoprosthesis, or KPro, the most widely used artificial cornea. It’s not employed in practice as much as keratoplasty, since PK, DSEK and DMEK can restore the eye’s vision without the need for an artificial cornea. “The Boston keratoprosthesis is performed in cases where the patient is not a candidate for any of the above,” says Dr. Syed. “It is usually reserved for severely sick eyes in which any other form of corneal transplant would fail. If a patient has failed three or four transplants, then a subsequent transplant will typically do worse than the previous one. So, if I’m referred a patient who failed three PKs over their lifetime, I’m generally not putting a fourth PK in their eye. In those cases, I’ll do the Boston keratoprosthesis if the patient is a candidate.”

“A small fraction of keratoplasty procedures, about 3 to 4 percent, are procedures like anterior lamellar keratoplasty, keratoprosthesis, and other techniques,” says Dr. Culbertson. In the United States EEBA reported 476 DALK procedures in 2022, which is much lower than pre-COVID levels. In 2019, 745 DALK procedures were performed. KPro procedures across the country held steady numbers until the pandemic. In 2019, 251 KPro surgeries were performed versus 122 in 2022.6

Future of PK

Surgeons were asked if they believe PK will become obsolete in the future as the number of EK procedures continue to grow. They all showed optimism towards PK and its place in their armamentarium. Dr. Hannush stated previously that corneal scarring will remain the main indication for PK, and while cases will decrease over time, the procedure will never go away. Dr. Syed adds, “There will always be a role for penetrating keratoplasty in our field because of infections, and advanced keratoconus.”

EK procedures may decline since surgeons have exhausted the advancements of the procedures. “I think we’re getting to the point where we sort of maxed the refinement of DSEK and DMEK as compared to their original iterations,” says Dr. Culbertson. “There are improvements that can be made in technique and other things, but I think that’s kind of reached a plateau where any advancements will be minimal compared to what we have now and the results we see.”

“The reimbursement for this work is so low in America,” adds Dr. Hannush. “EK is such an undervalued procedure. For a surgeon to invest time in the procedure—when he or she could be doing cataracts—and then also have to deal with the potential complications is going to affect the growth of these procedures.”

The future advancements in keratoplasty currently look to involve less-invasive endothelial transplantation such as that pioneered by Shigeru Kinoshita, MD, in Japan, which involves the injection of a patient’s own cultured endothelial cells. “Endothelial keratoplasty may at some point become much less frequent, because cultured injected endothelial cells are on the horizon,” says Dr. Syed. “Instead of having to surgically implant them, you can inject them similar to how our retina colleagues inject patients who have macular degeneration or macular edema. This approach will theoretically replace endothelial keratoplasty if it ends up being successful.”

In 2020, Dr. Kinoshita and a team of researchers followed up on a five-year study of 11 eyes of 11 patients who underwent corneal endothelial cell injections to treat some form of endothelial failure. After five years, 10 of the 11 eyes were restored to normal corneal endothelial function.7 BCVA was improved significantly in the 10 eyes. Prior to the injections, the mean VA was 0.876 logMAR in patients, then after the injections, the mean VA was 0.046 logMAR.7 Researchers reported no major adverse reactions directly related to the endothelial injections.7

In the next decade, who knows where corneal transplantations will stand? “What we’re working on in the next 10 years won’t address corneal scarring through genetic research or cell-based therapy,” says Dr. Hannush. In the end, then, it appears PK is here to stay.

Dr. Kenyon is a consultant for Beaver-Visitec International. Dr. Syed is a consultant for BioTissue. Drs. Hannush and Culbertson have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Gurnani B, Kaur K. Penetrating keratoplasty. StatPearls 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592388/.

2. Moshirfar M, Thomas AC, Ronquillo Y. Corneal endothelial transplantation. StatPearls 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562265/.

3. Fernandez MM, Afshari NA. Endothelial keratoplasty: From DLEK to DMEK. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2010;17:1:5-8.

4. Tourabaly M, Chetrit Y, Provost J, Georgeon C, Kallel S, Temstet C, Bouheraoua N, Borderie V. Influence of graft thickness and regularity on vision recovery after endothelial keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:9:1317-1323.

5. Woo JH, Ang M, Htoon HM, Tan D. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;207:288-303.

6. 2022 Eye banking statistical report. Eye Bank Association of America; 2023.

7. Numa K, Imai K, Ueno M, Kitazawa K, Tanaka H, Bush JD, Teramukai S, Okumura N, Koizumi N, Hamuro J, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S. Five-year follow-up of first 11 patients undergoing injection of cultured corneal endothelial cells for corneal endothelial failure. Ophthalmology 2021;128:4:504-514.